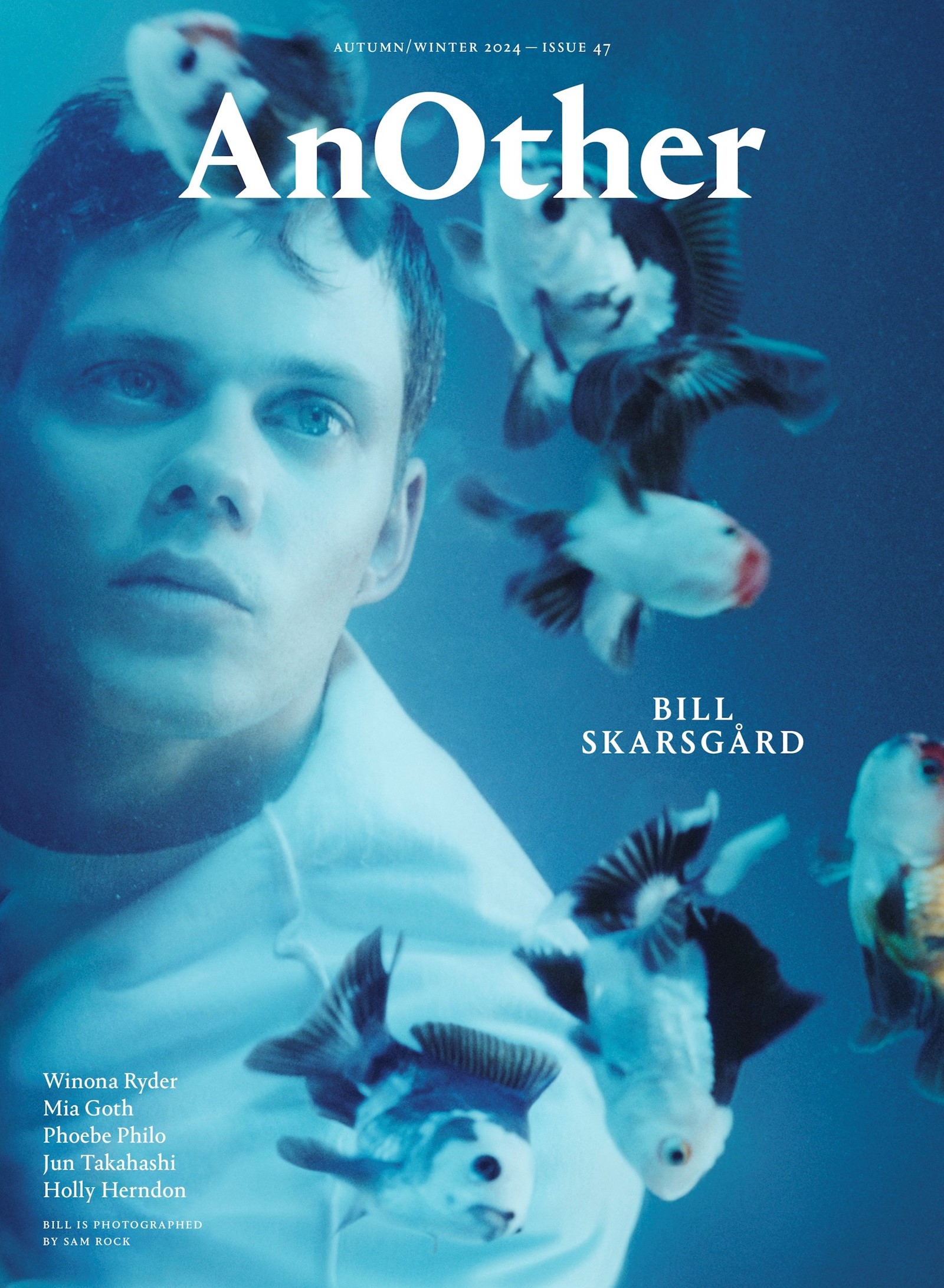

This article is taken from the Autumn/Winter 2024 issue of AnOther Magazine:

Having arrived at his countryside house in the Swedish archipelago for his mother’s birthday, and armed with a cake for the occasion, the actor Bill Skarsgård speaks to the director Robert Eggers about the soon-to-be-released Nosferatu, the horrors of moviemaking, the role of monsters in societies past and present and what it takes to embody the most famous vampire in history.

Robert Eggers: Well, hey dude.

Bill Skarsgård: Hey, man.

RE: It hasn’t been too long, which is nice. But I’m going right in. What were your initial reactions to the original Nosferatu films – the FW Murnau version from 1922 and Werner Herzog’s from the 70s?

BS: Well, the Murnau film I saw for the first time when I was very young. My dad showed it to me – I was probably too young to understand what it was, but it was unlike other silent films. The runtime was accessible for a child and I knew that it was a significant film. It shook me. Ironically, in a short silent film I did in Sweden when I was 16 or 17, my character’s name was Teenage Nosferatu, shot with …

RE: He’s doing a hand-cranked motion, AnOther Magazine.

BS: A hand-cranked camera, yeah – it was about a maid who worked for a posh family. And I was playing the teenage son. So I studied the original at 16. I had bleached hair – I was a punk Nosferatu at 16.

RE: I’ve never heard this before.

BS: It’s all coming out now. The Herzog one I watched in my early twenties when I did a Herzog deep dive, and it’s a different beast altogether.

RE: We had similar beats, then. I saw Murnau’s film when I was nine, and the cool thing was that the VHS I had was from this degraded 16-millimetre print, and you couldn’t see the line of the bald cap or the grease paint and Max Schreck seems like a real vampire — that is what hooked me on his performance.

I love looking at the newly restored versions where you can see Murnau’s intention, but I don’t know if the film would have haunted me in the same way had I seen those as a kid. I directed a play of Nosferatu when I was 17, so I had a big romance with it around the same time, too. And I watched the Herzog one a lot as a teenager, although my general Herzog deep dive was also in my early twenties. Klaus Kinski and Isabelle Adjani gave these miraculous performances. I’m glad that we didn’t have to front light everything with our pace of shooting, though …

So how did we do this together? How did it all come about on your side? It’s a weird story.

BS: It is. And obviously it was all in your hands. But the first time we met I had just watched your film The Witch an hour before. I was in a hotel room in New York and I had such a euphoric experience watching it – I was so incredibly impressed. Films resonate differently on any given day or period of your life and that movie just spoke to my soul at that time.

Meeting you, I felt the same way. We’re similar in age, you’re a few years older but I thought, here’s the first true auteur of my generation. And I felt such an instant connection with you and huge admiration. Those meetings are like blind dates.

RE: Yeah, they can be pretty …

BS: They can be terrible, they can be wonderful. But on this one I thought, I’m destined to work with this man in some capacity and I’ll do whatever it takes. At that point you were doing The Knight and then that fell apart.

Nosferatu was supposed to be your second film. It’s a story you’ve been destined to tell for a long time. Reading that script, it was the same feeling I had when watching The Witch. Like, whatever is going on in this madman’s brain is resonating so profoundly with me. And this was seven, eight years ago. I was 25 probably. I originally read for the [Friedrich] Harding role, I self-taped for it. I wasn’t very pleased with my self-tape, as always.

RE: You taped for [Thomas] Hutter too. I remember that audition being excellent.

BS: I was in LA and I needed to be very skinny for the show I was doing at the time, Castle Rock. I was gaunt, which was great for Hutter. And when I was originally cast as Hutter, I’d never been more excited about a collaboration or a role in my entire life. It felt like it was meant to be, it was going to be the most amazing experience ever. And then of course it fell through.

RE: But – I’m sure you feel the same way – I believe in getting the cast that was meant to be, I do.

BS: Yeah, for sure. And then you and I were supposed to work together on The Northman, which I was also very excited about, even though that was your baby with Alex [Skarsgård, Bill’s brother]. And then Covid happened. The movie got pushed eight months and I ended up in a massive scheduling conflict and that fell through too. I was like, I’ve tasted Eggers, I’ve tasted what a collaboration with him would be like.

RE: You were in Belfast dressed as a Viking, doing the camera tests the day before we shut down. You had the hair, the beard and the arm rings – everything.

BS: They couldn’t get all the hair extensions out in time for my flight. So I was sitting on the plane back to Stockholm pulling out hairpieces. That was a weird time for everybody.

So, after The Northman, we hadn’t spoken, and my agents and [the producer] James Farrell said, “All right, it sounds like Eggers is going to do Nosferatu next.” And I said, “OK, well, do I still have the Hutter role, what’s going on?” “Well, he’s looking at other things, other people.” So I wrote this very earnest, embarrassing email to you saying, “Please, please, please, I’ll do whatever — I need to work with you.”

I heard you ended up casting Nick Hoult as Hutter. At that point I was like, I’m done, it’s over. I’ll have to forget about Rob, forget about this potential collaboration. Just move on. Best of luck to him.

When you reached out about the Count Orlok role, I was in complete shock. And utterly terrified … but also excited. It didn’t make any sense to me at all. But we spoke on the phone a lot and you shared your thoughts about the character, the look of the character. You shared files of your own concept art and a backstory. So I put myself on tape for it. It was so abstract – we had ten days where I would just record things and send you voice memos and little things I was exploring. And you would gently steer me off certain things, towards different things.

It had stopped feeling like an audition, it was a full-on dating phase and I had no idea if I could give you what you wanted. And we had that read over Zoom with you directing me. I had long nails I’d picked out from a costume department in Stockholm.

It was this beautiful exploration of the character that was so generous of you. But this is how I would want to audition for anything, to explore what a director and an actor can do together. It’s very different from the run-of-the-mill self-tapes or casting calls … And then you wanted me.

RE: Well, I clearly wanted you to get the role or I wouldn’t have gone through all that hullabaloo. Because I had the realisation that, for Orlok to be a corpse, and for the romance to still work, it would be helpful for the audience to know that there is someone young and beautiful under there. And I thought, Bill’s so tall and so skinny, which is perfect for the physicality I was looking for, and he’s so good … And then I saw It Chapter Two. The scene where you’re Pennywise but as a guy …

BS: Yeah, Bob Gray, the human.

RE: That was terrifying and truly dark. I totally believed you as this older, dark person. That’s when I thought, Bill can do this. But we needed to be totally sure, so we needed to do the audition. You were incredible, it was undeniable. And it was fun. It was fun to do all that work, which also psyched me up for the continuing collaboration.

So did you ever ask Alex about what it was like to work with me?

BS: Yeah, we talked about it and about his general experience on The Northman. He was so positive and said how much he loved you and Jarin [Blaschke, the cinematographer]. It sounded like a gruelling shoot for him but one of the true high points of his career – he felt the obstacles and hurdles were more than worth it in the end. But because I’d met you years before, I felt like I had my own thing with you. The weird part for me was that we did that read a year and a half before we ended up shooting.

RE: Well, yes, because the movie fell apart. Again.

BS: By the time the movie finally came up, I was in pieces. I was not in the same place any more. I was listening back to my voice memos from when I was in this hole – things were happening in my life at the time. I was trying to emulate what I did a year and a half ago, but I was so detached from it that I thought I couldn’t be as good as I was – even for a read.

I really appreciated our month before shooting in Prague, where we would rehearse and talk about it all. Essentially I locked myself into this haunted hotel room and was kind of going insane, which I needed. I would walk along this corridor, trying to get my voice as deep as I possibly could. I think I have 500 voice recordings.

RE: I remember you worked with Ása [Júníusdóttir] on lowering your voice and Marie-Gabrielle [Rotie], the movement choreographer who is instrumental in Lily [-Rose Depp]’s performance and your death scene together. But in the beginning I thought she was going to have a lot more to do with your physicality. And there was a point where both of us felt you were doing too much stuff. Once you were in all the make-up, the costume, you just needed to be. You had the full make-up on for one of the first times and you were like, “Yeah, I don’t really need to do much. I just went to pee in the make-up, saw myself in the mirror and it was the scariest experience of my life.”

BS: The closest I have in terms of this experience is obviously Pennywise and the Bob Gray thing, where you’re creating something so make-up dependent, but also so abstract from who you are – it’s an abstraction. But with Orlok I couldn’t use any of myself in it. Like, Bill cannot be here at all. And that’s terrifying. I had a hard time committing to performing it, it felt so strange and uncomfortable.

RE: I also remember we were doing a read-through and Ralph Ineson was there, who has the lowest voice ever. And you were like, “I can’t do the voice in front of Ralph.”

BS: I was sitting next to him during the read-through. Right next to him – and his voice was low even for him. He’d had a few beers the night before. And I could feel my tiny chest reverberating with every word he said. And I’m like, why isn’t he playing Orlok? I go through all this pain and misery and I’m not even close to how low he is.

RE: I asked Ralph if he could try to speak in his higher register in the movie.

BS: Yeah. What, he laughed it off? [Laughs.]

RE: But what was the process for you of how the make-up evolved? It didn’t evolve that much – it was delivered to you, maybe to your shock and horror. But if there was an evolution in the costume, how was that for you?

BS: David White did such an incredible job on the make-up, but also it’s designed by you. It must be such a pleasure for someone like David to work with a director that is so specific.

RE: Working with these incredible people boosts your ideas. So, yes, I had the face and the shape of the skull in mind, and David honed them. But David had the cool idea – I won’t give away how – but he’d found a way to acknowledge the shape of Max Schreck’s ears. I wanted him to be a dead person, not a creature.

BS: It was amazing. When I saw the first moulds, where they had used my face cast and built on top of it, I was like, “OK, well, this looks absolutely nothing like me.” Not only is he a dead corpse, he also never looked anything like me when he was alive. I was terrified — I didn’t know if I could bring life into this, if I could carry this face on top of mine, if I could make it feel real. Once we had the first make-up test and they put all the pieces on, but before they painted it in and put on the wigs – the last touches – I looked like a goblin. I was looking at myself in the mirror like, this is terrible, this is terrible.

RE: I remember. I remember the displeasure.

BS: But once we put all the pieces together and played around with the tone of the skin, getting it darker and blending it more, then I could see my eyes brought life to it and my face moved in a way where it felt very real. That was the first indication that maybe I could do an OK job with this.

RE: I remember that moment too – you getting inspired. I was relieved.

BS: It worked. It’s an incredible design. But it wasn’t until a camera test where Jarin had lit all the candles and I was sitting with the full make-up and costume on that I felt all my preparation melting away. Once the camera rolls, and even more so when it’s on film and it’s locked and loaded, this thing just started to live and breathe in front of the camera. I was like, yeah, there he is.

RE: I distinctly remember that it was the second on-camera make-up test in full costume. I said to everyone nearby, “He’s Orlok now. He’s found it. It’s there.”

The set was serious, aside from maybe a couple of times with Nick, where, because of the explicit nature of what you guys were doing, it needed a little bit of horsing around. But within the seriousness of the set atmosphere, you were able to be chill and then be Orlok, which was awesome.

BS: But I have to say, I’ve never been more terrified of a role and probably won’t be again. The whole journey was so intense. Once you start channelling something that’s not you, you feel like a vessel. And you can go entire movies where that doesn’t happen at all or it happens in moments, but that’s always what you’re striving towards. In that moment, the doors are open and it’s flowing through me. I’ve never prepared this hard for anything before either. But once we started shooting, Orlok was very formed and he started to flow. I could connect and dial up to wherever Orlok was and he would come through. It was an intense ride.

RE: Well, I’m so grateful for everything you put into it, which was all of yourself and finally none of yourself.

“I’ve never been more terrified of a role and probably won’t be again. The whole journey was so intense. Once you start channelling something that’s not you, you feel like a vessel” – Bill Skarsgård

BS: Yeah, exactly.

RE: But it’s really an astonishing, complete transformation. What was it like with the other actors? How was it being this beast with Nick versus Lily? I mean, Lily was truly frightened of the make-up. Obviously she’s an adult woman in the entertainment industry and knows it well, but she was truly scared of the make-up. What was that like?

BS: I basically only interact with Lily and Nick. Well, there’s that one scene with Simon McBurney as well. But Nick is my rival, in a weird way. Everything I did with Nick – or with Hutter – was fuelled by hate and loathing, disgust that he’d dare rival me. There were so many of those types of emotions in our scenes. A bit like playing with your food, but more sinister. And the scenes were so intense and sometimes almost comical.

RE: Yeah, certainly on set, they were comical. You were so grounded in Orlok by that second test. I remember I texted Nick after his first week of shooting and said, “I need to call you.” And I was like, “I’m sorry, but your sideburns aren’t working. We have to give you new sideburns.” He said, “Oh my God, I thought you were firing me.” That attitude was helpful in the first couple of weeks of shooting, when he needed to be terrified in the castle.

BS: It was like Orlok was tormenting Hutter and Robert was tormenting Nick in those scenes. Because he’s the eyes of the audience, but he’s being mentally, physically and spiritually tormented by this thing. And then Nick is such a sweet guy, so between those takes, he’d say, “Hey Bill, do you want some water? Are you too hot?” And I was like [in a gruff voice], “No, no, no. Leave me alone.” [Laughs.]

And then with Lily, it’s the complete opposite. She’s the source of Orlok’s twisted obsession. And of course it’s not love, but an addiction of sorts. I was blown away by her performance when we were shooting – even when I was just a shadow of a hand, which is when, as an actor, you get to appreciate it the most because you’re not really in the scene, so I could just watch her work. Whereas when we were doing our moments I’d get so caught up in what it meant. But the way she committed to this movie … when I watched it, the jaw-dropping scene is the one between her and Hutter, where she’s possessed. It was the most terrifying, unsettling thing I’ve ever seen and it’s all happening in front of the camera. There’s nothing else – it’s just her and a beautiful shot. It’s out of this world, quite literally.

I was in awe of what she was doing. God knows it wasn’t easy for her. This also ties into what Alex had said to me previously, which is that with all the technical aspects of where the camera moves and how a scene should be blocked out, you’re tiptoeing and dancing with the camera, and at the same time trying to be real and die in agony slash ecstasy. It was hard. But I think collectively we’re so thankful to be a part of your film – that makes the whole torturous journey worth it.

I don’t know if I told you this, but we were doing the final scene, which in terms of technicality was the hardest one for the camera and for us …

RE: I don’t know if it was the hardest one for the camera, but the way you had to contort yourself for the camera to get over you, and the timing with the lighting and the degree of the emotionality of it, plus there was blood and bullshit – yeah, it was hard.

BS: It was hard and it’s the climax. You also told me during rehearsal, “This is the only thing in the movie where I’m not exactly sure what it’s going to be.”

RE: Well, it’s weird, but the way they died in the play I did as a kid was very similar to what we ended up doing in the film. But I thought that what I had done in the play was wrong, and so I was trying to do something else. And then when we kept rehearsing with Marie-Gabrielle, and I realised that my instincts when I was 17 were actually spot on, it was much more about Orlok and Ellen’s relationship – whatever that may be. But it took a long time to get back to that innocent idea.

BS: Yeah, so I think we were on take 14 …

RE: It might have been 31 takes in the end.

BS: OK. If we did 31, this was maybe around the 19 mark then, and I’m getting so exhausted and frustrated. It was, “OK, that light was off,” or, “You blocked her,” – all these things you must be conscious of at the same time as doing this very emotional moment. So the sweat starts building underneath the body make-up and I have pools pouring out. Lily’s tired and I’m getting tired. And Lily’s like, “All right, how was that one?” And you said, “I think it was good enough to be in the movie.” And she’s like, “Well, that doesn’t sound very good.” And you said, “What do you mean? I said it was good enough.” And I thought, oh shit, yeah, that’s what we’re striving for. And something shifted in me, like, we need to be good enough to be in this movie. I had so much respect for you in that moment. I was like, all right, we need to be good enough to be in this masterpiece. That’s what we’re doing. And so, 15 more takes.

RE: We used the second-to-last take, if that is any consolation …

BS: [Laughs] Oh, yeah? OK.

RE: OK, there is a question from AnOther Magazine on my piece of paper about why we’re still so fascinated by vampires, which I’ll let you answer if you wish. But what I prefer to think about is that, in the time when people were thinking their relatives really were vampires, when there was an epidemic of digging up bodies and cutting out their hearts and cutting off their heads and trying to remedy the village of vampires, vampires were a truly scary and real thing.

“The idea with this film was to come back around to a scary vampire again – a monster” – Robert Eggers

Dracula in the novel is a sadistic bastard. And then somehow, as the 20th century progressed, they became sad vampires. In 1979, Kinski’s sad vampire was the right vampire for that time. That climaxed with our friend Rob [Pattinson]’s Edward Cullen, who’s not scary at all, just a romantic hero. So the idea with this film was to come back around to a scary vampire again – a monster.

But as much as that was my intention, you also wanted to know when Orlok was vulnerable. Which was almost never, but I’m glad you found some moments of that.

BS: I think part of the reason I wanted to work with you so badly was that you bring back these dead, folkloric times and you blow so much life into them – they transport you into that period. Of course, we’ve lost a lot of that magic in our secular, science-driven world. Going back to these ancient tales is a reminder that they’re all in us — the archetypes are all there.

We have a need to go back and explore deeper. In this movie, what clicked for me was that it’s Ellen’s story. She’s stuck between benevolent love and a very destructive force. I represent the destructive force and she’s repelled but at the same time attracted to it. That felt very human. You could swap Orlok for addiction or abusive relationships. He’s this force you’re drawn towards. You don’t know why, but you are – and you know it’s certain destruction.

RE: Nicely said.

BS: Also, vampires should be terrifying. I don’t think we’ve seen them terrifying for decades now. And trying to bring life to this original, authentic idea of what it was or what it represented to real people who lived and believed these things is commendable and cool.

Nosferatu is in cinemas in the US from 25 December 2024 and in the UK from 1 January 2025

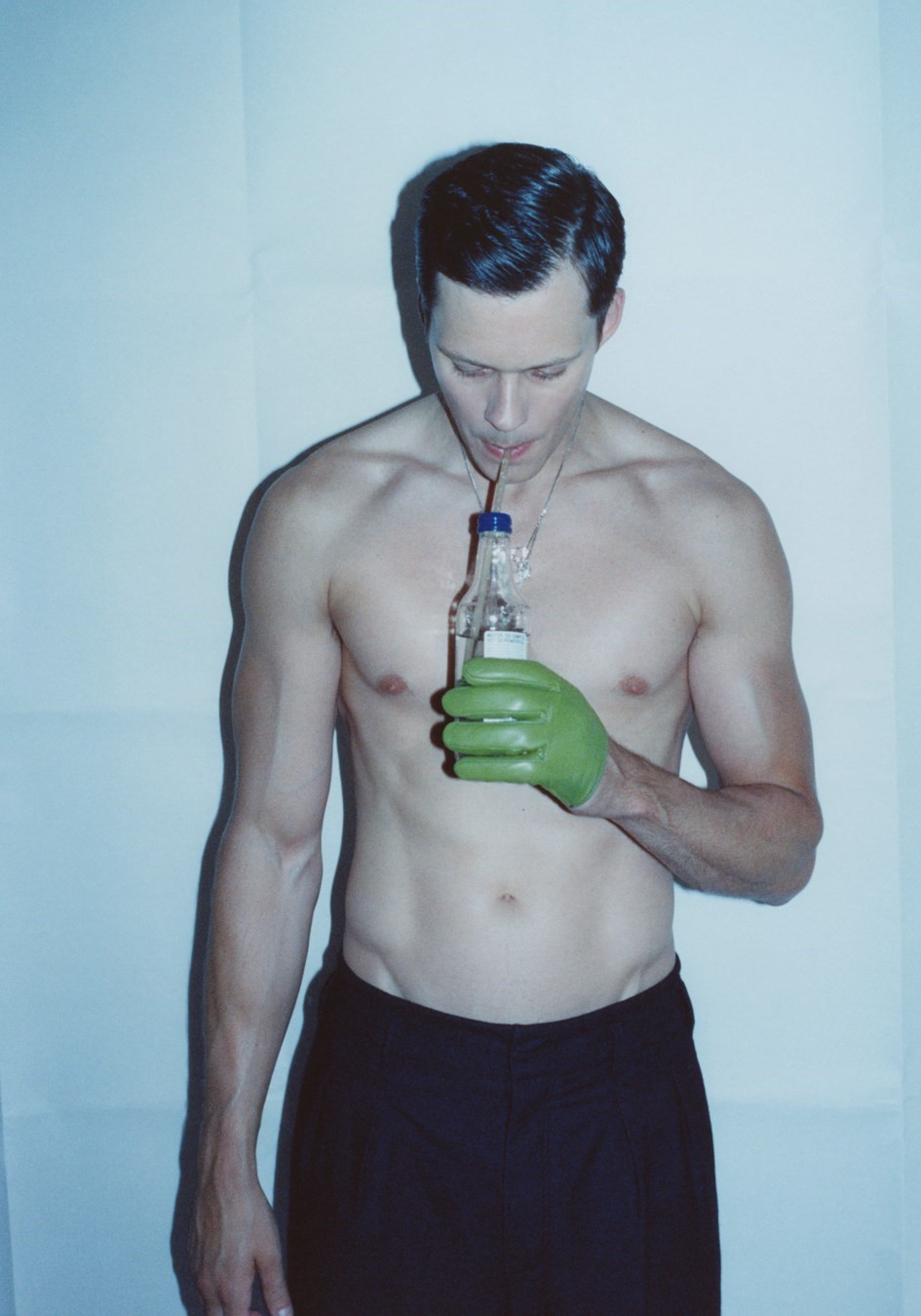

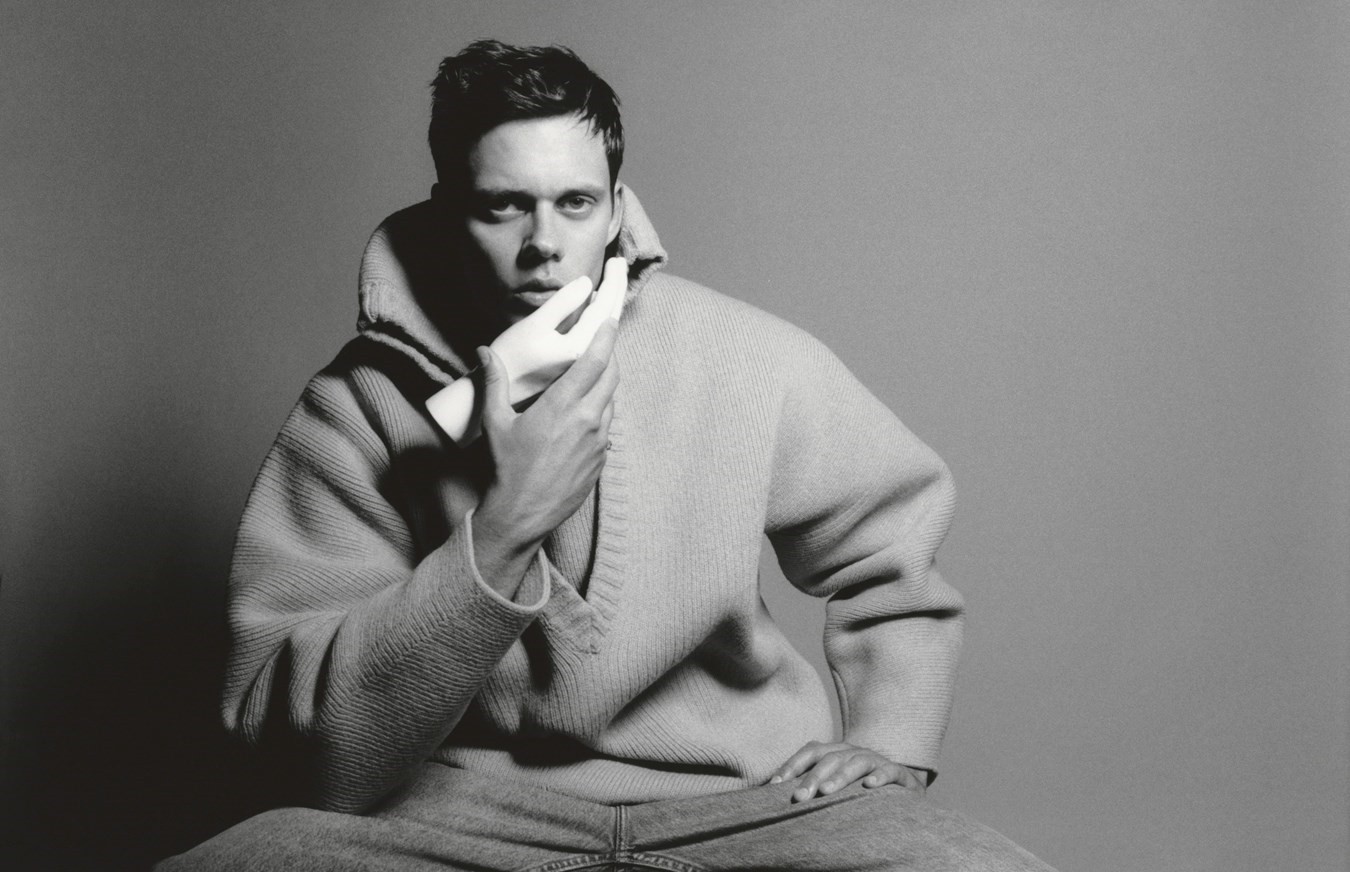

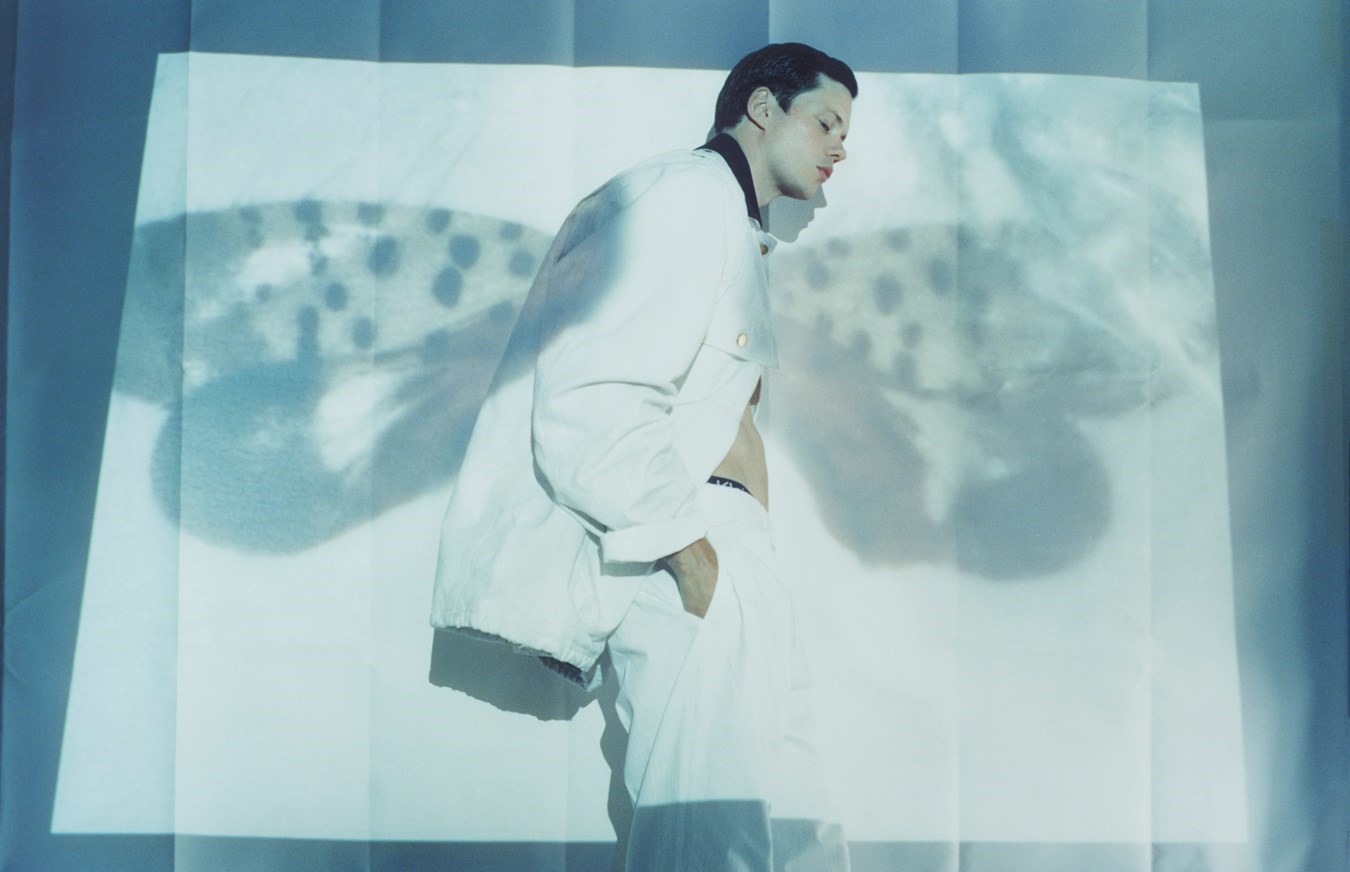

Hair: Claire Grech at Streeters using ORIBE. Make-up: Mel Arter at Julian Watson Agency using ULTRA VIOLETTE. Set design: Afra Zamara at Second Name. Photographic assistants: Joe Reddy and Jack Symes. Styling assistants: Izzi Lewin, Inês Bizarro and Belinda Nelson. Tailor: Nafisa Tosh. Make-up assistant: Mari Kuno. Set-design assistants: Evie Nairne and Charlie Heath-Martin. Retouching: The Hand of God. Production: Holmes Production.

This story features in the Autumn/Winter 2024 issue of AnOther Magazine, which is on sale internationally on 12 September 2024. Pre-order here.