Before I could start oestrogen I was asked if I wanted to freeze my sperm. My response was immediate. “No.” At a surgery consultation, I was asked once more. Caught off-guard, thinking my one-time answer would be the end of it, I again said no. No one pressed me but it was one of the few times in my life someone asked me directly if I wanted kids – perhaps the only time someone asked me if I wanted biological kids.

One day, perhaps soon, there will be uterine transplants for trans women. An attempt is already underway by a doctor in India. Cis women have now successfully had children after uterine transplants. Dr Jacques Balayla has written multiple papers arguing for the implementation of uterine transplants for trans women. Balayla believes it is “inevitable”, though he’s faced plenty of flack from the bioethics community and radical feminists around the world. So far it’s mostly the ethical implications that are being studied. Multiple surveys and interviews on the “reproductive aspirations” of trans women have been conducted. Uterine transplants have been primarily for short-term use. At the moment a uterine implant wouldn’t allow a trans woman to conceive naturally and IVF would be required since the womb would not connect to any fallopian tubes. Another requirement? Getting a C-section.

I can’t make it through most of the mum-lit canon. I try to read Rachel Cusk and Sheila Heti, but often the only thing I can hold onto is their wariness. What I do want is the option to have kids. I want the possibility looming. I want, like Reese in Detransition, Baby, the fear of being impregnated to hang over me.

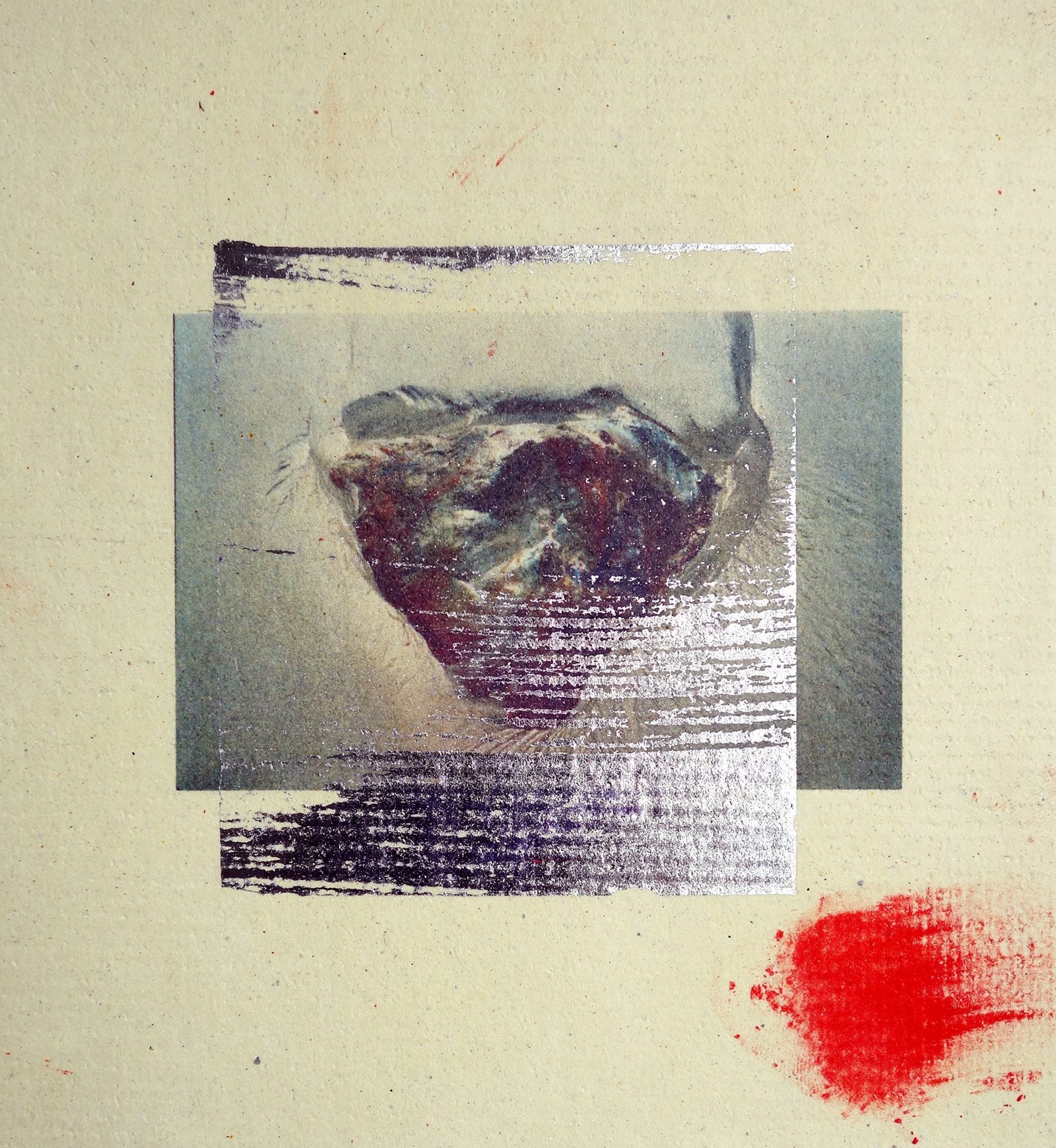

In Morgan Thomas’ excellent short story, Bump, Len, a trans woman dating a married cis man, wants to have a child. Len’s lover ends up having a child with his wife, a child which Len babysits and calls “the aphid”. She decides – in one of those surreal fever dreams – to buy a fake baby bump. She begins wearing the baby bump during her everyday life, passing as a pregnant cis woman. As the story winds down, Len has sex with her lover while wearing the baby bump. It’s heartbreaking. Afterwards, she crawls into bed with her grandmother, lonelier than before.

Lili Elbe was an early pioneer in this regard, receiving a womb transplant in 1931. Ebbe was often in contact with Magnus Hirschfeld, a researcher whose work was destroyed by the Nazis. Hirschfeld was a sexologist working with many queer and trans people to understand and systemize knowledge. Elbe died from complications from her womb transplant a few months later.

***

Here’s to all the MILFs I’ve loved before, all the times I told someone to impregnate me, to all the men I confessed I wasn’t sure I wanted to be a mother but I wanted to be able to have an abortion. That I wanted, in fact, for every woman to be able to have an abortion. This is not on the acceptable list of desires. My womanhood has never curved the correct way, even when I wanted it to. I can try to be an appropriate woman in turtlenecks and black dresses but I don’t make my bed every day. Disciplined as I am in some ways, I will never be able to cook a beautiful meal for a boy every night. But I can imagine myself in line at the clinic getting the pill or tested for STDs.

It’s not that I’m reckless or that I’ve never considered being a mum. It’s merely that my life has been a narrative filled with small failures. The failure to be included in a group chat. The failure to be good at partying. The failure to find a hobby. Desire wraps itself neatly around me like a yoke.

I didn’t want to write about desiring motherhood for so long because I didn’t want to find out if I really wanted it. I ask the trans women I know who have kids about their attempts at breastfeeding, about their relationship to motherhood, about school pickups among throngs of cis women. One night outside of a bar, I played airplane with my friend’s kids, gently launching them up in the air and back down again as they giggled. I saw my reflection smiling in the window.

I often think of the scene in Sex and the City where Carrie debates whether a man is worth giving up the possibility of having a child. She was asking the now classic question: how much can a woman want before her house of cards comes toppling down? How much is included in “having it all” before we’re had by the cruelty of desire? I worry I’m only kidding myself.

In my case, no one was asking me to give it up. But no one was asking me to have a child either. I sat in Prospect Park as my friend told me I would be a good mother. We took the train to Coney Island and I watched the waves in the cool wind of September. My friend wandered off to get us cotton candy. In a thin blue dress I thought about the people who told me they wanted kids, just not with me.

Later we stopped in a bookstore and I saw a card that said “Motherhood looks good on you.”

***

In her watershed essay Mothers, Jacqueline Rose writes that “[t]here was a time when becoming a mother could signal a woman’s entry into civic life. In ancient Greece, a woman was maiden, bride and then, after childbirth, mature female, which allowed her to enter the community of women and participate in religious ceremonies.”

As a society, we haven’t moved that far away from this idea. Now tradwives and cottage-core acolytes find meaning in cramped lives at home, giving birth, and preparing meals for their husbands.

The fear that cis women face over creation is different. I’m not sure trans women are expected (much less wanted) to participate in the public sphere. The past few years have made that hellishly clear.

A filmmaker I used to work for had a child not long before we started working on a project together. During filming, the child and their mother wandered around Brooklyn or sat in front of a fan in their apartment. The filmmaker and I worked eight 13-hour days in a row. One day we met up with a famous artist who informed us she was planning to have a child with her partner. I wondered if that future awaited me, thinking of my ‘partner’ at the time, a man who yelled at me on the phone from hundreds of miles away and would not tell me how old he was. I suddenly felt like a child.

Three years later, I sat on the grass outside a sound studio while working as a driver for the same filmmaker. My job for the afternoon was to pick up his spouse and child from the hotel and bring them to set. A few other people I knew from previous projects were milling about in the waning dregs of the summer heat.

I asked about the child. I asked the others if they wanted kids. It had become a light obsession. They turned it back on me.

“Do you want kids?”

“If someone else really wanted one,” I said, picking at the grass.

***

I don’t know if I would elect to get a womb transplant once they become available. That feels like an impossible longing to place. Instead, I turn towards the trans women mothers who provide a messy network of care and mentorship, often coaxing us away from the disempowerment of cruelly optimistic tradwife fantasies and into less well-known corridors of embodiment. Towards the end of Mothers, Jacquline Rose summons transgender theorist Susan Stryker’s famous essay My Words to Victor Frankenstein Above the Village of Chamounix. Stryker ponders the monstrous body of the transsexual, its rage, its joy, its endless entanglement. But she also narrates her lover giving birth, feeling the skin of her lover’s back and the “dark, unsolicited feelings [that] emerge wordlessly”.

A little over a year ago my boyfriend drew me close as we laid in their bed and their black cat sat on my feet. “A little family, my girls,” they said. Something beyond the language of motherhood shimmered up my spine.