The Met Breuer's revelatory new show brings some of the seminal image-maker's earliest unseen work to light – and it's not to be missed

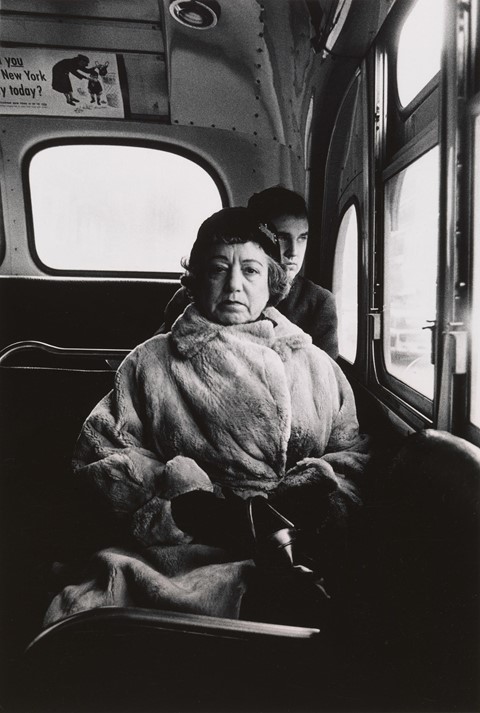

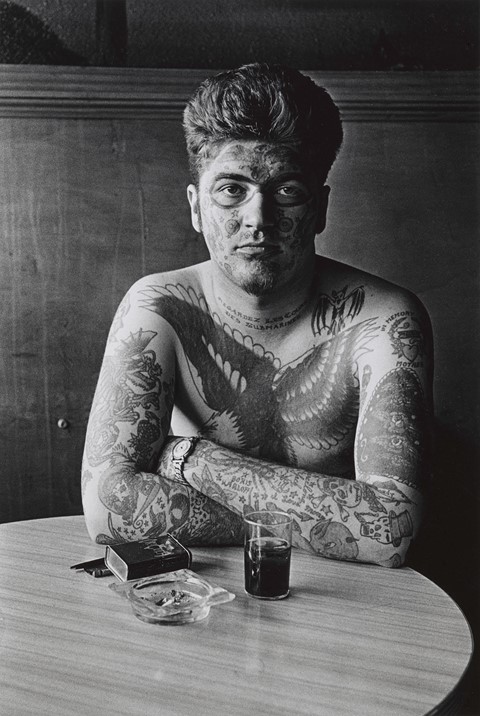

By the time Diane Arbus took her own life in 1971, aged 48, she had changed photography indelibly. In the 15 years that she was active, her raw portraits of society’s rejected, dejected and debilitated – her “freaks” of New York – were deeply disquieting to some viewers and remarkably humanist for others, making her one of the best-known photographers of the second half of the 20th century. Arbus was known not only for her persistent subject matter and style, but for the close personal relationships she established with her models, many of whom she returned to photograph again over the years.

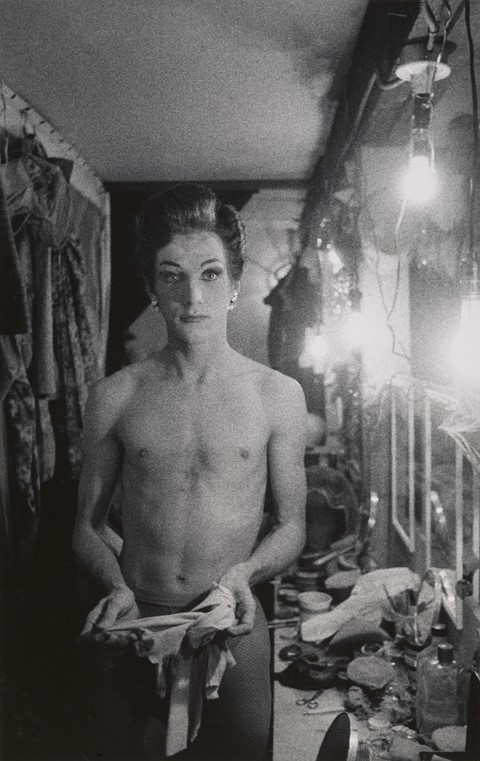

Arbus’ work stirred strong reactions in both critics and the public alike. According to one well-known account, a visitor at the MoMA spat on her photograph A Young Man in Curlers At Home on West 20th Street, NYC (1966). For some critics, the way Arbus showed society’s most marginalised was an empathetic impulse – as the photographer herself said, “the camera is cruel, so I try to be as good as I can to make things even”. Yet for others – such as Susan Sontag, who wrote extensively on Arbus after her death in her 1977 book of essays On Photography – her photographs seem to want to numb our reactions to the horror of being human, and lead to an alienation when looking. Can photographs change our perception of the world, or help us to accept what we fear? This questioning is at the core of Arbus’ powerful oeuvre, part of an ongoing personal struggle with her own position, as an American woman, as a photographer, and as a spectator.

In the late 1950s and into the early 1960s, Arbus worked as an art director alongside her husband Allan Arbus, and later as a fashion photographer, publishing work in Vogue, Glamour and Harper’s Bazaar. She later quit the fashion industry and studied under Lisette Model, teaching at Parsons School of Design and RISD in Rhode Island. Her inclusion in John Szarkowski’s pivotal 1967 group show on documentary photographers, New Documents, confirmed her place in the history of photography, making her part of a new generation of photojournalists who challenged the role of the photograph and the way we see.

This summer, a major exhibit at New York’s Met Breuer is set to reveal even more about the enigmatic photographer and her development as an artist. From July 12, a collection of more than 100 photographs from a recently discovered archive of early work, including some works that have never been seen before – will be unveiled to the public. Although Arbus had been taking pictures from the age of 18, she herself marked 1956 as the year she became a photographer, scrawling #1 on a roll of film that year. The photographs on view at the Met Breuer, shot on 35mm film, focus exclusively on her first seven years, also her most prolific time, from 1956 to 1962: a highly significant period in understanding Arbus’ pictures and aesthetic.

Ahead of the exhibition’s opening, we discussed work on display and Arbus’ impact and influence with Jeff Rosenheim, Curator in Charge of the Department of Photographs at Met Breuer, who has worked with her archive for many years.

On how this early work came to light…

“Arbus’ early pictures were seen in the day by folks, but after the 1972 exhibition, the first posthumous show, which happened a year after she died, they were not included in the publication, and it’s from the publication that most people know her work. So when there were small or even large shows, such as the Revelation Show (2003) those exhibitions did include pictures from 1956 to 1962, but they were not seen on their own. This exhibition was an opportunity to use the unparalleled resources of the Diane Arbus archive that we have at the MET, to look at those first seven years.”

On the role of her early work in her oeuvre as a whole…

“The difference between what happens in 1962 and what happens between 1962 and earlier is not so great in my opinion, but there is a contrast in format. In ‘62 she got a new camera, a Rolliflex which made a two and a quarter inch, square negative, and most of the work after that was made in that format, while most of the early work was made in 35mm, which is a rectangular format.

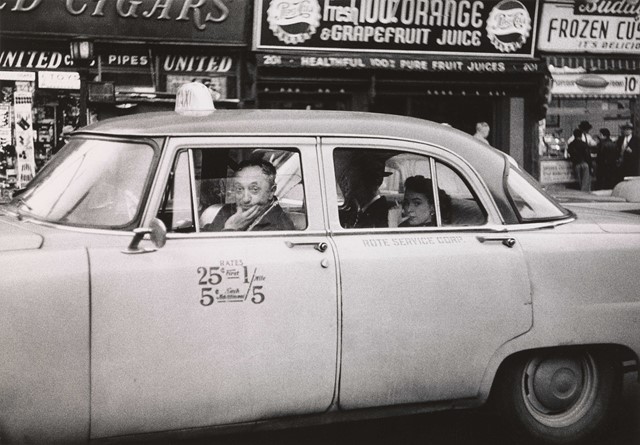

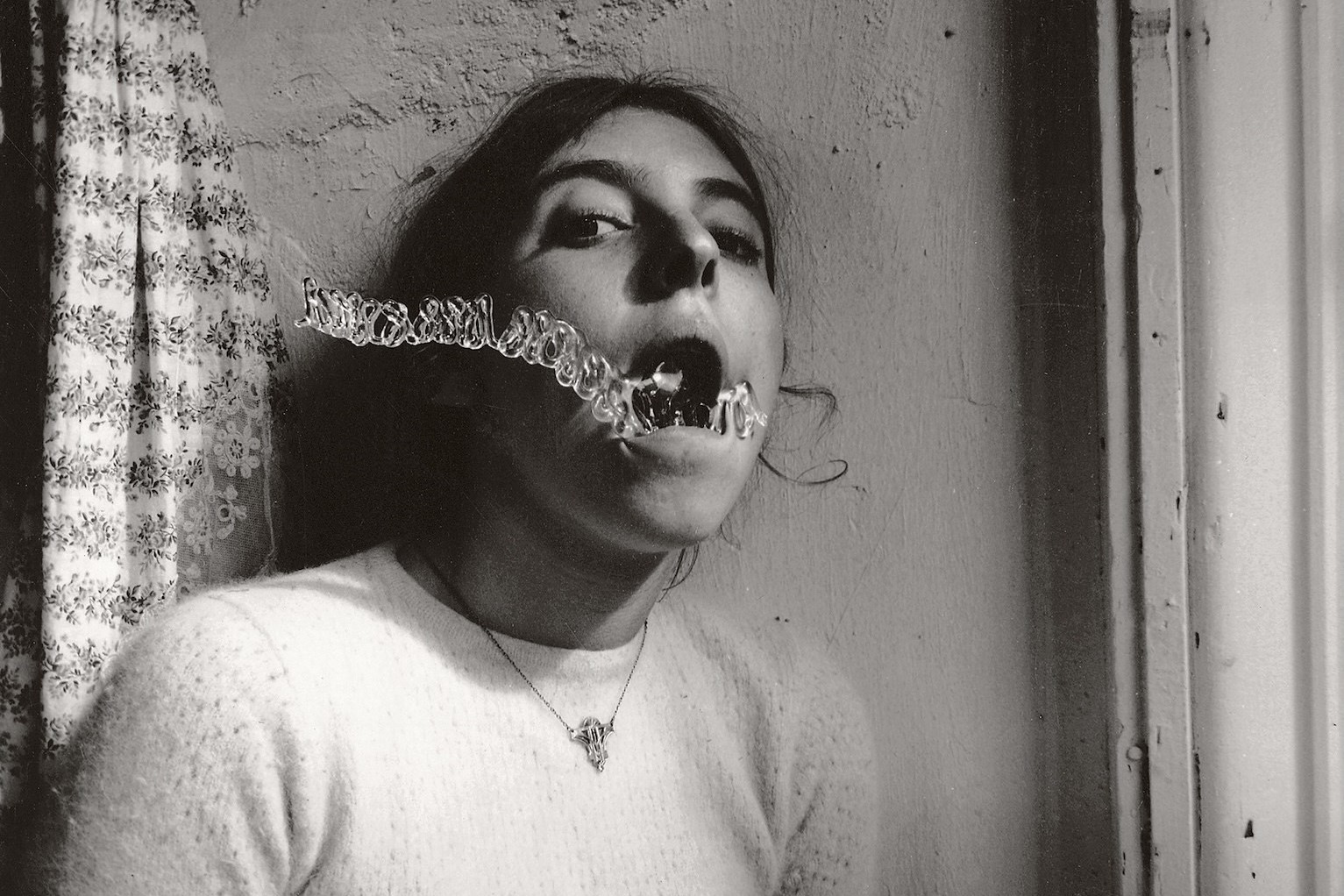

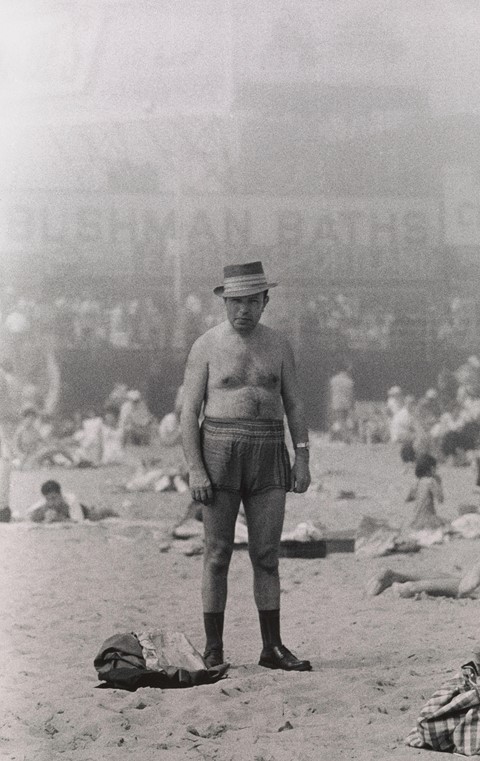

When we look at the pictures from 1956 to 1962, what we’re seeing is many of the same places, locales, and subject matter: everything from visitors and beach-goers at Coney Island, to film-goers in Times Square and pedestrians on 5th Avenue to female impersonators and people who performed, whether they were working in circuses or at the carnival, waxworks at Coney island or Times Square. The subject matter is a through line from beginning to end.

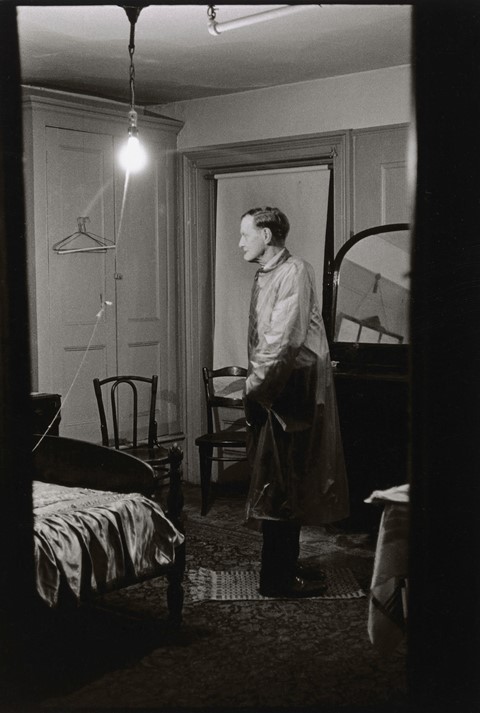

But there is one change, which is that she generally worked from outside to inside, and in the earlier work she is more often photographing individuals on the street and then making appointments to meet other people; then as we move forward in time, until 1962 to 1964 and then to the end, she is really working as often as possible with people she has arranged to meet, there are fewer chance occurrences in the work. That’s a small border of difference.”

On why her legacy lives on today…

“There’s an authenticity to Arbus’ pictures and her style – the straightforward, documentary style – but there’s also this very deep feeling that visitors to her shows have, a profound experience. When you see a Diane Arbus picture, in the flesh or even in reproduction, you’re seeing a distinctive expression, an artistic expression of uncommon truthfulness and veracity. They’re idiosyncratic, and that’s why her work is such a touchstone for so many young artists – they’re searching for their voice and they can see in Arbus that great voice.”

On the way she depicted her subjects...

“Every artist has to look at the world and try to understand it, and try to understand who they are. I would say that the exposure that you talk about, the revelation that you feel when you confront her pictures, is as much about who we are, as viewers, as who the subjects are as individuals.”

On Sontag’s ideas about who Sontag photographs for, and how her audience has changed…

“I never had the opportunity to discuss with Sontag her opinion about Arbus’ work. When we were doing the Revelation show I actually wrote to her to ask if she would join me on a panel to discuss Arbus’ pictures but it turned out to be a time when she was unwell, and then she died, and so I never had the chance to ask her those questions about how the times were different. I disagree with most of Sontag’s opinions about Arbus, and I would imagine she might have disagreed with her own assessment of it, if she were given the opportunity, but we’ll never know that. I would say that today her work is seen as one of the great bodies of work, one of the most authentic expressions of what the medium of photography can do.”

On the quintessential ‘components’ for an Arbus picture…

“Direct view of the subject. Intimacy. Generally an eye-to-eye relationship between the subject and artist, and therefore to the viewer as well. The feeling of a secret, or an expression of individuality, being shared between artist and her subject. Physically: an extraordinarily beautiful object. This exhibition may be the only one that has been done, certainly in my lifetime, that exclusively features works printed by the artist herself. Not posthumous prints, but works made by her in her darkroom, and they have a kind of virtuosity of expression that I find very telling.”

On his highlights from the exhibition...

“I’m particularly drawn to man in hat, trunks, socks and shoes, Coney Island, NYC (1960). I find that picture to be quite evocative of how she worked, seemingly able to separate the individual from society yet allowing you to know where she is, and how that individual was magically drawn to her as much as she was drawn to him.

I very much like Backwards Man in his Hotel Room, NYC (1961). He’s a performer, he’s a contortionist, and the way you enter the picture, you’re in his hotel room but you see the door frame, and you have this raw light hanging over the figure. You have to pay attention to see that he’s looking in one direction, and his feet are going in the other, and he’s in this sort of clear raincoat… All of the levels of description, the emotional description, the relationship of the figure to the ground, and the lighting, contributes to a very powerful picture.

I’m also very keen on some of the pictures of kids; there’s a picture a young boy at the curb turning back to look at the camera… but what you’re asking is where the viewer should be drawn to, what the keynote pictures are, and there are so many. There are also extensive photographs where there are no people in the pictures at all, and those images have equal potency and value. I’m as drawn to them as I am to any of the others.”

Diane Arbus: In the Beginning runs from July 12 until November 27, 2016 at the Met Breuer, New York.