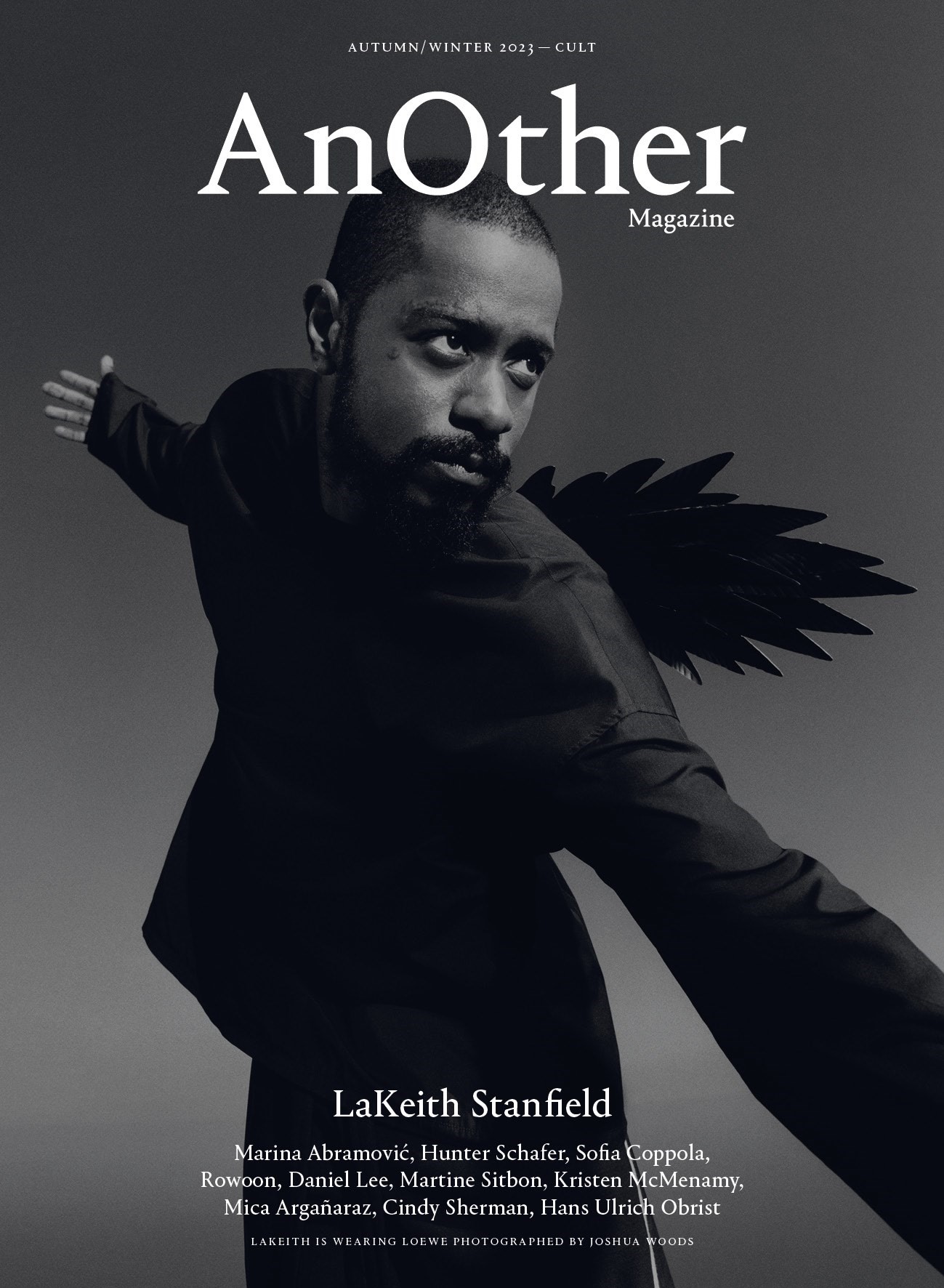

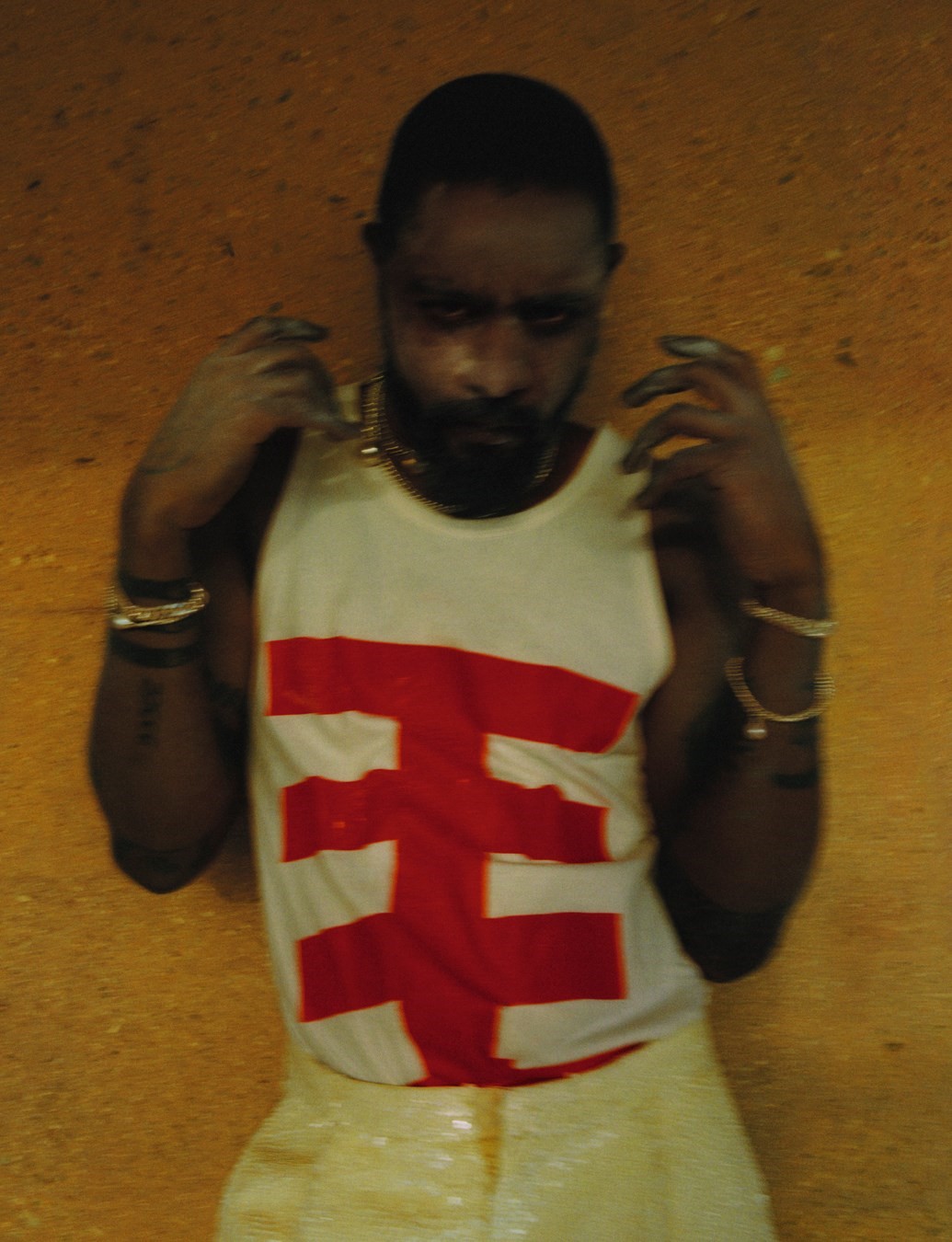

This project is taken from the Autumn/Winter 2023 issue of AnOther Magazine and was realised before the SAG-AFTRA strike was announced:

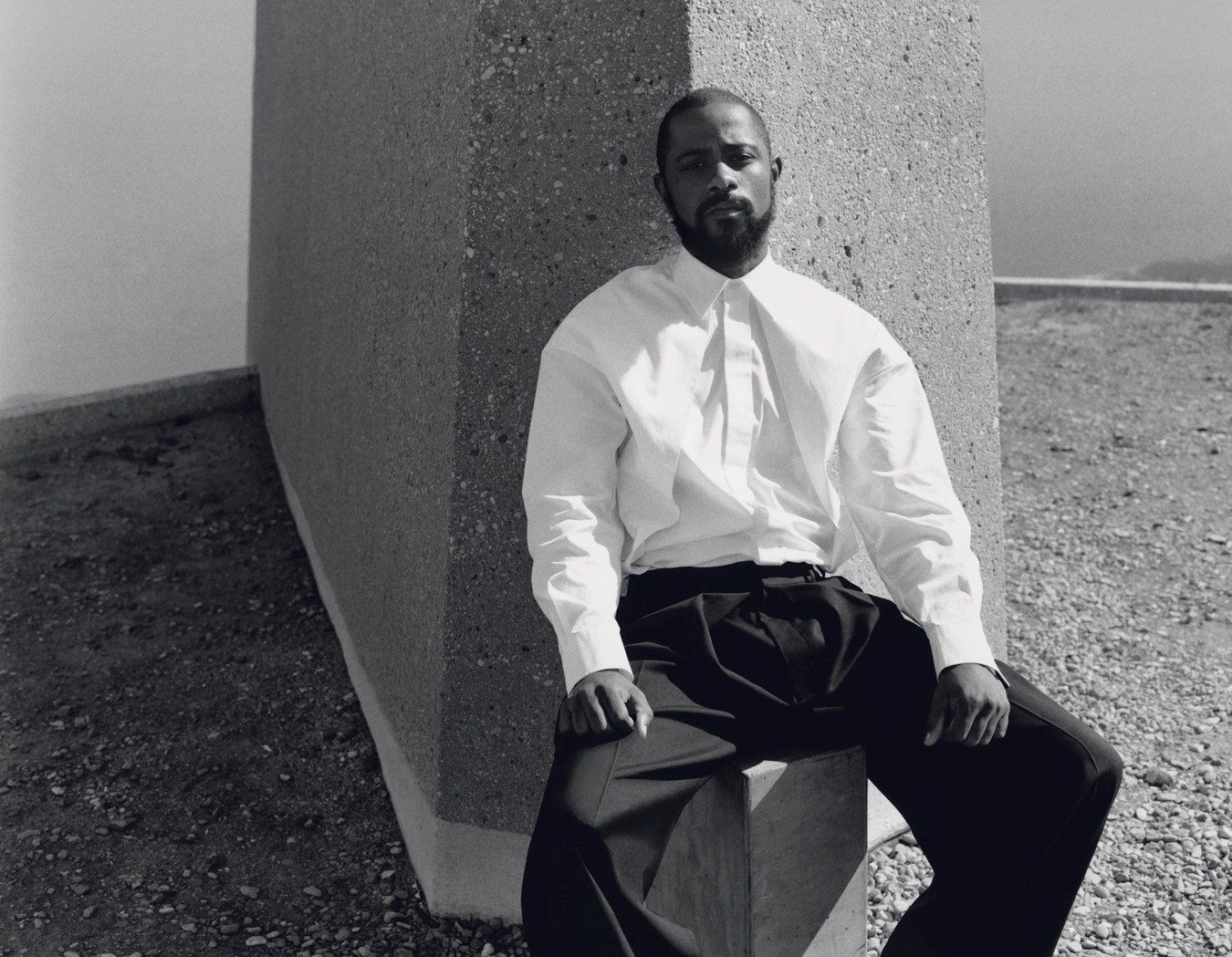

It’s two hours past call time and LaKeith Stanfield still hasn’t shown up for the cover shoot. His absence has engendered a slightly anxious mood on set. Walkie-talkies crackle. The crew paces back and forth under the hot sun. Rattlesnakes forage in the dry chaparral. Everyone seems a little on edge and, geographically speaking, they are. From 2,000 feet above Malibu, perched at the summit of the dry hill-scape, the sky out over the city blends seamlessly with the Pacific Ocean, to the point where it’s difficult to tell one from the other in the vast expanse of blue. There is the sense that you’ve arrived at the world’s outer limit – or at least the end of California. It doesn’t seem irrational to wonder if, by now, Stanfield has grown tired of the weathering demands of celebrity: the endless procession of reporters, the fans interrupting dinners with weed offerings or impressions of his characters, the ambient expectation that he should always be available to entertain.

The truth is that Stanfield hasn’t been outside the public’s sphere of attention since he found his way into it ten years ago, as a 21-year-old off-the-radar newcomer from San Bernardino, California, who didn’t own a cell phone and had been most recently employed at a weed grow house. His first role was that of an emotionally volatile kid about to age out of a group home for at-risk teens, in a thesis film-turned-small budget feature called Short Term 12. Theories abound that the movie is charmed; its lead actors Rami Malek and Brie Larson are big names now. But it was Stanfield, playing Marcus, who left the most lasting impression. He dissolves into his characters; sometimes it seems more like he’s transcribing his own moods than reciting lines. The wounded sensitivity he brought to the role was so internalised that, when Marcus burst into tears after shaving his head and finding no scars left over from his mother’s abuse, Larson “had to excuse myself from the scene and cry”. The breakdown hadn’t been in the script.

Back at the motorhome at the base of the hill, Stanfield is dressed as himself, in a pale green knitted polo, black jeans, a black baseball cap and socked feet slipped into Birkenstocks. Thick, arcane symbols are tattooed along his hands and arms like doodles scrawled into a high school notebook. He’s stretched out on a couch that lines the back wall, his posture easy and relaxed. It’s hard to say whether the four hours of shooting under the hot California sun has drained his sociability, because there is a perpetual air of almost monastic tranquillity about him, a natural orientation that could easily be misattributed to the composure of perma-friedness. He denies my offer of Reese’s Pieces in favour of a transparent container filled with large slices of dried mango, which he picks at while we talk. “Poisoning yourself makes you do things you don’t want to,” he says in response to a question about spirituality, which sounds more like the reasoning behind his sobriety. “You start to become the things you ingest, so you want to stay away from things that can damage your body.”

Stanfield is currently on double-promotion duty for films that could not seem more distinct (this interview took place before Sag-Aftra announced strikes on 14 July 2023): a Disney remake of 2003’s The Haunted Mansion, in which he plays an expert hired to evacuate ghosts from a decrepit property, and Jeymes Samuel’s enigmatic The Book of Clarence, which is due out in January. What is known about the latter is as follows: (1) it takes place in 29 AD Jerusalem, but was filmed in Matera, the same southern Italian town where Pasolini shot The Gospel According to St Matthew; (2) Stanfield plays the titular cult leader, who is “looking to capitalise on the rise of celebrity” and “influence the Messiah for his own personal gain”; and (3) camels shit so frequently and profusely that there were workers whose sole job on set was to clean up after them. “Peace to all the gods that allow these people to be so great at what they do,” Stanfield says. “But, like, bless them. I know that’s a stinky job.”

“I always wanted to be the centre of attention” – LaKeith Stanfield

Stanfield previously worked with Samuel on 2021’s The Harder They Fall, a high-octane, orgiastic bloodbath of a film that everyone called “revisionist” because it inserted Black people into the western epic tradition – never mind that the whole master narrative of John Wayne types as the heroes of the Old West is itself a romantic construct. Samuel’s film instead took up a playful, winking disinterest in the trappings of historical accuracy. He laundered the real stories of 19th-century Black cowboys through his Blaxploitation-conscious sensibility, and metaphorically killed Tarantino when he shot the first white person who fixed their mouth to say the n-word. He intentionally undermined the time period with an anachronistic soundtrack, smuggling Jay-Z, Lauryn Hill and Barrington Levy into the 1870s. “Jeymes just knows how to create these special environments that are unlike any other film sets you’ve ever been on,” he says of the director. “You go on his sets and there are these giant speakers playing music, and everybody’s dancing and it’s like a party. It’s all these Black people, and we’re all having organic fun. And so, when we get on screen, that transition is seamless. The fun you see is real.”

It seems like he’s having a blast in The Harder They Fall. In a cast of otherwise serious, quick-tempered characters, Stanfield’s interpretation of Cherokee Bill (whose infamous last words before he was hanged were, “I came here to die, not make a speech”) is calm, reluctant, humorous. He doesn’t want to use violence. He’s an outlaw with a bountiful kill record who seems bored by his lack of competition, an arrogant, western One-Punch Man with a haunted stare and perfect comic timing. It’s often Stanfield’s comic instincts – his eccentricity, his unsettled physicality, his nonchalant delivery of utterly absurd lines – that make him a reliable scene-stealer, alternately magnetic and memorable even among an ensemble cast of seasoned performers. That In Living Color and Saturday Night Live were his favourite programmes growing up tracks. Consider, for example, an unscripted moment from Atlanta, when his character, Darius, is cleaning his gun and lovingly refers to it (him?) as “Daddy”. “You call your gun Daddy?” says Paper Boi, hilariously played by Brian Tyree Henry. “That’s weird, man.” They go back and forth like this, bantering over the sexual implications of the word before Darius pauses, then suggests, softly: “You not gonna see this, but your assumed perversion of the word Daddy? I think that’s stemming from the fear of mortality, man.” What?

Stanfield had odd dreams while he was away filming Clarence in Matera, dreams where he was trapped in a stone dimension not unlike the dark, yawning grottos scooped out of the calcareous rock all over the prehistoric city. He describes feeling isolated while he was there, a condition exacerbated by personal issues he alludes to but does not elaborate on. “Sometimes you’ll get these roles and they’ll mirror you, or you’ll mirror them, and it feels like you’re literally going through the same thing,” he says. “I was going through some hard stuff while I was filming, and I would often ask myself, like, ‘What would Clarence do?’ It was really strange. I’ve never really done that with a character.” Whether or not a cult leader would make for a trustworthy spiritual guide remains inconclusive.

Stanfield was raised in Riverside, near San Bernardino, and later in Victorville, out in the Mojave Desert. He came of age in a barren landscape known mostly as a set piece for Lethal Weapon and Kill Bill: Volume II, but also for the nickname it was graced with by the people who live there: Victimville. The seventh top employer when Stanfield lived there was the Victorville Federal Correctional Complex, a dark mass of grey watchtowers, double electric fences and squat concrete buildings spread out over 1.2 million square feet of the Mojave.

It’s unclear whether the nickname Victimville was intended to reference the 4,000 inmates housed in those prisons or to describe the culture of violence and poverty in the region. Stanfield occasionally got into trouble while living there, got in fist fights over girls or stole sandwiches and bottles of beer and got Tasered for smoking weed and learnt the hard way – or so he told Complex magazine in 2016 – that “you can’t really outrun a helicopter”. But on the whole, his life in Victorville was far less violent than it had been in Riverside, where he sometimes witnessed his mother’s boyfriend beating her up. And so he decided that it was a kind of haven. It was sleepy. Not much to do.

The boredom forced his imagination. “I always wanted to be the centre of attention,” Stanfield says. He was the designated entertainer of the family, the one who would stage sock puppet shows and feign accents at gatherings, who would slip into his aunt’s church wigs and then dance around the living room, pretending to be someone else. His bedroom walls were papered with sketches, poems and symbols, and there was a makeshift recording booth made from egg cartons. He watched Love Jones, Menace II Society, Boyz n the Hood, Brown Sugar – then wandered the flat desert plains and allowed his mind to compose its own characters, with their own specific micro-dramas. “I was completely apathetic towards school,” he says, and he flunked nearly every class except for drama. When he was 15, he started googling any terms he could think of related to acting and signed up to whatever materialised online and sent off his information to random email addresses in the hopes of landing an audition.

“I think there has just been a fire lit under me ever since the opportunity to be a performer first arrived in front of me. And I haven’t looked back. I have to take advantage of every opportunity I get so that I can continue to do this work. So I’m always going to throw everything at it. My ambition hasn’t waned” – LaKeith Stanfield

The first response he got wasn’t for a part in a play or film, but for a slot at a school called the John Casablancas Modeling & Career Center, which was founded by the same man who launched Elite Models and cost $5,000 to attend sessions for. Eventually he landed the Short Term 12 role – and though Destin Daniel Cretton’s short premiered in 2009 at Sundance and won a jury award, nothing really came after that. Stanfield’s inbox stayed empty and nobody came knocking at his door. He moved to Sacramento to develop a relationship with his father and worked as a lawn mower, a door-to-door salesman for AT&T and a weed salesman at a grow house. The day he was fired from the AT&T job for childhood run-ins with the law he checked his inbox and found five consecutive emails from Cretton, who said he was adapting the short into a feature and was hoping Stanfield would audition to reprise his role. (He was the only cast member carried over from the short and ended up with a best supporting actor nomination at 2014’s Independent Spirit Awards, as well as a nod from the Satellite Awards for a rap song he wrote with the director.)

In 2014 alone, the year after Short Term 12 came out, Stanfield appeared in Selma and The Purge: Anarchy, two big-budget studio movies that were smashes at the box office. The following year, he had credits in seven films. He released experimental rap songs as part of a band and, on his own, appeared in music videos for Run the Jewels and Jay-Z, danced drunk at a party, as if he was the only one in the room, and was hired on the spot to play Darius in Atlanta. He had all of two scenes in Get Out and nobody forgot them. He worked, and worked some more, and somehow managed to eke out a place for himself in Hollywood that doesn’t require a series of bargains and compromises, which gives him the latitude to play an unusual set of characters who reflect the expansiveness he sees in his own humanity. When I ask him why he works so often, what might happen if he finally decides to be still – on top of Clarence and Haunted Mansion, he’s also starring in a new Apple TV+ series called The Changeling – he pauses.

“I think there has just been a fire lit under me ever since the opportunity to be a performer first arrived in front of me,” he says. “And I haven’t looked back. I have to take advantage of every opportunity I get so that I can continue to do this work. So I’m always going to throw everything at it. My ambition hasn’t waned.” He has always understood that the line between having and not having is tenuous.

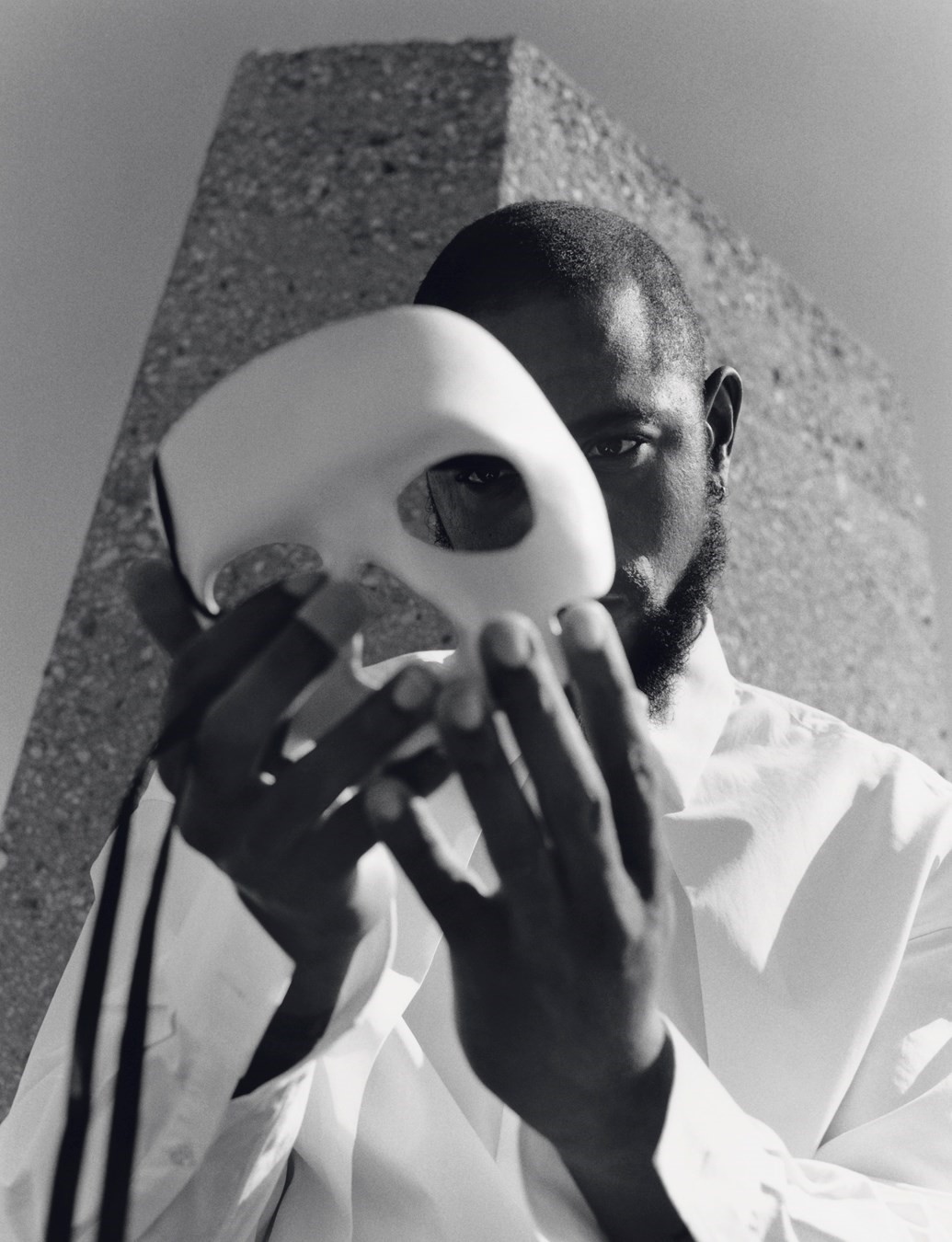

“It’s really hard, maybe even impossible to maintain a perfect centre all the time,” Stanfield says. I’ve just finished telling him a story about my aunt, a stage actress known as the “first lady of Jamaican theatre”, who would sometimes, in my mother’s words, “bring her characters home with her”. How she would come home attended by a shroud of misery, moving through the house as though behind a veil of cellophane. It seems to resonate. Stanfield makes himself blank when accommodating a new character, and then excavates from his own old wounds and past experiences to fill out the psychic space. The goal is to achieve a state where one is not performing so much as being. His characters become portals through which he can explore the inner lives of other people and also a mirror within which he can more clearly evaluate himself. “If you’re paying attention, and if you’re lucky enough to come across a role that was written well, you’ll typically learn something about yourself or a version of life you haven’t had,” he says. “And those can be positive lessons. Or not. It doesn’t always feel good.”

Stanfield doesn’t call it method, but his immersion can still be destabilising. Anecdotes that could pass for mythology proliferate around his craft, his intensity, his dedication to the role; Hollywood loves a martyr, the high drama of suffering transmuted into art. For his scene in Selma when Jimmie Lee Jackson is beaten and shot to death by state troopers, Stanfield ran laps around the set so he would lose consciousness as the cameras started rolling, his eyes fluttering shut and his body shutting down. In Short Term 12, when his character whacks another boy with a wiffle-ball bat, the rage felt so real to Stanfield that he actually struck the other kid, whose father ran out to chastise him with a reminder that he’s supposed to be acting. And after wrapping Uncut Gems, Adam Sandler told its co-director Josh Safdie that “the only other actor he’d ever seen get that deeply into character was Dustin Hoffman”, who infamously antagonised Meryl Streep on the set of Kramer vs Kramer by slapping her across the face and taunting her with remarks about her recently dead boyfriend.

Of all the roles he’s played, something about Stanfield’s performance in Judas and the Black Messiah is outstanding – moving, sends shivers down the spine. He plays William O’Neal, the FBI informant who infiltrated the Black Panther Party in the late 1960s and provided the floor plan of Fred Hampton’s apartment that facilitated his assassination. For his part, O’Neal is a haunted, tragic figure; even after drugging Hampton the night before his murder, he begged the family to let him be a pallbearer at the funeral. Stanfield plays it all with a simmering neuroticism, every movement animated by an uncertain twitchiness, every spell of laughter reaching for a hysterical pitch. In the moments when the room is dense with fraternity and affection, we see him quietly tortured by the scale of his own betrayal, his posture suddenly resigned, his eyes tearful and dark, the weight of this double consciousness seizing his faculties. The only documents that Stanfield had to consult were court transcripts and a PBS documentary from 1990 called Eyes on the Prize II, in which O’Neal’s delusions are on uncomfortable display: he claims that at least nobody can call him an “armchair revolutionary” because he was actually “part of the struggle”. He killed himself the night the documentary aired, ran out onto Chicago’s Eisenhower Expressway and had his body crushed by traffic.

“You’re playing with your psyche, as an actor. That’s something that is sensitive. And if you’re a performer, chances are you’re sensitive, like me. So you have to be careful about some of the places you go. I learnt that the hard way” – LaKeith Stanfield

Stanfield was haunted by the part. He had panic attacks on set that sent him scurrying out of trailers and into the open air. Alopecia that had been in remission returned, inexplicably. His hands would shake, then go numb. He couldn’t straighten out the ethics of bringing sensitivity and understanding to a man who had acted with such murderous self-interest, whose entire system of morality seemed at odds with Stanfield’s own. And a scene when he drugs Hampton, which didn’t make it to the final cut, felt somehow real to him. His body couldn’t differentiate between the role and the reality – something his co-star Dominique Fishback had warned him of. “I didn’t know what was going on at the time, but I guess I was putting myself under a lot of stress,” he says. “There aren’t really too many apparatuses in place to help artists deal with the aftermath after putting their all into these things. So you have to take the responsibility upon yourself to try to figure out what that means. And since I’m not super-religious, I had to find a way to help me in those moments.”

He ended up in therapy, which has since become a “spiritual parachute” that keeps him from going too far. “You have to be aware of how the things that you’re downloading affect you,” Stanfield says, “because you can sometimes go to places that, if you aren’t careful, can be hard to navigate and come back from. You’re playing with your psyche, as an actor. That’s something that is sensitive. And if you’re a performer, chances are you’re sensitive, like me. So you have to be careful about some of the places you go. I learnt that the hard way.”

LaKeith Stanfield is “Showing Hollywood How to be Weird”. Or is “the Greatest Weird Actor of Our Generation”. LaKeith Stanfield is “Reframing” Black masculinity, “Redefining” Black masculinity, “Revolutionising” Black masculinity – or anyway, he’s doing something that involves Blackness, weirdness, masculinity and Hollywood. The way critics write about how Stanfield fits into the tapestry of Hollywood’s leading men tends to focus on the perceived strangeness of the parts he chooses, how he’s presenting a contemporary vision of Black manhood that (some) people aren’t accustomed to seeing. The idea, however myopic, is that our Black movie stars are always possessed of an impenetrable cool, an easy-going charisma shared by Denzel Washington, Morgan Freeman, Samuel L Jackson, Sidney Poitier. Stanfield gravitates towards characters who could scarcely be described as “cool”. His men are offbeat, tense, unsure. Anxiety is common. And it’s clear he identifies with them in some capacity. It’s why he picks them.

But he doesn’t recognise himself in that sociological way that critics write about him. Probably it’s annoying to have a bunch of journalists, often white, repeatedly call you weird. There’s a way that people tend to conflate Stanfield with his roles, assuming there’s no significant distance between LaKeith Stanfield the person and, for example, Darius the character. This seems at least partially merited. Much of what Darius says on Atlanta, like the gun thing, is improvised. And, like Darius, Stanfield prefers a freewheeling conversation style involving unbroken eye contact and the occasional meditative, slightly off-kilter digression. After five series of the show, Darius is the part people most associate him with. “It’s been a long run with the Atlanta boys, and I’m so grateful to have been part of that,” he says, noting they’ve wrapped filming on the final season. “It was cool to play this character who sticks with so many people, someone they resonate with and who feels like a real person to them. So many people run up to me acting real goofy because they think I’m Darius.”

It could also be that he doesn’t seem to take fame particularly seriously. There was a time when he was suspended from Twitter for impersonating other celebrities, from Offset, Mo’Nique and Jack Black to Cardi B and Donald Trump. In 2018, having already acted in enough films to be considered famous, he posted his real phone number online. He showed up to interviews on his press tour for Death Note as his eccentric detective character, L, crouching in chairs and saying things to reporters like, “Shoes have soles. Humans have spirits.” He has crashed awards ceremonies with acceptance speeches for TV shows he never worked on, worn a Kamala Harris-inspired wig on a livestream just after the vice-presidential debate, randomly pulled out accents to confuse reporters at press junkets.

I’m wondering how one reconciles a profound desire for attention with the concomitant need for privacy. Stanfield says he’s still working it out, how to be in the movies and the magazines while keeping what’s sacred to him sacred. It still baffles him the way people project certain moral and political responsibilities onto actors and musicians, how whatever they say is taken as gospel. It seems to me he’s been finding different ways to describe fame as unnatural or unhealthy, but he argues that celebrity isn’t necessarily a bad thing. When his publicists file into the motorhome, right on schedule, we’ve been caught in an exchange about fame and religion, Stanfield on a digression about the “cult of attention”.

“I think people tend to value who they think have value, and people who are popular seem to have that because everyone’s paying attention to them,” he says. “But placing all your faith in the human wouldn’t be the wise thing to do. Sometimes I think there’s too much importance placed on celebrity, and people think celebrities can’t make mistakes or can’t be wrong. Which is weird. Especially when anyone can be famous now, for doing anything at all.”

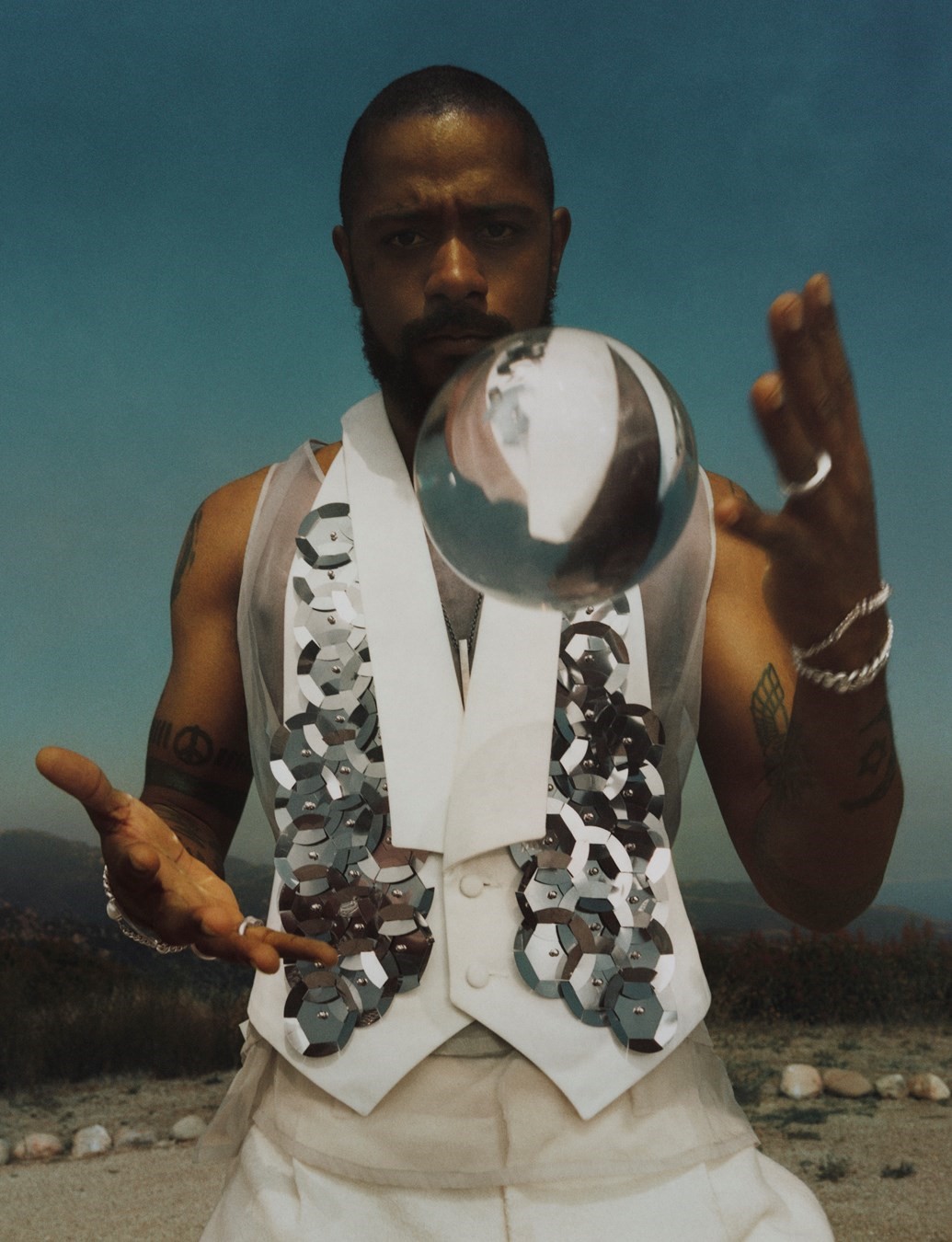

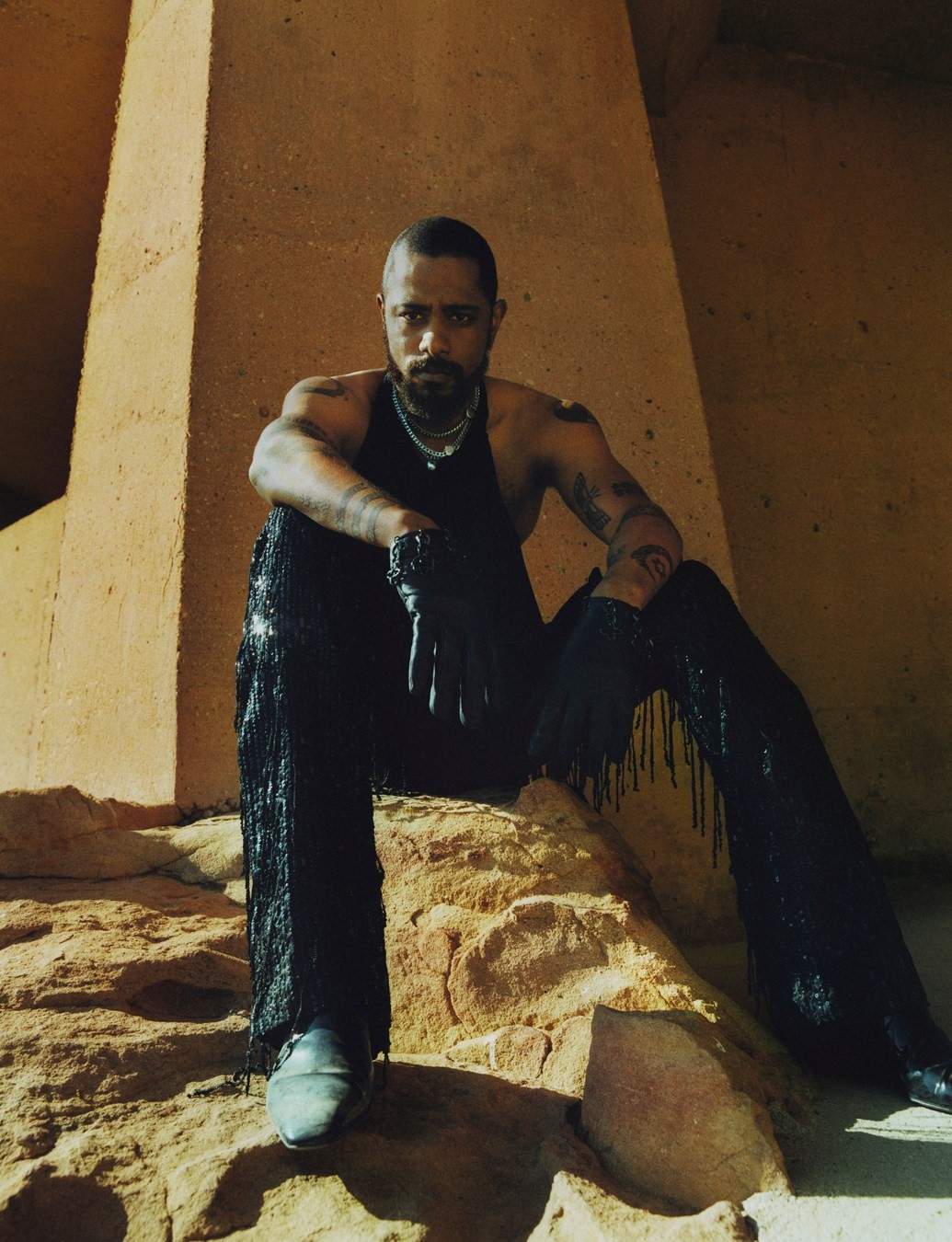

Grooming: Siân Richards using concealer and skincare by SIÂN RICHARDS LONDON and Bed Head by TIGI. Make-up: Frankie Boyd at Streeters using DANESSA MYRICKS BEAUTY. Set design: Patience Harding at New School. Photographic assistants: Bummy Koepenick, Todd Weaver and Cory Hackbarth. Styling assistants: Bella Kavanagh, Raphael Del Bono, Elliot Soriano and Gemma Valdes Joffroy. Make-up assistant: Megumi Asai. Set-design assistants: James Beyer, Mia Brito and Bradford Schroeder. Research: Daniel Obaweya. Printing: Sarah England. Production: Connect the Dots. Post-production: Ink

This story features in the Autumn/Winter 2023 issue of AnOther Magazine, which is on sale now. Order here.