This article is published as part of our #CultureIsNotCancelled campaign:

Matt Wolf’s documentary Spaceship Earth, which premiered at this year’s Sundance Film Festival – and released digitally worldwide last Friday – charts the determination of a group of countercultural visionaries who used art and community to foster a connection with nature. Named Theatre of All Possibilities, the artistic-practice network built a junk rig ship that has sailed for the past 40 years, from which researchers have studied whales, coral reefs and disappearing tropical cultures. In the 1980s they designed airtight geodesic structures for the study of complex, evolving life systems, making unprecedented waves in the sphere of ecological study. As we reach the tipping point of a worldwide climate crisis, one of the collective’s founding members, Kathelin Gray, paints an inspiring tribute to its remarkable achievements.

Once upon a time at a bus stop in San Francisco’s North Beach, May 1967, on my way to a dance rehearsal, I encountered a raw-boned man named John Dolphin Allen. I had been raised among geologists and recognised the fire in his eyes as that of a fellow explorer: a treasure hunter like Walter Huston’s character in The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. A bibliomaniac and polymath, John spied the book I carried – René Daumal’s mid-20th century novella, Mount Analogue: A Novel of Symbolically Authentic Non-Euclidean Adventures in Mountain Climbing (see notes: 1), about a motley group of artists, scientists, philosophers and adventurers who form an expedition to an undocumented island in the South Pacific. I wanted to launch an expedition into history, like the book. So did John. He was planning to pass through San Francisco, but decided to stay on – a student of history, he had realised there was a rare opportunity in that moment of us meeting. We began a lifelong friendship and collaboration, and that night, we called friends to join us. The aim was simple: to make a difference.

A spirit of social experimentation, vigour and optimism filled the streets that summer in San Francisco. With the freedom of having nothing to lose came political demonstrations, concerts and large cultural manifestations that called for new values and identities. Most people knew then that there would be a backlash, but many lived in hope that social and economic justice could be achieved in our lifetimes. It was obvious that a radical re-evaluation of human society was essential to avoid planetary ecological catastrophe.

In August 1967, John, Marie Harding and I (2), together with five other friends, moved into a Victorian house on Sutter Street, near the Pine Street Commune and the Avalon Ballroom. We opened a cafe to support ourselves, while theatre offered the protected inner space we needed to investigate these goals. We created Theatre of All Possibilities (TAP) to investigate history through the lens of drama. We asked how to integrate the artists’ conscience into a new societal form, inspired by developments in science and technology as well as a deep connection to the natural world. We sought a world in which an artist could live free from poverty and alienation, where an artist’s life is her most important work. We studied the history of revolutions and of group-living experiments.

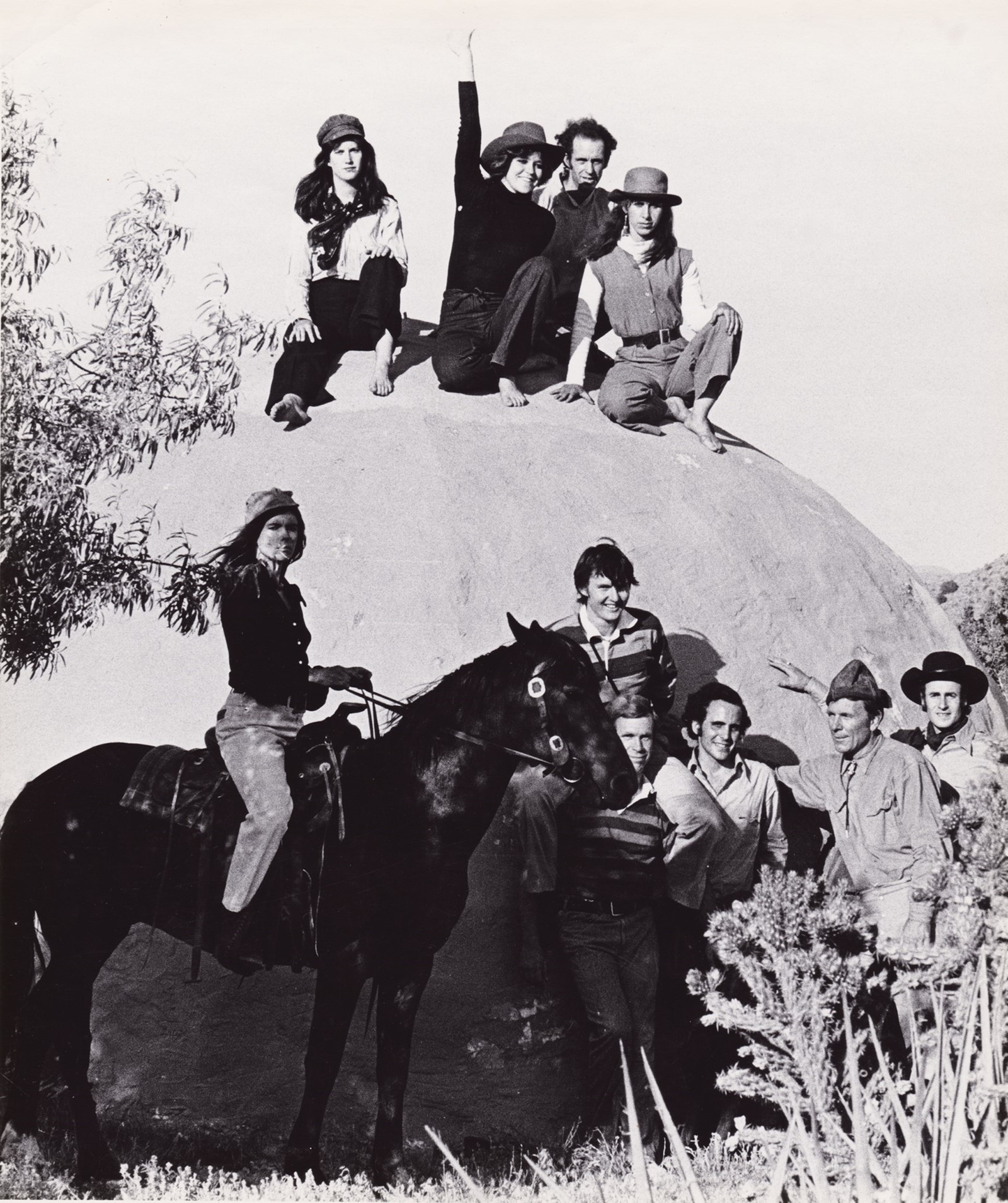

Defining a history can be like unravelling a complex textile, where one is left holding a bunch of coloured threads but the design has disappeared. An artist by nature, I view TAP’s history as a longform performance piece. Over the next 50 years, legions of dramatis personae would join us in an impossibly complex and dense plot. We formed the TAP ensemble, and the Enterprise for Developing Possibilities for project development. In 1969, we bought a ranch outside Santa Fe, New Mexico, which became a mother ship for other projects. The 1970s overflowed with seekers of a new way of life. Many navigated sputtering vehicles up the dirt road to our ranch, then plunged gamely into work and rehearsals. The eroded land had been overgrazed, and we took up the challenge to regenerate it and study ecology, and in the early 1970s, we formed Institute of Ecotechnics as a think tank for project implementation. Synergy, where the whole is greater than the sum of its parts, was and is our strategy.

30 people built a geodesic dome (3) for summer performance seasons. We opened small businesses that sold ceramics, leatherwork, clothes, woodwork and ironwork, as well as a printing press. We did acting exercises while planting gardens, voice work while making adobe bricks, ran lines while clearing badly eroded pastures of locoweed, and performed nightly improv sketches before dessert. One evening we held a War Against the Machine party, where everyone could act out road rage, smashing and burning an old automobile to smithereens.

We wanted to make contributions to ecology and to history. In the 1970s, many groups formed in Europe and the Americas, moving onto the land and into abandoned city buildings. We wanted to accomplish one daunting task that would distinguish us from the other groups; we could build a ship and sail the seven seas, we could do anything, was the idea. John had seen the picturesque traditional boats in Hong Kong’s harbour and inspired the rest of us to build a Chinese ocean-going junk rig sailing vessel, and create a contemporary version of the age-old sea culture, with a commitment to ocean ecology. Under a kerosene lamp in an unheated studio, engineering calculations and plans were drawn up.

In the summer of 1974 we drove the tour bus to Oakland, California. In eight months, 20 of us built our ship on a marina that was deserted but for an array of sculptors, hippies and wannabe boatbuilders. Others back in New Mexico ran the ranch and a construction and architecture enterprise building adobe condominiums. It’s hard to imagine now, but there was no internet or social media, there were no mobile phones. Meatspace was life. We drove our bus along Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley, inviting street people to get in on our self-administered course, Shipbuilding 101. “Would you like to help us build a ship today? We serve macaroni salad for lunch!”

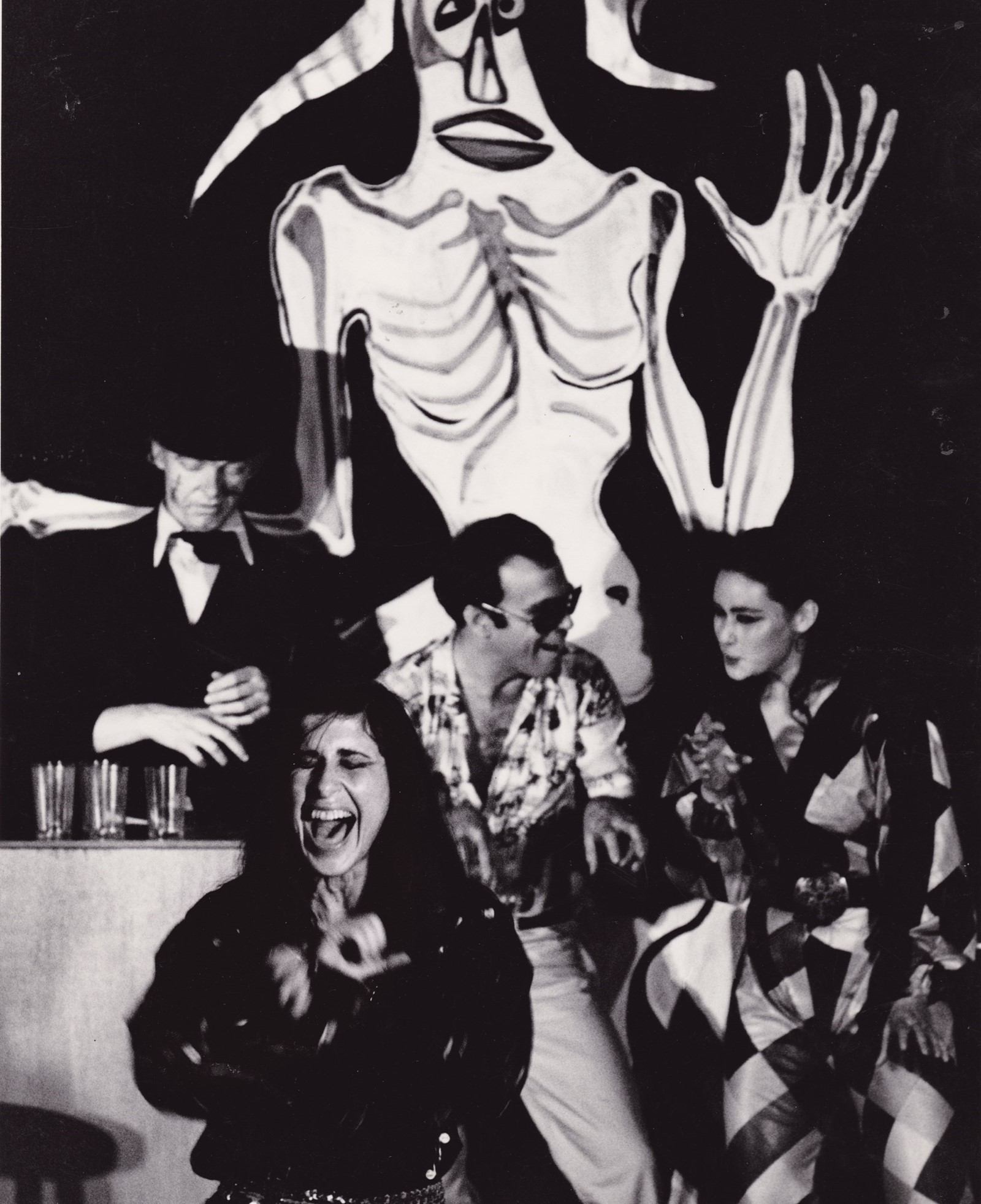

Simultaneously, I organised performances of Metamorphics in Theatre: Brecht and Artaud, about an imaginary meeting of the two influential 20th-century theatre practitioners. We toured LA with Carneval of the Seven Sins, a black comedy we had developed through improvisation about modern existence. Old salts inhabiting the docks bet that we’d never launch the ship, and that its skeleton would join the other abandoned half-built hulks littering the marina. We made many a Sunday toast to the spirit of the ship, which, like a benevolent alien goddess, seemed to be building herself despite all odds.

Typically working 18-hour days, in eight short months we constructed the 25-metre ferrocement sailing vessel. Our target was to take advantage of a very high early spring tide. And so, just after sunrise on 22 March 1975, a tugboat pulled our new ship, christened Research Vessel Heraclitus, into the San Francisco Bay. It was a mystical experience on deck to ride her momentum into the bay, like moving through the birth canal. We unfurled a Panamanian flag. According to maritime law, we were legally in Panama, even though we were floating off the coast of California. Over the past 40 years, the ship has sailed more than 270,000 miles in 12 expeditions – the Magic Black Ship, as people all over the world have called it.

The crew has now circumnavigated the globe, studied whales in the Antarctic, mapped coral reefs in South East Asia and the Red Sea, filmed disappearing tropical cultures in the South Pacific, helped release captive dolphins into the wild, documented legacy coastal cultures in the Mediterranean. The current captain and expedition chief have lived on board for more than 25 years, and are rebuilding the vessel for the next generation of sea people to steward the health of the ocean and support disappearing and new cultures that protect local ecologies.

We acquainted ourselves with terms such as biosphere, biome, epoch (as in geologic epoch), rejecting identification with national boundaries or arbitrary divisions of time and space. The word ‘environment’ assumes an artificial barrier between humanity and the rest of nature. In the 1980s, ‘biosphere’ was not in common usage, even ‘ecology’ was rarely uttered. We devoted the late 1970s and 1980s to creating demonstration projects in the Earth’s other major biomes – desert, forest, savannah, and more. No dogma. No belief system, but individual quests, the arts, group projects and individual enterprises. Our collaborations expanded to include a touring ensemble, the research institute, the October Gallery in London, a sustainable forestry project in Puerto Rico, a hotel in Kathmandu, a savannah-restoration project in Australia, a conference centre and organic farm in Provence, and a network of friends spanning the globe.

Institute of Ecotechnics held annual conferences with scientists, adventurers and artists including Buckminster Fuller, Richard Dawkins, Thor Heyerdahl, Lynn Margulis, Sir Ghillean Prance, Antony Gormley and many others. Preventing the impending climate crises was always on our mind, and we hurried to establish our demonstration projects so they would be in place before full-blown, irreversible disaster was reached. In 1980, we held a conference on the state of the planet with speakers including climatecrisis specialist James D Hays, William S Burroughs on the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, and Alexander King, co-founder of the Club of Rome, which in 1972 published a landmark report warning of upcoming planetary crisis.

Biosphere 1 (B1) is life on Planet Earth. Biosphere 2 (B2) began with a dream. John’s napkin scribbles dating back to 1968 trace the designs of a small project, a futuristic ecological community. We had years of discussions among ourselves, and with scientists of all kinds, including space scientists. In one iteration, John dubbed this future project Spaceship Earth City, after Buckminster Fuller’s term for our blue home that hurtles through space, Spaceship Earth.

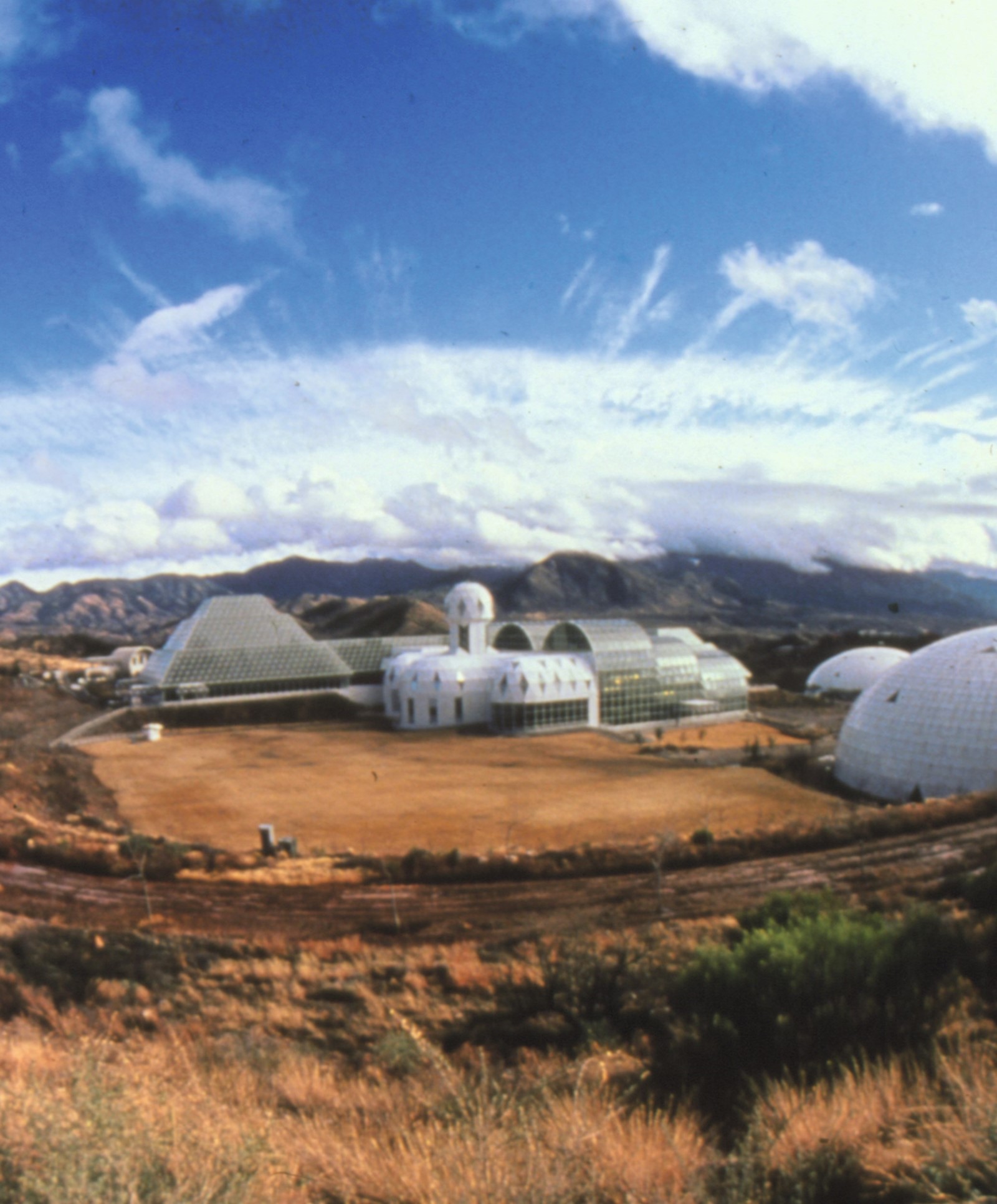

In 1985, we purchased land outside Tucson, Arizona, to build B2, an airtight terrarium designed to house 100 years of experiments investigating complex life systems for space colonisation and evolution. In 1989, a 1,500-square-foot module was built to test structural elements for short-term viability of a closed system – a sealed, isolated environment – consisting of just plants and one human. We would find that, within a closed system, metabolic cycles accelerate, creating an ecological cyclotron (a particle accelerator) that facilitates observations of small-scale interactions.

In six short years, the team designed, engineered and constructed the ambitious B2, more than three acres in size. Ecotechnics, as scientific coordinator, collaborated with many institutions; this groundbreaking project engaged 200 scientists and engineers, and hundreds of others. Field teams collected flora and fauna from North and Central America, the Caribbean and Africa, which were then planted in a facility and lab on-site in preparation for life inside B2. Our primary scientific strategy was akin to a naturalist tracking an ecosystem, like Darwin’s Voyage of the Beagle, where observations yield crucial new knowledge about how life systems interact.

In September 1991, four men and four women entered B2 for two years. This first crew raised 85 per cent of their food, and everything inside, including air and water, was recycled. Their office was paperless, and they had telephone and electronic communications with the outside world (4). The world’s press compared it to a moon landing. It was a major media event, and the inevitable controversies arose. When the crew exited after two successful years, nearly 1 billion people around the globe viewed their ‘re-entry’ to the outside world via satellite uplink. Classrooms throughout the US had adjusted their curriculums to parallel the time spent inside. In 1993, a second crew of seven entered, raising 100 per cent of their food.

Now a facility of the University of Arizona, which runs individual research projects and a booming visitors’ centre, it is one of the top ten tourist attractions in the state of Arizona. There’s a parallel between the late 1960s and 2020. Continuous war and assaults on ecologies and legacy cultures are at the forefront of people’s minds. Global cultural values and relationships with the natural world urgently need to be re-examined at the root. Mass extinction was well underway then, and a worldwide movement would have made a difference. Now we are reaching a tipping point, and there are new challenges, but a great many new opportunities to embrace if we choose life over extinction.

Notes

1) The first edition of Daumal’s unfinished allegorical novel was illustrated by the Spanish-Mexican painter Remedios Varo and inspired Alejandro Jodorowsky’s 1973 film The Holy Mountain.

2) John Dolphin Allen came from an Oklahoma ranching family, and was a writer/ metallurgical engineer trained at Colorado School of Mines and Harvard. Marie Harding was a painter who abandoned the life of New York’s social register. In Manhattan, they had frequented Max’s Kansas City, a gathering place for artists and power brokers, while Gray was a teenager, raised in a milieu of the City Lights literary scene, geologists and radical performance.

3) Geodesic structural design allows the creation of large spaces without supporting pillars, and the space-tomaterials ratio embodies engineer and futurist R Buckminster Fuller’s principle of “doing more with less”.

4) The oxygen declined over many months, which was mysterious at first, but because the system was tightly sealed, the missing oxygen could be traced using isotope analysis. It was found to have been captured in concrete, a major published research achievement of Biosphere 2.

Spaceship Earth was released on May 8, and is available on streaming platforms. To find out more, visit the documentary’s website here.

This story originally featured in AnOther Magazine Spring/Summer 2020, which is on sale internationally now.