James Balmont shares five outstanding highlights from the inaugural Odyssey film festival – a month-long celebration of China’s most “exciting and mysterious” cinema

While the Academy Awards have become visibly more cosmopolitan in recent years, and streaming platforms are bringing international films to Western audiences at a greater rate than ever, few could argue that the US still remains at the centre of global film discourse. It might be a surprise, then, to learn that greater China (including Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan) has in fact been the home to the largest film industry in the world for two years now – with over $7.4 billion in box office receipts reported in 2021, and with nearly 85 per cent of it coming from domestic films.

The pool of Chinese films that hit commercial cinemas in the UK remains limited, and often superfluous: politically-charged war blockbuster The Battle of Lake Changjin screened across 25 cities in the UK in late 2021, having already raked in a staggering $881 million at home to become the highest-grossing title in the world that year. But a thriving market of independent and artistic works also exists beneath this glossy surface – and by uncovering these, the inaugural edition of Odyssey: A Chinese Cinema Season hopes to rectify the often misbalanced understandings of Chinese-language filmmaking.

The festival’s mission is to unearth “exciting and mysterious” cinema that goes beyond the general public’s understanding of what Chinese cinema can be. And in May-June 2022, this is achieved with a programme of over 40 features and shorts across six curated sections – screening in cinemas in London and Edinburgh as well as online, and partnered with discussion panels, Q&As and awards. These vital works explore a rich breadth of themes: queerness, political oppression, traditional culture, and a strand dedicated to ‘Women Through The Lens’ included. Amongst them are forgotten Cannes classics and underground cult films – as well as contemporary works pointing to a new generation of talent.

Ahead of the month-long event, which launches on 10 May, AnOther dives into five outstanding highlights from the inaugural event; the UK’s largest Chinese-language cinema film festival.

Hard Love, 2021

In an opening visual, a line of people crowd around umbrellas in a leafy public park in China. Upon every brolly, a flyer is pinned – each one a handwritten scrawl that lists the age, job, income and place of residence of a different person. These are adverts by women (and likely, their parents) who are looking for a male partner to elope with. As the compere at a speed dating event claims soon thereafter: in Beijing, there simply aren’t enough suitable men to go around.

What follows is an eye-opening fly-on-the-wall documentary that follows five women in five cities, each of whom holds a different reason for remaining single in a transitional world where many still hang on to traditional Chinese values pertaining to marriage and family. Among them, an ambitious, career-driven woman who has “better things to do” than to settle down with a man; a former rebel teen and musician whose values are at stark odds to those held by her parents; and a social media sensation and single mother raising a child who carries a health condition.

Some of the obstacles these women face are highly relatable (one complains that the dating app Tantan is full of men who just want sex), while others seem very foreign from the perspective of a Westerner. Either way, Hard Love offers a fascinating insight into the tension between tradition and modernity across China, with the female struggle placed front and centre. It’s all filmed in a delicate, observational style by the filmmaker Tracy Dong – a graduate of the renowned Beijing Film Academy, whose alumni include Venice Golden Lion winner Jia Zhangke and three-time Oscar nominee Zhang Yimou.

10 May 2022, Picturehouse Fulham, London, and Picturehouse Cameo, Edinburgh.

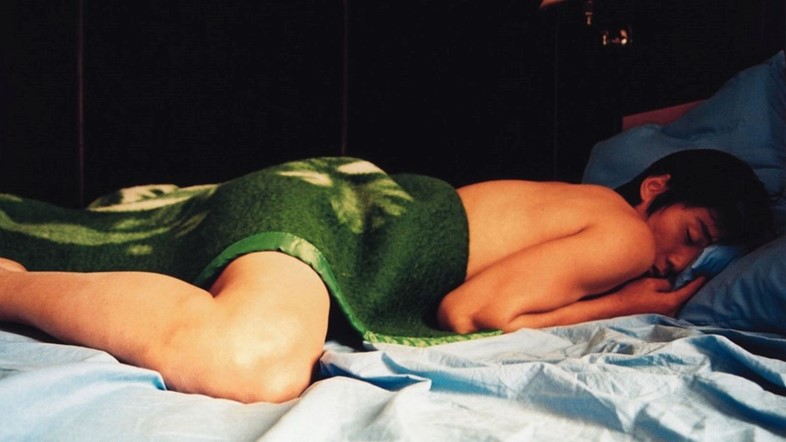

Lan Yu, 2001

Filmed without the permission of the Beijing government, and containing both direct references to the 1989 Tiananmen Square incident and scenes of simulated queer sex, Lan Yu was always fated for controversy. An adaption of a story published online by an anonymous tongzhi (“gay” person) in 1998, Stanley Kwan’s 2001 film was duly banned by the Mainland Chinese government upon release – though it received acclaim in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and at Cannes Film Festival.

At its heart, Lan Yu is the story of two male lovers: the titular Lan Yu (Liu Ye), a naive architecture student, and the closeted Chen Handong (Hu Jun), a wealthy and successful businessman. In a narrative that spans many years, this mismatched pair go through the motions – lust, love, betrayal and heartbreak – but with a pair of superb performances underpinning the brisk plot, their unsteady romance is captivating right up to the film’s unexpected conclusion. Equally vivid is the film’s rich aesthetic – built on vintage colours and meticulous set design, as well as a dainty, harp-based score that evokes the feeling of tip-toeing on a tightrope.

Director Kwan completed the film at an important time in his life. The Chinese auteur – a key figure of the Hong Kong Second Wave alongside the likes of Wong Kar-wai (In The Mood For Love) and Fruit Chan (Made In Hong Kong) – had come out publicly five years prior, becoming the first prominent queer filmmaker in the Chinese-speaking world.

12 May 2022, Prince Charles Cinema, London.

200 Cigarettes From Now, 2021

Speaking of Wong Kar-wai, Tianyu Ma’s 45-minute film 200 Cigarettes From Now – a highlight of Odyssey’s online ‘An Exploration’ short films programme – harks back to the delirious hedonism of Chungking Express, in a glorious snapshot of youth, love and liberty set in a tiny apartment in the city.

The protagonist, Xia, harbours feelings for a man who seems to have fallen off the face of the earth; she moves to Boston, where she makes ends meet writing scripts for a web series while her flatmate enjoys loud sex in the room next door. She sleeps in the living room beneath a disco ball, among scattered cigarettes and empty bottles of liquor; “I hear that every time you open a packet of cigarettes, you take one and make a wish,” she says.

This ultra-stylish short is built on a hyperactive visual style reminiscent of classic MTV, with neon lights and pop songs spun together in a montage of jagged editing and shakycam. The opening disclaimer – “based on more than one short story” – rings true for anyone who’s woken up on the floor the morning after a party.

Available online from 10 May 2022.

Summer Swing, 2020

In 1983, reads the opening titles of this 21-minute short film, the Chinese government announced a new crime-deterrent policy that decreed that breakers of the law would be subjected to “severe punishment”. Many forms of entertainment, it continues, were banned outright at the time – with dancing “regarded as hooliganism, and … sentenced [as a] felony.”

This oppressive backdrop hangs heavily over Summer Swing – the story of a teenage boy named Xiao Jun who works as a caretaker for a largely abandoned building complex. The film is near-silent at the opening as he wanders its dark, empty corridors at the opening – but soon, the sound of an ecstatic 80s pop song playing on a stereo lures him in as he discovers that a gang from his school has been organising illegal dance parties in his workplace.

With its warm, pastel colours, intricate set design, nuanced shot framing and themes of youth, repression and liberation, Summer Swing offers a stunning homage Edward Yang’s masterwork A Brighter Summer Day – a tribute underlined by the inclusion of a melancholy rendition of Rosie and the Originals’ Angel Baby at the short’s tragic climax.

Available online from 10 May 2022.

Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains, 2019

There’s an incredible widescreen tracking shot that takes place at about 45 minutes into this film. A young man dips into a jade-green river, and slowly swims past a succession of waterside pagodas and green willow trees; he emerges on the bank, and continues along the shore, deep in conversation with a woman, his love interest. This rich, slow-panning sequence lasts for a full ten minutes without a single cut, mimicking the fashion in which a painter’s scroll would be observed piece-by-piece as it is slowly unrolled.

Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains, the gentle, 150-minute, Camera d’Or-nominated debut of independent filmmaker Gu Xiaogang, takes its name from such a relic. The original is a sweeping wash painting of the lush mountainside scenery in Fuyang, Hangzho – one of the last surviving masterpieces of the 14th-century Chinese painter Huang Gongwang. Gu’s film – shot over two years and visually reminiscent of the works of Taiwan New Wave icons Edward Yang and Hou Hsiao-hsien – captures this, too, alongside a sumptuous medley of thriving marketplaces, 300-year-old Camphor trees, fishing boats sailing through fog and snowfall across a great river.

The film opens with a celebration: a birthday party for a 70-year-old woman, who falls ill just as the fireworks are ignited in the neon-lit streets outside a family banquet in a countryside town. Thereafter, we follow different members of her family as they embark on their own small journeys, address personal dilemmas and trade duties in caring for one another. The languid pace is meditative, but the cinematography is never not enchanting.