The first ever Hong Kong Film Festival UK presents an array of vibrant cinematic perspectives on “Hong Kong’s time of upheaval”

In the 1980s, Hong Kong’s film industry was so renowned that it became widely referred to as the “Hollywood of the East” – a source of tense crime flicks, martial fantasies, melodrama and violent exploitation movies to rival even the big-budget works being made in the US. But by the mid-90s, those fortunes had begun to change as political anxiety swept the nation; the sovereignty of Hong Kong was officially transferred from the United Kingdom to the People’s Republic of China in 1997, and the legacy of this transition still hangs heavily over Hong Kong’s arts scene today.

It is no coincidence that the first-ever Hong Kong Film Festival UK takes place on the 25th anniversary of the 1997 handover of Hong Kong, and indeed, strong political themes line the majority of works in the festival’s programming. The 2019-2020 Hong Kong protests are a focus of many of the 16 films screening in London, Manchester, Bristol and Edinburgh in March and April under the title ‘Rupture and Rebirth – Perspectives from Hong Kong’s time of upheaval’. The festival itself, meanwhile, is organised by artists and culture sector workers who have relocated to the UK in self-exile following controversial legislature passed by the mainland.

But the aim of the festival is not only to screen films that are no longer permissible for exhibition in their homeland – but also to shine a light on Hong Kong’s enduring vibrancy and creativity in the field of filmmaking. Here, AnOther takes a closer look at five standout narrative features, documentaries and short films from the Hong Kong Film Festival UK.

Revolution of our Times (Kiwi Chow, 2021)

In accordance with the “one country, two systems” principle of the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration, Hong Kong’s capitalist system and infrastructure should have remained unchanged for a period of 50 years after the handover in 1997. In 2017, the Chinese Foreign Ministry announced that the Declaration no longer had any practical significance, and in 2019 the proposed Hong Kong extradition bill suggested that people facing criminal charges could be extradited to the mainland to stand trial – a perceived erosion of the 1984 agreement.

This was one of the major catalysts that inspired the large-scale pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong that dominated the international news prior to the pandemic. With up to two million Hongkongers campaigning for liberty in a series of increasingly unstable conflicts in 2019 and 2020, the mainland’s response was to pass the 2020 national security law – criminalising acts of secession and subversion and making them punishable with a maximum sentence of life in prison.

These events are the backdrop and the focus of Revolution of Our Times, an epic and unflinching documentary comprising interviews, archival news footage and front line video recordings that give full context to the upheaval, as seen through the eyes of those at the heart of it. The images within resonate strongly – from the mobilisation of the masses against dubious peace-keeping forces to depictions of police brutality via truncheons, tear gas and rubber bullets, countless scenes in Revolution of Our Times mirror those that have shocked the world before and since the protests. The result is a powerful document that is not only essential to understanding the plight of the Hong Kong people, but also the tensions of the wider world today.

Banned from exhibition in China and Hong Kong, Revolution of Our Times will arrive in the UK as the Opening Gala of the first Hong Kong Film Festival UK following its premiere at Cannes in 2021, where it will be accompanied by a live-streamed Q&A with self-exiled director Kiwi Chow. A second documentary screening at the festival titled Inside the Red Brick Wall, meanwhile, focuses on the 16-day siege of the Hong Kong Polytechnic University – an event that forms the major focus of Revolution of Our Times’ penultimate chapter, and which resulted in the arrest of over 1,100 protesters in real life.

The Night (Tsai Ming-liang, 2021)

As insinuated by the title of this Tsai Ming-liang short film, The Night almost feels like a companion piece to the director’s 2020 Berlin Golden Bear-nominated feature Days – at least on the surface. Stylistically similar also to his great slow cinema masterpiece Goodbye, Dragon Inn, the Malaysia-born, Taiwan-based filmmaker’s newest documentary short consists of little more than ten fixed shots observing points of interest around a Hong Kong traffic intersection at night. There are no human subjects of note, nor even any dialogue – but what director Tsai communicates with these rich images somehow feels deeply profound.

The Night opens with a close-up of the remnants of old posters layered on an exterior wall – though what they were advertising is no longer recognisable. Next, a bus station is observed for a full six minutes – ample time to consider the painted-over graffiti as cars rush past from left to right. Later, a line of people forms at the roadside beneath the flashing blue neon of ‘Jubilant Medicine Shop’, before the cold metal of the interior of a deserted footbridge is lit with harsh white lights. The montage ends with an audio excerpt from the Chinese song ‘Liang Ye Bu Neng Liu’: “The beautiful night is slipping away. Why can’t we stop the hands of time?’

“One night, I began filming the streetscape of Causeway Bay after the frenzy subsided,” Tsai explains of the film (which screens as part of the shorts compilation ‘Multiple Realities’) in a statement published on the Hong Kong Film Festival UK website.“Witnessing the unexpected changes in the Pearl of the East,” he says, “I could not help but feel an emotional stir.”

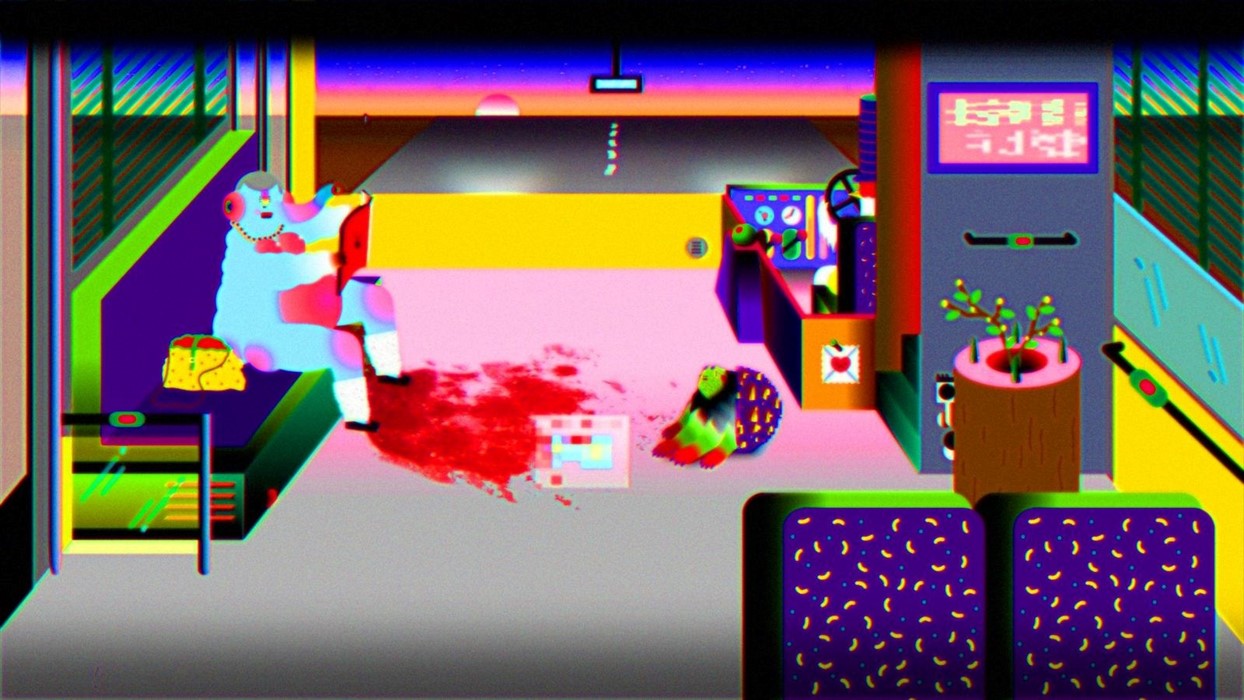

Wong Ping’s Fables 1 (Wong Ping, 2018)

Londoners might recognise the phantasmagoric digital media of Wong Ping from exhibitions like Strange Days: Memories of the Future at The Store X in 2018, or Heart Digger at Camden Arts Centre in 2019. The work of this avant-garde artist and animator is easily recognisable for its hyper-lysergic, sexually explicit and/or surreal nature – and this short-form riff on Aesop’s fables is no different.

The opening chapter of Wong Ping’s Fables 1 concerns a blind, one-eyed elephant who practices Buddhism and is dating a turtle. Another tale concerns a chicken suffering from Tourettes who is also a social media sensation, who joins the police and solves a number of unsolved cases. No less absurd is the story of a tree riding a kaleidoscopic bus who attempts to communicate with a cockroach in a passenger’s bag via telepathy.

These brief tales amount to what feels like a hallucination from the early days of the internet as recalled by a Skittles-coloured iMac. Throw in a load of grotesque anamorphic characters with wiggling appendages – plus a bed of audio that mixes chiptune SFX with the sounds of squelching flesh – and you’ve got Hong Kong’s most exciting contemporary digital artist.

Made In Hong Kong (Fruit Chan, 1997)

Anxiety over Hong Kong’s future was widespread in the years prior to 1997, with leading native filmmakers such as Wong Kar-wai and John Woo notably heading abroad during this period for fears of stifled creative liberties and diminished work opportunities at home. In the midst of such turbulence, Fruit Chan’s Made In Hong Kong would make a splash – it took home three Hong Kong Film Awards in 1998, including Best Film and Best Director, despite being completed on a budget of just HK$500,000.

This was the country’s first independent film of the handover era; an anarchic coming-of-age crime story set in Hong Kong’s densely populated housing projects, of a young Hong Kong hoodlum trying to find his place within the city-state’s vast urban sprawl. This AnOther feature on the crime cinema renaissance of post-handover Hong Kong explores the film in greater detail – but be assured, this isn’t merely a creatively and politically significant narrative feature, it’s a classic of contemporary Hong Kong filmmaking. Catch a rare UK screening of the recently-restored film at the Genesis Cinema in London on March 25.

Drifting (Jun Li, 2021)

One of the best films to come out of Hong Kong in 2021 was Jun Li’s second feature Drifting – a narrative work set in the predominantly poor district of Sham Shui Po in Kowloon, which is notable for being the target of a series of recent urban redevelopment projects.

Li’s film, which is based on a real court case that took place in 2012, explores the struggles of a community of homeless people living in makeshift homes beneath a flyover – who press charges against the authorities after they are forcibly evicted from their settlement, and their belongings are seized and destroyed. 1999 Golden Horse Film Festival Best Actor award recipient Francis Ng (The Mission; Exiled) delivers an emphatic turn as the film’s lead: a drug-addicted former felon dismissed as a vagrant by the police, but who displays remarkable compassion for his own beleaguered community.

The film awaits the results of eleven Hong Kong Film Awards nominations in 2022 – including Best Picture, Best Director (Jun Li), and Best Actor (Francis Ng) – which will be revealed on April 17. In London, the film screens at Picturehouse Central and at the Bethnal Green Genesis – with a pre-recorded Q&A with Li accompanying each screening.