New York photographer Josef Birdman Astor is known among his peers as a “photographer’s photographer”. His work is revered for its technical mastery, ultimately made invisible by a beautiful use of light, shape, and concept. With the premiere last

New York photographer Josef Birdman Astor is known among his peers as a “photographer’s photographer”. His work is revered for its technical mastery, ultimately made invisible by a beautiful use of light, shape, and concept. With the premiere last week of his first film – a documentary titled Lost Bohemia – he is now, too, an artist’s artist. For years, Astor was a resident of the Carnegie Hall Artist Studios, inhabiting one of only a handful of skylight residences atop the legendary music hall (160 studios were commissioned by Andrew Carnegie shortly after the hall was built to help foster the arts in America and New York City). For over 100 years, they have given innumerable artists and students an opportunity live, explore, study, and create – and they added immeasurably to the cultural heritage of the city in which they existed. Throughout the 20th century, some of America’s most important artists either lived, worked, or studied in the studios: Mark Twain, Marlon Brando, Isadora Duncan, Grace Kelly, Leonard Bernstein, Martha Graham, George Balanchine, James Dean, and from the 80s onward a number of well-known contemporary actors studied there including Michael Douglas, Denzel Washington, Mira Sorvino, and John Turturro. Now the two towers are being gutted and many 19th century staircases, skylights, and other architectural jewels will be destroyed to make way for new corporate offices, music classrooms, and a private rooftop terrace for trustees and donors of the Carnegie Hall Corporation.

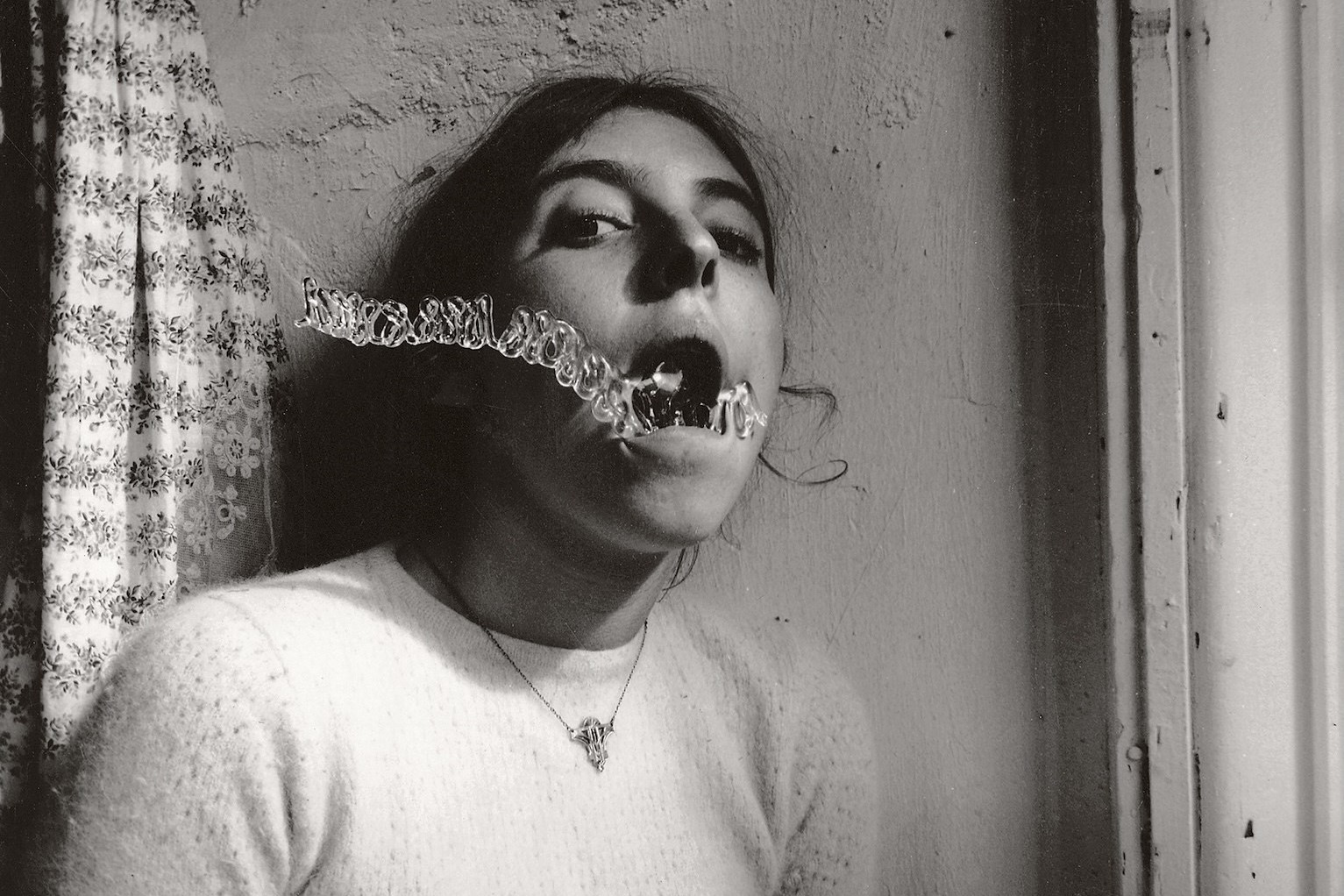

Inspired by his neighbors, some of whom had lived in the studios for decades, Astor began photographing and filming the great diversity of artists who lived and worked beside him. When, in 2007, everyone was served with eviction notices by the city of New York under the auspices of the Carnegie Hall Corporation, his footage took on new meaning as an emotional chronicle of the artists’ efforts to resist eviction, and, ultimately, their defeat.

As with the East Village, The Bowery, The Chelsea Hotel, and a dozen other bastions of Manhattan artistic life, the sad story of contemporary New York continues....

Derek Peck: When did you move into the Carnegie Studios?

Josef Astor: It was 1985. Very few Carnegie Studios were rented after that time.

Derek Peck: How did you find out about them, and how were you able to get one?

Josef Astor: Like everyone in 1985, I was hanging out in the East Village at the Pyramid Club, and heard about an available studio above Carnegie Hall. Despite my nascent career being unable to manage the overhead, the advice of friends was: you must take it! Fortunately, I took their advice. I eventually asked that same question of all the tenants I met there: How did you get your Carnegie Studio? And it was always a version of the same response: “The place found me.”

Derek Peck: We’re they free or just subsidized?

Josef Astor: Neither, and that's a misconception that needs to be clarified. I've read some blogs written by those who believed the artists had a sweet deal, so were blinded by New York 'real-estate envy' and unable to see the real issue at hand. But there were three categories of tenancies – commercial, residential, and rent control. Most of the tenants paid market rate commercial rents, only a handful were rent controlled. One purpose of the studios was to support the concert hall; but Carnegie Hall in recent and more solvent times looked at the artists’ colony as a burden, and wanted the studio space for the operations of the Carnegie Hall Corporation. So the rents were increased beyond what an artist could afford.

Derek Peck: What was going on in your career at the time?

Josef Astor: Not much. I was just starting out as a photographer and had done some small photos for Vanity Fair, but was not financially stable, so taking on the studio was a gamble, but eventually turned into the jump-start that I needed.

Derek Peck: What effect did having such a place have on your life and art?

Josef Astor: I was living in a secret, hidden world, which soon became a real home to me, which was a blessing considering the nasty midtown neighborhood below. My friends from the East Village never migrated to midtown, so I had no alternative than to be reclusive and work in my new studio. Living among the other artists was always a comfort and an inspiration, even if it was simply about knowing they were there. The momentum my work took after moving there was a direct result of the unique qualities of the studio, and the environment around it. The studio with its northern skylight provided the setting for a theatrically staged style that I developed in that space. I often wonder had I not gone to the Pyramid Club that night in 1985, would I be making a different sort of pictures?

Derek Peck: Who were your nearest neighbors and tell us a little about them?

Josef Astor: To reach my 8th floor studio, you would take the elevator to the 6th floor (because there is no "8" in the elevator ) exit on 6, and walk up a small set of steps, and you were inexplicably on the 8th floor – very typical of the labyrinth of the Carnegie Studios. The 8th floor was unique in that the studios sat on the roof directly above the concert hall – they had soaring ceilings and beautiful north-facing skylights. Across from my studio there was a trap door in the floor and if the workmen left it unlocked, I could sneak down inside the ceiling of the main hall among the dusty old pipes and hear the concerts — it was a very Phantom of the Opera experience.

Just down the hall from my studio on the 8th floor was the massive pipe organ studio occupied since the 1930s by Emilia Del Terzo, who taught piano and organ, and used to play it in her peach-coloured robe. A turning point in the film is the demise of that grand organ studio. The Neubert Ballet occupied several large studios on the 8th floor; the little tutus and buttercups were always darting around the 8th floor hallways. At the other end of the hall were two acting schools – Wynn Handman and Robert X Modica – both very respected teachers. The students in Mr Modica's room could be heard screaming at all hours of the night, working on their method techniques.

When I first moved in, Ruth Gordon and Garson Kanin had the studio just next to mine. Bobby Short had lived in my studio for a while, and Ballet Arts (once the most famous dance studio in the city – Isadora Duncan, Agnes de Mille, Balanchine) was a few doors down the hall. Many of the legends of the studios had faded away by the time I moved in, so instead of regretting that I missed the heyday I began documenting what remained, to try and preserve what was left of its original ambience.

Derek Peck: Was there anyone living in the building at the time that you felt particularly inspired by, or that you considered a major artist?

Josef Astor: That would have to be concert pianist Donald Shirley, and the poet Elizabeth Sargent, who became real friends and provided constant inspiration and still do to this day. Donald Shirley was one of the first black concert pianists – he enlightened me with the story of how he was denied the concert career he trained his whole life for because Columbia Artists told him the world could not accept a black concert pianist. But he finally got there by going ‘though the back doors of the nightclubs’ and eventually playing numerous dates in the main hall of Carnegie Hall. He once said: ‘I like playing downstairs, because I can just run up here to my studio afterward, sit in my bathtub and drink champagne.’

Elizabeth Sargent is the real thing, a poet who lives as a poet 24 hours a day. She's a recluse who keeps unusual hours, and was rarely seen around the building. She would leave multiple messages every day on my answering service, beginning at 5:00 am – advice on art, love, life and how to structure the film I was making about the Carnegie Studios; she wrote a history passage that's included in it.

Derek Peck: What happened when you received official word that the Hall’s board was evicting everyone? And how long after did you start to organize yourselves for a fight?

Josef Astor: We all sensed right away that it was an ‘all-or-nothing battle’, not just to save our studio spaces, but the entire place. There were some evictions in the past, but this time it felt final. Nonetheless, we were naively confident that we could win. We organised quickly, but not very efficiently. We were an eclectic group of artists and artist-adjacent businesses, and keeping them cohesive was very difficult. In hindsight, I'm glad we didn't know then what we know now, meaning the actual scale of the Goliath we were up against. So we did the maximum we knew how, figuring things out as we went along – we wrote letters, met with City and State politicians, went to Albany, staged a rally outside City Hall lead by former Modica student John Turturro, made t-shirts, pamphlets....

Derek Peck: When did you decide to make a documentary about what was happening?

Josef Astor: I never intended to make a documentary about the evictions of the artists in the Carnegie Studios. I began documenting the tenants in 2001, six years before we were given lease termination notices. So when the notices appeared on all the studio doors my camera was already poised, and the tenants accustomed to seeing me with it. This was how I was able to capture the subsequent drama as it unfolded, with an immediacy and a verité spirit. Sometimes the tensions were so high that I forgot the camera was on – it was all filmed in the real heat of the moment.

Derek Peck: Besides the film’s obvious value as a chronicle of the evictions, it must have been an extremely emotional process for you — not only being evicted yourself but getting inside the stories of all the resident artists that were forced out.

Josef Astor: Yes, there was considerable stress, as I was wearing three hats – tenant organiser, filmmaker, and victim of the evictions. The tenants became closer knit as a result of this fight and recognised what was at stake was not only our spaces and the community there, but the tradition of the studios themselves. I found enormous inspiration from the older tenants who bolstered our confidence with tales of fighting the CHC in the 1970s. In particular Jeanne Beauvais, the chanteuse in studio 858, really stands out as someone who continued her fighting spirit up until the bitter end – she eventually passed away during the filming. She was instrumental in saving the entire Carnegie building when it was threatened with demolition in the late 1950s.

Derek Peck: I read that Elizabeth Sargent, the last artist tenant holding out, left in August. Does that mean that it’s over at this point?

Josef Astor: No artists or tenants remain. The studio towers are undergoing a mass-demolition – so yes, the great tradition of the Carnegie Studios is most sincerely dead. The last tenant to sleep there was the poet Elizabeth Sargent; the last tenant to move out was Editta ‘The Dutchess of Carnegie Hall’ Sherman. I was in Editta's studio on her last day having a final toast with Donald Shirley, Christine Neubert and Elizabeth Sargent, and it was truly sad. Editta was the figurehead of the place, who had always insisted she would be there at age 100 (two more years) and that they would have to carry her out.

Derek Peck: What has happened to the artists since?

Josef Astor: Each has a different story. Some just closed up shop, others found alternative spaces, many are still in limbo. The rent control tenants have all relocated to high-rise apartment towers nearby. Quite a severe shift in lifestyle from the minimal domestic comforts they had in the Carnegie Studios. But the amenities in their new high-rises are meaningless to them; their community is gone. Editta Sherman was a resident in the Carnegie studios since 1949 and misses it terribly.

Derek Peck: What strikes me is this wasn’t a major corporation making this decision; it was the city of New York, who owns the buildings.

Josef Astor: I wish more people understood that. New York City owns the building and is the landlord. Carnegie Hall Corporation is the tenant. We were subtenants and our existence was meant to be secured by a Charter written in 1960 stating that the balance of studios must be preserved and continue as originally intended. The lease between the Carnegie Hall Corporation and the City of New York was to remain in effect for 100 years.

What also must be factored in is this: we are living in corporate real estate-friendly times that are not conducive to preserving these types of artists colonies. The Mayor, if he had chosen, could have saved the Carnegie Studios with one gesture.

Sanford Weill is the Chairman of the board of trustees of the Carnegie Hall Corporation.

The son-in-law of Mr Weill was chosen as the architect of the renovations. The Landmarks Preservation Commissioners approved the renovation plans to destroy the rooftop skylights, and gut the interior. Carnegie Hall Corporation hired a ‘historian’ to convince the commissioners the skylights were not original, and Mr Carnegie actually wanted a roof garden instead of artist studios.

Derek Peck: I lived for several years in Paris, and somehow I can’t imagine this happening there — or even in London or Rome. What does this say about America and the value we place on art, artists, and cultural patrimony in our society?

Josef Astor: I am very curious to see how the film will play in Europe, knowing how they love to characterise Americans as Philistines who destroy their own cultural history, only concerned with a short-sighted view of the present. I hope Lost Bohemia will preserve some of the history of these very unique studios, and capture the intangible atmosphere that surrounded them. But I also hope it will serve as a cautionary tale of how fragile our cultural history is and how much of the soul of the city is due to the artists who live and work in it.

Lost Bohemia had its world premier on November 5 at the DOC NYC Film Festival where it won a Special Jury Prize.