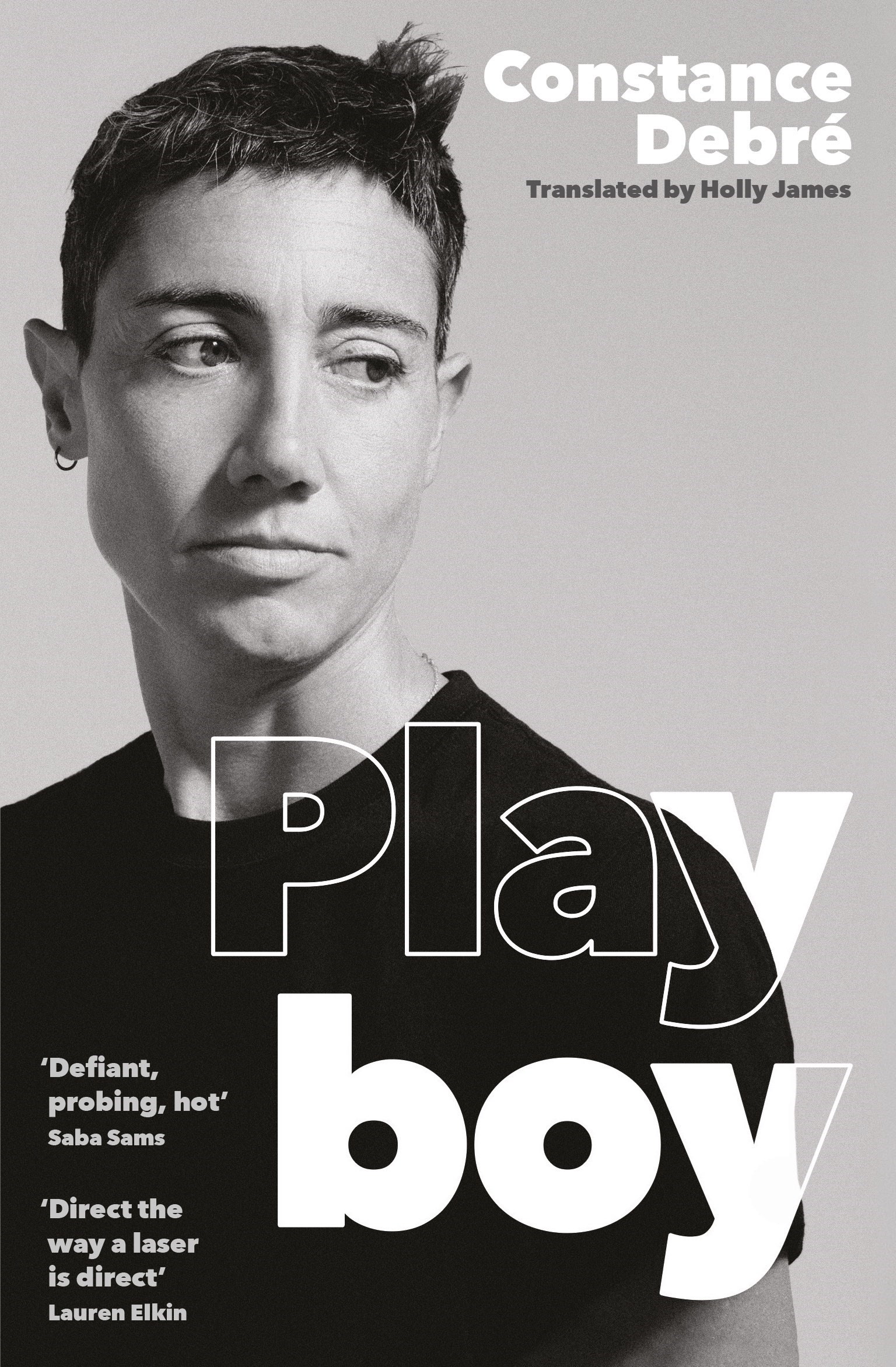

Playboy is the kind of book you can imbibe in one sitting. Its sentences are meticulously simple, doing the most with the minimum. They perfectly embody the voice of the novel’s unnamed protagonist; direct, almost to the point of flippant, but with a knack for cutting through the bullshit and confusion that emotions and relationships bring. Constance Debré, Playboy’s author, can say in one sentence what it might take others to say in hundreds.

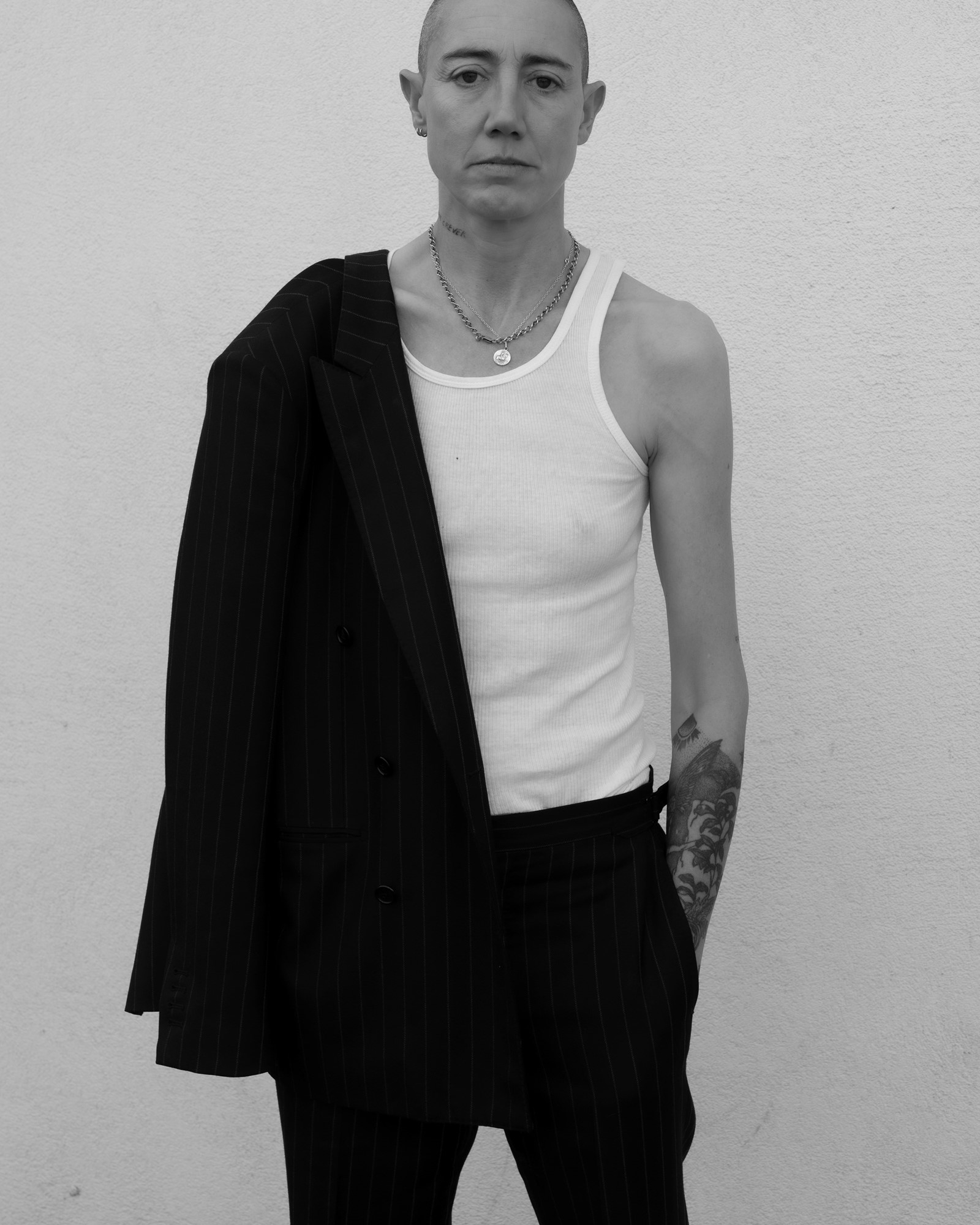

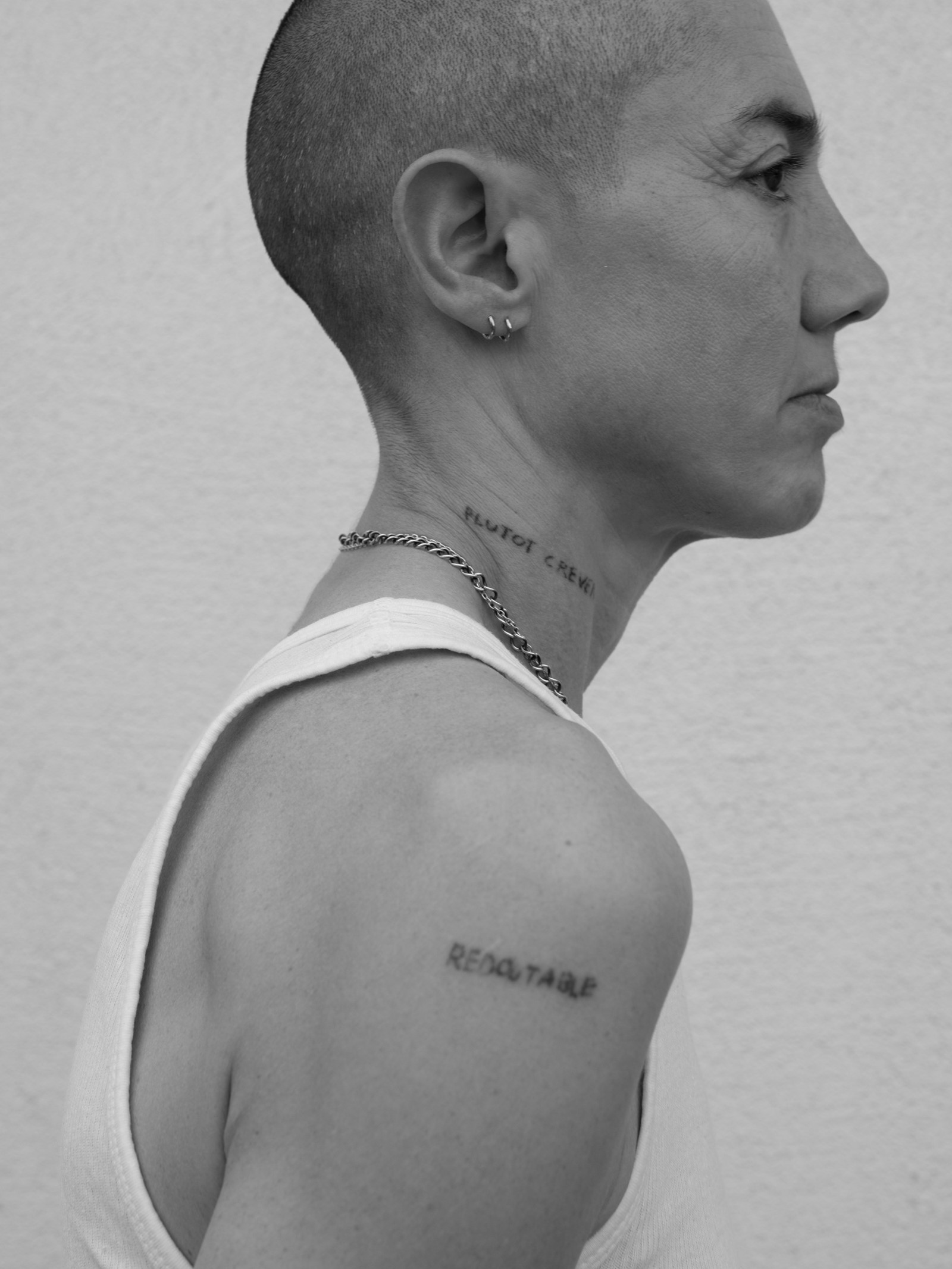

To what extent Playboy’s protagonist is based on Debré is up for debate, but both characters – like the text itself – are also “laid bare”, saying what others might be too afraid to. Both stripped their life back to reach something more “honest”, trading in the roles of lawyer, mother and daughter within an aristocratic French family, for that of writer, lesbian and self-proclaimed “lonesome cowboy”. Playboy follows this “coming out” journey, hanging out with our eponymous playboy in her near-empty bachelor-style apartment, at the local swimming pool, or with love interests in Paris cafes, as she recounts her new experiences with a compelling mix of arrogance and self-deprecation, distaste and humour, distance and desire. In a favourite line, she shares that doing the food shop was why she knew conventional motherhood wasn’t for her.

After Playboy was published in France in 2018, the book made Debré a divisive literary star, partly because Debré deservedly won several literary awards, partly because French readers were shocked to read a female writer recount having sex like a playboy, and partly because Debré comes from a well-respected society family. Two more books in the trilogy followed – Love Me Tender, about her custody battle for her son, and Nom, a meditation on the significance (or not) of lineage, among other things.

Now, Debré splits her time between Paris and LA, where she is closer to her American publisher Semiotext(e) and girlfriend. As Playboy is translated into English, we hopped on a Zoom call to discuss blowing up in “bourgeois” France, her literary influences, and subverting gendered expectations.

Amelia Abraham: You’re trained as a lawyer – did you always want to be a writer?

Constance Debré: Yes, I wanted to write forever, but that’s very common. I published two books in my early thirties. They were not good enough. I don’t even own those books, but I’m in LA right now staying at an old friend’s and she has them. So I looked at them and actually, they’re the same [as my more recent books] but also not the same; they are in the first person and talking about the body, but too vague. So I guess I was not ready then. I had to wait for another 15 years.

AA: What made you sit down and write Playboy when you did?

CD: There were many reasons. Part of it was related to being a lawyer; when you plead you try to grab people very efficiently and directly. It is almost a physical way to use language, standing, moving through the courtroom. So I wanted to use that, from a stylistic point of view. I also felt empowered by this experience of fighting for people. Then there is the coming out, it gives you this feeling of power. All those things came together and, at some point, it was time.

AA: You mention the precise and direct way you write, it’s simple but so effective – did it take time to cultivate the voice or did it come naturally?

CD: Both. You have something in mind, you have your natural style. Like the way you dress – it’s conscious but it’s also not. I thought, ‘I have this material, myself and recent events, but I am going to use it in a twisted way. It’s not like this is my true identity. It’s a lot of work. For me, at least for those first books, Playboy and Love Me Tender, editing is 90 per cent of the work. I can spend two days removing all the commas and then spend another week maybe putting some back in.

“Writing a book can be an arrogant position, thinking you have something to say ... It’s tiring how people are like, ‘Oh yes, I’m very modest’. I thought it was more funny, risky, sexy to propose another kind of hero” – Constance Debré

AA: You write very candidly about people in your life – your ex, the married woman you had an affair with, other girls you are sleeping with. Has this upset anyone?

CD: Not at all. No. The trouble was before writing, at least with the people who became characters in my books. [Laughs]. I haven’t talked to some of them, but they are aware that books are books, they are characters. It’s not about us. I mean, everyone in my life knows who is who, but even my enemies are civilised.

AA: What I find so captivating about the reading experience of your books is that you might say something brutally judgemental of another person and in the next line something equally brutal about yourself. You’re just as exposed as others.

CD: That is the least I can do. It’s not about the real person, they disappear very quickly and become a character, and that character has to have meaning for the people reading. When you say things about people you cannot be above them, or if you are, you have to be OK with the arrogance of it, too. Writing a book can be an arrogant position, thinking you have something to say. Sometimes I take it to the extreme, other times I am here to say we are all completely lost. We can go from arrogant to lost just like that. It’s tiring how people are like, ‘Oh yes, I’m very modest’. I thought it was more funny, risky, sexy to propose another kind of hero.

AA: When I read both Playboy and Love Me Tender I felt that I had been waiting for this hero – female, but with the traits that are more “masculine”.

CD: Of course. I wanted to write [these books] as another way to represent women, and to write in the first person as a woman and a lesbian. I am fed up with those too-nice women or victimised women. I wanted to represent a woman or a lesbian who is the opposite. To steal it – this idea of the playboy. It’s fun.

“I could have written long, sophisticated sentences, so the French reader thought ‘She’s smart’. But that’s exactly why I hate French literature nowadays ... Why do you think people are not reading anymore? Because books are boring” – Constance Debré

AA: Chelsea Girls by Eileen Myles is the only vaguely similar book I can think of, in that sense.

CD: Yeah, I read Chelsea Girls two years ago, so after I wrote Playboy. I love Eileen. But I have a very classical taste in books; Conrad, Proust and Balzac. It’s usually French guys. I’m not really in the queer culture. I don’t care about being gay, it’s my life, and I wanted it to be there in the first sentence, but at the same time, the books are not about that at all.

AA: I wonder if coming out later made you more like that? If you were younger, you would have felt differently.

CD: Probably, but it’s also my temper. Groucho Marx. I’ve always been a loner. But what I wanted to do – and I think it’s political – is to be very clear this is the point from where I am writing. But I want to write about the human condition, not this tiny position or place on earth. This is why literature written centuries ago can have such power. When I read Dostoevsky, I never think, ‘This was a man, heterosexual, Russian’. It’s about life. I think that’s what any woman or gay person has to do. It’s a standpoint to talk about the whole range of the human experience. I also didn’t need to quote all these other writers to do that. I could have. I’m an introvert more than anything, so I spend hours reading. I could have also written long sophisticated sentences, so the French reader thought ‘She’s smart’. But that’s exactly why I hate French literature nowadays. Get to the point! Why do you think people are not reading anymore? Because books are boring. Try to please the customer, at least!

AA: I know your books have been hugely popular in France, but have they also raised criticism or shocked people – specifically, I would guess, around the way you talk about women, like ‘the hairy one’ or ‘the skinny one’ in Love Me Tender.

CD: Yes. I mean, in France, it’s not even that. It's very bourgeois and middle-class in France, probably like 20 years behind London, New York and LA. They’re still not used to queerness in France, it’s still something new, or dangerous. Imagine a small town in the 50s. So when I came out – it’s like, ‘You’re so free, you’re a punk’. I’m like, I’m not a punk. I apologise to real punks.

About the critics, some people see me as something like a rebel. It’s this idea that all the violence comes from men, women are so nice. But we are human beings, that’s why women are great; we’re all mixed up, many things, we’re not better [than men]. Women can be cruel, violent and stupid. It’s kind of a joke, the name Playboy, but I was like, ‘Let’s go – let’s do it, let’s show how women talk with other people’. It has a kind of truth to it.

AA: Have you found a writer community through publishing books?

CD: Not in France, I don’t know why, maybe it’s me. But in LA yes, around my American publisher, Semiotext(e); Eileen [Myles], or Chris [Kraus]. Semiotext(e) is a special place; avant-garde, underground, fresh. I love LA, for the first time in my life, I found some kind of milieu where everything is easy. When we see those guys we don’t talk about book stuff, we just hang out. Two things people don’t talk about: my family name, and the lesbian thing, so then we can really talk about writing.

AA: What’s coming next, in terms of your writing?

CD: I have two other books published in France, Nom [Name] and Offences, that will be published in the UK and US next year.

AA: Nom is about your family name, right, which is less recognisable outside of France?

CD: Not about my name, exactly. We are living in a time when people are obsessed about what’s behind us or deep inside us; family, psychoanalysis, DNA, ancestors, etc. I think this is crazy. When we think about what’s going to happen (which is basically death) or when we think of the human experience (what do I do today) it’s not about talking about your fucking childhood. So I wanted to talk about that using personal stuff. Yeah, my parents were drug addicts and my mother died, but I’m not going to say life is about trauma. Can we think of ourselves as strong people who can go through that … and maybe find there is beauty in it?

AA: And Offences?

CD: It’s the most personal book, but it’s not in the first person. It’s a contemporary story about a young man in the suburbs of Paris who stabs an old lady. I could have said I’m the lawyer but I didn’t want to. Trials and murder are all over literature, and I wanted to write mine. It’s like my Crime and Punishment.

Playboy by Constance Debré is published by Serpent’s Tail, and is out now.