AnOther explores the first London solo exhibit of Snow's provocative oeuvre, comprised of rare Polaroids, collages, prints and sculptures

Dash Snow was part of a wealthy art collector dynasty. His grandfather was a Buddhist scholar and Uma Thurman was his aunt. He was rebellious from a young age, but no institution could iron him out. For a time, he was a member of the notorious Irak graffiti crew, he pasted his artworks with semen and made an installation of his own urine. When he died in 2009, from a drug overdose at a hotel in Lower Manhattan, aged just 27, he left a young daughter behind.

There's been a lot of salacious writing detailing Snow's hedonistic life – but it’s most vividly experienced in his own visual works, collages and installations of “situations”, as well as the Polaroids he took of himself and his friends ejaculating, injecting, menstruating, laughing, drinking, defecating. It was a personal document of the stuff he might not remember as he saw it, and it became a raw portrait of the complex notion of American freedom.

Snow didn't receive much attention in Europe, with only one major exhibit at MACRO, Rome – until now. This month, seven years after his death, his work will be shown in Hackney for the first time in Hello, This is Dash. Gallery owner and curator Annka Kultys explains the impetus behind the show: “I love Dash Snow’s work, and I had this show in mind for years – I had already included his work in one of my exhibitions in Paris in 2012, at my previous gallery. Now, I am showing his work because I believe that his works are a bridge between his generation and the new Instagramming generation who also makes the private public. Making art by recording his life was a form of both communication and catharsis for Snow.”

Snow’s compulsive way of photographing was partly a way of coping with anxiety and paranoia. Looking at the pictures now, after his death, it seems obvious that his photography, and the things he photographed, were dangerous to him. Snow was concerned about surveillance and hated the police. He shunned the Internet and phones. There's vulnerability and sensitivity in his images – motifs of skulls, darkness, drugs, penises and blood create a nagging sense of mortality. Dash knew it wouldn’t all last, and he was desperate to hold on to the moment as it disappeared.

During his lifetime, many critics ridiculed Snow’s work because of his subject matter and his quick, prolific, largely spontaneous way of working. His message is often pushy, direct, or vapid. Looking at some of the works now, at a time when we’re drowning in photographic representations, it is true to say that they could appear as somewhat clichéd portraits of disaffected youth. But they do continue, in some way, the legacy of American photographers such as Walt Whitman and Walker Evans, not discriminating with the camera between interest and trivia, because life is full of trivial things, as much as it is made up of beauty, and ugliness. (Sontag describes this as a “Whitmanesque imperative”).

An example of this is the iconic Hell, (2005), that appears twice in the London exhibition. It depicts the forecourt of a Shell petrol station at night – the illuminated sign missing an ‘S’. The political comment on corporate America and the defunct American dream is obvious. But as John Brennan writes in a catalogue essay that accompanies the show, all of Snow’s momentary glimpses are random and limited – as a photograph always is.

![Dash_Snow_002_Dream_Dust_(46x58.5cm)[2005]_web](https://images-prod.anothermag.com/604/azure/another-prod/350/3/353500.jpg)

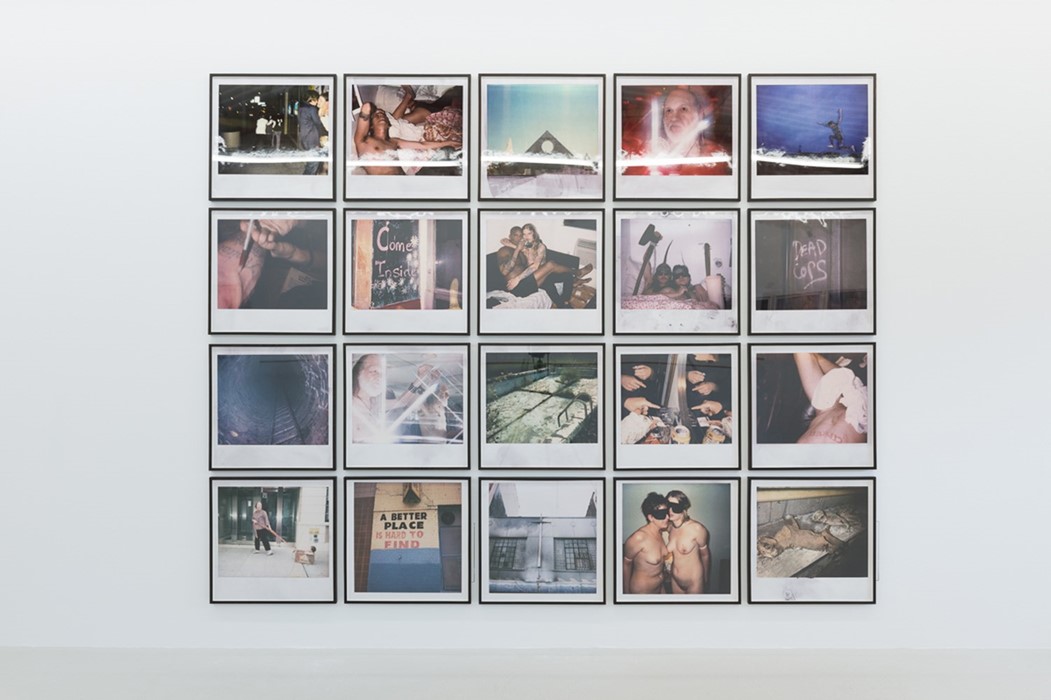

Among the notable works is Polaroid Wall, (2005) an arrangement of 20 of Snow's Polaroids blown-up large – aesthetically it prefigures Instagram. “Come Inside” – reads a sign snapped in one Polaroid. “There is No Better Place Than This.” Presented as art, the images expose the artist’s inner world and invite viewers to participate in it too.

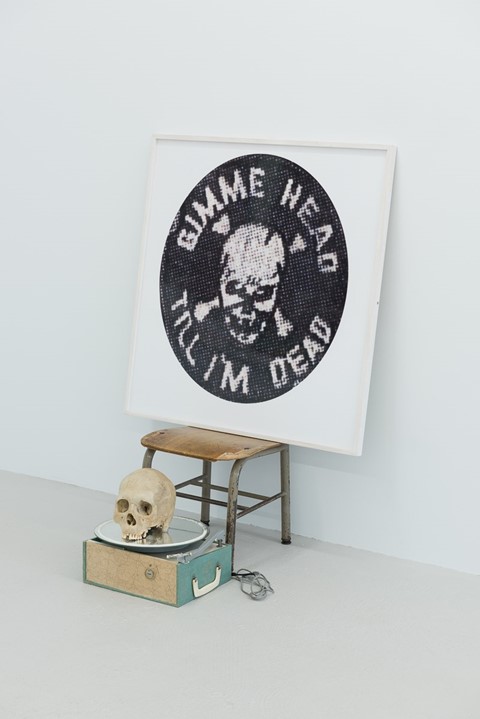

As well as grappling with the directness of Snow’s politics (Saddam Dick, 2007, one example) Hello, This is Dash, brings up some of the other media Dash made. There is a collage work, Dream Dust, (2006), a neatly clipped and pasted piece. The composition is occult-like, centred around a trefoil and a bag of ‘Dream Dust’ – presumably heroin.

Inevitably, there’s a feeling of alienation looking at Snow’s work today. It’s a personal view of a personal world that we, standing here looking at the work today, are detached from. In their muteness, they transmit an uncanny energy. As Diane Arbus once said: “A photograph is a secret about a secret. The more it tells you the less you know”.

'Hello, This is Dash' is on view at Anna Kultys Gallery until April 16, 2016