As a well-seasoned cultural critic, Lauren Elkin’s first foray into fiction reads exactly as you might expect. Her first book, Flâneuse, was a charming memoir and cultural history on the subject of the same name, while her second, No. 91/92: Notes on a Parisian Commute, chronicled life as a pregnant woman on a bus, calling upon the literary spirits of Georges Perec and Annie Ernaux. Her most recent book, Art Monsters, brought together an eclectic mix of thinkers and artists who challenge the way we think about the female body: Carolee Schneemann, Virginia Woolf, Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Jenny Offill, and Simone Weil to name a few. Although Scaffolding is in many ways the perfect lovechild of both these projects, Elkin forgoes the restraints of non-fiction here to conjure up something entirely unfamiliar instead.

The story is this: in modern-day Paris, psychoanalyst Anna befriends her beguiling neighbour, Clémentine while processing a miscarriage. As Anna’s world begins to collapse around her, she questions everything she thought she knew – the limits of desire, the meaning of art, and what it means to become a mother. 50 years beforehand, psychology student Florence longs for a baby but her husband Henry isn’t so sure.

A few things tie their stories together; the same apartment, a love of Lacan, a yearning for more. As Clémentine beckons Anna to join Les Colleuses, the radical feminist collective exposing France’s femicide epidemic, Florence’s tale takes place against the backdrop of France’s sexual revolution. At its core, Scaffolding is a story of womanhood, but the magic of Elkin’s prose is its disregard for structure altogether.

Ahead of Scaffolding’s release, AnOther spoke with Lauren Elkin about psychogeography, motherhood, and feminist historiography.

Katie Tobin: You’ve mentioned that the book took you 16 years to write. How did it change over time?

Lauren Elkin: It was a really long process of refining, of getting closer to the characters, to their voices, to their range of possibilities. That was also a part of getting to know myself as a writer, my own range of possibilities. Part of why I couldn’t finish it more quickly was because I couldn’t imagine what could possibly become of these people in the situations I’d found them in, because I hadn’t lived long enough or seen enough of the world.

KT: Having read Scaffolding so close to Art Monsters, it struck me how grounded the texts were by the same theoretical mood and thinkers (Chris Kraus, for one). What was it like integrating these ideas into your first work of fiction?

LE: It took me a while to understand how to integrate theoretical moods, as you so excellently put it, into my fiction. As a fiction writer, I had always felt very uncomfortable with story, with plot, and it was a great relief when other fiction writers have found a way to be in the world of the text without it having to be about ‘then this happened’. I’m thinking of writers like Sheila Heti, Teju Cole, and Chris Kraus – writers of situation. And so reading them helped me see how I might explore a given world, and an ambience, without having to worry about what would happen.

Chris is someone whose work I’ve been living with for a while now, since I interviewed her for The White Review (RIP!) in 2013 and did a deep dive into her work – I Love Dick was my gateway to Chris Kraus but there are so many other riches there, it’s no surprise to me that the major projects I’ve undertaken since then are so explicitly engaged with her work. That she has been so supportive of my own work, by publishing it and blurbing it, remains one of the central reasons I feel able to keep making it.

“My own experience of motherhood is compacted into the final pages of the book – the way it constrains you, and redefines your relationship to yourself, your home, and your partner” – Lauren Elkin

KT: I’ve noticed that you’ve returned to the 1970s in your writing on a few occasions as a point of historical and cultural significance. What is it about that period that keeps drawing you back?

LE: It’s no coincidence that it’s the decade when I was born – aren’t we all just fascinated by the worlds we were born into? When we were teenagers in the 90s, 70s fashion was all the rage, bell-bottoms and loud shirts with crazy big collars and what they called “poorboy” ribbed jumpers. Now the kids who were born in the 90s are dressing like it’s the 90s, and Gen Z, who were born in the early 00s, are dressing like Paris Hilton.

But seriously! I originally set the middle section of Scaffolding in 1972 because I was interested in the legacies of May 1968 – what changed, what didn’t change, how were they absorbed into French life, how could their impact be felt on my own day, why was it all led by men, where were the women? And over the period of time that I worked on the book, I worked on my PhD thesis, which was about British women’s writing in the 30s and the state of the feminist project at that time, after they (mostly) obtained the vote in 1928. I got really interested in feminist historiography, in feminist movements and how they start and what becomes of them, and how we go on talking about them, or not, and that fed right into Art Monsters. So by the time I was finishing the novel, I had a lot more imaginative access to feminist activism, and including the Colleuses in the present-day, the consciousness-raising group that Florence attends in the 1972-73 section, the Bobigny trial, the 343 salopes.

KT: There’s a passage near the end where Anna’s voice becomes blurred with the sounds and sights of Paris. You can really see how the literary genealogy of your other work – especially Flâneuse – shapes this moment. How did you get in the zone for writing this section?

LE: I was in Paris when I started it, in Belleville having a drink in the bar that Anna and Clémentine go to (Combat) before meeting a friend for dinner, and some combination of the wine and the setting and the way Belleville had changed since I’d lived there just opened a tiny door in my mind and it all came flooding out. Once I was back in London I pulled it together looking at Google Maps, looking at pictures, reading my Paris diaries. I felt somewhat self-conscious writing it, thinking oh dear, this is going to read like Flâneuse: the novel, but I couldn’t help myself – it suddenly seemed very obvious to me that the dénouement of this book about a woman cling-filmed to her couch was going to involve a good long traipse through the city.

“How to live with the self, with a body that fails us, or amazes us, that tries to dictate how we live our lives, how we respond to its activation, its desires?” – Lauren Elkin

KT: I felt like the thesis of the book – if you can call it that – were the characters trying to figure out forms of relationality to others, to time, to the world around them and to themselves. Do you think Anna ever succeeds in doing that?

LE: I think she does in a kind of durational way; she’s struggling at the outset with how to live with other people – her partner especially, her family a bit – and also with how to live with the self, with a body that fails us, or amazes us, that tries to dictate how we live our lives, how we respond to its activation, its desires. I think by the end of the novel she’s settled in a bit more, has been able to accept certain things that she knew intellectually but couldn’t quite integrate into her own life.

KT: For Anna, Clémentine and Florence, motherhood means something wildly different to each of them. What was it like writing their stories while becoming a mother yourself?

LE: It’s funny because I went through so many different attitudes towards motherhood over the course of writing the book; I used to be someone who didn’t want kids, I would have sworn to you, had you met me then, that I wouldn’t become a mother, and then I sort of felt like I wanted them but not yet, and then when I met the right person it was a given that I would have one. So I can understand each character’s perspective because I’ve been each of them. And then my own experience of motherhood is compacted into the final pages of the book – the way it constrains you, and redefines your relationship to yourself, your home, and your partner. But I still remember what it was like not to want them – that still seems to be an eminently valid and important way of being in the world.

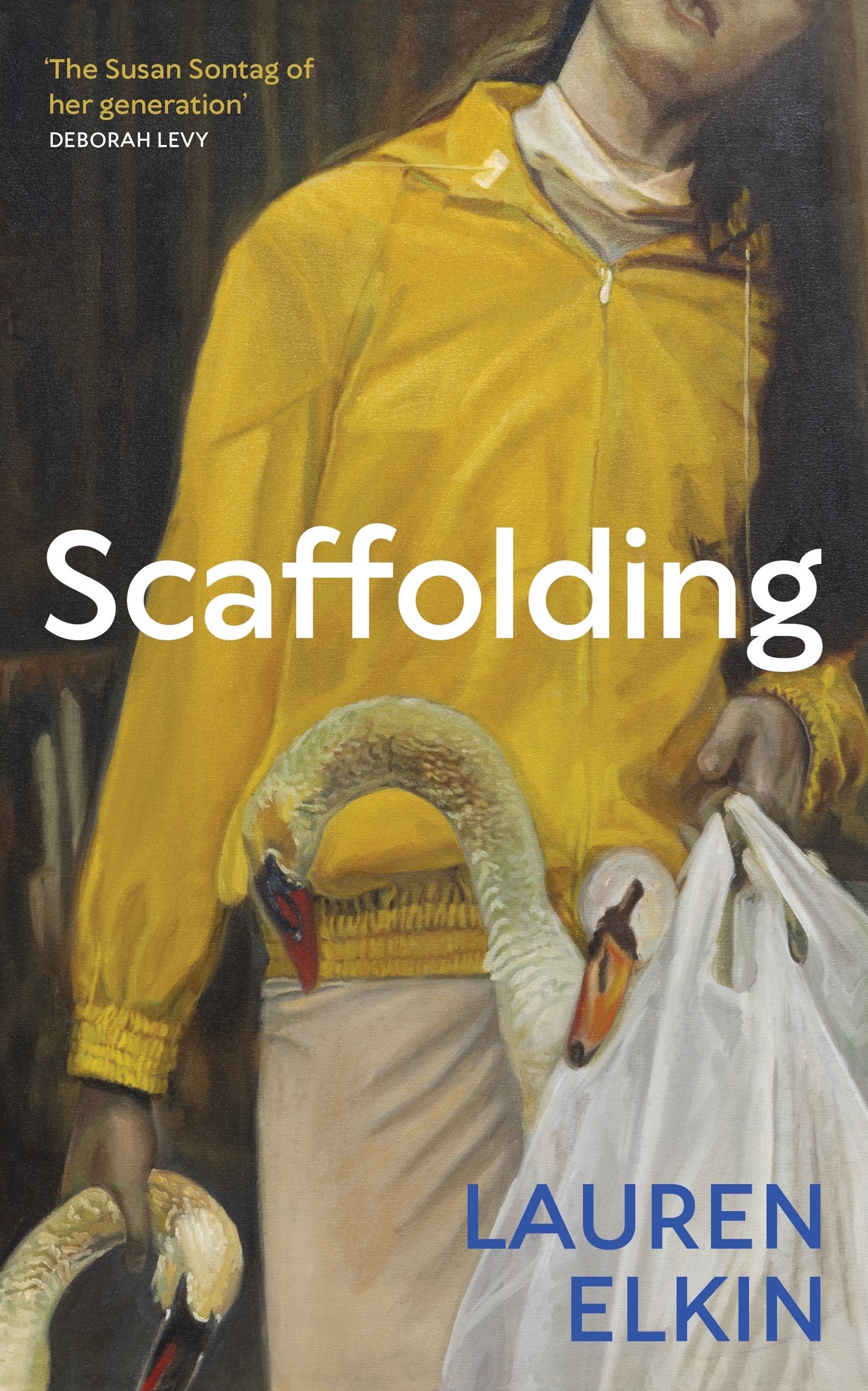

Scaffolding by Lauren Elkin is published by Chatto & Windus, and is out now.