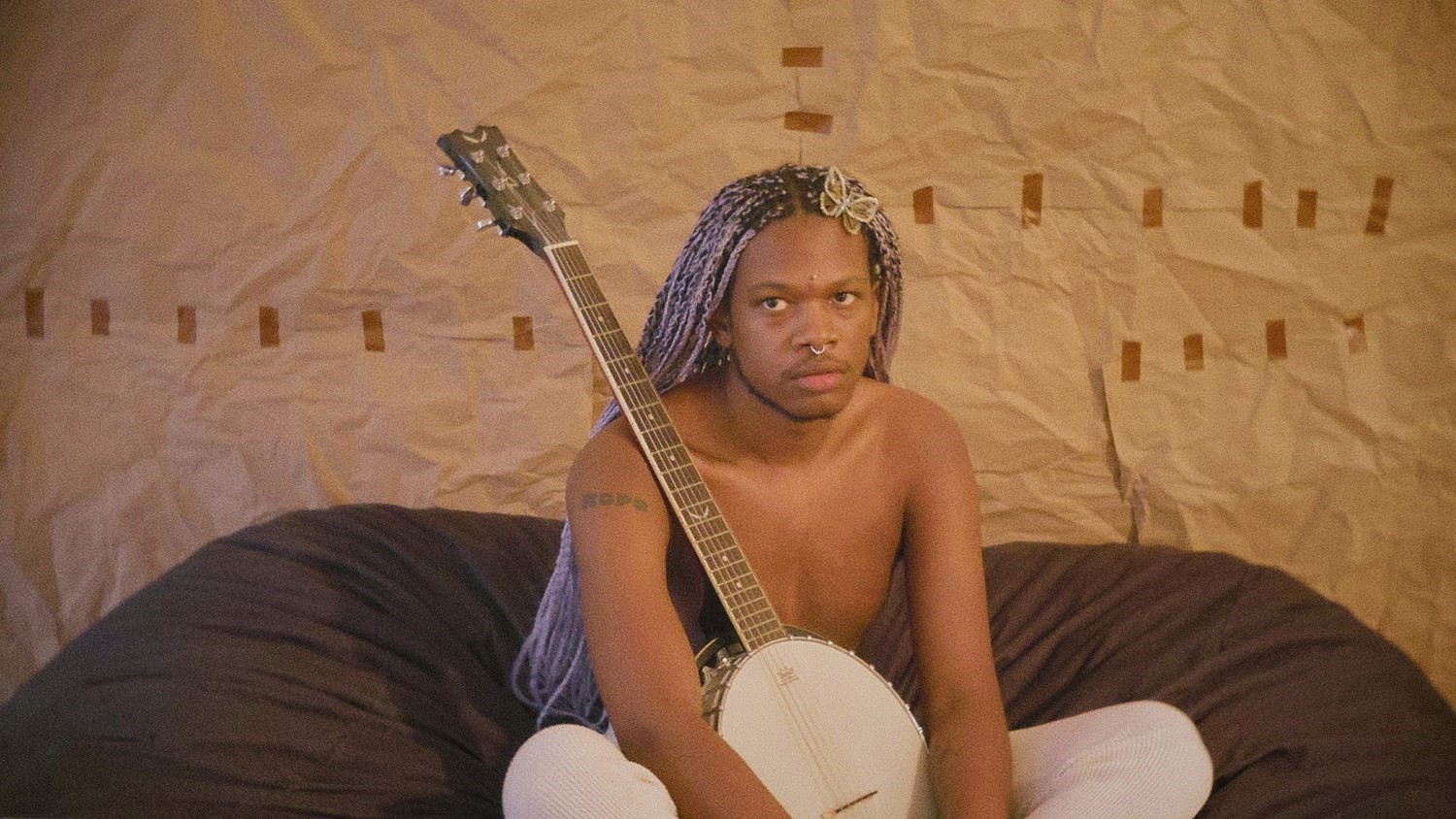

Five years after he released his debut album, Shamir is finally ready to make pop music again. The 25-year-old Las Vegas-born musician was one of the music industry’s buzziest new acts when he signed to British indie label XL aged 19, and with them he released Ratchet, a forward-thinking dance pop record whose influence can still be felt today. The subsequent half-decade, though, saw Shamir head in a different direction. Splitting from XL following creative differences, he recorded and mastered his follow-up, Hope, over one weekend in his bedroom, before sharing the album on Soundcloud for free. Soon after, he experienced a psychotic episode and was hospitalised; he was diagnosed with bi-polar. The subsequent years have seen Shamir, now living in Philadelphia, self-release a slew of DIY, lo-fi and experimental records.

Now, however, he’s ready to make himself accessible again; despite having already released a record earlier this year, Cataclysm, Shamir is readying his seventh, self-titled album. The album is a concise distillation of Shamir’s grungy sonic palette melded with irresistible melodies and slick production. Ahead of the record’s release, AnOther caught up with the singer over video chat.

Alim Kheraj: Hi Shamir! How has quarantine been for you?

Shamir Bailey: It’s been fine. I live alone, but I’m also very much [an] introvert, so I’m really fine on that front. I think if anything, I’m worried that I’m not going to know how to interact with the rest of civilisation once this is over.

AK: Once you release Shamir, you’ll have put out seven records in five years. That’s quite a lot.

SB: Is it? [Laughs]

AK: By today’s standards it is! How do you differentiate between each project when you’re working so quickly?

SB: I think that’s how I’m able to keep them different. Each project is just a snapshot of where you are at that point in your life. Because of that each record is different and sounds different; they have a life of their own. They are of that moment and so you’re not worried about consistency or continuity. You’re not even worried about who you are as an artist. I don’t approach every record making each one as if it’s my last, which a lot of people do. I’m trying to make a whole body of work. I feel like when I’m done with music, you’ll be able to start with Ratchet and work your way up and, essentially, piece my life together, which is what I’ve always wanted.

AK: Would you say that the experimental records sandwiched between Ratchet and Shamir helped you approach conventional songwriting in a different way?

SB: Yes, exactly. Essentially this record is the pop record that I always imagined for myself because it doesn’t compromise who I am as an artist in pop music. I think people look at what is popular right now in music and bring that into their sound. But I think with this record, and why I needed to do all those records leading up to this album, is I needed to find a way to bring current pop into my world. That’s how I feel. Look at On My Own, which I think encapsulates the precipice of all of it to me: it’s simple, lo-fi, it’s still drum, guitar, bass and not much else layered on to it, but still feels modern and fresh and nostalgic.

“Early on in my career, before I started diving into punk and grungier sounds, I wanted to be a country singer. I wanted to be Taylor Swift” – Shamir

AK: There’s a song on the album called Other Side that has this Americana vibe. What was it about playing with that genre that you wanted to explore?

SB: Early on in my career, before I started diving into punk and grungier sounds, I wanted to be a country singer. I wanted to be Taylor Swift. Country is special to me in a way that I don’t think any genre of music is. It speaks to a past life of mine. So, I went to Honky Tonks and did the whole thing. They were like, “He can sing, but he looks ... What is going on here? Can you at least try and put on a cowboy hat?” No! Even then I was so disconnected from how much aesthetics mattered. I liked country music and I wanted to do country music. I had my long dreads at the time, wore flashy colours. I was a weird hipster Black kid with his guitar singing Brad Paisley. People were like, “What the fuck is going on?” That made me very angsty, and that’s how I started getting into grunge. Essentially, that is more fulfilling for me musically; I have a lot of rage because of how the world treats me.

AK: I saw a tweet recently that asked the question about what your career would be like if you looked like Troye Sivan. You said that people weren’t ready for that conversation. That was weeks ago and a lot has happened since then. Do you think that things have changed since then that people might be willing to have that conversation?

SB: I was like, maybe I spoke too soon? [Laughs]. The world on the whole is ready to have a lot of conversations. But even then, on the grand scheme of things that seems relatively petty. Look, I toured with Troye. He’s one of my friends. The last thing I want to do is make it look like I’m pitting myself against him. But the fact stands that I do think I’m as talented as Troye. There are parts of my career where I’ve denounced pop, but part of me thinks how much more revered Troye would be if he had gone off to make weird indie-rock records that he played everything on and produced himself and released every year. I can imagine that being received better than it was received for me.

AK: Do you think you’ve become more assertive when it comes to your career in terms of the differences between artists and what you feel you’re entitled to?

SB: I can’t do that. I feel like if I do that it’ll be enough to make me go mad. I do everything just for the sake of art because that’s all I can do. I know that what I put out is always going to be undervalued. It always has been. Even when people look at Ratchet. Ratchet was a success and everything, but look at how much people have taken from that album and are still taking five years later. I made it with pennies! My whole career has been undervalued. That’s something that I’ve had to live with and [now] I put all my energy and focus into making the best possible art that I can.

AK: When Ratchet came out you said you wanted to lead the way for a slew of non-binary Black pop stars. That didn’t happen. What’s it like to still be leading the way in that respect?

SB: It’s deeply frustrating. I thought that releasing Ratchet and leaving would be enough. I really did. And the fact is, I didn’t see enough artists like me being given the platform that I had or higher. But it just didn’t happen and that frustrated me.

Realistically I wanted to be the weirdo indie rockstar making weirdo records for the rest of my life. That is me and that is still apparent in this new record, but I wanted to do whatever I wanted to do and be selfish in a way that my specifically white, specifically male and specifically straight contemporaries get to be. However, when you’re a part of not only one marginalised group but multiple marginalised groups, that weight does fall on you. It’s not fair, but it does. I think had to work through that. It’s not fair and I know it’s not fair. But I have to do this to be the change that I want to see in the world. If anything, me returning to pop and making myself accessible again isn’t for me. It’s for everyone like me.

“As much as I want to be my own person, I think it’s incredibly reckless when people who are in the margins get a platform and don’t use it to lift up other people like themselves. So I take one for the team” – Shamir

AK: When your identity is politicised without you even being born, it has such an impact that people don’t even understand. You can’t move without your life being a statement. You’re an activist because you exist.

SB: It’s not even that. I think that’s how I did feel. I felt like I was cosplaying activism, even though I never viewed myself as one. I was frustrated by that. But like so many things, it’s just another thing to bear: being Black, being queer, being all of these things. But being labelled an activist is put on you because you’re a public person. I have this problem because I have this platform. That is fairly easier than racism, which I’m not sure is every going to go away. As much as I want to be my own person, I think it’s incredibly reckless when people who are in the margins get a platform and don’t use it to lift up other people like themselves. So I take one for the team.

AK: If you can, how would you describe 2020’s energy?

SB: Transformative. It sucks, but transformation is hard. It’s not easy. But things have to die in order for things to be born. When people say abolish the police, we mean that. It’s not reform. You have to get rid of the old to get something new. You can’t keep trying to gloss over the old when it’s literally decaying. Everything has an expiration date. Trying to hold on to things that are past their expiration date prevents the new from coming in. These things are going to continue to happen around the world, but specifically in America. They are going to keep happening until we throw out the old, start over and allow space for the new.

Shamir is out October 2, 2020.