Lily James is much more than an English rose. The actor, most famous for a litany of leading roles in period dramas, straddles generational appeal: she is as at ease as a teen pin-up as she is playing a beribboned, bonnet-clad aristocrat, a mobster’s love interest or Cinderella. Her forthcoming turn as the second Mrs de Winter in Ben Wheatley’s remake of Daphne du Maurier’s gothic tale Rebecca promises more accolades – adding to those from directors including Danny Boyle and Edgar Wright. Having made bold and fresh acting choices spanning eras and genres, James is a talent intriguing an audience who wish to know more.

It is endearing how openly the actor Lily James bears her insecurities – with an assured self-acceptance nonetheless. “When I’m a bit nervous and don’t know what to say, I go very jolly hockey sticks,” she says. We’re driving across London, from Walthamstow to her dinner date in Soho; she talks animatedly, waving her hands and darting off on tangents as we’re jostled about on the back seat. “I sound like a boarding-school girl who’s 15 years old and has midnight feasts. It’s like a security blanket – I just become some sort of caricature. Sometimes I think, ‘Lily, for God’s sake, what’s wrong with you?’”

I’m reminded of a scene from Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca, the romantic psycho-thriller famously translated for cinema in 1940 by Alfred Hitchcock. James stars in director Ben Wheatley’s new adaptation of the novel that hits screens later this year and there’s an uncanny resemblance between the actress at this point and her character, the second Mrs de Winter. In the book, the unnamed narrator rehearses a farewell with Maxim de Winter, her soon-to-be husband whom she fears she may never see again, after they fall in love in Monte Carlo.

“‘Well,’ my dreadful smile stretching across my face, ‘thanks most awfully once again, it’s been so ripping … ’ using words I had never used before. Ripping: what did it mean? – God knows, I did not care; it was the sort of word that schoolgirls had for hockey, wildly inappropriate to those past weeks of misery and exultation.”

Like de Winter, James’ boarding-school bravado and her frolicsome filmography – spanning a sparkling Disney Cinderella and a kung fu-fighting Elizabeth Bennet – belies someone more capacious. And in the same way, Rebecca makes perfect sense as a film choice for James at first glance: 1930s costumes and a manor house on the Cornish coast; exquisite production design; and the story of both a new marriage and an aristocratic household haunted by the late lady of the house. It seems hardly distant from Just William and Downton Abbey, her first ventures on screen, the latter of which hurtled James into the spotlight. But in Wheatley’s hands it’s fair to expect a hyperreal and psychedelic telling of du Maurier’s evocative and hysteria-fuelled gothic tale.

“I found it really hard to let the second Mrs de Winter go... I’m definitely an insecure person and the character is so deeply insecure that playing her preyed on my own insecurities. But that was quite an amazing dichotomy” – Lily James

Wheatley boasts a back catalogue of darkness. The (very) black comedy Sightseers, the English Civil War-set psychological thriller A Field in England, and an adaptation of JG Ballard’s dystopian novel High-Rise, set in a luxury brutalist tower block, have all marked the director as an auteur with a diverse but always-disturbing style and a penchant for the contours of both the British landscape and its society, urban and rural. Rebecca marks a cornerstone for James – not only for her CV, which brims with bright and bubbly heroines, but emotionally, too. “I found it really hard to let the second Mrs de Winter go,” she says. “God, the inner workings of her mind. She’s in such conflict, such turmoil. I started having real panic attacks. My heart would beat so fast. For a while after filming I felt unsettled and discombobulated. It’s certainly the role I’ve inhabited the most. Even talking about it, I get kind of breathless. It’s crazy. It was a really powerful experience. I’m definitely an insecure person and the character is so deeply insecure that playing her preyed on my own insecurities. But that was quite an amazing dichotomy.”

James stars opposite Armie Hammer as a dashing Maxim – “he’s a proper movie star, he has this statuesque physicality” – and Kristin Scott Thomas as the menacing housekeeper, Mrs Danvers. “You realise when you read it again that it’s so fucked up,” says James. “My character chooses to support this man who murdered his first wife – we have to play all that really carefully. In the book, the narration gives you the complexities of it all, but it’s still a challenge to tell that story now, in the era we’re in. How do you relate to the second Mrs de Winter? Or do you relate more to Rebecca? Who’s the villain in this piece?”

Born Lily Chloe Ninette Thomson, James always wanted to act. There was no epiphany, rather a quotidian urge ignited by a creative upbringing in Esher, Surrey. It’s the stuff of a sparkling six-part BBC adaptation for television, simmering with white British nostalgia for picnics and Enid Blyton: James studied musical theatre at Tring Park School for the Performing Arts in Hertfordshire, before taking a place at Guildhall School of Music & Drama. The latter came just weeks after losing her thespian grandmother, while her artist-entrepreneur father died during the third term of her first year: they were two of her greatest influences. It’s a tale of heartbreak, the Home Counties, and school lunches in a 17th-century Christopher Wren-designed mansion – but it is the making of an actor with extraordinary emotional depth and empathy.

James takes her stage name from her father, James ‘Jamie’ Thomson, whose life followed an unconventional path. He started out as an actor living on Sunset Boulevard in the 1970s, playing romantic leads in films until a horrendous car crash and the ensuing scars saw him swiftly leap to gangster roles, notably in 1979’s A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square, alongside David Niven. From there he became a musician, playing bass guitar in a pop/rock band called Two Way (with the actor Anthony Head) and, later, a savvy businessman who devised one of the first FaceTime-style programmes for global business. Her grandmother Helen Horton – whose many acting roles included the forceful voice of Mother, the computer in Ridley Scott’s Alien, and a stint as Blanche DuBois in Laurence Olivier’s touring production of A Streetcar Named Desire (taking over from Academy Award winner Vivien Leigh) – was “an actress through and through”, says James. “She was so glamorous, really beautiful … she acted all the way through her life, and when she got shaky, she did radio and audiobooks … As a person, she was just actressy – she embodied it, there was a dramatic flair about her. She wasn’t in plays when I was alive, but I would watch her on TV and in movies.”

“It’s funny because I wasn’t always the English rose, I didn’t play those roles at drama school, or in my first theatre job. Over time, I’ve sort of morphed into a version of myself that I’ve been cast as” – Lily James

James’ career bloomed rapidly after she left drama school, in fairy-tale fashion – ”I started working immediately and I haven’t really stopped,” she says – in large part thanks to her first English Rose role. James played Downton Abbey’s rebellious, curly-haired blonde Lady Rose MacClare on screens across the globe for more than three years from 2012. Her first film role followed soon after – another blonde – in Kenneth Branagh’s Cinderella, alongside Game of Thrones star Richard Madden (James would join Madden under Branagh’s directorial eye again as Juliet to his Romeo at the Garrick Theatre in the West End in 2016). A slew of stints as literary heroines followed, including the fearless and principled Bennet in Burr Steers’ wry Pride and Prejudice and Zombies opposite Sam Riley, and the naive and loving Natasha Rostova in the BBC adaptation of Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace. Earlier stage roles as Desdemona in Othello and Nina in Anton Chekhov’s The Seagull meant James’ status as classical ingénue was assured.

“It’s funny because I wasn’t always the English rose,” says James. “I didn’t play those roles at drama school, or in my first theatre job. Over time, I’ve sort of morphed into a version of myself that I’ve been cast as. I think largely it’s because of England, because I’m based here. There’s a lot of period drama and England does it really well – it’s our history.” She’s being modest. In fact, there is something elemental about James that incites such excitable descriptions of her performances as “delightful”, “lovable”, “kind”, “fizzy” and “open-hearted”. She has worked with a dream crop of directors – as well as Branagh, there’s Joe Wright, Danny Boyle, Edgar Wright and Wheatley – and received rave reviews that describe an actor who embodies her characters’ feelings not only with the optimism but also the passion and devastation of their grand literary heritage. Boyle once said of James: “The Americans call it emotionality, and boy has Lily got emotionality. That is where her beauty comes from. People think it is from her physical beauty, but it isn’t, it is actually from her emotional honesty.”

It’s no wonder she finds it hard to let go of the characters she plays – she occupies them, taking parts of them away with her when she leaves. “It’s like, if you read a book again and again at different times in your life, you pick up on different things. They’re so deeply personal, those heroines, but somehow connect to us all in a profound way, where we recognise ourselves in them. I know that if I played all of those characters now, I’d play them differently. But it’s such a gift – as a young actor and a young woman – to be able to explore these characters at different points in my life. I’ve definitely grown through playing them and through inhabiting them.” For James, there is an emotional transaction within each role she plays, bound to her very essence in that moment.

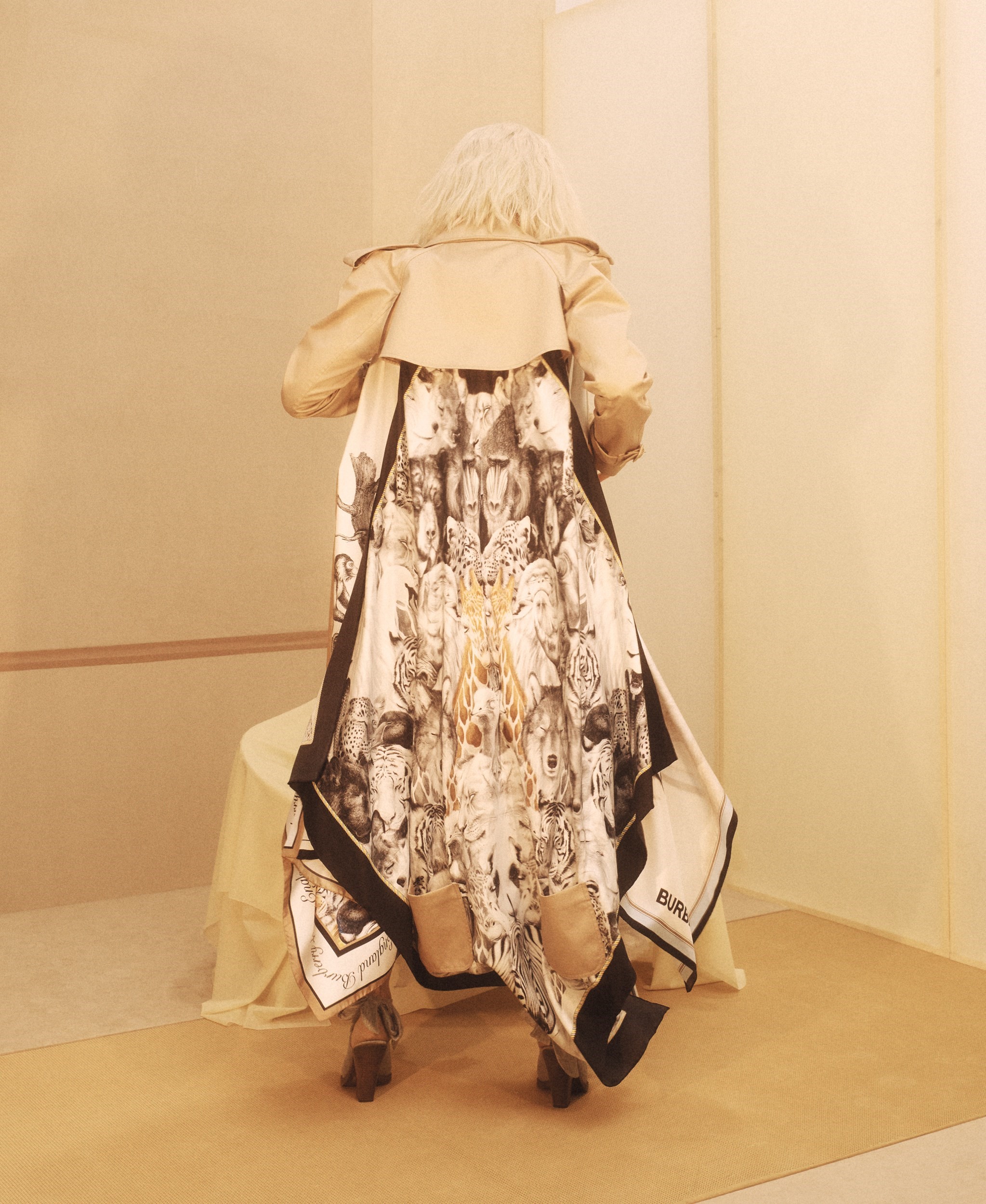

The physical beauty Boyle refers to is not to be underestimated, however. Her face, sculptural and strong, lights up with the flash of a wide, girlish smile. She is able to meld into both the porcelain appearance of a young princess and that of a model for sultry, sensual advertising campaigns. She straddles generational appeal: from the hot star your teenage brother might fancy, to a gloved and beribboned young countess who looks like butter wouldn’t melt. The British heritage brand Burberry saw just this in James – an ambassador for Burberry Beauty’s lines since 2016, she has been a front-row regular at the label’s London ready-to-wear shows ever since, first supporting chief creative officer Christopher Bailey and, since he took the helm in 2018, Riccardo Tisci. She is a quintessentially British actor representing an iconic British brand – her radiant glow and mercurial shades of honeyed blonde blend easily into Tisci’s new age of beige. It certainly can’t hurt the sales of its Matte Glow foundation.

“I do like living in my pain. I don’t mind spiralling because sometimes it helps me feel more ‘me’. At least if you’re connected to your grief or your pain, something feels real. Real and more potent” – Lily James

James is hyper-aware of the inextricable relationship between physical and emotional presence in her profession. “When I’m filming, the first costume fitting is often where I start understanding how the character moves and stands – their internal rhythm,” she says. “I’m definitely a physical, sensual person. I like photo shoots – I love shapes and movement. How I move my body makes me feel something.” Naturally, costume has become a key motif in James’ career – for her more than most – but in the upcoming Rebecca, it is especially pertinent. Rebecca is said to have been Coco Chanel’s favourite book – du Maurier cutting a similarly forward-thinking figure to Chanel at the time it was published – a rumour that sent costume designer Julian Day (Control, Rocketman) searching through the French fashion house’s archives. In the novel, Rebecca’s exquisite clothes, cut for her lithe, handsome figure, are kept, preserved, at the Manderley mansion – each piece an imposing reminder of the elegant shoes the second Mrs de Winter is seemingly expected to fill. Though quite unlike Joan Fontaine’s dowdier portrayal of the character in Hitchcock’s version, James starts out in a steelier look – mannish trousers, blouses – before segueing into one of Mademoiselle Chanel’s signature cardigans with blue edging, a round neck and gilt buttons (one of the words for cardigan in Spain is rebeca, after the first film), as well as a two-piece gold skirt suit for a simmering finale.

“Initially I was worried, thinking, ‘She’s meant to be unfashionable – I can’t wear Chanel.’ But we found a good balance,” says James. “I think I was really annoying because I love that book so much. I clutched to it like a lifeline and wasn’t brave enough for a while to just let it go and say, ‘This is a new version.’ I was like that with War and Peace, too. I’m a bit of a control freak and I don’t trust myself that much, so if there’s something there saying how it should be, I trust that rather than myself, which was a bit difficult. But then I just have to allow myself to really inhabit it.”

When I ask director Edgar Wright about James’ tendency towards self-doubt, he suggests it’s simply another of her tools. “I think if there is any nervousness – I can’t see it – it just comes across as vulnerability, and that in itself is very appealing to any audience,” he writes while in post-production for his new film Last Night in Soho. “I think she is a true movie star. She’s totally believable, relatable and natural, yet she still lights up the screen when she walks into frame.” Day concurs: “She gets so involved in a character – she extracts everything from the script and pulls it through her. She lives and breathes her roles.” In fact, James uses every facet of her nature – her humanity – as a tool for her craft. She remembers wallowing in the toxicity of her miserably ambitious character Eve, in Ivo van Hove’s production of All About Eve (James starred opposite the marvellous Gillian Anderson, accompanied by a PJ Harvey soundtrack, at the Noël Coward Theatre in London last spring). “That was amazing to exist in for a while. Eve’s pretty unpleasant but it was also weirdly pleasant. I’m a bit masochistic in that way. I do like living in my pain. I don’t mind spiralling because sometimes it helps me feel more ‘me’. At least if you’re connected to your grief or your pain, something feels real. Real and more potent.”

James’ masochism extends to dream roles, too: she’s desperate to work with David Fincher. “I love to do things 250 times, until I can’t walk and I’m crying and I’m a broken human being,” she says. But for now, she’s especially keen to collaborate with more female directors – Greta Gerwig and Olivia Wilde rank high on her wish list – and she’s positive about the future for women in film. “There’s now a general initiative to support, foster and nurture female writers and female directors, and inevitably by doing that we’re going to capture women in a different way from through a male lens. There are definitely new voices coming through that are finally being encouraged. So that’s going to change everything and it’s so exciting.”

“If you are always living through your work and characters, at some point you’ve got to connect to who you are, without work defining you” – Lily James

As such, James is currently trying to secure rights to a book she’s just read. She’s holding its title close to her heart – having previously scoured Eimear McBride’s intense A Girl Is a Half-Formed Thing and Jean Rhys’ oeuvre of tortured modernism for adaptable material, she’s settled on this one, “which rocked my world”. The aim is to both produce and star in the film, which would mark her first foray behind the camera. With sights set on Los Angeles as her next home, James seeks a broader offering of roles – “I feel like I’ve probably done too many literary heroines,” she says. But she’s not escaped them yet. This year, she will star in two more 20th-century-set dramas: The Dig, in which she plays Peggy Preston, an archaeologist present at the discovery of the ancient burial site at Sutton Hoo in 1939 (alongside Carey Mulligan and Ralph Fiennes); and The Pursuit of Love – Emily Mortimer’s adaptation of Nancy Mitford’s landmark 1945 novel, for the BBC. James recently celebrated her 30th birthday, chalking up a neat decade since her career began. As an actor who assimilates facets of every role she plays, she’s ready for a new chapter, both on- and off-screen. “If you are always living through your work and characters,” she says, “at some point you’ve got to connect to who you are, without work defining you.”

Hair: Malcolm Edwards at LGA Management. Make-up: Hiromi Ueda at Art and Commerce using Burberry Beauty. Set design: Jabez Bartlett at Streeters. Manicure: Chisato Yamamoto at David Artists using Burberry Beauty. Digital tech: Larry Gorman. Lighting: Matt Moran, Barney Curran and Stefan Ebelewicz. Styling assistants: Molly Shillingford and Ruby Cohen. Seamstress: Carson Darling-Blair at Karen Avenell. Hair assistant: Lewis Stanford. Make-up assistants: Sunao Takahashi and Chloe Holt. Set-design assistants: Ellen Wilson, Harry Stayt and David Konix. Production: Artistry. Post-production: Frederik Heide.

This story originally appeared in AnOther Magazine Spring/Summer 2020, which is on sale internationally from February 13, 2020.