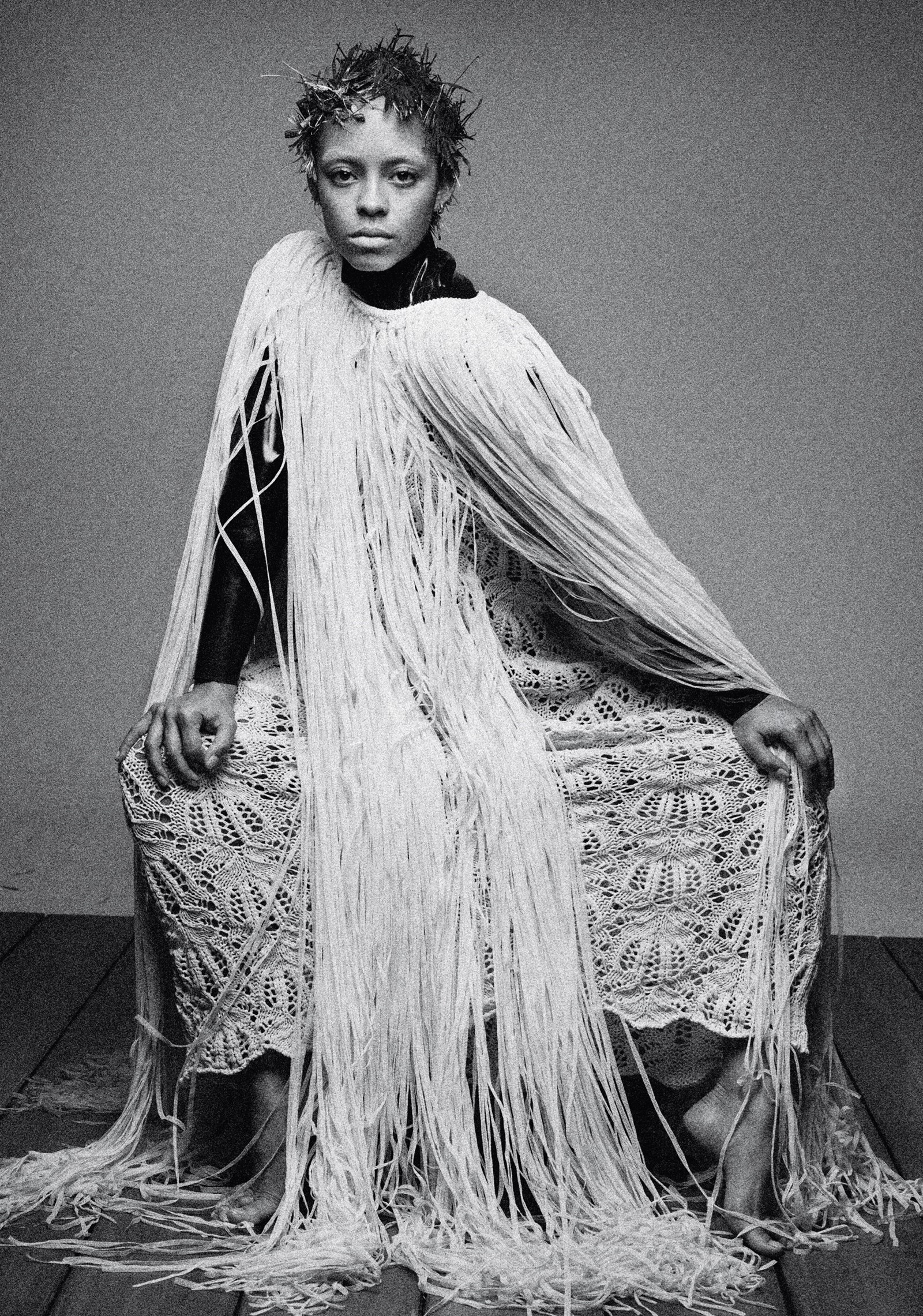

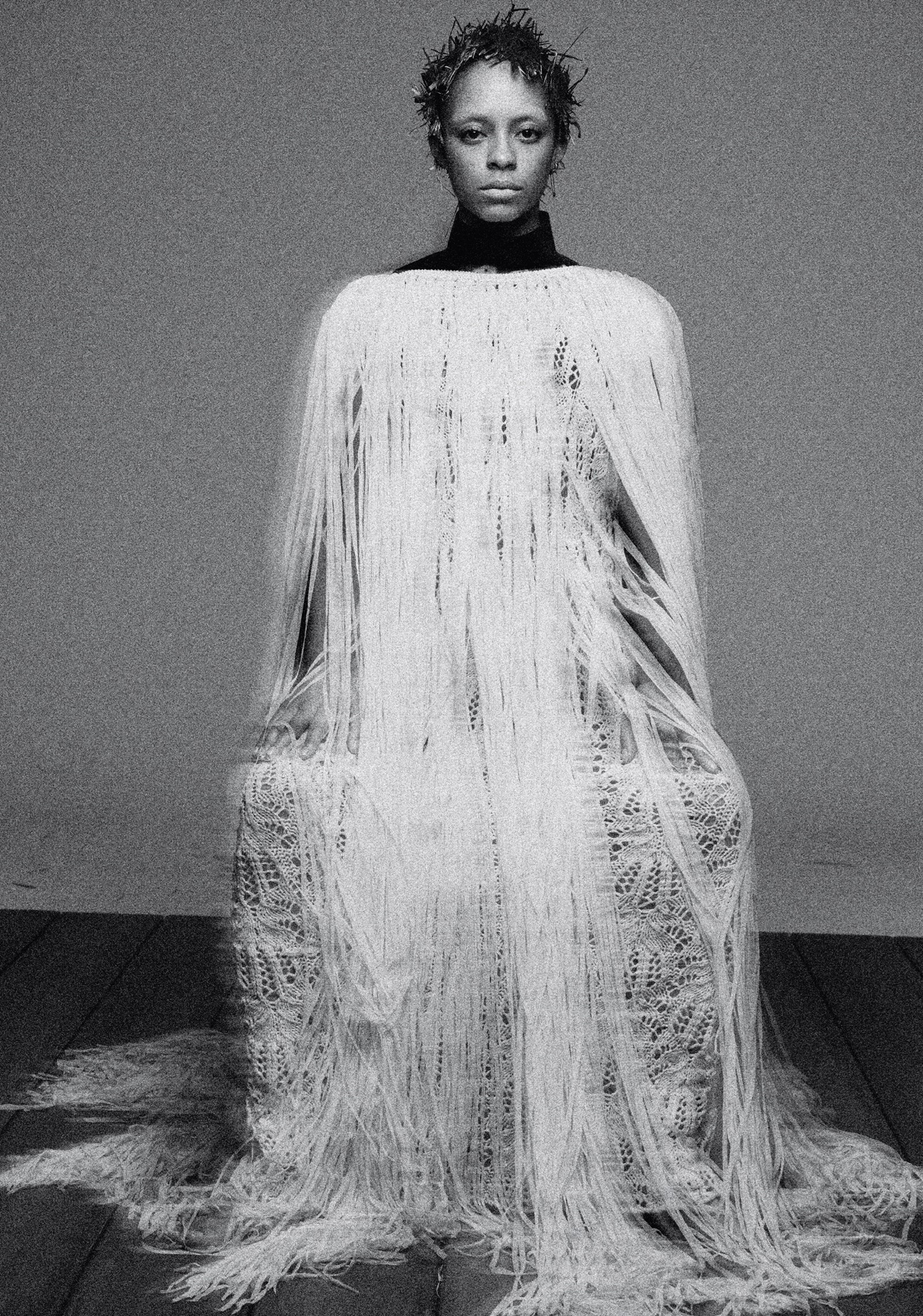

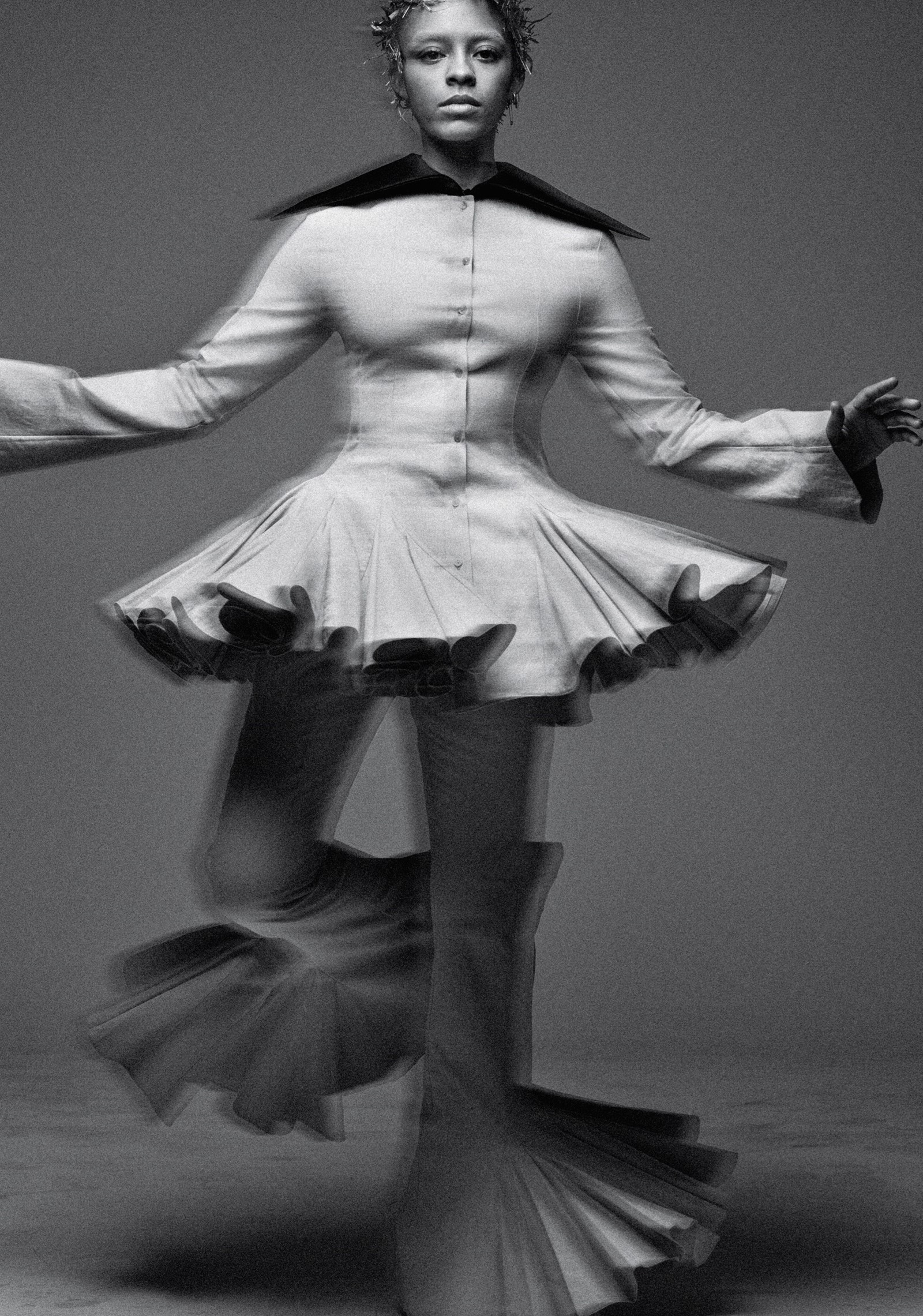

Classical yet modern, grounded yet otherworldly, both Kelsey Lu and the music she creates defy easy categorisation. She is a classically trained cellist and her output today is a unique fusion of everything from jazz to contemporary pop, blues to 1970s folk: her friends call her singular style “Lu-thereal”. She has collaborated with Skrillex, Dev Hynes, Sampha and Solange Knowles, all while forging a career as a determined and uncompromising solo artist. In AnOther Magazine Spring/Summer 2020, we take her powerful physical presence as inspiration for our edit of the season’s most magical looks, while Lu talks about breaking free from her childhood and her determination to live a life of her own.

November 2019. A disused art deco cinema in Hackney, east London, is bathed in a wash of red light. Crowds hush as the musician Kelsey Lu takes the stage for a performance she has called Grounded. Beneath her feet, a pile of dirt. She moves slowly around the microphone stand, her body contorting, her face concealed behind a veil of mesh. She holds out, refusing to sing, the audience suspended in anticipation, uncertain, enthralled. When she finally breaks her silence with the first plaintive note of her improvised opening track, it is nestled between the sounds coming from a suite of live percussionists. The audience is transfixed. They’re fans, of course: fans of a style critics have found difficult to describe, even as they heaped Lu’s debut album, viscerally titled Blood and released in April last year, with plaudits. Naturalistic yet experimental, surreal yet deeply, well, grounded, modern but couched in the bold, resonant sound of classical music by her expert cello playing (she learnt when she was nine) – such myriad descriptors lead NME to, prosaically, dub her music alt-classical. Others, perhaps more enamoured, continue a valiant tussle to better define its fusion of genres and intentions. It’s a sound that, according to The New York Times, her friends call “Lu-thereal”. Which is perhaps the neatest summary, since it is simultaneously utterly singular and entirely otherworldly. That was also the notion behind Grounded: to craft another world, through sound, visuals, costume and movement. This was her coming out. It was an opportunity, maybe her fans’ first, to not simply be an observer of Kelsey Lu, but to dive into her universe.

“It was just a dream come true,” says Lu (as she prefers to be called) of Grounded. We’re talking a week after the Hackney show, seated at a corner table that overlooks the Brooklyn Botanic Garden in New York; Lu sublets a space in nearby Bedford-Stuyvesant and visits often. It is a place of special significance to her. “Nature is so magical to me,” she says as the sun sets over the lush hothouse vegetation. “I knew I wanted there to be dirt on the ground. I wanted the floor to be covered. It represented being at one’s base – that for me is where our roots are. That’s something that everyone can relate to. Even Blood – the name of the record – it all comes from the same reasoning. It’s these things we all spring from that unite us.” Lu wears an earth-toned suit by the Dutch brand Daily Paper and Gucci knuckleduster rings with oversized garnet- and emerald-coloured stones, emphasising her hand movements. Her eyelashes are bright blue with mascara, intensifying her penetrating gaze. “I remember in college studying [Stravinsky’s] The Rite of Spring. When it premiered for the first time, a mob ensued. People hadn’t heard anything like it before. It was really twisted, dissonant, really jarring. I saw Pina Bausch’s interpretation and I got really into her and the way that she incorporated natural elements within her stage design.” Stravinsky and Bausch are both clearly antecedents of and inspirations for Lu’s own approach – ‘Lu-thereal’ encompasses all senses, not just sound. You hardly need her to continue, to tell us that she “wanted to do something similar, to find a way to encapsulate all of my emotions in one performance”. You get it, and her.

Accordingly, Lu was exacting in her preparations for Grounded. Everything, from the location to that veil (a “protective layer” between her and the audience), her costumes (they were multiple and included pieces by a new generation of designers such as Sinéad O’Dwyer, Chopova Lowena and Laura Deanna Fanning, as well as a feathered lion face mask by Sorcha O’Raghallaigh) and that red wash of light (symbolising a presence of power), was meticulously thought through. Even the intervals, more common in theatre or opera, were a chance for the audience to digest what they had just seen. “I think of the work as reflection,” she says. “I also allow the audience to have that reflection themselves – to talk, get a drink, do whatever they need to do. I have found that, in my shows, people are naturally quiet. I feel like, with Grounded, I was finally able to conceptualise the things I’ve been thinking and feeling. I’m finally able to make sense of what I’ve done, what I’m doing, what I want to do.”

Lu is undoubtedly intriguing. Who is she? What is her story? For a few years, I myself wondered. I saw the public and private sides of her. We had been in one another’s orbits for a while, exchanging quick hellos through mutual friends. I saw her from afar at social gatherings, as well as at earlier but equally bewitching performances in both New York and London, where (before Blood) she was opening for another artist. On social media, I saw – and you see – more of her personality on full display. She’s naturally inquisitive, probing, wanting to know more about the origins of questions, my point of view. She turns the tables. She’s funny, too, with a wicked sense of humour that the seriousness of her records may hide. Lu radiates a particular sort of luminescence that only inhabits a special few: those who walk with ease on their path. There is a joy in watching her perform and the way she talks about music makes you inclined to think that to know Lu onstage is to know her offstage, too. She has trouble recalling specific dates and times. Instead, and in her own words, she has lived a life fuelled by “feeling and passion”.

She is also informed by a vivid past, a formative life spent as a Jehovah’s Witness, her teenage years restricted by the demands of a faith imposed on her by her parents and her journey of breaking free. Now, at 30 years old, Lu is assured, having long ago fought through the crippling self-doubt that many her age still experience. She has no reason not to soar. “Some days I wake up after working on something in the studio and I listen to it and it’s like I’m living in an alternative reality, another dimension,” says Lu. “My first feeling is fear but then I think, if it’s something I am not completely comfortable with but it’s what I wanted to try, I should still be doing it. It doesn’t mean it’s not good. I like to consider myself a disruptor, and that disruption starts with me. Who am I to disrupt everyone else if I can’t disrupt myself?”

“I like to consider myself a disruptor, and that disruption starts with me. Who am I to disrupt everyone else if I can’t disrupt myself?” – Kelsey Lu

Our meeting takes place during a rare moment of calm. After months of ping-ponging from a base in Los Angeles, until recently the place she called home, to points all over the globe during the tour for Blood, Lu is getting back to basics. She has spent the morning working on a cover of Neneh Cherry’s Manchild. She toured with her early last year. “I’m actually thinking about scratching the whole thing and starting all over again. It’s like that sometimes,” says Lu. She seems content, particularly to find herself living back in New York, a city she first moved to in 2012. “I moved to LA to make the album and then, over the past year of coming in and out of New York, I felt inspired by it again,” she says. “I missed walking around, I missed interacting with people. [LA is] not the same. It’s really isolated, but that’s what I wanted when I moved there – that feeling of isolation,” she says.

Isolation is a theme that has followed Lu throughout her life – her proximity to it, her need to escape it and, at times, run towards it. She was born and raised in Charlotte, North Carolina, the daughter of a black father and a white mother, both musicians. “He grew up in the segregated part of town, she was rebellious. She grew weed in her room and told her parents it was a Japanese tomato plant!” They met at college when Lu’s mother, a pianist, would go and see her father play drums in his band Fungus Blues, and both became Jehovah’s Witnesses, “after someone knocked on his door”, says Lu. “He started studying [the movement], then my mom started studying to prove him wrong and then she realised it was the ‘truth’. They became Witnesses together. They had my sister Jessica, then they had me.” Her activity, outside her faith, was music. “It’s the only other thing that I knew.” Her parents listened to music, introducing their children to Nina Simone, Ella Fitzgerald, Fela Kuti, Tito Puente, Thelonius Monk, Stanley Clarke and Jimi Hendrix, and Lu learnt to play the piano, the violin and then the cello. “All of my friends were in the [Jehovah’s Witness] community, so that was my whole world. I didn’t know any kids from school, and music was the only thing my parents were hugely supportive of,” she says. “I was in all the youth orchestras, the community orchestras, all the competitions. It was my only time spent with other people. One day, my sister, mother and I went to see the Charlotte Symphony Orchestra [perform]. When we came out, we heard music and realised it was our high-school prom happening in another room [in the theatre]! We hadn’t even known it was happening. They were playing Britney Spears – we snuck in for two songs and then left.”

Put simply, her teenage years were contentious for her conservative parents. Though her love of music endured, so did her desire to do the things that teenagers do. “It was the only time I could sneak away to smoke and be with my friends. One day, I left orchestra early and came back to the house with sunglasses on to cover up the fact I was high. My mum knew exactly what was up and was so mad. When I went up to my room, I sprayed perfume in my own eyes so I would cry. I was getting ready for the Oscars, you know? She was angry but really she was trying to protect my dad. They were so scared of it leading to something else. For my dad, drugs were associated with a lot of bad things – [he’d been in prison] because of selling drugs, many of his friends were dying around him because of drugs. Him turning to religion was a way of saving his own life. Jehovah was a figure that saved him from death – it was very serious.”

For her part, Lu had dreams of being a “cello-playing hippie” and studying at Appalachian State University (ASU) in Boone, North Carolina, as encouraged by her school teacher. “We would go there for orchestra competitions and it’s steeped in nature. I love the mountains,” she says. One evening, she left early from her high-school job at Hollister – she was only allowed to do it because it was at a mall where her father had a booth that he would sell his paintings from – to attend a house party, her first ever. At the same time, her mother intercepted her university acceptance letter. An argument escalated to violence and led to 18-year-old Lu jumping out of the window, into her car, and off to see her sister at the University of North Carolina School of the Arts in Winston-Salem. She abandoned her plans to attend ASU, choosing instead to study alongside her sister and reap the benefits of a much-needed familial connection. Nothing if not audacious, she waited outside the cello teacher’s door for a chance to show him she was worthy of a place on the programme. “I said, ‘Hi, I got to go here. I have to. I don’t have any other choice.’ He was like, ‘Let me hear you play.’ And [after] I played for him, he was like, ‘OK, I’m going to try everything I can to get you in at the end of the year.’” A lot of scholarship money had already been allocated by that point, but he raised as much money as he could for her, which she supplemented with student loans. “And that was my out,” she says.

Lu enjoyed the freedom afforded her by both her life at university and her music, but loathed the theory classes and the rigidity of the course. “Music, for me, was always a feeling. I wanted to experience everything connected to it – to take dance classes and learn about Pina Bausch, to take acting classes. So, to all of a sudden be in this, ‘No, you’re here to study this one thing, so this is what you’re going to do,’ was stifling to me. It was never about what was written on a page.”

She left the course after a year, stayed in Winston-Salem and began waitressing. One night at a bar she had been taken to by a colleague, she met an underground rap crew known as United Minds Conglomerate, who had a studio in the city. They found out Lu was a cellist. “I would just play over their beats. It didn’t last very long.” After a show and her first tab of ecstasy, she sang. She had loved all the greats growing up – in particular Fitzgerald and Simone – but until then had used her vocals more as a form of catharsis than anything else, singing to herself in her room. Her bandmates were blown away. She was then introduced to rap quartet Nappy Roots, who first invited Lu to play on their new album in Atlanta, and then to go on tour with them. “I was the only girl on tour, living out of a suitcase and, when we weren’t on the road, I was staying with my aunt and uncle who live close to Athens, in Georgia. My aunt’s a beekeeper and my uncle is a contractor, and they live on a lot of land in the middle of the woods. So I’d kind of go down and write a lot of songs out there. I earned $50 a show, or something, but I was happy,” she says.

“Music, for me, was always a feeling. I wanted to experience everything connected to it” – Kelsey Lu

When a new love called her to New York, she waitressed and did odd jobs that made her money. But then a Levi’s casting that called – like kismet – for an “ethnic female cellist” came her way, and she finally earned enough to concentrate on her music. “It was union protected, so it paid properly. I had started making songs on my phone, on GarageBand. [With the money] I got a computer, a boot pedal and rented a studio in Bushwick. I would go to my studio and just get lost in the room,” she says. She experimented with her voice in a meaningful way, pairing it with the more bluesy music she wrote on her guitar.

By then, Lu had a steady flow of modelling work, which provided her with enough income to fully experiment with and hone her sound. “I met [the musician] Kyp Malone at a point when the relationship I had moved to New York for became abusive – both emotionally and sexually. Kyp became a safe zone for me.” He suggested they work on music together. They went to a cabin on the river near Hudson, in upstate New York, for more than a week and wrote, staying up all night – by the end, they had almost a whole album’s worth of electropop music, so far unpublished. “I was experimenting and writing, doing the odd show, when I met Dean Bein from True Panther Records. He asked me what the plan was.” Lu hadn’t thought past the New York gigs she was doing, though the work she had made upstate often crossed her mind. “When I was playing in the studio, I couldn’t capture the music in a way that felt right – I knew it would be so amazing live. I had been playing in an interactive theatre performance piece at this church in Greenpoint and knew the sound of the space, inside and out. It felt really comfortable.” From it came her EP Church, her debut release, in 2016. The gravity of her life experience became her own personal communion, in a space where she had so often felt compromised. The reviews were rave and felt like a homecoming after what had been years of struggle.

She signed to Columbia Records in 2017 and began working on Blood (“Their A&R saw me at one of my shows and I thought, ‘If I’m going to infiltrate the system like I want to, I’m going to be with a major label’”). To tackle that task of defining the indefinable, Lu’s music is a paradoxically harmonious collection of disparate inspirations. With Blood, released three years after Church, she has noticeably evolved: the listener is taken through her classical upbringing, her love of jazz greats, bluesy California 1970s folk and, at times, contemporary pop. It’s autobiographical. One track, Foreign Car, is a sensual story of lust wrapped in a cheeky metaphor: “Pedal to the metal, make you work / And we’re risin’ / The horizon’s approachin’ us, and … / I, I, I, I, I, I, I wanna drive you hard.” Due West – an unlikely Skrillex collaboration and ode to her then-West Coast home – is positioned with unexpected comfort alongside her remake of 10cc’s I’m Not in Love. The album concludes in the operatic feeling of the title track. That song’s lyrics – “Jazz ain’t dead, it’s in us all / History has taught us hope / Hope is the answer / Yes, it is” – are a perfect example of Lu’s constant meditation on what might be, rather than what is. No reference is linear; none is supposed to be. Deeply spiritual, emotive, powerful and disarming. To listen to Lu’s music is to go along with an artist in the very midst of their journey – she is inviting you along for the ride.

Her appeal crosses disciplines: her music is featured in HBO’s Euphoria; she’s celebrated in fashion circles for her flamboyant personal style, her use of clothing a further form of communication. Take the video for her 2018 single Shades of Blue, in which Lu wears oversized skater tees in one scene, a virulent tangerine tulle Molly Goddard gown in the next. She has sat front row at Gucci, performed for Jil Sander in Milan and Tokyo, and modelled in Kenzo and Nike campaigns, the brands likely inspired by her Instagram feed, which shows the full spectrum of her sartorial choices. Feathers, masks, gowns, everyday regalia with a rainbow of hair and eyebrow colours to match. For Lu, fashion offers complete freedom of expression. And despite an uncompromising and idiosyncratic approach to her physicality, performance and music, she is now tapping into a sensibility that makes her appealing to the many rather than the insider few.

“I think this stage in my life is presenting me with a new outlook on where I want to take my music next... Now more than ever, I have this determination to go further” – Kelsey Lu

Lu recently released a remix album, Blood Transfusion, has been talking to house legend Omar-S, who features on another collaboration, about future projects and wants to work on a country album next. In a world of back-to-back releases, she finds herself in the company of collaborators (and friends) such as Dev Hynes, Sampha and Florence Welch, all celebrated for their return to craft and traditional musicality in an almost entirely digital age. She also sees acting in her future – though only when she finds the right role, she stresses. “I just turned something down. It was like a version of Insecure, which I would watch but I don’t want to be in.” She curls her lip. “Psychological movies, things that get into your psyche are interesting to me. For that film for Shades of Blue, we filmed for five days – I went 200 per cent on the physicality, [to see] how far I can push my body.” In the nine-minute short, Lu dances for almost its entirety, across every terrain – by the sheer drops of cliffs, through forests and at the edges of remote expanses of water.

She recently parted ways with Columbia, looking forward to the future as an independent artist. “I think this stage in my life is presenting me with a new outlook on where I want to take my music next. It’s now important to ask myself, ‘Do I want to be on a label? If I were, how would it serve me?’ I think, for me, the dream is my own label, but I see this as reclaiming the freedom I had prior [to being with Columbia]. Like with the Grounded show. I can experiment again, do EPs, do things how I want to because I have that freedom back. Now more than ever, I have this determination to go further.”

Days after we sit down, I receive a DM on Instagram from Lu with a photo of a tarot card. She explains to me she drew it at random. It was the tree card, specifically concerned with extending deep into where you find comfort. And it read:

When you feel disconnected from your body, you are inevitably disconnected from Earth.

So get yourself grounded. You can do so quite simply.

And with it was a message from Lu: “I thought it was too perfect not to share.”

Hair: Duffy at Streeters. Make-up: Mark Carrasquillo at Streeters Using Tom Ford Beauty. Set Design: Piers Hanmer at Art and Commerce. Manicure: Lolly Koon at the Wall Group Using Le Vernis in Ballerina by Chanel and Gel Lab Pro Colour in Brand New Day by Deborah Lippmann. Digital Tech: Nicholas Ong. Lighting: Nick Brinley, Nicholas Krasznai and Alex Hopkins. Styling Assistants: Molly Shillingford, Devanté Rollins, Salma Arif, Ruby Cohen, Rosie Mulder and Ben Springham. Tailor: Taylor Spong. Hair Assistants: Lukas Tralmer and Dale Delaporte. Make-up Assistant: Ryo Kuramoto. Set-design Coordinator: Morgan Zvanut. Set-design Assistants: Louis Sarowsky and Jerry Mraz. Post-production: Gloss Studio.

This story originally appeared in AnOther Magazine Spring/Summer 2020, which is on sale internationally from February 13, 2020.

Blood Transfusion EP is out now.