Open up Andy Warhol’s medicine cabinet and you would have found Shelly Marks Potpourri, Xerac BP/10 “for treatment of Acne,” Exsel Selenium Sulfide Lotion “for scalp,” Interface Herbal Rub Scrub and Cetaphil Lotion Lipid-Free Skin Cleanser, among an assortment of other fragrances, potions and personal hygiene products designed to massage both a face and an ego. For someone who deified commerciality on his canvases, any one of these items could have been his next painting. But it was perhaps this medicine cabinet itself which was Andy Warhol’s last great work of art.

It hung in the bathroom off of Warhol’s bedroom on the second floor of his townhouse on East 66th Street in New York. Behind the many bottles was a mirror to increase the quota. Through the years, it has become something of enduring fascination, an artist lore. His former Interview employee and friend, Bob Colacello, scribbled down the cabinet’s contents on the back of some business cards when he visited the apartment, his first time, following Warhol’s death. Those products were “just the beginning of what Andy Warhol thought he needed to face the world,” Colacello wrote in the last sentence of the epilogue in his 1990 Warhol biography Holy Terror.

Poring over the curiosities of his medicine cabinet at his last ever residence was part of a ten-day job for photographer David Gamble. He was commissioned by Warhol’s business manager, Fred Hughes, to photograph the 8,000-square-foot home on East 66th where Warhol lived and hoarded from 1974 until his death in 1987. It was there he kept his 610 cardboard time capsules. All of his possessions were to be sold in a titanic Sotheby’s auction in 1988. The cabinet was also photographed. A work of art. Gamble’s photograph of Warhol’s private repository of products fetched $25,000 at auction. It now resides in the permanent collection of the Andy Warhol Museum. “What I’ve done is I’ve made people a voyeur,” Gamble explains of the cabinet’s undying intrigue over the phone. “Bathrooms are very private: that’s where you have your hair removal cream, your Vaseline, your Lip Smackers, your fashion tan, and any ailments or skin problems you have will all be revealed there. That’s probably why people love that medicine cabinet.”

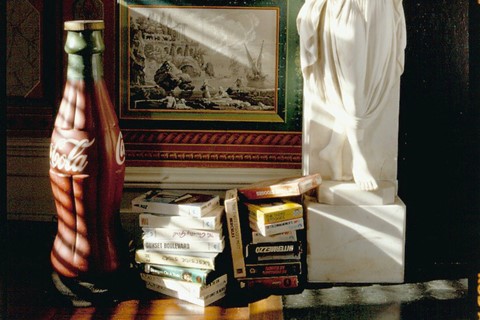

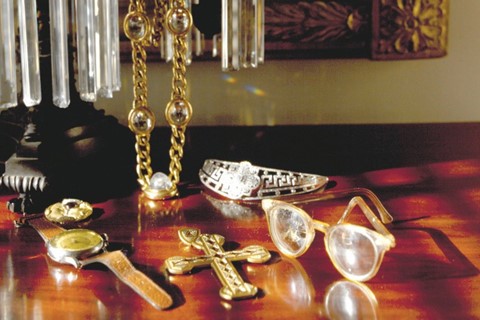

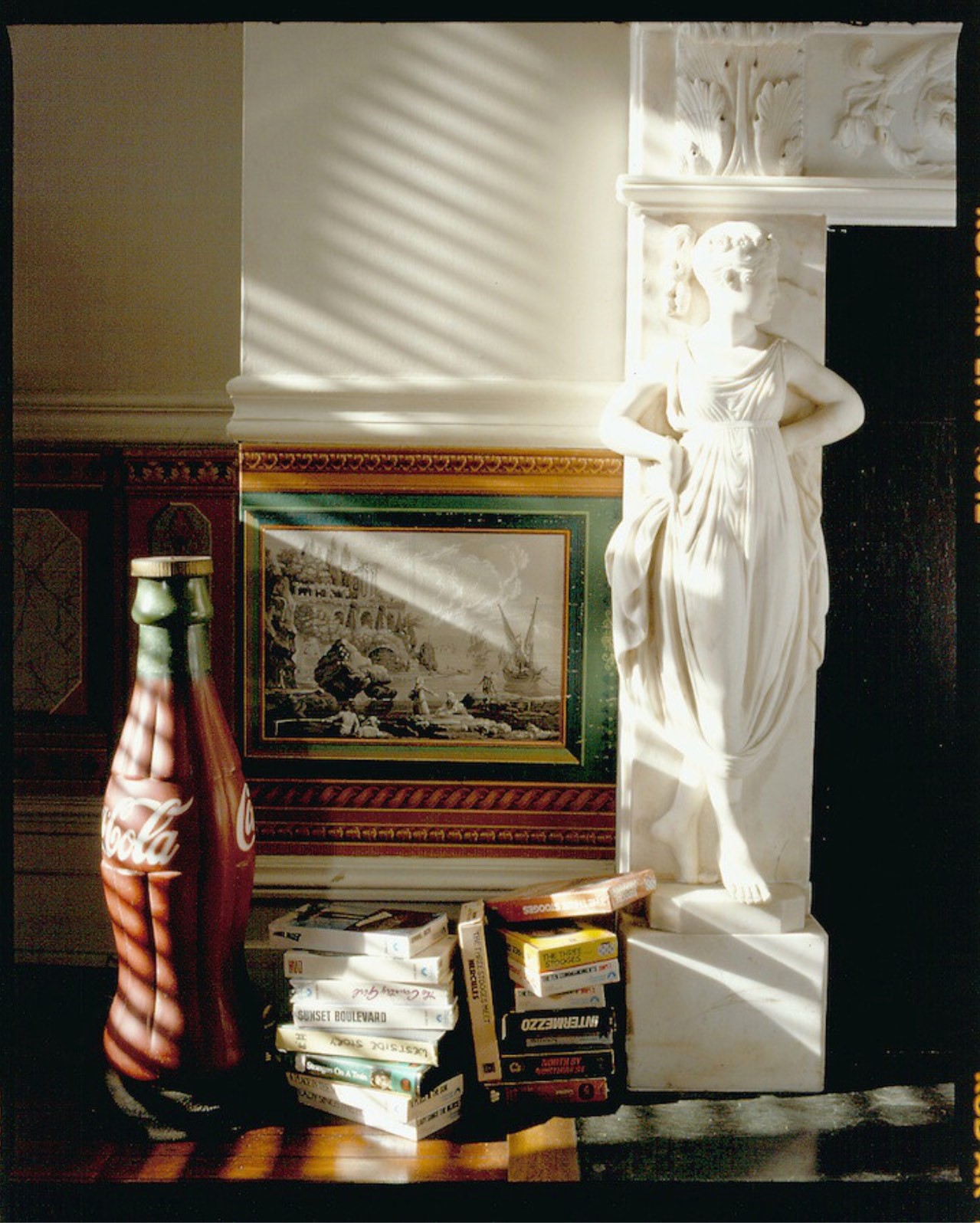

That may have been the most revealing artifact in a collector’s Shangri-La, chockablock with invaluable treasures. East 66th Street was described as “the richest street in the world” by Warhol in The Andy Warhol Diaries. Imelda Marcos, the former First Lady of the Philippines, was his neighbour. (Warhol used to mistakenly receive the Marcos’ electricity bills.) Former US president Ulysses S. Grant, too, lived and died on that street. Warhol’s sliver of a townhouse was purchased for $310,000 from one Mrs Bartow. His lover, Jed Johnson, ran an interior design business from one of the upstairs rooms, with Warhol’s support. He decorated the space with a mix of the pop artist’s tchotchkes. A Mexican crucifix; a Jersey Jim “Punch” figure; fine art, including Maxfield Parrish and Jasper Johns. Walking into the entrance hall revealed a winding staircase to the second floor, Gamble recalls. Upstairs was the street-facing living room, minimally decorated, Roy Lichtenstein’s Laughing Cat on the wall, and the parlour, a more puritanical affair with Victorian Egyptian busts and a chair with gilded feet. The former owner, Mrs Bartow, an entry in Warhol’s diaries reads, “asked when I was going to sandblast it and why was I never home because it always looked dark”.

Shuffling around 1950s-era cookie jars (78 of the 175 jars went for $250,000, a record for a lot of cookie jars sold at auction) and vibrant fiestaware, Gamble worked long hours to “find a portrait of Andy in the pictures that I was taking”. Often, he would stay until 10, 10:30 at night. “There were a couple people spooked being there late at night,” he remembers. “I enjoyed the strange atmosphere and heaviness about the place. They thought it could’ve been haunted by Andy,” Gamble says, adding with a laugh, “Why wouldn’t you want to be haunted by Andy?”

He had some secrets there, too, hidden away. Notable feature: Warhol’s master bedroom allegedly housed a secret trapdoor. Gamble tells me he never noticed it. “There was a maquette upstairs in the bathroom, a door handle,” he continues. “It was a piece of [Marcel] Duchamp’s that was molded around a woman’s part. A butt part. [laughs] I thought it was a door handle when I picked it up. It looked like a door handle…” He also had a gold brooch in his bedroom designed by Salvador Dalí.

Following Warhol’s death in 1987, the street number, 57, was snatched from the building’s facade. It was replaced by a plaque commemorating the Pope of Pop Art. In 2000, the Lenox Hill townhouse was purchased by Tom Freston, then chairman of MTV. A current estimate puts the townhouse at $19,964,999, or a lot less than the cost of one Andy Warhol painting. More photographs of Warhol’s sanctuary exist, Gamble avows, “but I ain’t gonna look for them. There’s something in life where it’s best to hold back at least one or two things just to surprise people later on.” His belongings have been scattered, redistributed to collectors, family members, vultures and some, possibly, to the dump. But that’s not likely, considering how fans continue to survey his bathroom products, examining bottles and flagons and tubes with the same awe as one of his screen-printed Campbell’s soup cans.

With thanks to David Gamble.