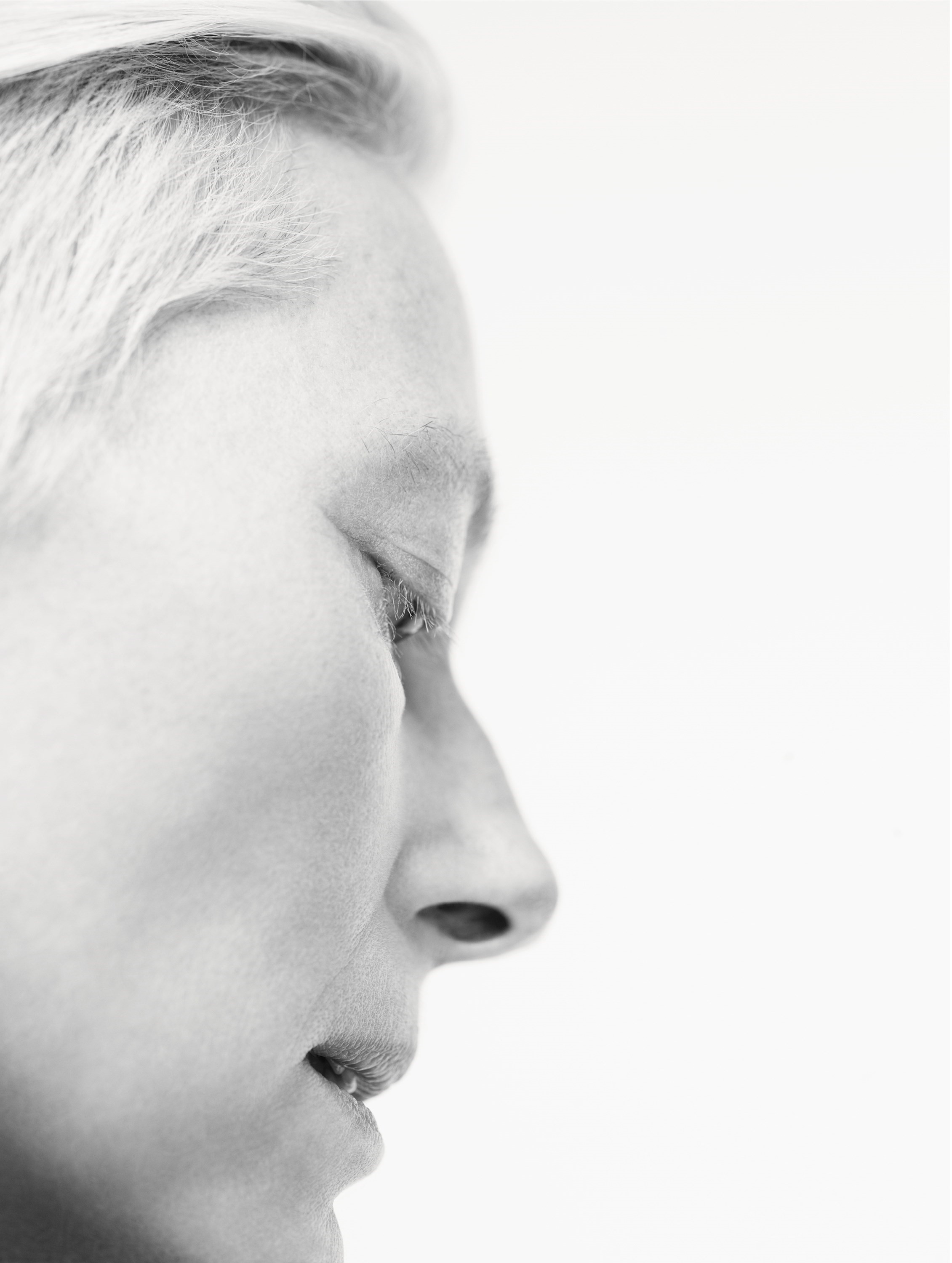

Watching Tilda Swinton being watched, either for still or moving image, is nothing short of bewitching. The actress is so acutely aware of herself and her performative nature that the usual discomfort associated with voyeurism – not so much the idea of remaining unseen but of observing those unaware – disappears completely. That is perhaps because she is deeply, even profoundly, in control of her physical self: of the power of gesture and volumes spoken by silence.

When your art centres around being watched, existence may become part of the performance. That in itself sounds pretentious, but Tilda Swinton is not only one of the most celebrated and talented actresses of our time, she is also the woman who, encased in a glass cabinet at the Serpentine Gallery, transmogrified into a work of art, in a piece of her own conception, The Maybe (1995). Having collaborated with artist Cornelia Parker on the installation surrounding the piece for this London manifestation – the first of three in different cities with different collaborators over following years – it is well known that she was there for eight hours a day, seven days a week; a silent, living sculpture. “Please come and go quietly” read a sign on the wall – “not in deference to authority,” wrote The Independent at the time, “but out of respect for the person whose slight form exerts such an extraordinary power over this room.” She continues to exert just that extraordinary power today.

Swinton wasn’t a star then, rather an avant-garde, indie-film protagonist. Exceptionally, mainstream Hollywood success hasn’t robbed her of that status or of the credibility that goes with it. But when she reprised the piece in 2013, this time at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, it was off the back of a 2007 Academy Award for best supporting actor in Tony Gilroy’s Michael Clayton and the global acclaim of Lynne Ramsay’s We Need to Talk About Kevin (2011). As with each incarnation of the work, Swinton refused to release the times at which she would appear, incumbent; and the piece was still labelled simply with the words “Living artist, glass, steel, mattress, pillow, linen, water and spectacles.”

Swinton has explored the power of silence on film also, in A Bigger Splash – loosely based on Jacques Deray’s 1969 film, La piscine. Directed by Luca Guadagnino, it is their fourth of five feature films together. In it, Swinton is rock musician Marianne Lane. Recovering from throat surgery, she speaks only during flashbacks, dialogue otherwise stripped back to infrequent and appropriately hoarse whispers.

Controlled, concentrated, focused, intense are all words that may be used to describe Swinton’s presence. They also apply to her career, the roles that she has chosen and with which she has defined public perception. They equally go some way towards explaining her relationships with specific directors, whom she returns to work with again and again, rarely severing ties after her films. After Derek Jarman cast her in his Caravaggio in 1986, they collaborated on half a dozen more films, including The Last of England (1987), Edward II (1991) and Blue (1993), which Swinton narrated in part. She was a companion until his death in 1994. She has collaborated repeatedly on films with Wes Anderson, The Coen Brothers, Jim Jarmusch and Bong Joon-ho.

Swinton chooses the people first, not the projects, and her relationship with Guadagnino – with whom she formed the production company Crazy Crazy Crazy Normal Normal Normal in 2017 – is clearly an inspiring meeting of minds. She first came across him when, as an unknown Italian director, he pursued her via her agent in 1994. He then ran into her in Rome later that same year and Suspiria is the latest result of their ongoing conversation – a film about which they have been talking, both confirm, for almost 25 years. This film was written for Swinton – and for her co-star Dakota Johnson – the director says, and it’s difficult to imagine anyone else stepping into the role of Madame Blanc, a tormented choreographer and dancer who has, effectively, sold her soul for her art. There is a dignity to Swinton’s performance in the film, and a fragility that is immensely moving. That Guadagnino loves her is evident as the camera studies her every move.

Swinton is currently between films, preparing for her next identity, a new incarnation – as Miss Betsey Trotwood in The Personal History of David Copperfield, the Charles Dickens classic retold by Armando Iannucci, to be released next year. Away from her career, she retreats to Scotland – to the fishing port of Nairn (population barely 10,000), at the remote peak of the Highlands. It’s more difficult to watch her there.

Susannah Frankel: When did you first see Dario Argento’s Suspiria and what did it mean to you?

Tilda Swinton: I suppose when I was about 20. It was one of those films that, having seen it, I searched for its other fans like a hound after truffles. The colour, the expressionism, the extraordinary soundtrack by Goblin... It could have been a dream. I think Luca was the first person I met who felt the same way about it as I did. Since then, of course, I have found many more.

You have been talking with Luca about Suspiria for a long time. When did you begin that conversation?

We have been discussing and planning Suspiria since we first met, nearly 25 years ago, for as long as I can remember.

You attach great importance to your relationships with collaborators – the people regularly come before the project. How has your relationship developed?

This is the fifth long film we have made together, not counting several shorts. We are constantly working on something or, rather more accurately, various things concurrently. We met in 1994 and have been friends and playmates from the very first. Now we have a company together. In the most important ways, nothing has changed. But we’ve grown the family album, so to speak, have been on many holidays and adventures together, have deep roots.

Luca has referred to the project as both an homage and a reimagining. How do you relate to that idea, and therefore to the original?

The impulse to make this film in the first place was born, in each of us in turn, as we began to work on it over the years, out of a deep affection for Argento’s classic. This admiration is a great original bond, as with all fan groupies, always. And our fresh fantasies that grew out of this love of Dario’s film bloomed into ours as a cover version of the Suspiria of 1997. Who knows? There may be more covers ahead. As we know from music, many ‘covers’ sound very different from the original song. But the love is always the motor, however different a context, a time, the fresh approach sits in. You can’t very easily commit yourself to the cover of something that you do not fancy pretty hard.

Madame Blanc is a great artist but a person who has chosen a difficult path. Do you see her as fragile because of that? Would you say she has chosen the wrong path?

Blanc is the artist in among the witches. She is a dancer and choreographer of rare and groundbreaking genius, a charismatic and powerful teacher who inspires real devotion in her dancers, and her conflict is a genuine one. She has bartered with the supernatural for the sake of the perpetuation of her company and must live on the knife-edge between the two. Ambivalence and a sort of twilit loneliness hang about her. The expressive power of dance, of art, is her true power. She knows herself to be deeply compromised by the witchcraft she deals in. The brutally traumatised context of the Berlin she has survived and is living through still – its barely suppressed war-woundedness – is an alienated and alienating one. Beautiful and cheerful, she tells Susie, are not possible options for dancers any more – “We must break the nose of every beautiful thing.”

There’s a fearlessness to your approach – to challenging conventions in your fields. Do you feel it’s important to break rules? Transgress boundaries?

I don’t really recognise a particular fearlessness in myself. Maybe I simply have an extremely low boredom threshold and want to keep myself amused by putting things into play that I haven’t seen before. At any rate, the process is the element that interests me the most, the fellowship of chewing the cud of a project with my partners. This is what keeps me making films and what continues to draw me back, time and time again, to performing in them. The game of it. It tickles me. Meanwhile, I’m not really aware of any particular set of rules to either follow or break when making art, to be honest.

How important is the concept of motherhood in Luca’s Suspiria?

It’s central. Our Suspiria is crucially occupied with the particular psychic atmosphere around motherhood. It draws heavily on the wisdoms of Erich Neumann’s seminal Jungian analysis set out in his book The Great Mother.

In examining the archetype of the Great Mother, Neumann explores not the concrete or the manifest but the inward image of the mother at work in the human psyche – the struggles that the unconscious suffers in relation to the energies and emotions evoked by projections of the Great Mother. We place into our narrative the triangular energetic pulls between the ego – the artist Blanc; the super ego – the analytical psychiatrist Klemperer; and the id – the witch sorceress Markos. The film seeks to amplify this pull, to set out a web of power plays around our young women, Patricia, Sara, Susie and the rest. Susie’s mother is dying – Susie seeks a new paradigm. She finds in Blanc, as do all the dancers, a warm and loving authority – a Good Mother – under whose influence she appears to feel relieved to subordinate her will. Meanwhile, for Blanc, Markos – the Terrible Mother – exerts a tyrannical influence that infantilises and destabilises her self-possession. The tussle between these two archetypes signifies what Neumann identifies as the ambiguity within the feminine. Of course, there is always a third way.

It’s a very different film, on the surface, to Call Me by Your Name – more tough, perhaps, more dark, certainly. Still, there is a deep vein of compassion running through it. Would you agree and, if so, how is that expressed?

There is, I suppose, a large audience that only knows Luca’s work due to the widespread embrace of his last film, Call Me by Your Name. That wider audience may be surprised by Suspiria – as many of those familiar with his earlier work maybe were by Call Me by Your Name – but those of us who know him well would say that this film is possibly the most authentic expression of Luca’s authorial voice so far. This Suspiria sprang out of an inspiration that was born in him as a very young person. In many ways, his response to Dario Argento’s Suspiria was the initiation of his fantasy of himself as a film director.

It is pretty much an all-female cast. Would you describe Suspiria as a feminist film?

I would describe the film as populated by humans and absolutely humanist to its core.

In the first poster for the film, the second-wave feminist slogan “TREMBLE TREMBLE!! THE WITCHES ARE BACK” is used. Why? Why is that important?

The innate significance to the psyche of wild women, of wise women, of devouring mother figures, from Kali in India to the Gorgon everywhere, the child-stealing Rangda in Bali to the snake goddesses of Greece, is profound and innate. The power of the feminine and its awesome shadow potential is unassailably accepted throughout human culture across all continents and millennia. It’s important to look at the dark stuff. Our ability to envisage the light depends upon it.

The film centres around a coven of witches. Historically and symbolically, what does that mean to you?

I live not far from the village in the Highlands where the last witch in Scotland was burned, less than 300 years ago. Closer still, a mile from where I live, a woman called Isobel Gowdie – a gifted storyteller and charismatically self-possessed – was burnt at the stake, having “confessed” to myriad acts of “witchery”, from transforming herself into animals to fucking with the Devil and every exciting thing you can imagine in between. I find this pretty compelling, the narrative that runs consistently through our constantly molten ‘civilised’ culture, the frequent suspicion and distrust of the intelligence of women and the attempts to suppress their ‘magick’ in the name of the rational.

Your Suspiria is set in West Berlin in 1977, the year the original Suspiria came out. The Baader-Meinhof Group is omnipresent. How much do you remember about the movement?

I first went to Berlin in 1986, a little later than the year of the film, but close enough for me to recognise and attest to the particular landscape of those pre-unification years. The sense of limbo – and of palpable ‘post-war’ status – was extremely powerful in those days. The pulse of violence very close to the surface, peaceful tracks only newly laid. I remember the Baader-Meinhof years only vaguely as a child, but I do remember asking my father about them when I saw their pictures in his paper and him telling me that they were fighting their own war – a choice of words that made a great impression on me, since my father was a soldier himself and because I detected a measure of respect in his attitude.

You’re always smoking in the film, is that a reference to Pina Bausch? Is she an important cultural figure for you?

Pina Bausch was, and continues to be, a properly vibrant artist in my consciousness. I first saw her work in the Eighties. I never met her, but she was a close friend of my old sweetheart Christoph Schlingensief, so I have always considered her kind of extended family. We looked at a number of influential dance artists of the time, Pina clearly being one of them. However, I would have to say that probably my most radical influence in putting together the Mme Blanc character in our film is that of Mary Wigman, who was a seminal figure in the development of expressionist and ‘existential’ New Dance in Germany from before the second world war. Perhaps her most iconic creation is the Hexentanz, or Witch Dance, which Damien [Jalet] and I referenced quite literally in gestures we designed for Blanc. Also, a certain mental fragility in tandem with the controversial and distinctly compromising survival of her company under the Nazis make Wigman a vivid early model for Blanc.

The smoking – Suspiria being about breath, about inhalation, it felt inevitable that Blanc would be constantly drawing on a fag. The masochism of it appealed to me in putting together her picture and, somehow, an adolescent wilfulness in the gesture, a kind of permanent resistance, rebellion, but you are quite right, there is hardly a picture of Pina without a cigarette in her mouth or hand. It just made it feel right to quote that element.

Horror is a genre that divides people. Why do you think that is? And how do you react to horror films?

To good and profound horror – to The Exorcist, to Rosemary’s Baby, to The Innocents to Don’t Look Now, to The Shining to The Thing to Bong Joon-ho’s The Host to I Saw the Devil and many, many more – with gratitude and glee for the catharsis and the life force they encourage in us.

[The Slovenian philosopher] Slavoj Žižek reminds us that we need the cinema in order to learn what we desire – maybe we need horror films to learn what we fear. I suppose the primary issue is whether you mind being frightened or not. Some people – I happen to be one – like the sensation of having survived the horrors of a good terrifying film. Not everybody feels the same.

The ideas in the film are extremely complex and layered. How much of this is for you as a performer and how much is for the audience?

All work is layered, whether we detect those layers or not. Artists make work out of our own lives and times and interests and efforts. It’s a tall order to rely on every nuance of the inner history and life of a piece of public work to make itself recognisable and found resonant by everybody – or even anybody – who sees it. There’s only so much you can allow yourself to mind about when you give work away into the world.

How would you like Suspiria to be perceived?

Pass.

How would you like your character to be perceived?

Triple bypass.

What are you afraid of?

Essential humane kindness abandoned in any circumstance. Doubtlessness. Losing my specs – something I have just managed to do today and will endeavour to survive nonetheless.

Hair: Anthony Turner at Streeters. Make-up: Peter Philips using Dior. Manicure: Ama Quashie at CLM Hair & Make-up using Dior manicure collection and Capture Totale Nurturing Hand Repair Cream by Dior. Colourist: Amy Fish at Larry King Salon. Digital tech: Henri Coutant. Lighting: Romain Dubus. Photographic assistants: George Eyres and Robert Willey. Styling assistants: Niccolo Torelli, Francisco Reis and Letizia Maria Allodi. Seamstress: Gillian Ford. Hair assistant: Claire Grech. Make-up assistant: Kathinka Gernant. Producer: Laura Oughton at Rosco. Production coordinator: Danny Needham at Rosco. Production assistants: Juliette Dumas and Michel Bewley. Post-production: Triplelutz.

This full story originally featured in the Autumn/Winter 2018 issue of AnOther Magazine which will be on sale internationally from September 13, 2018.

Correction: The article originally printed in the Autumn/Winter 2018 issue of AnOther Magazine misidentified the author of artwork The Maybe (1995), as Cornelia Parker. The work was in fact concieved solely by Swinton, though she worked with the artist, Parker, on the installation for the Serpentine Gallery. The piece's later incarnations at both the Museo Baracco, Rome, and MoMA bore no connection to Parker. It also erroneously stated that it was under MoMA's direction that the performance times were not revealed; this, rather, was a device employed by Swinton for each iteration of the work.