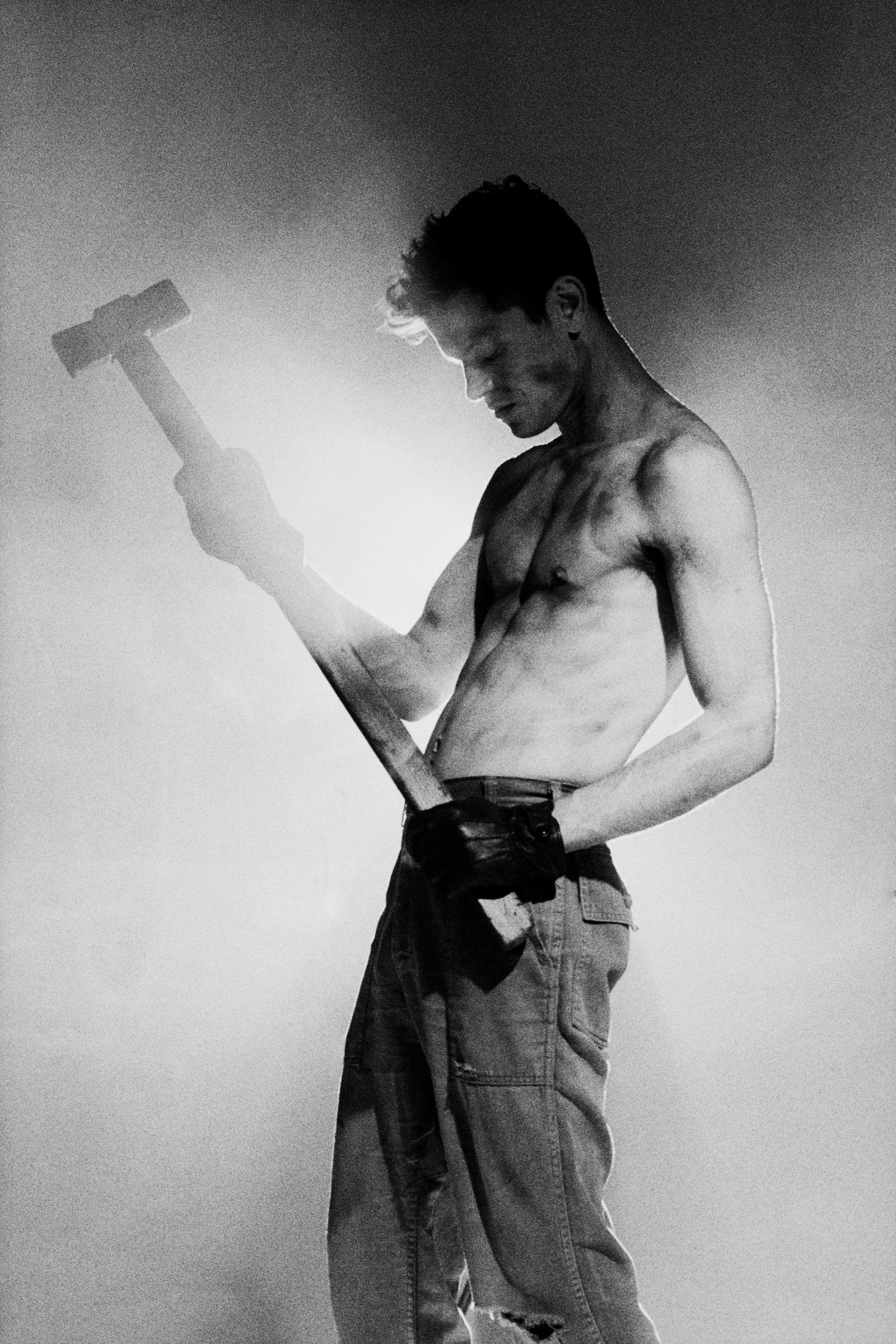

A naked man sits cross-legged, with two figures beside him, swabbing him with paint brushes and gradually revealing a phantasmagoric dreamworld lying beneath his skin. All set against Michael Hadreas’s distinctive falsetto croon, this is the opening scene of Ugly Season, a short film collaboration between Perfume Genius and visual artist Jacolby Satterwhite. It feels redemptive, a little sinister and, were it not so meticulously crafted, like the kind of thing you might see if you closed your eyes after taking too much ketamine.

Ugly Season, Perfume Genius’s sixth EP, sees Hadreas move in a more abstract, ambient and instrumental direction. Alternately foreboding and ecstatic, it has been likened by several critics to Radiohead’s 2000 masterpiece Kid A. Hadreas originally wrote the album as the score for The Sun Still Burns Here, a contemporary dance piece by artist and choreographer Kate Wallich, which he also performed in and co-directed. In June this year, he collaborated with Satterwhite on the 28-minute-long visual accompaniment, which combines fantastical 3D landscapes, fetishgear, go-go dancing and religious iconography from chakras to evangelical megachurches.

Hadres and Satterwhite make for natural collaborators: not only are they two of the most interesting queer artists of their generation, their work shares a certain sensibility. It’s a kind of defiant fragility, or, in Satterwhite’s words, the sense of “flesh being flayed, spread apart and put back together gracefully and monstrously.” Working within the mediums of 3D animation, immersive installation, and virtual reality, Satterwhite’s work explores themes of queerness, the body, consumption, and the idea of utopia. The visual accompaniment to Ugly Season was the culmination of two years of conversations between Hadreas and Satterwhite, and deeply informed by their shared love of certain pop culture references, including David Lynch, Lana Del Rey, Madonna and 90s sitcom Family Matters. “Pop culture, for me, is this space that is simultaneously frivolous and happy, but with a lot of melancholia residing within. Trying to negotiate that is something that both Michael and I have in common,” says Satterwhite.

After the quiet intimacy of its opening, Ugly Season eventually explodes into a hallucinatory and expansive satire of American life. “There’s a portal that takes the viewer into the nuclear family and the domestic home, the capitalistic idea of the happy family that you see in sitcoms,” says Satterwhite – a fantasy turned on its head by the presence of queer men go-go dancing on the front lawn. The film ends on a note of healing, with the same figure from the opening frame being pieced back together again. It’s a transcendent, discomfiting, richly textured work, and probably like nothing you’ve ever seen before.

Here, Hadreas and Satterwhite discuss their collaboration, the significance of dance, the anti-LGBTQ+ backlash currently sweeping the US, and more.

James Greig: How did you meet one another and how did this collaboration come around?

Jacolby Satterwhite: A colleague and friend introduced us, then Mike and I had a call together during the height of lockdown, just getting to know each other. That dialogue proceeded throughout 2021. When he sent me the album I listened to it every day and let it get into my system.

For a full year, I was doing my own research and building these digital words that I create by collecting assets, doing research in different communities and having strangers make drawings for me. Over time, I found that Ugly Season and its lyrics were cosmically aligned with where I was conceptually. I was working on a project where I was commissioning strangers in Cleveland, Ohio to make drawings of their visions of utopia. I felt like Ugly Season’s lyrics suggested a similar pathos, and that’s when everything began to gel.

Michael Hadreas: What was really inspiring to me about making the dance, which the music was written around, was that I was collaborating with people who I felt could understand where I wanted to go. When I started talking to Jacolby, I very quickly felt that same connection. We’re not trying to go to the exact same place, but we have some kind of similar kind of unspoken desires, and so it just made me really trust him.

“In a way, I kind of feel like I’m post-human, [because of my prosthetic shoulder] and I’m constantly negotiating with that psychologically” – Jacolby Satterwhite

JG: What do you admire about each other’s work?

MH: I could tell from watching and engaging with his [Jacolby’s] work that our connection was going to happen. There are certain ingredients: his work can be maximal in seven directions but it always has a lot of grace and harmony. That’s very satisfying, and that’s what I’m trying to reckon with in my own work – these big ideas and big feelings alongside smaller ideas and feelings.

JS: I agree. When I was working on the body of work that I was making between 2011 and 2014, I came across Mike's music, and watched and read a lot of his interviews. I just mined his work a long time ago, and I found such similar threads of thought. My work addresses issues with my body, my health, my lovers, my familial past psychology, and existential dread. I’ve never seen another artist oscillate between those things in the way that I do, but flesh being flayed, spread apart and put back together so gracefully, beautifully and monstrously is something that happens in Perfume Genius’s music – and it’s something that makes me feel like I’m okay. I think we both make very incongruent subject matters congruent.

JG: Dance and choreography play a central focus on this film. Why are you drawn to this medium

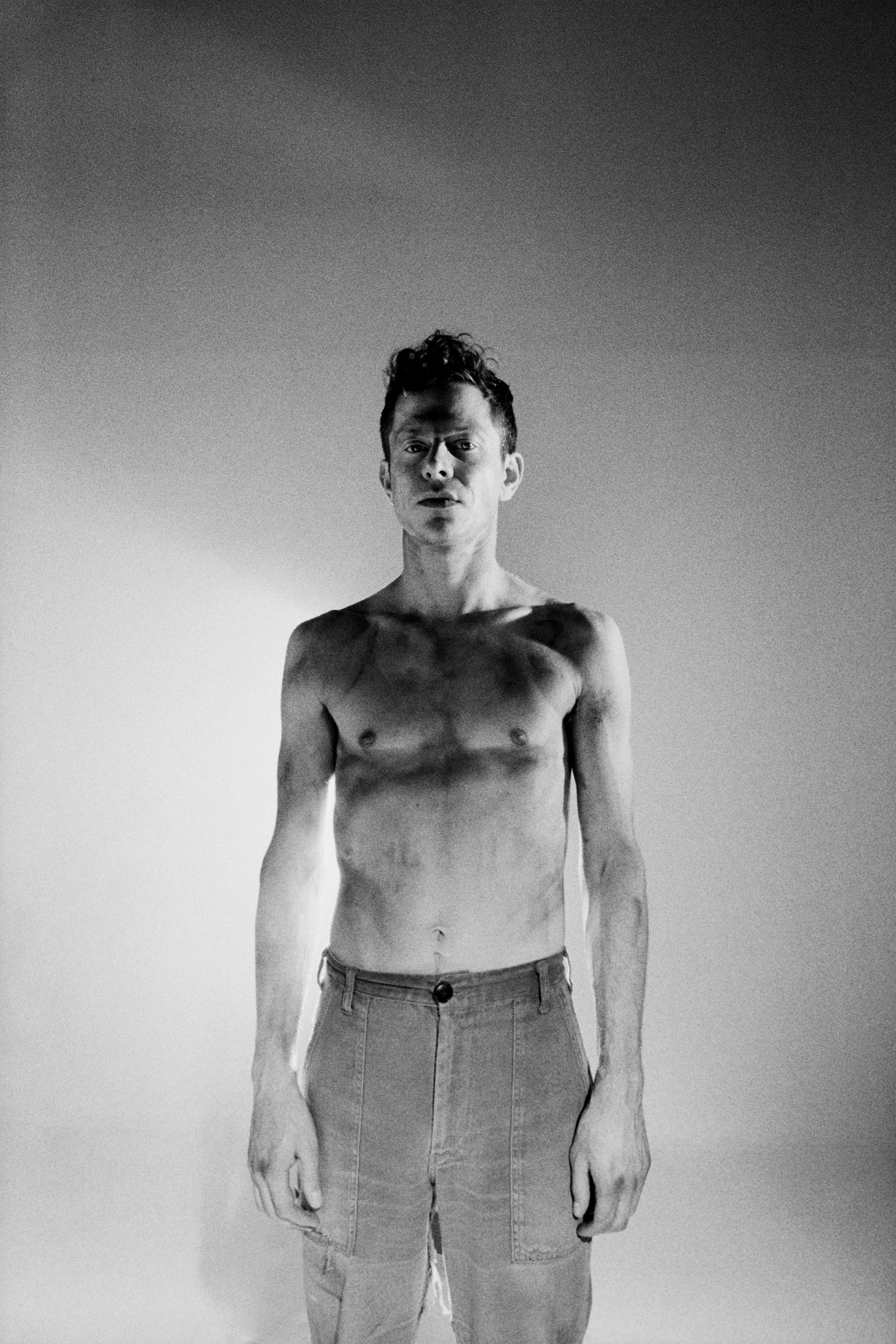

MH: I have a lot of issues with my body, but [while working on this project] I also felt really deeply connected to it, which is a strange place to be. When I first started performing, I didn’t really move at all, I was just sitting behind the piano, but over the years, I wanted to use it to communicate more. And it’s become a vital part of everything I do now.

JG: Do you think dance as a medium is able to convey things that other mediums can’t?

MH: Oh, for sure. Doing the actual dance performance and all the rehearsals for it wrecked me, because I’d never really been in a room full of people where I was just communicating physically. There’s a lot of really hippie stuff that I have ideas about, and I think a lot about transcendence. I have all kinds of ideas all the time, but I don't have a lot of feelings sometimes. And dance is a way for me to get those ideas into my body, and also to have entirely new ones that I wouldn’t have even thought of otherwise.

JS: Similarly, I have a lot of issues with my body. I have a prosthetic shoulder, because I had osteogenic sarcoma when I was a kid, which is a [type of] bone cancer. I have very limited movement and can only move my forearm. These limitations have really pivoted every decision in my life. When you work around your limitations, it creates innovation. My practice has always explored movement as an act of defiance.

In a way, I kind of feel like I’m post-human, [because of my prosthetic shoulder] and I’m constantly negotiating with that psychologically. My creations are a response to that, and I think that’s why I became a really ambitious digital animator and game maker, because that's the only way I can have complete agency over my craft as an artist When it comes to dance, I can be a heroic, dynamic and elastic figure with the power of my computer, my 3D animation, poetry, projections, and a camera. I can do so much of it with my art.

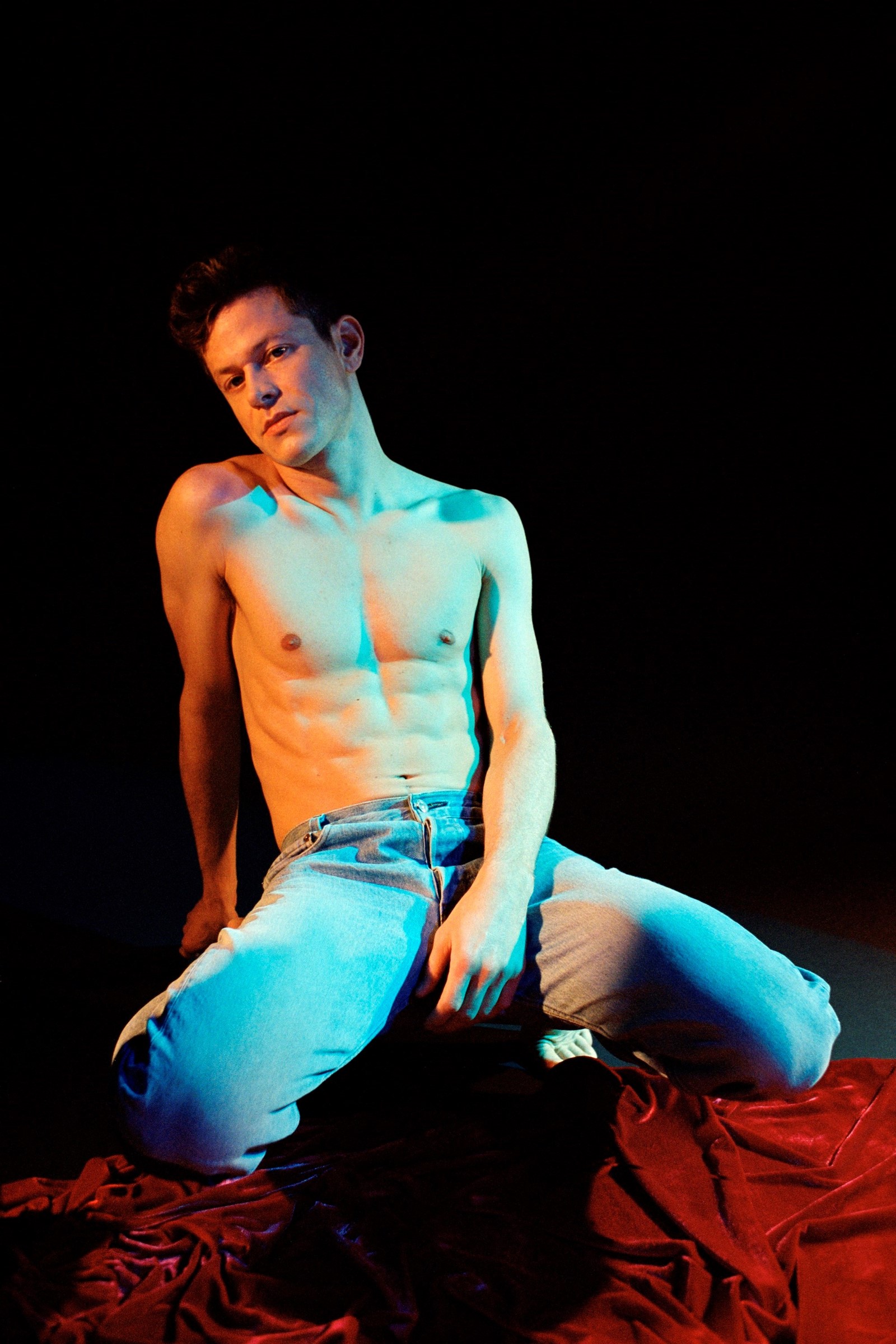

JG: I thought that a lot of the film is quite erotic or sexy, particualrly all the go-go dancers. Was that intentional?

JS: I am deeply embedded in radical fairy queer scene, and many of my friends are deep in the go-go scene. They’re really good at that, but they also study classical ballet and modern dance, and can play 15 different instruments. What’s so amazing about them is that they’re 3000% in charge of their sexuality, and they’re just very visceral and expressive people. That’s what my attention was with the casting: they are people who can heal the world, not only with their poetic, sonic and expressive energies, but also with their their sexual confidence. It liberates the people around them, and makes Brooklyn and Lower Manhattan a better place.

“I want to give young people permission to see themselves in the same way without having to posture as someone else” – Michael Hadreas

JG: There has been a big resurgence of anti-LGBTQ+ sentiment in the US recently. As queer artists, how do you feel about that?

JS: I grew up in the Deep South in a very conservative Christian family where none of this was permissible from day one. I had to reckon with shame and denial, and I had to unlearn a lot of that up until my thirties. So, I’m not too shocked.

But a lot of my work is about resisting and unpacking that and normalising my life. I’ve always been a force of resistance. So I don’t feel any different now, seeing things that were already obvious come to the forefront for people who probably thought things were a lot better than they are. I’ve never been an optimistic person.

MH: Me neither, I feel the same way. It’s just been part of it since the beginning. When I released Queen [Perfume Genius’s defiant, 2014 queer anthem], people were asking me all the time, ‘Why are you writing this? Do you think the world really needs this song?’ Because things were supposedly getting better.

JG: It’s depressing that Queen feels even more relevant now than it did in 2014.

MH: I think it does, yeah. People are emboldened now, but people have always been awful. Things have always been bad. But that doesn’t mean I’m not upset about this backwards movement.

JG: Do you think this anti-queer backlash will inform either of your work going forward?

MH: What’s hard is that whenever I try to intentionally come with that energy, it feels kind of preachy. I don’t want to be too indulgent So it's about finding this balance of: how do I talk about things that are important to me and come from a place that’s personal? But also, it’s really important to me that it’s helpful and something that I would have wanted to hear when I was in a dark place, or something that I wish I would hear from someone else right now. And I’ll try to do it myself, and mix all those things together. And I’m sure that that will be more in my mind next time I go to start writing.

JS: I agree with all that, when your work is speaking to your younger self and hoping that younger self exists in some generation. It’s really rewarding when you are working from a position where you know someone needs to see someone older existing in a certain way to give them agency and get them out of a dark place. My kind of body, with my kind of presentation, affect and accent, is rarely seen in a commercial and public domain. I want to give young people permission to see themselves in the same way without having to posture as someone else.

Ugly Season by Perfume Genius is out now.