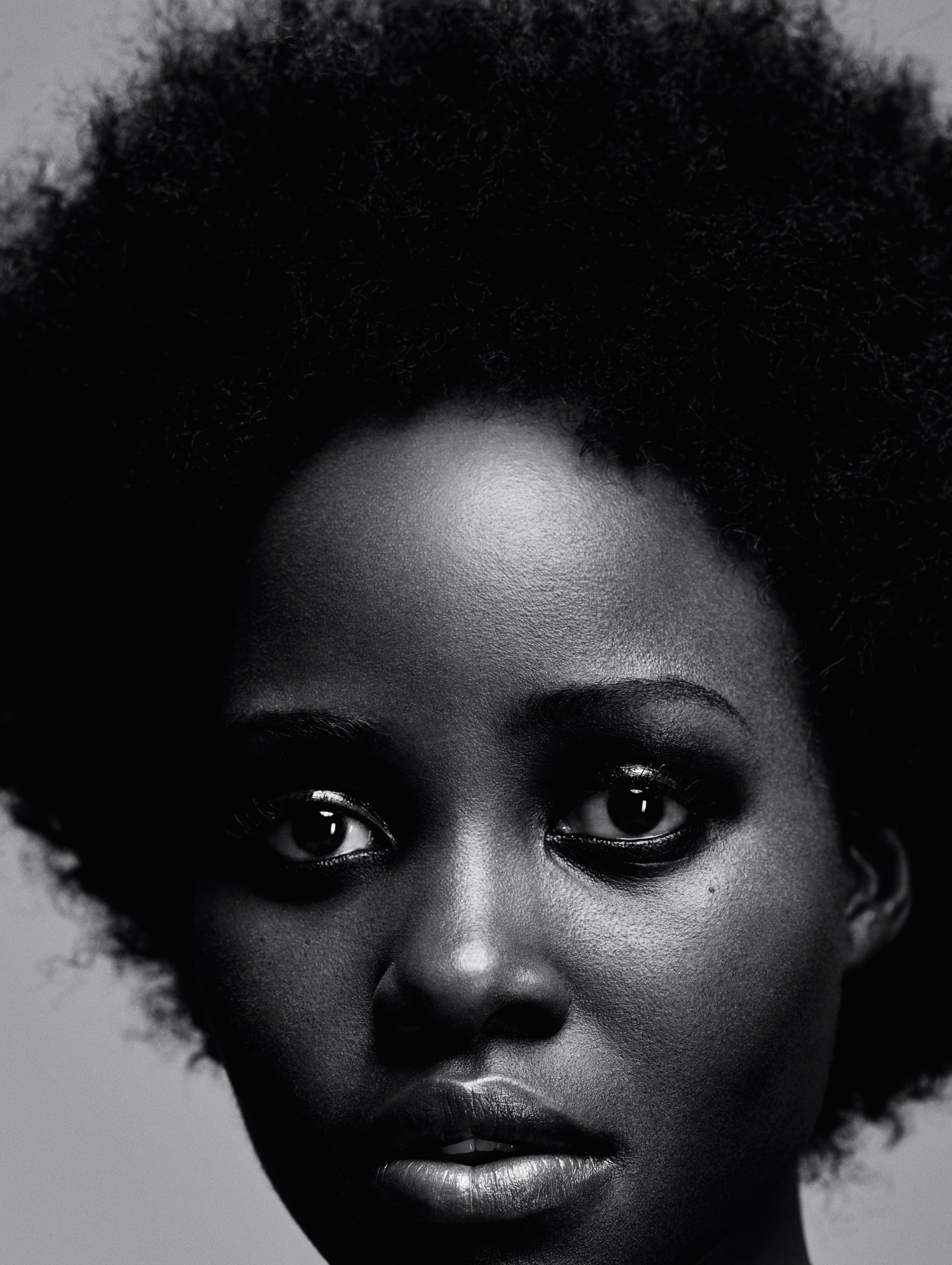

It’s been just six years since her Oscar-winning turn as Patsey in 12 Years a Slave but Lupita Nyong’o has already redefined what screen actresses might be, what they might achieve, what they might represent, and how they might inspire others. In fiction, she has inhabited different worlds, told different stories. In reality, she has affirmed the beauty of millions of black women across the globe, reaching way beyond the limitations of cinema.

Last year, as special-forces operative Nakia in Ryan Coogler’s Oscar-nominated Black Panther, Lupita Nyong’o and her accompanying all-black lead cast – unprecedented in the superhero-movie genre – caused a seismic shift. Marrying the black experience, which in Hollywood is rarely seen through the African lens, with fantasy fiction, the resultant epic carries an enormous cultural significance that will be its legacy. It was wildly popular: Black Panther was the ninth-highest-grossing film of all time. 2018 also saw Nyong’o reprise her performance as Maz Kanata in the Star Wars franchise, due for release later this year. Both roles – pivotal to megawatt, mega-buck productions – transcend any vague notion of Nyong’o as an ingenue, a rising star. In fact, later this year she will take her place alongside Hollywood’s greats on the Walk of Fame. Despite such acclaim, when we meet in December she is remarkably private: wrapped, understated, incognito in a black coat, deep bucket hat and scarf, in a somewhat sleepy part of Clinton Hill, Brooklyn, where she lives. Those interviewing Nyong’o in person are asked to speak to her on the telephone beforehand because, as her publicist explains, “she likes to get to know more about you” – and to understand where the conversation might lead. As it turns out, she’s researched me almost as much as I have her.

We settle at a corner table. Nyong’o describes a hectic week flying in from Los Angeles for interviews then flying back to her native Kenya for the holidays. Her beauty is luminous – regal – a quality only added to by her notorious intensity. She speaks in hushed tones, calm and considered, forgoing some of the menu’s elaborate offerings in favour of a herbal tea.

The new year sees Nyong’o expand her repertoire in a manner that will broaden her appeal still further. In March, she returns to the screen as the female lead in Jordan Peele’s Us. The film leans into the genre that made his directorial debut, Get Out, so successful and, according to the director, will be the second in a five-movie series of social thrillers. Nyong’o herself is reluctant to reveal too much, as was Peele, who had only teased with leading one-liners on social media until, on 25 December 2018, he released the first trailer. His audience now knows that Nyong’o joins her Black Panther co-star Winston Duke, as Adelaide Wilson and husband Gabe respectively, on a road trip with their two children, during which she is confronted by a past trauma that unlocks a terrifying series of events. Elisabeth Moss and Tim Heidecker bolster a major cast. Nyong’o describes Us as a “scary, intense, mind-bending WTF kind of story”.

“But that’s why I wanted to do it. I mean, I’d walk off a cliff for Jordan Peele,” Nyong’o says now. “I was madly in love with the mind of Jordan from the Key & Peele days, and I remember putting him on my ‘one day I’ll work with’ list. Then I saw Get Out. I saw it in the cinema five times in one month. I was just so fascinated by it. Then he approached me to do this film. He sent this script – I’m usually very slow at reading scripts. He sent it to me and in 24 hours I knew I would be insane to pass it up.” In true Peele fashion, Us promises a story that makes people look at themselves psychologically, socially and culturally, through the horror genre. Or, as he himself puts it: “We are our own worst enemies.”

Lupita Amondi Nyong’o was born in Mexico City in 1983, to father Peter Anyang’ Nyong’o, now a prominent Kenyan politician, and mother Dorothy Ogada Buyu Nyong’o. Her father had left Kenya for Mexico City three years prior as a safety measure due to the murder of his brother Charles: both were passionately opposed to the oppressive regime of Daniel arap Moi (president from 1978 to 2002). Her mother returned to Kenya with the children when Nyong’o was one year old. “I come from a big family [she is the second of six siblings] and I’m really close to my extended family,” she says. “I remember my childhood as being very vibrant, spending Sundays at one of my cousin’s houses and walking to the pool club – we’d spend all afternoon swimming and eating chips and sausage. Growing up, there was lots of noise, there were lots of people, lots of options.”

“I’d walk off a cliff for Jordan Peele. I was madly in love with the mind of Jordan from the Key & Peele days, and I remember putting him on my ‘one day I’ll work with’ list. Then I saw Get Out. I saw it in the cinema five times in one month. I was just so fascinated by it” – Lupita Nyong’o

Later, her father returned to pursue his academic career. Nyong’o remembers this time, at which point, encouraged by her aunt, she began discovering and nurturing her creative streak, “performing little skits for our family gatherings and things like that. I loved how seriously she took it. I got to play in a made-up world and we all got to take it seriously, you know? I enjoyed that I was choosing my reality. It all started from that. From there I realised there was a seduction to it. I enjoyed the power that it gave me over my parents for the brief moment that I was the one in charge of the story. My father would tell extravagant stories, my grandfather, too, so I always had these different ideas of what imagination might be.”

At 16, Nyong’o went back to Mexico City on the insistence of her parents, “who felt that I should be able to speak the language”, she says. “I think they were always intent on me learning Spanish because, before they left Mexico, they bought all these children’s books. And I had a foreign name, Lupita [a diminutive of Guadalupe]. I was always aware of this other place where I quote-unquote ‘belong’. That always gave me a badge of honour, I suppose, but also a curiosity. My parents thought if I had the passport I might as well speak the language.”

A personal lack of confidence, paired with societal and familial pressure, meant Nyong’o studied the mechanics of film rather than the craft of acting in the first place. She graduated with a film and Africa studies degree from Hampshire College in Massachusetts. “I definitely had aunts come to me and say, ‘When are you going to do something serious?’ It came from ignorance and it came from love and from fear. I understand that now, but the reason why none of that ended up being my story is because my immediate family was very supportive, I have very unconventional parents who supported all of our interests. They figured out what we were interested in and they would encourage it, without any regard to how it might one day be monetised.”

While at college, Nyong’o circled acting, working as a production assistant on film sets. Back in Kenya, on location for Fernando Meirelles’ 2005 Oscar-winning The Constant Gardener, a chance conversation with Ralph Fiennes proved the catalyst that put her on the direct path to the other side of the camera. “I was having lunch with Ralph one day and he asked me about my interests, and I told him that I wanted to be an actor, I think. He said, ‘Only do it if there’s nothing else you want to do, if there’s nothing else you feel you could do.’ It wasn’t, ‘Here’s my number, I’ll be your mentor.’” She laughs. “It wasn’t that but he gave me a lot of food for thought.”

In 2009 Nyong’o returned to the US to attend Yale School of Drama’s three-year programme – Meryl Streep and Frances McDormand are both alumni – filling one of its few highly sought after places. Even before that, in 2009, she accepted a leading role in an MTV series, Shuga, that followed the lives of a group of teens in Nairobi, Kenya. “It happened right after I got accepted to Yale, so that was on the cusp of deciding to really pursue acting as my priority.”

What happened next is the stuff of Hollywood folklore, a scenario more likely to be played out on screen than in real life. Immediately after graduating, and still without an agent, Nyong’o met, auditioned and was cast by director Steve McQueen, who had long been searching for an actress to play the role of Patsey in his film 12 Years a Slave. While many may have wilted at the sheer scale, Nyong’o remembers thinking, “This is not about, ‘Is this what I am or am not meant to do?’ It was really about rising to the opportunity that had been given to me and making sure I didn’t sabotage it with the fear that I felt stepping out into this big bad world. The size, the people, the history of cinema and American history – I needed to not psyche myself out of it and actually do the thing that I trained for three years to do and I loved to do. The film was a utopic experience, in terms of having an incredible director, an incredible script, an incredible cast and a quite joyous set experience, despite the subject matter.”

“When I think what Black Panther has done for Africans and Africans in their diaspora, it’s this allegorical story about the relationship between Africa and America, reflected in the relationship between T’Challa and Killmonger. It’s a chance for both to consider each other’s perspective in a way that I don’t think popular culture has been effective at doing. It’s really the start of a long-overdue conversation. In no way does it call for answers, but it’s the opportunity to begin to recognise what it is we have in common” – Lupita Nyong’o

And despite this being her debut feature film, the performance in question cemented her place, earning her the 2014 Academy Award for Best Actress in a Supporting Role. She is only the sixth black actress and the first African actress to achieve this. Since that time, the eyes of the world have been on Lupita Nyong’o. “Different people would say, ‘This is your moment, this is your moment.’ That was kind of perplexing,” she says today. “What does that mean? What does that mean in actual practice? I had to really sit with myself and figure out what I wanted my life to look like. There was the expectation that, when your career explodes, the world is at your feet, you can have anything you want – that’s the Cinderella version of it. Then there are the real questions – ‘What do I have an appetite for now? What does success look like to me? Now that I’ve achieved all this, what does failure look like?’ I really needed to define those three things, not on the world’s terms but for myself. For me, success equals longevity, success equals the luxury of choice. Even when I was in school, they were always preparing us for whatever came our way. We were not honing our skills at choosing what we wanted to act in, we were honing our skills at making a meal out of whatever little got thrown at us. So, if you were playing cop number three you could still find the joy, the life, humanity in that, because it is expected that it is a long road to roles of substance in the industry. They’re not really training you for instant success and choice. That’s what the accolades that came with 12 Years gave me – they afforded me a choice.”

That choice came in the form of her role as Maz Kanata in JJ Abrams’ Star Wars. A thousand-year-old computer-generated pirate, both voiced and performed through motion capture by Nyong’o, it was a decidedly left-of-field option following that of the heart-wrenching heroine of 12 Years a Slave. “It was a perfect situation for me,” Nyong’o explains. “Star Wars came along and offered me an experience outside my own body, something that doesn’t come along very often for an actress – a role that does not require the perception of your body. And I needed that at that point. I wanted to retreat into my path because I was still navigating this thing called celebrity and nobody really explains that to you – there’s no course you can take on how to handle it, the recognition and all that. So, what Star Wars gave me was a chance to do the thing I love and not be seen doing it. Though Star Wars was not part of my everyday existence, it has defined American pop culture.”

There followed 2016’s releases of Queen of Katwe (Nyong’o played Harriet Nakku, a young mother in the Ugandan slum named in the title) and the remake of The Jungle Book (voicing Raksha, a female Indian wolf). That same year, she began preparing for her role as Nakia in Black Panther.

“I was on a panel two days ago with Hannah Beachler who did the set design,” Nyong’o says. “She spoke about how not only is she African-American and a descendant of slaves but she’s also adopted. So, she said, her past begins and ends with her. What this film gave her was a chance to heal herself in a sense, to reclaim a sense of history by creating a history for a people that does not exist. That was a powerful statement and we were all in tears. When I think what Black Panther has done for Africans and Africans in their diaspora, it’s this allegorical story about the relationship between Africa and America, reflected in the relationship between T’Challa and Killmonger. It’s a chance for both to consider each other’s perspective in a way that I don’t think popular culture has been effective at doing. It’s really the start of a long-overdue conversation. In no way does it call for answers, but it’s the opportunity to begin to recognise what it is we have in common. It’s like in the Sixties, with the pan-African movements, the leaders of the continent coming to study in America. [Kwame] Nkrumah meeting with Martin Luther King Jr and Malcolm X – there was a real exchange happening. I think there is a re-visitation of that kind of conversation – our histories are intertwined, whether we care to see it or not.”

With that in mind, Nyong’o’s next step is natural if no less ambitious. She is taking on the screen adaptation of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah, which she will both star in and co-produce (alongside Brad Pitt’s production company Plan B Entertainment). Nyong’o hounded Adichie for the rights for years. “In fact, just before 12 Years came out,” Nyong’o clarifies, she made that first approach. “I pre-ordered that book and I could not put it down. To see an African woman whose identity was in a flux in the way that Ifemelu’s is in the book just spoke so deeply to me. I could not stop thinking about it so I immediately contacted her. I had no stars or stripes to my name except, ‘I’m an actress from Kenya and I read your book and I love it and I’m going to be in this movie called 12 Years a Slave.’ I had no idea what that meant anyway, but I knew I wanted to make this.”

Of course, once 12 Years a Slave came out to unanimously rave reviews, Nyong’o had more traction. Then, producers were interested in working with the actress – which helped with obtaining the rights. Close friend, actress and playwright Danai Gurira is now tasked with transforming Americanah into a mini-series. Because, as Nyong’o explains, “It’s very hard to reduce just to a movie. We discovered that, while we were trying to adapt it, we needed more time. It’s been a long journey with Americanah, but I feel like projects come to be in their own time, in their right time. We’re very near, we’re so close to a production date and that’s really exciting.”

“I know that every time such an opportunity comes my way, it is changing the narrative. I can play the role that someone like Alek Wek played for me growing up. Every time someone shares their experience of how I might have affected them, I’m very happy for that, but I don’t do it for the symbolism. I think the thing that’s steering me forward is not to be a symbol, it’s to be active” – Lupita Nyong’o

If Americanah raises many of the same concerns as Black Panther, it is ultimately domestic, though epic in scale. I ask Nyong’o whether the more sobering topics of the latter – race relations, self-identity, the erasure of black identity through diaspora communities, all of which are explored throughout so much of her work – were made more digestible couched as a Marvel Comics blockbuster. “You mustn’t underestimate the power of story. What this Marvel ‘casing’ did was make it accessible, make it popular, make it palatable. That’s the power of a truly great story. Really, these tales of superheroes are part of modern-day folklore. As human beings, we all gather around stories. Stories are the one thing we can never get enough of because it’s the way in which we really come to terms with who we are, who we’ve been and who we’re becoming. It’s powerful, it’s meaningful, it’s really potent. That’s why a Marvel film can cause such an effect, such a spark in these schools of thought. It’s safe to walk into a Marvel movie – then you serve them a dish of some realness and they’re more prepared to eat it. That just gives more power to Ryan [Coogler] to tell stories from a visceral place. Ryan does not know how to lie and so he tells his truth, and this story was his truth. It was him grappling with his own relationship with identity, his own relationship with the continent and trying to make sense of it.”

Nyong’o’s beauty has similar potential and power. She is among the long-time ambassadors of Lancôme, has fronted both Calvin Klein fragrance and Tiffany campaigns and has graced the cover of American Vogue four times. Her success is arguably an anomaly in an industry that notoriously puts women of colour in the backseat, particularly those of a darker complexion. Nyong’o has been vocal about her own path to self-acceptance, particularly in a now-viral speech at the Essence Black Women in Hollywood event in 2014. I ask her if she feels the weight of a million unheard women on her shoulders. “I’m not weighted by it at all. I’m inspired by it. I know that every time such an opportunity comes my way, it is changing the narrative. I can play the role that someone like Alek Wek played for me growing up. Every time someone shares their experience of how I might have affected them, I’m very happy for that, but I don’t do it for the symbolism. I think the thing that’s steering me forward is not to be a symbol, it’s to be active.”

That activism transgresses boundaries of race, empowers women globally. In October 2017, Nyong’o was among the most prominent industry voices and the first woman of colour to rise up and condemn now-disgraced Hollywood mogul Harvey Weinstein, recalling her experiences of harassment at his hands while still a Yale student in 2011. Her admonishment came via a 3,000-word op-ed published in The New York Times. “Now that we are speaking, let us never shut up about this kind of thing,” she wrote. “I speak up to make certain that this is not the type of misconduct that deserves a second chance. I speak up to contribute to the end of the conspiracy of silence.”

Serving as another medium to communicate meaningful – personal – messages, Nyongo’s other writing bears mention. An upcoming children’s book follows protagonist Sulwe (‘star’ in Nyong’o’s native language, Luo) who, frustrated with the skin she’s in, goes on a journey to try to alter it. “Then, one night, she goes on this magical adventure that shifts her perspective of herself. It was because I wanted that message to be received by a child before the world has told them, ‘You’re not good enough.’ That is at age four or five, before you’d be interested in listening to that kind of speech. I am extremely proud of it, of the power of what it will be.”

We discuss star signs: she’s a Pisces, known for compassion and having an artistic, intuitive and, at times, tactical nature. It’s accurate. Nyong’o is laser-focussed: though she relishes precious time with her niece back in Kenya she is obviously set on a course that takes up a lot of her time. “I really want a hobby, something else to be passionate about, but nothing holds my interest. I think that’s why I’m an actress, because I really enjoy intensely focusing on something for a period of time and then letting it go. I sometimes think of what I do and, to all intents and purposes, I don’t have a ‘proper’ job. I’m hired for a few months and then I’m fired, and I have to go and find a new job. I have the job of an actor and I have the job of a celebrity, and those two jobs are very different from each other,” she says. She wraps her coat around herself, signalling it is time to go on to her next appointment. “But if I’m doing stuff that is making a difference, to me and to the world, then that’s valid, I think.”

Hair: Lacy Redway at The Wall Group. Make-up: Aaron de Mey at Art Partner. Manicure: Yuko Tsuchihashi at Susan Price NYC. Digital tech: Henri Coutant. Lighting: Romain Dubus. Photographic assistants: Stefano Ortega and Aaron Lippman. Styling assistants: Niccolo Torelli, Eugenia Gamero and Jose Miguel Dao. Hair assistant: Quilla. Make-up assistant: Tayler Treadwell. Production: One Thirty-Eight Productions. Production assistants: Emma Sparrow, Tom Hennes and Luis Jaramillo. Special thanks to Stephanie Jaillet and Eliza Allenbach at Triplelutz Paris.

This full story originally featured in the Spring/Summer 2019 issue of AnOther Magazine which will be on sale internationally from 14 February, 2019.