Edward Barber's new exhibition at London's Imperial War Museum is a poignant reminder of the persuasive power of protest

Political demonstrations are powerful things – and never more so than at moments when the global population finds itself poised on the precipice of change. Few agree more vigorously than photographer Edward Barber. In the 1980s, he set about capturing the anti-nuclear protests which were sweeping the nation at the time, and the result is a body of work which will reinforce your belief in the collective influence of humanity. He originally started the project through a collaboration with photomontage artist Peter Kennard, he explains, who he met in the late 1970s when he was working as part of photographic collective, Camerawork. “A lot of my friends at the time were peace activists,” Barber states. “Taking documentary photographs as a freelancer was my contribution – my personal form of activism.”

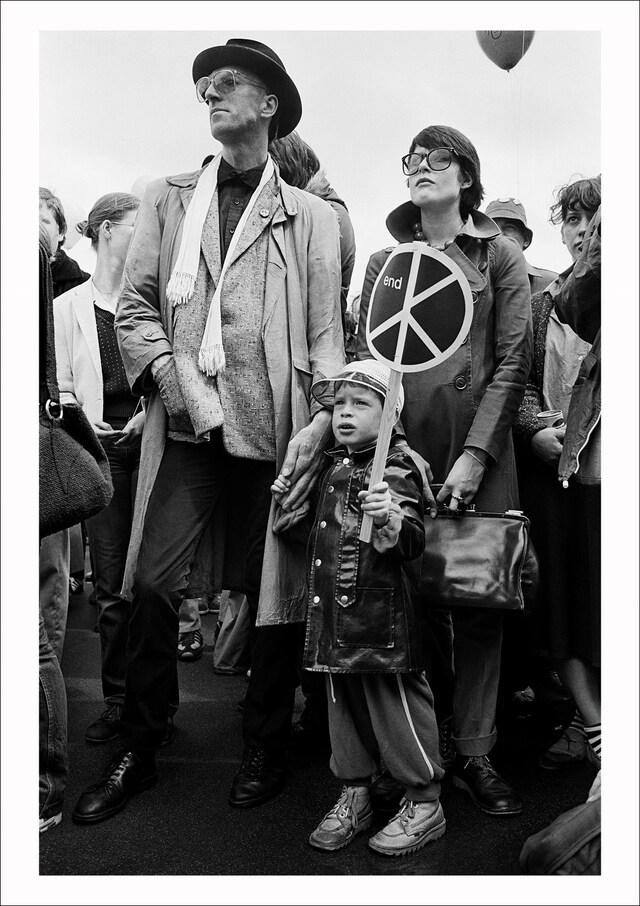

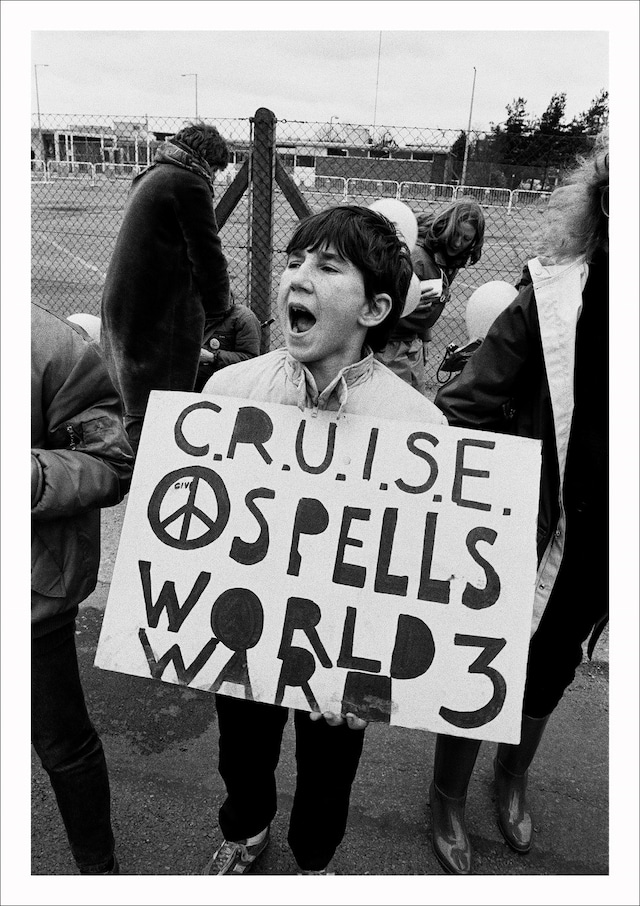

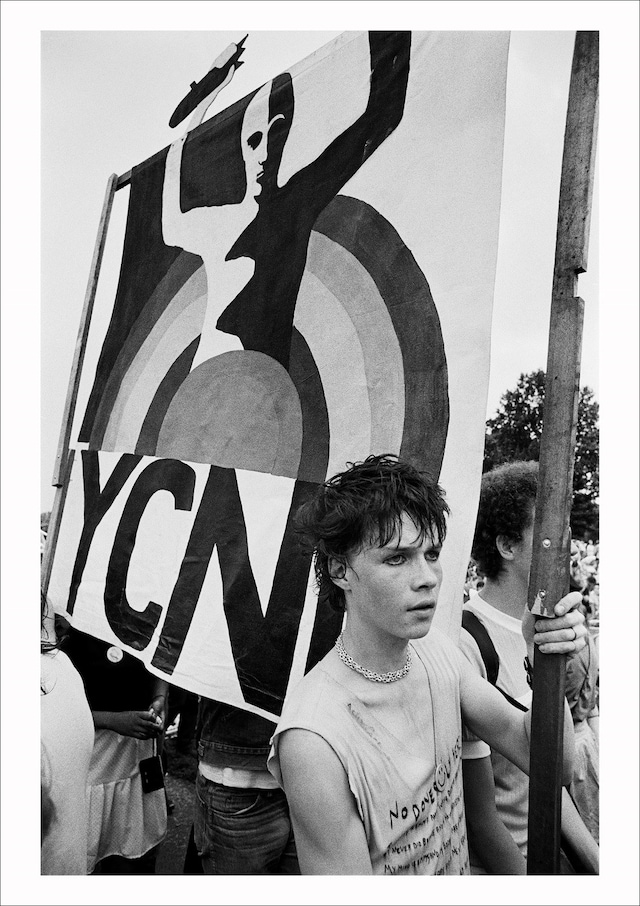

Thought not without its technical challenges, the experience provided the young practitioner with an impressive training run – and helped him to recognise his own formal preferences. “Back then, as a young freelancer, I was unused to working on the street, in fast moving situations or photographing at large public rallies and demonstrations. This project posed some real challenges for me – up until then my work was almost entirely formal portraiture, often staged and shot inside homes and workplaces. I was determined to record some of the often overlooked elements of performance, folk art and fashion in the Peace Movement. So I ended up using a combination of reportage photographs alongside the formal portraits. In fact, more than half the pictures in Peace Signs are portraits. Looking back I'm still proud of the results.”

Though powerful enough when they were first created to secure a home in a number of national publications – The Guardian, The Observer Magazine, NME and US News & World Report being just a few, not to mention the dedicated 1984 book Peace Moves: Nuclear Protest in the 1980s – the photographs are just as relevant to a contemporary context as they were 30 years ago. This month, they will go on show once more at London’s Imperial War Museum, alongside an installation created especially for the show, entitled Mind Map of Anti-Nuclear Protest. “It's an assemblage of nearly 200 separate elements created specifically for the Peace Signs installation at IWM – a large-scale hand-rendered wall graphic that provides context and explanation for my photographs,” Barber says. “The central spine traces the initial evolution of the nuclear threat before laying out the sequence of events which occurred during the 1980s.”

Unsurprisingly, it makes for a fascinating and empowering collection, prompting a wider debate about the changing role of political protest in the late 20th and early 21st century. We spoke to the photographer behind the series to find out more.

On the extraordinary interactions which occurred throughout the protests…

“When different realities collided the results were often extraordinary. There is one shot of a police officer, for example, ostensibly posing for a portrait, who seems entirely unaware that a protester has decided to blockade his police van during a demonstration outside the High Court, London, May 1982.

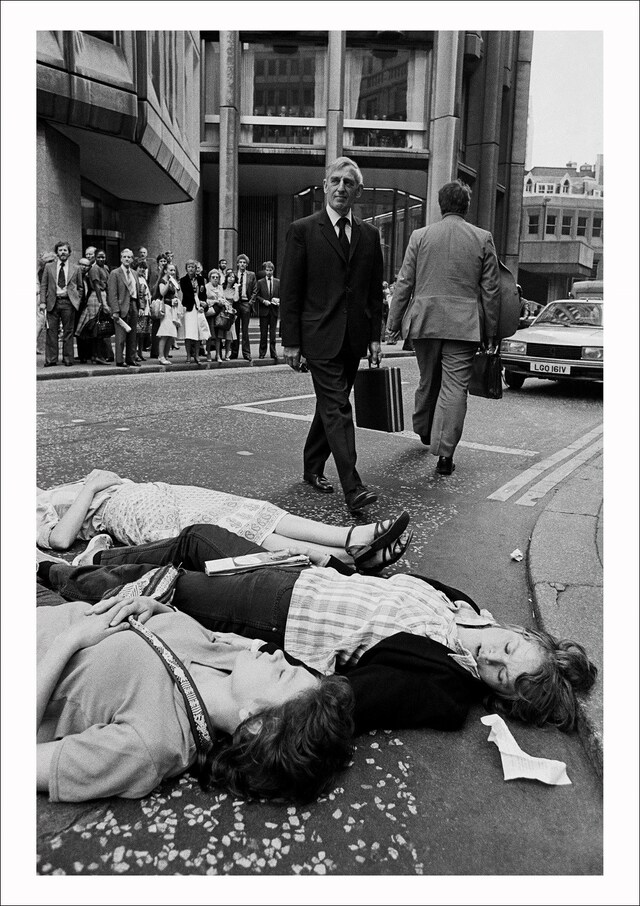

In June 1982, U.S. President Ronald Reagan was arriving in Britain. This was the first major London event initiated by the Greenham Common women, and it coincided with Falklands conflict. Greenham Common protesters staged a Die-in during the early morning rush hour in the City of London. It symbolised the one million, it was argued, who would die in a nuclear attack on London. Here (below) you see the seemingly unfazed suited City workers going about their business, determined to ignore the protesters lying in the road. Crowds of spectators gathered. Traffic came to a complete standstill in all directions. The protesters blocked all the roads outside the Stock Exchange, the Bank of England and Mansion House. After a while the police arrived, apparently unsure initially how do deal with this carefully staged protest performance.”

On his most memorable exchanges…

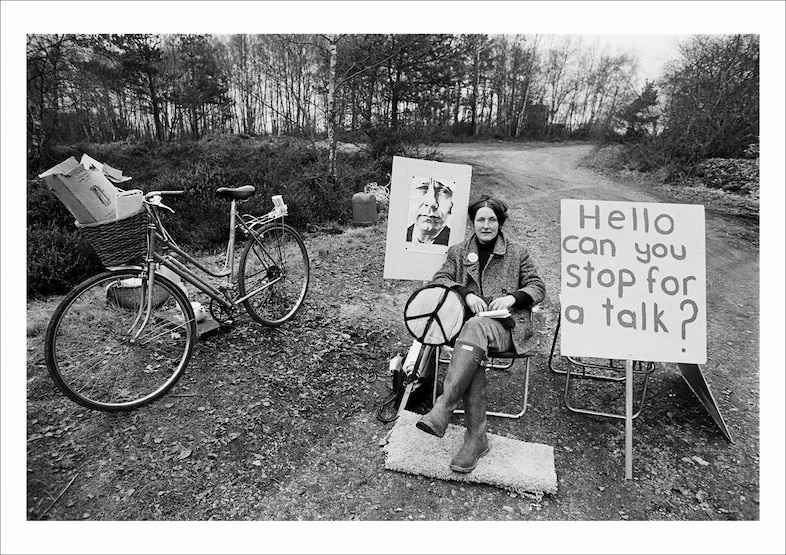

“At the larger rallies, marches and demonstrations it was often quite difficult to stop and talk. When there was a direct action taking place my primary focus was on trying to extract a useful picture from an unpredictable and often chaotic situation. I'm really a portrait photographer at heart so I was always looking for opportunities to make meaningful portraits of the protesters. This 'environmental' portrait of a woman picketing the access road to the missile silo construction site at RAF/USAF Greenham Common, February 1982, was a visual ‘gift’. It's as if the styling and art direction had already been done – the elements of everyday domestic life and camping equipment combine brilliantly with the hand rendered signs and the photocopied portrait of one of the USAF pilots involved in dropping the atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

Some of the protesters were very happy to talk and collaborate in staging photographs, like this portrait of a woman on Westminster Bridge [below], set up with the symbolic backdrop of Parliament after a group from the Women's Peace Camp at RAF/USAF Greenham Common had been demonstrating and keening (wailing in grief) in Parliament Square, London, January 1982.”

On photography as activism…

“I was young and idealistic. I wanted to use my photographs of these anti-nuclear protests of the 1980s to establish the Peace Movement as part of Britain's visible history – to document the scale of the protests, the direct actions and peace camps, to reflect the wide range of people involved and to record the artworks and visual responses. My mission was to document, celebrate and warn. I saw this as preventative photography, which included preventing the Peace Movement disappearing from the history books, as well as the hope that by disseminating these pictures I would somehow motivate people to get involved and protest against these weapons of mass destruction.”

On the changing attitudes towards political demonstration…

“These were all peaceful, non-violent direct actions. At the time, the police were often unprepared and ill-equipped to deal with the protests. There was a lot of almost 'light touch' policing. Unlike what we were about to witness during the Miners' Strike a few years later, and what we have seen more recently with the anti-Iraq War demonstrations and the Occupy protests. Our police now look and act like a paramilitary force. Sadly, ordinary members of the public seem to have been effectively put off exercising their right to peaceful protest.

For photographers working on the street today, the environment has changed completely – the ubiquity of camera phones means that virtually anybody can be a citizen journalist, which in some ways is fantastic. But serious documentary photographers now have to work even harder to make images that have a power and resonance and markedly different qualities to the vast numbers of pictures generated daily by ordinary people with phones.”

Edward Barber runs from May 26 until September 4, 2016, at the Imperial War Museum, London.