Artist Dustin Yellin reflects on the parallels of his new glass works with China's terra cotta army

Dustin Yellin has long rejected the traditional parameters of artistic education and development. Departing high school without troubling with graduation, he spent a year with a physics professor, enjoying the rigor of scientific methods, which he would later employ in his art. His works are momentous in scale and ideas, mirrored by Pioneer Works in Red Hook, Brooklyn, the 24,000ft warehouse space which he bought in 2011 and repurposed as a thoroughly modern mélange of exhibition space, education centre, science lab, observatory, studio, mental and physical playground and party venue.

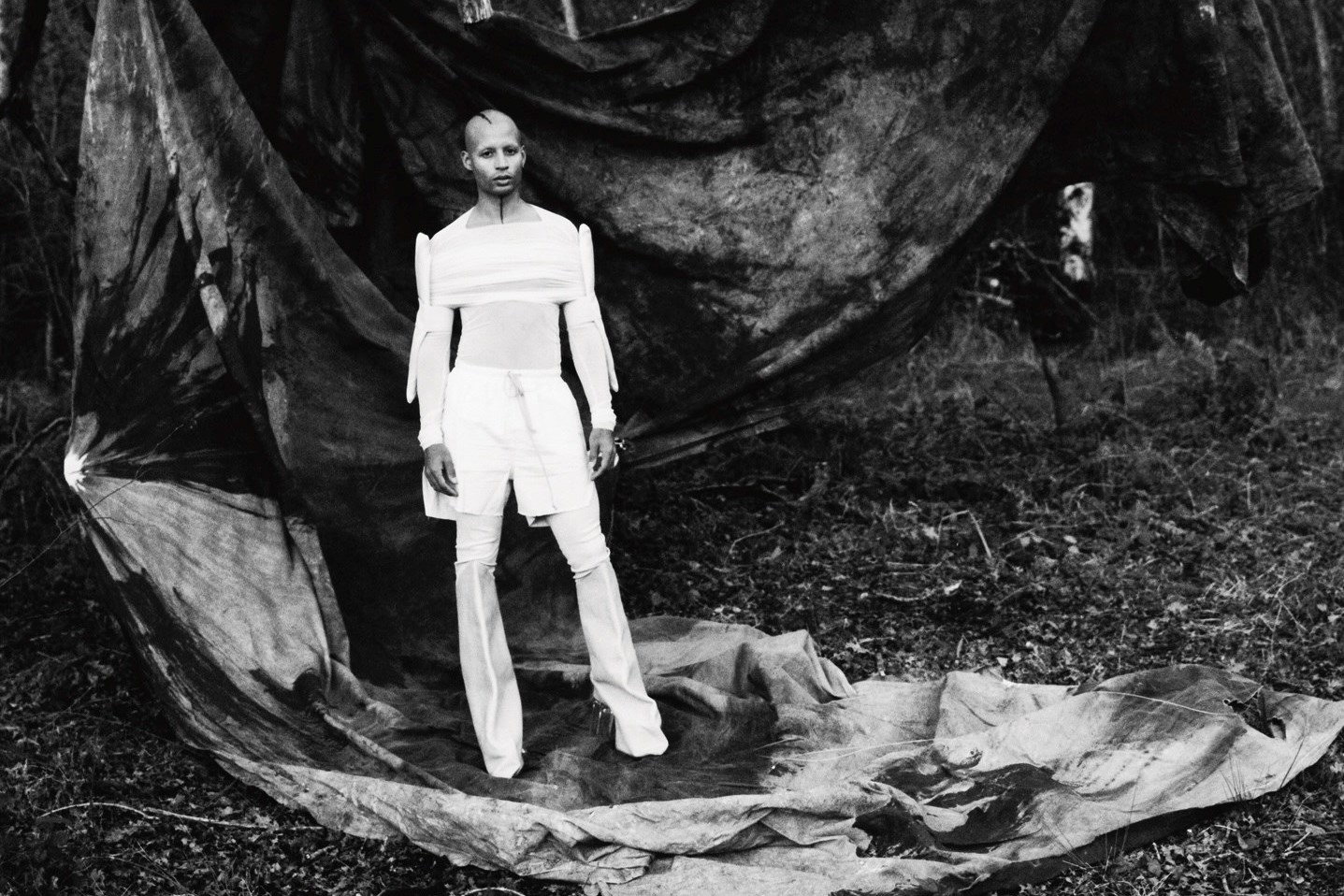

Yellin’s work is varied and vivid. Starting first with oil on canvas, he has experimented with many mediums, his works growing and expanding in the real world in correlation with the concepts he aims to portray. The Triptych, an epic 12 ton amalgam of glass, paper and acrylic, took a year to make, and portrays the artist’s multifaceted view of the world and the universe, seething with unknowable forces, “overflowing with joy and disaster”, and his new works are on a similar – if more fragmented – scale. Derek Peck visited Pioneer Works in New York for a glimpse at the work in progress, and to ask Yellin why, for him, bigger is often truly better.

"I'm concerned with the way consciousness forms and arrests itself" — Dustin Yellin

While visiting your studio recently I got a glimpse of a new piece you're currently working on that you referred to as the "terra cotta warriors" (after China's famed 3rd Century B.C. sculptures). Obviously you work in glass, not terra cotta, so the reference is more thematic and contextual. How do your 21st Century sculptures differ in terms of what you’re expressing through them?

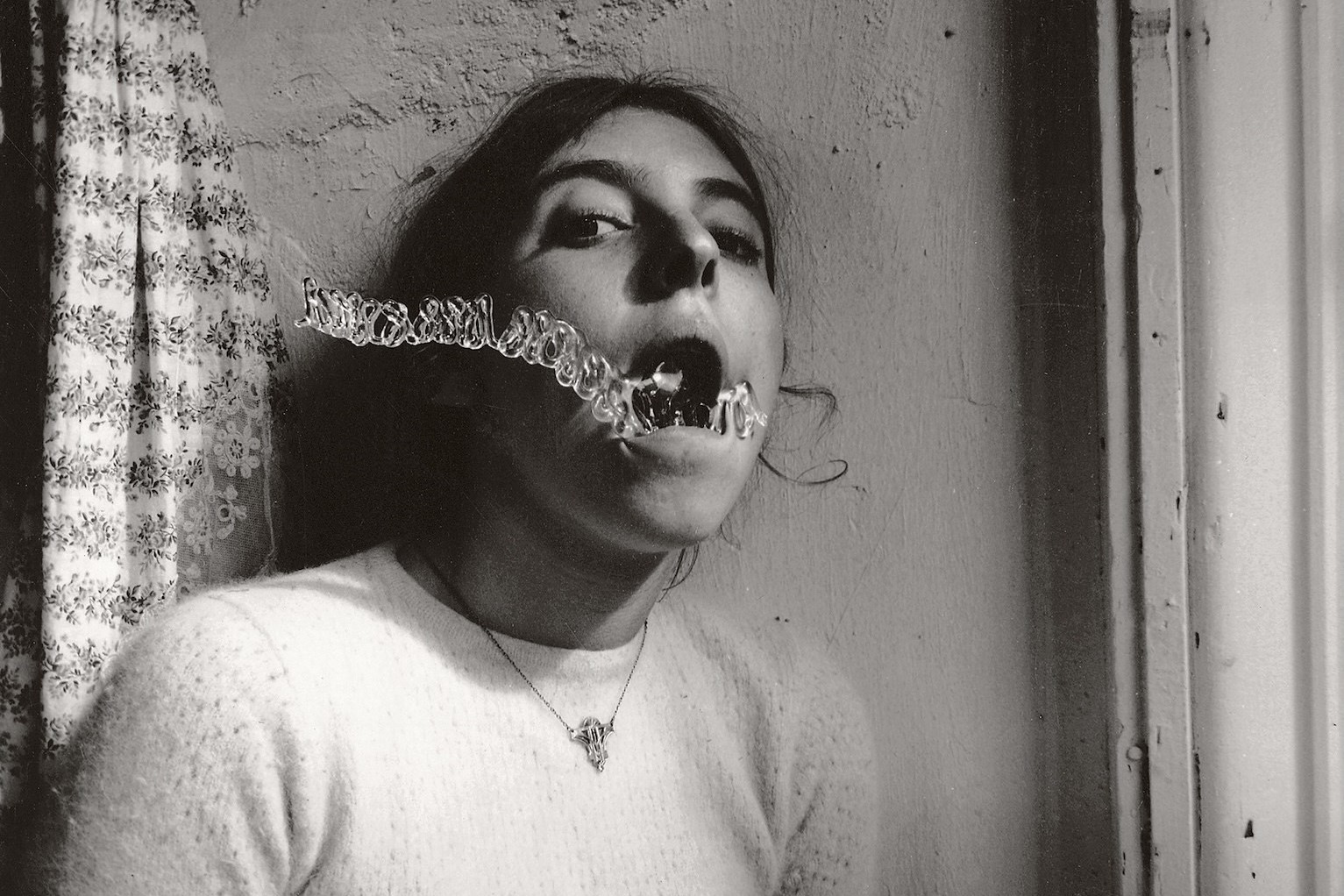

I've referred to the pieces as "psychogeographies". I'm concerned with the way consciousness forms and arrests itself. These figures dramatise and literally encase, freeze, and hold, in a mesmerised abeyance, this cultural process. In that way they're definitely, and explicitly, 21st century forms, with nods to certain continental theories. However I don't want to foray completely into a sociological explanation of the self nor link the cultural production of art to it, which, also, is so vastly different from 3rd Century BC Chinese procedures, but in some sense, I do think we owe our "selfhood" to various artistic mechanisms, the collage, the ludic and aleatory dance of many moving parts, the recombination of snatches of popular music, philosophy, reproduced images, texts, that comprise the thoughts of our waking and sleeping subjectivities.

You said you plan to make 500 over the next two to three years, which is genuinely monumental. What inspired you to want to make a piece of this scale?

I'm inspired by ambitious and social work in the Beuysian sense of the social and ambitious. At this scale, it's interesting to see how the many communicates through the infinitesimal. I mean by this, the play between the nearly molecular in size cutting that compose and shape and also shift with the larger forms. If I get 100 of them (because 500 may be unrealistic), those hundred humans will be one work. I see them as one piece – as a play between the grand and the tiny. I never see them as singularities. They are these sort of 3,000-pound microscope slides that will make road maps to our culture and its development, to our children’s children.

This is also a massive undertaking that requires a near absurd amount of dedication. I always have to stop and ask myself, "what if I feel like doing something different?" I’m open to the constant influx of new ideas and projects refocusing my attention, and going with what I have to do at that specific moment. If I create 500 or 100, or some number between, then I’ll have done what I needed to do, specific to that work and what inspired it.

Text by Derek Peck