In his Pulitzer-winning memoir Stay True, Hua Hsu knows the power of culture to define oneself. As the son of Taiwanese immigrants growing up in the 90s on the East Coast of the US, Hsu watches as his father tries to assimilate himself into American culture via his record collection, which includes albums by Bob Dylan, Neil Young and Jimi Hendrix. Eventually, though, he loses interest. “Becoming American would remain an incomplete project,” writes Hsu, “and my father’s record collection began to seem like relics of an unfollowed path.” Hsu, however, ploughs ahead; at age 13, he listens to Nirvana’s disaffected anthem Smells Like Teen Spirit – “my first glimpse into the prospect of ‘alternative’ culture” – and his world is forever altered. From then on, he wears exclusively thrifted clothes – floral button-downs, scratchy cardigans and corduroy trousers – and begins making music zines.

When he arrives at Berkeley years later and meets Ken, Hsu doesn’t like him at first. A “flagrantly handsome” frat boy who wears his baseball cap backwards, listens to Pearl Jam and Dave Matthews Band – “music I found appalling” – Ken makes Hsu uncomfortable not only because he is “generic”, but also because he is Asian American, like Hsu. “All the previous times I had met poised, content people like Ken, they were white,” he writes. What ensues, much to Hsu’s surprise, is a deep and formative friendship, nourished over cigarettes, car rides on the California coast, late-night philosophical conversations about music and film, and an awakening to the world of Asian American identity politics.

Then, less than three years after the day they first met, Ken is abruptly murdered in a carjacking – a catastrophic event that turns Hsu into a writer. “The day after Ken died, I stopped listening to songs from a specific zone of memory,” he writes. “Mostly, I became obsessed with the possibility of a sentence that could wend its way backward. I picked up a pen and tried to write myself back into the past.”

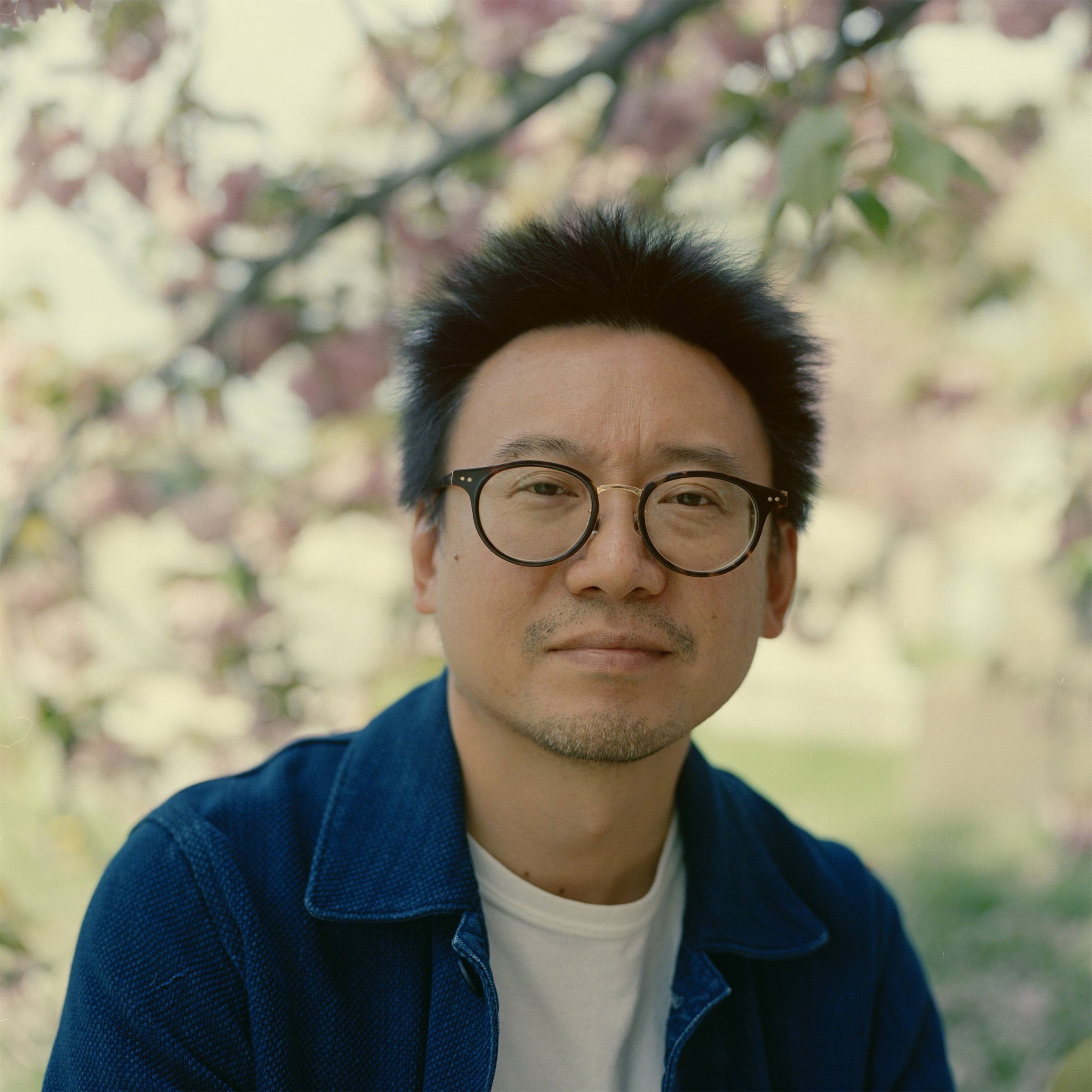

Over 20 years in the making, Stay True is an evocative coming-of-age story about the formation of identity, friendship, and grief. It is also a remarkable window into the birth of an esteemed cultural critic, someone who relishes the conversations that come with the consuming of music and film perhaps even more than the act of consuming itself. Today, Hsu is a staff writer at The New Yorker, and Ken’s influence can still be keenly felt in his work; much of his writing focuses on Asian American culture – he has recently covered the writer Ocean Vuong, the artist Nam June Paik, and the photographer Corky Lee. Of his early zines, to his criticism at The New Yorker, and now, in his memoir, Hsu says, ”I was always trying to process things through writing, it was very central to who I thought I was. I thought I could write myself into existence.”

Below, AnOther spoke with Hua Hsu about his memoir, Stay True.

Violet Conroy: How did you land on the title for the book, Stay True?

Hua Hsu: I think it was actually my agent’s idea. I’m bad at titling all things, so I hadn’t really thought about the title until we were about to submit it, and he said, “This phrase keeps coming up.” I’m pretty sure it was just in the air and it’s actually perfect because it’s hyperspecific. Like, it’s this inside joke that Ken and I had, but it’s also a vague idea.

VC: I noticed the word ‘true’ coming up a lot in the book – what relevance does it have to your life?

HH: When I was younger, the idea of truth – things being true, things staying true – meant that you had arrived at this final stage of completion. Being true to oneself meant that you had achieved yourself, or that you had become this finished product. But I think I understand it as more messy and contingent now. The idea of being true has more to do with principles and integrity, of sticking to that sense of who you might become, rather than assuming one day you’d be the finished article, which is what I very naively thought it would be like as a teenager. Like, you would one day grow up, and then you would just sort of be an adult. But that’s not necessarily how life feels.

VC: You write in the acknowledgments that you’ve been writing Stay True for 20 years. Did it begin life as a book?

HH: I certainly did not think it was a book. There are parts of the book that were written in 1998 but at the time it was just writing meant to get me through the day or to process things I couldn’t process. I turned to writing a journal in the immediate aftermath of Ken’s death because it was a way to feel as though I was present without being present. I wanted to return to this romantic time, and so writing felt very therapeutic in those first few weeks and months.

As I grew older, I understood that there was something about that period of my life and the effect that it had on my writing that I needed to return to. Around 2018, I started revisiting some of those journal entries and trying to figure out what the story was, partly just to figure out what my story was. Clearly, my relationship to writing was forged in that moment and I somehow did become a writer.

“I foolishly thought that the things I was into were so specific and so unique but obviously they’re not. Like, billions of people like Nirvana” – Hua Hsu

VC: So before Ken died, you didn’t keep a journal?

HH: I would write about my own sense of very generic teenage discontent with the time I was born into – how no ideas were original anymore and envy for previous generations – pretty generic stuff. [Laughs.]. So I was always trying to process things through writing. I made zines a lot as a teenager, it was very central to who I thought I was. I was just trying to figure myself out through writing – I thought I could write myself into existence. But yeah, my relationship to writing really changed after Ken’s death.

VC: Would you have written this memoir if Ken hadn’t passed away?

HH: Definitely not. I don’t even know that Ken and I would still be friends. You know, I think that’s sort of one of the unanswerable questions of the book. When your relationship to this question of friendship is so profoundly changed by loss, how can you be honest about the past? Suddenly, once there’s this interruption, all of a sudden there’s something that resembles a narrative arc. There are all sorts of questions I have to wonder about, like would that have happened had that not happened?

VC: You didn’t like Ken when you first met him. What did he represent to you at the time?

HH: He just seemed very generic to me. But I say this now, as someone who recognises how generic I was at the time too. I was a generic snob, and so I was ready to pull out anyone else’s generic qualities. He just had these qualities that were so different from how I felt inside or wanted to be perceived, but he also seemed so comfortable in his own skin, which is something that I didn’t know to envy. He just seemed very comfortable and generic, and those were qualities I had built my personality in opposition to.

VC: The book feels like a 90s period piece, with the technology, music and fashion. What was it like revisiting that period?

HH: I tried to put as little research into the book as possible and just operate off memory. What I was really trying to write about was the texture of that time. It’s not that the past was somehow better – which I think is a challenge whenever you write something about your teenage years – that wasn’t the intention. I just wanted to be able to reconstruct the textures and rhythms of what it was like to be 18 in 1995. Like, what it meant to be bored. What you could do if you were bored, what limited access to things would compel you to do. It was very liberating to return to that time, but it was important for me not to present it as somehow superior to the present.

“I made zines a lot as a teenager, it was very central to who I thought I was. I was just trying to figure myself out through writing – I thought I could write myself into existence” – Hua Hsu

VC: What did you learn about identity while writing the book?

HH: One thing that I came to appreciate is how clichéd so many of these questions I was asking were. When most people are in their late teens, they’re thinking through these questions of: who am I? How did I become this person? Who should I be friends with? Where’s my community? Where do I belong?

One of the jokes of the book is that I think I’m an iconoclast, but it’s actually an illusion. I’m just this generic product of the 1990s. I foolishly thought that the things I was into were so specific and so unique but obviously, they’re not. Like, billions of people like Nirvana. An entire generation of people were familiar with zines and going to music stores.

VC: Does it feel strange being interviewed by people about the book, when that’s been your job for so long as a staff writer at The New Yorker?

HH: Yeah, it’s very weird. I like interviewing people because it’s an excuse to have these conversations or ask questions. That’s one of the best parts of being a journalist, just being able to have these random encounters with people. It’s very strange to be on the other side of it, because I feel like the book makes it seem like I have a lot of answers to what it means to be a good friend or to be content or to be forward-facing. I don’t think I actually have those answers. For me, the book was an opportunity to figure some things out about myself for myself.

I think as a critic, or as a writer, you’re often ascribing intention where maybe there was none. In my book, I’m more open to the possibility that something was always there, I just didn’t name it until someone else came along and pointed it out. But I don’t know, maybe I’m just stealing the credit for smart readers.

Stay True by Hua Hsu is published by Picador and is out now.