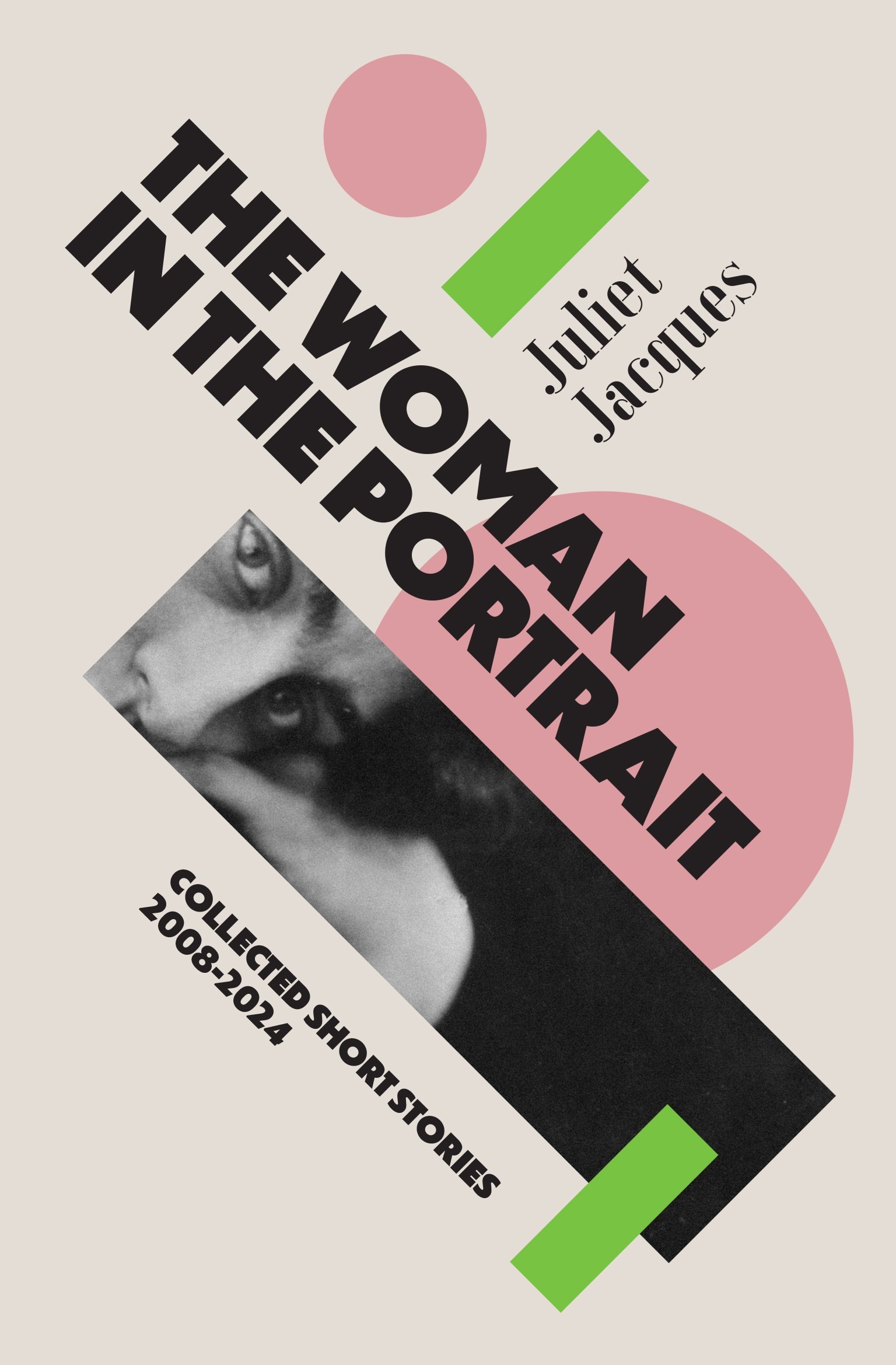

I first discovered the work of Juliet Jacques through a screening of her stirring, soulful film You Will Be Free. I was a few months into my transition and aching for someone, or something, to place my feelings about the world. A series of reflections on queer embodiment and liberation, the film did what art does best: it did not define my aching, it simply spoke to it. Throughout her career, Jacques has demonstrated her unmistakable ability to articulate with poetic subtlety the experience of life on the margins. Her new book, The Woman in the Portrait, a collection of published and unpublished short stories from 2008 onwards, is both a record of this astonishing work and a testament to the communities who each played a part in its creation.

Many of the characters within her stories are, at least ostensibly, living unremarkable lives: in Nazimova, a woman signs a gender recognition certificate as “female”; in A Typical Day, Julia, a trans female office worker gets misgendered during a customer call; and in DCB: A Partial Retrospective, an artist – who was born as David in 1936, and changed her name to Delia in 1963 – has her complete history traced, despite never producing much art, or becoming especially well-known. And yet, from these ordinary conditions, Jacques creates entire worlds that never cease to surprise the reader, nor entertain. Part queer fiction, part socialist polemic, The Woman in the Portrait is a study of the mundane as meaningful, and the personal as political: it is, at its heart, an empowering encounter with society’s most disempowered.

Here, Juliet Jacques discusses some of the key influences and themes behind The Woman in the Portrait.

Alexandra Diamond-Rivlin: The Woman in the Portrait is a book that tours the reader through many different places, eras, political landscapes, situations, and even stages of gender transition. What inspires such rich and expansive world-making in your literature?

Juliet Jacques: The stories touch on gender, sex, sexuality, politics, technology, football, and architecture to some extent, amongst other things. Several of them spring from real-life circumstances, other peoples’ stories, and works of art. It’s often a matter of looking at a scenario creatively and asking certain questions: why write a piece of fiction, for instance, about Christian Schad’s Self Portrait with Model, or French footballer turned Nazi collaborator Alexandre Villaplane, or Dutch conceptual artist Bas Jan Ader? Why write a story rather than an essay or piece of criticism? Usually, it’s because there are questions that come to me that I’m not certain of the answer to, and I don’t think I will ever be certain of the answer to. Fiction is often an interesting way to pose those questions to myself and to a readership.

A lot of the stories in the book are also quite journalistic; there’s one called A Review of a Return that is written as a film review. I write a lot of film reviews, and so I’m certainly interested in the continuity of practice between fiction and journalism as well as the differences. I’ve been interested in the lines between fiction and journalism, particularly as ways of investigating an intriguing set of circumstances that pull on certain social and political conditions.

ADR: One of the places you return to a lot in your work is Brighton. How did the city become a source of creativity for you?

JJ: I grew up in a town called Horley, in Surrey. I found it quite fun to set a few stories around there, too, because the place is so dull and so boring, and as a teenager, I couldn’t wait to leave. A lot of my friends and I moved to Brighton after graduating; it’s where I worked myself out gender and sexuality-wise. Brighton in the 2000s was quite an interesting place. It was rapidly gentrifying; it had a gay scene that was quite different from the one I’d encountered elsewhere; the community was divided into a more butch and femme-gay culture. I spent a lot of time navigating that as a young trans woman and queer person.

There’s a story in the book called A Weekend in Brighton that explores my interaction with the BDSM scene there. The protagonist also works a very boring office job, as I did at the time. I was trying to capture something of Brighton in 2005 – there were these music, film, queer, and sex scenes you couldn’t find anywhere else. It was a really moving experience to access memories that were so buried in my consciousness.

“Something fiction can do is highlight the importance of historical artefacts, historical movements, and so on” – Juliet Jacques

ADR: Something I love about the book is how you draw on archives of radical and queer history. Is there an interesting tension, do you think, between this history as in some way factual, and how it is reimagined by contemporary writers?

JJ: I think the historicisation of anything is an act of invention to some extent. I did a history degree, meaning I am aware of history as a very subjective thing. Something fiction can do is highlight the importance of historical artefacts, historical movements, and so on. The Nazimova story is a good illustration of that; Alla Nazimova may not be a particularly well-known film star today, but has a very transformative effect on the narrator, who is exploring their gender and dressing as a female in public for the first time.

ADR: The book contains stories you wrote at the beginning of your career alongside more recent work. Did you notice any parallels between them that surprised you?

JJ: To get an anthology together, you need a through-line. My publisher Cipher and I spent some time trying to work out what that was. Eventually, we realised that all the stories engaged with culture and the arts, some in looser ways than others. Some of them are examples of ekphratic writing, which is when the story grows out of criticism of an existing work of art. Surveillance City, for instance, is about a journalist in London who gets drawn into semi-public BDSM activity that seriously stretches her boundaries. A lot of the character names have sneaky references to works of erotic, French literature. There’s a reference to one of Guillaume Apollinaire’s erotic novels in there, for example, as well as Alain Robbe-Grillet.

As for the politics of the stories, in some ways they change, in other ways they are consistent. The earlier ones are probably more focused on queer and sexual freedom, whereas once you get near the end of the book, they draw more on the post-Corbyn period in British politics.

“Brighton in the 2000s was quite an interesting place; it’s where I worked myself out gender and sexuality-wise” – Juliet Jacques

ADR: Continuing with this point about the book as a collage of old and new, what does it mean to look back and reflect as a writer?

JJ: It does give you a sense of what’s changed and potentially could change in terms of one’s career and overall approach to literature. We’ve got a different government now, and it’s clear how I respond to that in my writing: I’m just as opposed to the current government as I was to the Boris Johnson administration. I think this supposed shift in power presents an interesting challenge to writers regarding how we’re meant to respond to this new epoch, which in my view, isn’t particularly different from the last.

For the most part, looking back is an opportunity to think about which styles and themes I want to engage with, how politicised I want the stories to be, and in which direction I want them to go. I can see my work moving from a more queer-focused approach to a socialist one. And so I suppose looking back is, for me, an interesting way to not just look at the past, but to think about the future, too.

The Woman in the Portrait: Collected Short Stories by Juliet Jacques is published by Cipher Press, and is out now.