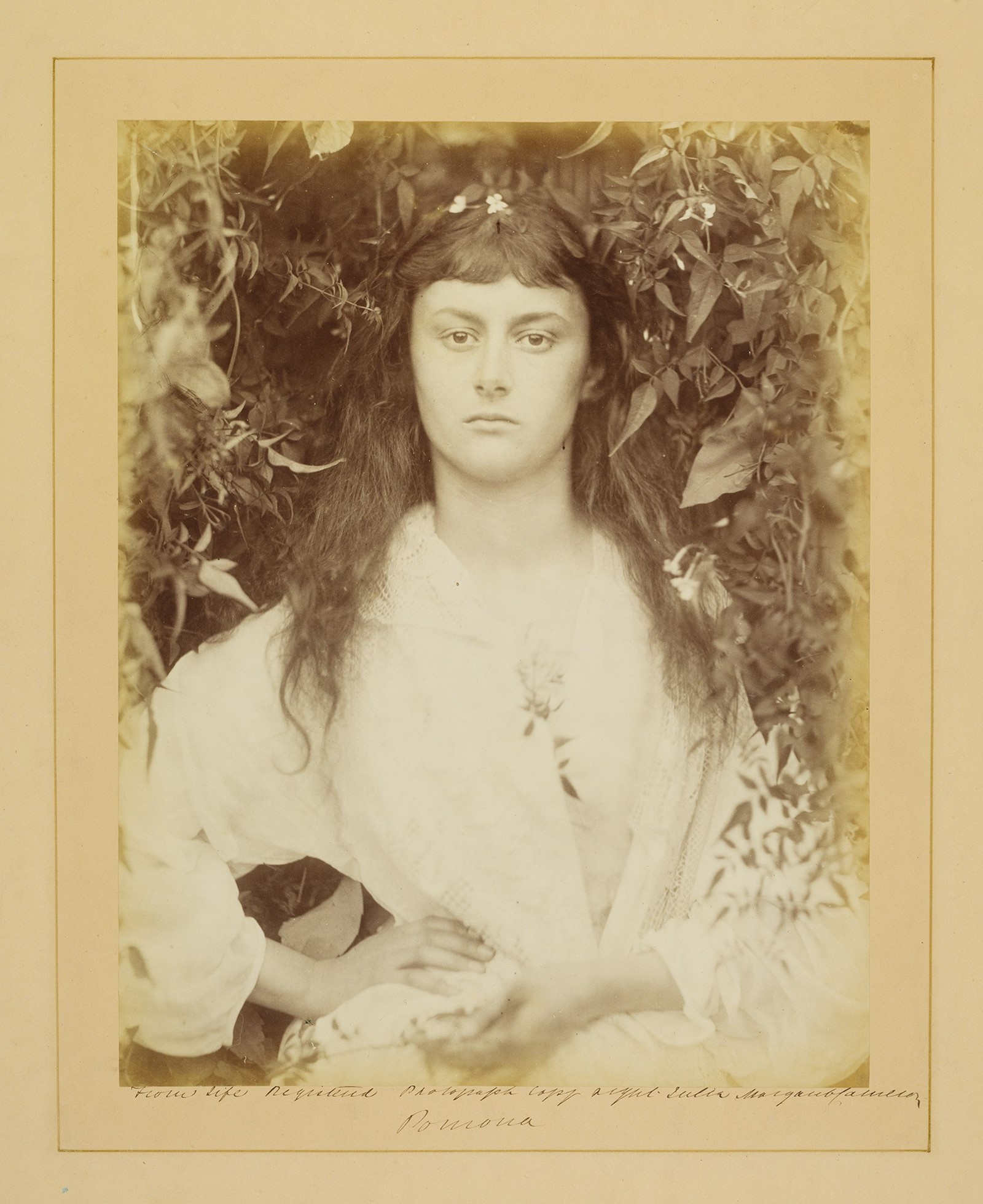

When it comes to visualising Alice in Wonderland, the classic blue dress, white pinafore and long blonde hair immediately come to mind. But there’s also that somewhat angry face, twisted in frustration. That comes across in the original published version of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, in 1866, for which illustrator and engraver John Tenniel set down an aesthetic blueprint for future depictions, but also lent the protagonist an older, knowing face that is almost permanently frowning. In Tim Burton’s live-action films for Disney, Alice in Wonderland and Alice Through the Looking Glass (2010 and 2016 respectively), Mia Wasikowska’s pale, solemn face and level stare centres the CGI chaos of the director’s imagination. But nothing could be more pensive than the last photograph Carroll took of the girl the book was originally written for, Alice Liddell, when she was 18. Taken around the time his sequel title Through the Looking Glass was going to press, and ostensibly in order to announce Liddell’s eligibility for marriage, the portrait sees her appear like so many teenage girls who come to later resent their documentation by adults – her stare, though direct, seems to look through you to somewhere beyond, where she would rather be.

Like many relationships of fascination between male artists and extremely young female subjects through time, the nature of the relationship between Lewis Carroll and the children he enjoyed spending time with remains both an unsolvable mystery derived from a particular historical context and a subject of uneasy, continued speculation. Carroll, an academic, was a family friend of the Liddells, whose patriarch was the dean of his Oxford college Christ Church; he told the first version of his story to Alice and her sisters after a boat trip he took with the girls. But though a new exhibition at the V&A, Alice: Curiouser and Curiouser, explores the context in which the books were first written by Carroll, the curators’ real calling is to trace the thread of Alice as a cultural symbol in art, advertising, film and fashion. Developing through stage and screen, Alice becomes a vehicle for a different and more radical kind of storytelling about girlhood in the 20th century, a trait which continues to accelerate into the now. And although adolescence wasn’t yet a voiced concept in Victorian times, Alice is a kind of ur-example of the kinds of subjects this column examines – a blueprint for how we understand coming-of-age, containing ideas that have continued to stick.

This is all despite being a story about, as well as written for, a seven-year-old girl. But the story of Alice is also a chronicle of a changing, unpredictable body – something unavoidably tied up with going through adolescence. The earliest theories of adolescence were grounded in the physical sensations of an awkward, changing body; G Stanley Hall’s 1904 study, which is widely viewed as the beginning of a scholarly field of adolescence, observes the rates at which different parts of the adolescent body grow at different times. But Alice, whose time in Wonderland is defined by consuming items that cause her to become too little or large for her situation – at one point her neck grows to a giraffe-like length, so that “her shoulders were nowhere to be found” when she looks down – actually predates such studies by nearly half a century. And apart from Alice’s acute awareness of these literal bodily changes, there’s a kind of adolescent self-consciousness that also weaves its way throughout the books, with encounters with different characters always leading to muddled interpretations in which the heroine tries – and fails – to make herself understood.

But Alice’s attachment to ideas of adolescence has established itself way beyond Carroll’s text, or its printed illustrations. Through film, theatre and fashion, the character’s image breaks away from the Victorian context to experience a kind of 20th-century coming-of-age explicitly through the visual. As the notes for Curiouser & Curiouser state, there have been hundreds, if not thousands, of theatrical productions of Alice over the centuries, and what feels like nearly as many film adaptations. These include literal adaptations, like a live-action Pre-Code Paramount Pictures production with a young Cary Grant, weirdly, as the Mock Turtle (1933); Disney’s psychedelic Alice in Wonderland animation, who we can probably blame for the extremely blue-eyed blondie that forever stays in our mind’s eye (1951); or the darkly fantastical Alice by Czech director Jan Švankmajer. In the latter film, the provocative director crafts a Joseph Cornell-like series of boxes through which Alice has to squeeze herself through – a world of broken-looking stop-motion creatures, made of real materials you might find in the house, that makes for at-times frightening viewing (the voiceover preamble appropriately states it as a film “made for children – perhaps”).

While the worst performed versions of Alice are those that move away from her own perspective to focus on the other fantastical creatures, others have dug down into the core story of, simply, a girl trying to find her identity. In the Damon Albarn-soundtracked musical wonder.land that played at the National Theatre in 2015, the rabbit hole became the internet, and Alice became a mixed-race teenage girl who is struggling with a difficult home and school life. Her virtual avatar in the wonder.land game that she immerses herself in is the classic, blue-eyed, blonde-haired Alice – a detail which thuddingly confuses “finding yourself” with fitting into white, mainstream environments. Still, the idea of a pre-algorithmic internet feeling like Wonderland – all unexpected encounters and new identities to try out – speaks to the character’s continued relevance. When Legacy Russell champions the idea of the glitch in Glitch Feminism, she could be talking about diving down a rabbit hole. “Through the digital, we make new worlds and dare to modify our own. Through the digital, the body “in glitch” finds its genesis. Embracing the glitch … creates a homeland for those traversing the complex channels of gender’s diaspora.”

Ultimately, as fantastical as the homeland Alice finds herself in is, her preoccupations are often wedded to how moving through the world as a girl really feels. In a scene in Looking Glass where Alice takes a train without a ticket, the guard peers at her through a telescope, a microscope and an opera glass (Tenniel depicts Alice head-down, trying to avoid his gaze). Who hasn’t felt acutely observed as a teenager on public transport? It brings to mind the scene of Chihiro boarding the one-way train across the ocean in Spirited Away, not only because of the strange creatures who also join her in the carriage, but also because of the particular way Chihiro sits and looks out of the window, solemnly perched on the edge of her seat, and peers at the shadowy commuters who seem to lead completely separate lives. And as extreme as Alice’s changes in bodily scale are, preoccupations with how clothes fit are an adolescent pastime that lives on through our televisions, computers and phone screens. Just think of the style of Instagram Reels where girls snap their fingers, or spin, in order to magically change their “fits” – a kind of playful dance of undersized and oversized modes of dress. Noticing the oscillation between small crop tops or miniature kilts and huge baggy sweatshirts on teenagers’ Instagram Reels, I can’t help but think of the anxieties of fit of Alice in Wonderland, which feels like such a girl’s trait.

When Carroll writes, “Down, down, down. Would the fall never come to an end?”, it feels like girlhood feels. But, like girlhood, Alice’s journey into the underground of Wonderland, or the mirrored world of the Looking Glass, are struggles of identity through which she eventually comes out. The magic of girlhood is, after all, its incoherence – it can be best understood as the trying on of different selves. As part of our collective imagination, Alice is now as far away from her Victorian context as she could possibly be: an emblem for the strength of will of all girls to escape one’s origins, as well as take flight from other people’s definitions.

Liddell, too, managed her own escape – just look at the photograph taken of her by Julia Margaret Cameron, also on view in Curiouser & Curiouser. Aged 20, here Liddell appears confident and self-assured: poised to become an artist in her own right.

Alice: Curiouser and Curiouser is at the V&A from 22 May 2021.