Before he made films, Michelangelo Antonioni wrote about them, and Vittorio Mussolini, son of Benito, was director of the first film magazines he worked at (and got fired from)

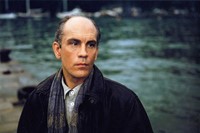

Michelangelo Antonioni began his career, like many other filmmakers, as a keen observer. Best known for his languid monochrome portraits of middle-class ennui, as epitomised in classics such as L’Avventura and La Notte, this February the award-winning Italian director is a subject of the BFI’s spring season. Antonioni is the director many love to hate; his long, lingering shots, coupled with a disregard for plot and pacing, created films that were considered difficult or hard to digest. Although other aspects of his life are well documented, such as his complicated relationship with his muse Monica Vitti, a crucial time remains relatively unexplored. As a young man, rather directly, fascism changed the course of Antonioni’s life.

In 1940, the young Antonioni upped sticks from his hometown of Ferrara with a portfolio of film reviews to his name, and headed south to Rome to seek his fortune. Trading in his writings for local paper Il Corriere Padano, after working as a secretary and bank teller, he finally managed to get a job writing and later editing for the newly founded magazine Cinema. With an international circulation and wealthy backers it was a definitive step-up for the young film enthusiast. The only problem? The magazine’s director was none other than Vittorio Mussolini, the second son of Benito, Italy’s fascist dictator.

Although in some regards Vittorio was clearly not his father’s son – he loved Hollywood, rejected his father’s racism, and embraced many left-wing and Jewish directors, writers, and film critics – he remained a loyal supporter of the fascist regime. After only a few months of work at the magazine, Antonioni was fired. While the details surrounding his dismissal are vague, it is clear that it came after strong political disagreements between the left-wing future film director and higher management. No notice was given, the decision was effective immediately. It was a formative experience for Antonioni, a period he recalled as full of trauma: “When they fired me I was penniless for days. I even stole a steak from a restaurant.”

Antonioni only survived the following months by selling off the precious tennis trophies that he’d won as a young boy to finance his stay in the eternal city. He had already enrolled at Rome’s Experimental School for Cinematography, and now began collaborating with other up-and-coming talents such as Roberto Rossellini, writing screenplays and assisting established directors. In short, his dismissal forced him to confront his desires and push him into the practical world of film making over film watching and reviewing.

In 1942, he travelled to France to work with Marcel Carné, and would have stayed on to work with Cocteau but fate had other plans. Antonioni found himself back in his hometown when he was called back to Italy for military service. Here he set about raising funds to produce his first film. The project was based on an article he had written for Cinema in 1939 about the life and work of fishermen living alongside Italy’s longest river, the Po. Started in 1943, filming was disrupted by the war, during which time Antonioni refused to aid film work for Mussolini’s ‘Republic of Salò’ under the Nazis, choosing instead to join the underground network of the anti-fascist Action Party.

German forces destroyed much of his film footage but what remained was edited to produce a short documentary, Gente del Po (People of the Po Valley), which finally made its debut as a curtain-raiser for Alfred Hitchcock’s Spellbound at the 1947 Venice Film Festival. Skip ahead to 1964, and it is Antonioni’s film Il Deserto Rosso (Red Desert) which is being screened for audiences at the festival and wins the famous Golden Lion. “I have never thought of labelling what for me was always considered a necessity, i.e., to observe,” he noted in an essay for Film Culture two years previously. “I detest films that have a ‘message’. I simply try to tell, or, more precisely, show, certain vicissitudes that take place, then hope they will hold the viewer’s interest no matter how much bitterness they may reveal.”

For a man who lived, and for a time worked closely, under the fascist regime his words have weight: “Life is not always happy... one must have the courage to look at it from all sides.”

Michelangelo Antonioni at the BFI Southbank runs until February 28, 2019.