When the masterful Belgian designer Dries Van Noten wanted to evoke an exuberance he felt the times were lacking, he decided to call on the former couturier Christian Lacroix, whose creations redefined taste for almost a quarter of a century. The unprecedented, unimaginable collaboration was the story of the Spring/Summer 2020 season – a demonstration of generosity, creative freedom, sublime confidence and joy. Over the course of autumn 2019, AnOther Magazine was granted unique access to document the secret preparations for this one-off, once-in-a-lifetime show. And, in a season devoted to a luxurious excess synonymous with Lacroix haute couture in its heyday, this collection is the real deal – a reworking of the past for the present, a true melding of two creative souls that makes the heart soar.

It’s a blue-skied early-autumn morning and the elegant warehouse building where Dries Van Noten houses his highly distinctive fashion business and which overlooks the old port of Antwerp is filled with diffused sunlight. Van Noten moved his company headquarters here in 2000; during the 1950s, precious works of art were stored within its sturdy walls. By the turn of the millennium, the neighbourhood was a wilderness “full of crumbling buildings”, Van Noten told me when I visited for the first time, in 2011, “old and neglected”. Since his arrival the district has become a fashionable marina, complete with quayside museum, thriving cafes, restaurants and more. Honestly, he preferred it when it was more rundown. Van Noten is interested in patina, in a sense of time passing – and times past – despite an unswerving commitment to modernity. From the top floor, where he has his studio, the views over his home town, including the medieval cathedral with its famous Rubens altarpieces, are spectacular. Inside, proof that Van Noten is an avid collector with broad if impeccable taste is apparent: here are oak cabinets, tables and desks dating back to the 1930s, snapped up when the Antwerp Law Courts put them on the market, there is a black 1960s high-shine sofa and oil-painted portraits of King Baudouin and Queen Fabiola of Belgium in ornate, gilded frames. The mood is effortlessly coherent despite the disparity of the contents, reflective of a distinctly northern-European sense of pride in one’s environment, domesticity and even homeliness on one level – not least because Van Noten has a loyal team, many of whom have been with him for years – and expressive of impassioned creativity, design, manufacture and an eclectic sensibility that is well known on another. Along with the designer’s sprawling mansion in the countryside, which is an hour out of town and shared with his long-time partner in fashion and in life Patrick Vangheluwe, where both men tend to its famous rose garden, this is Van Noten’s world.

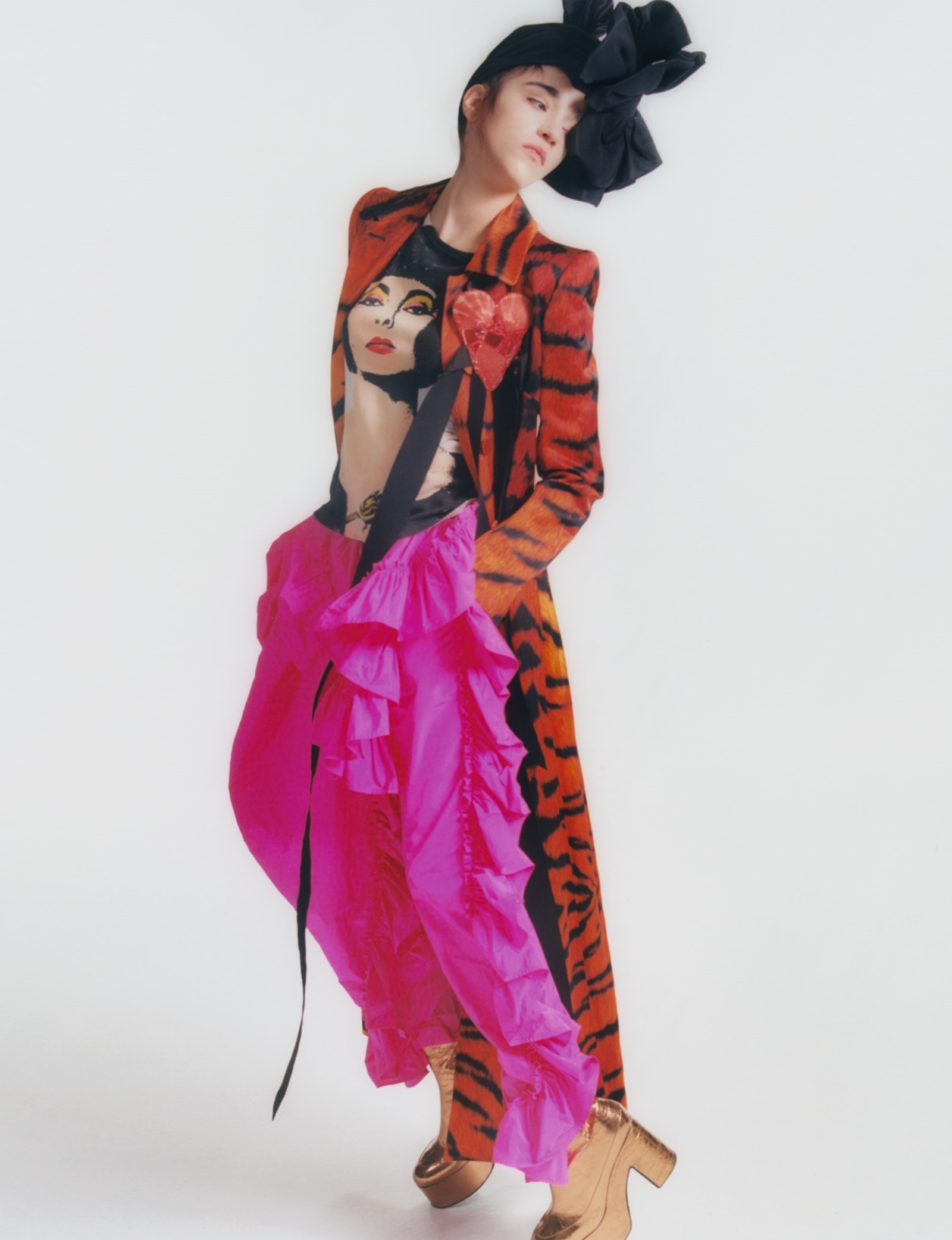

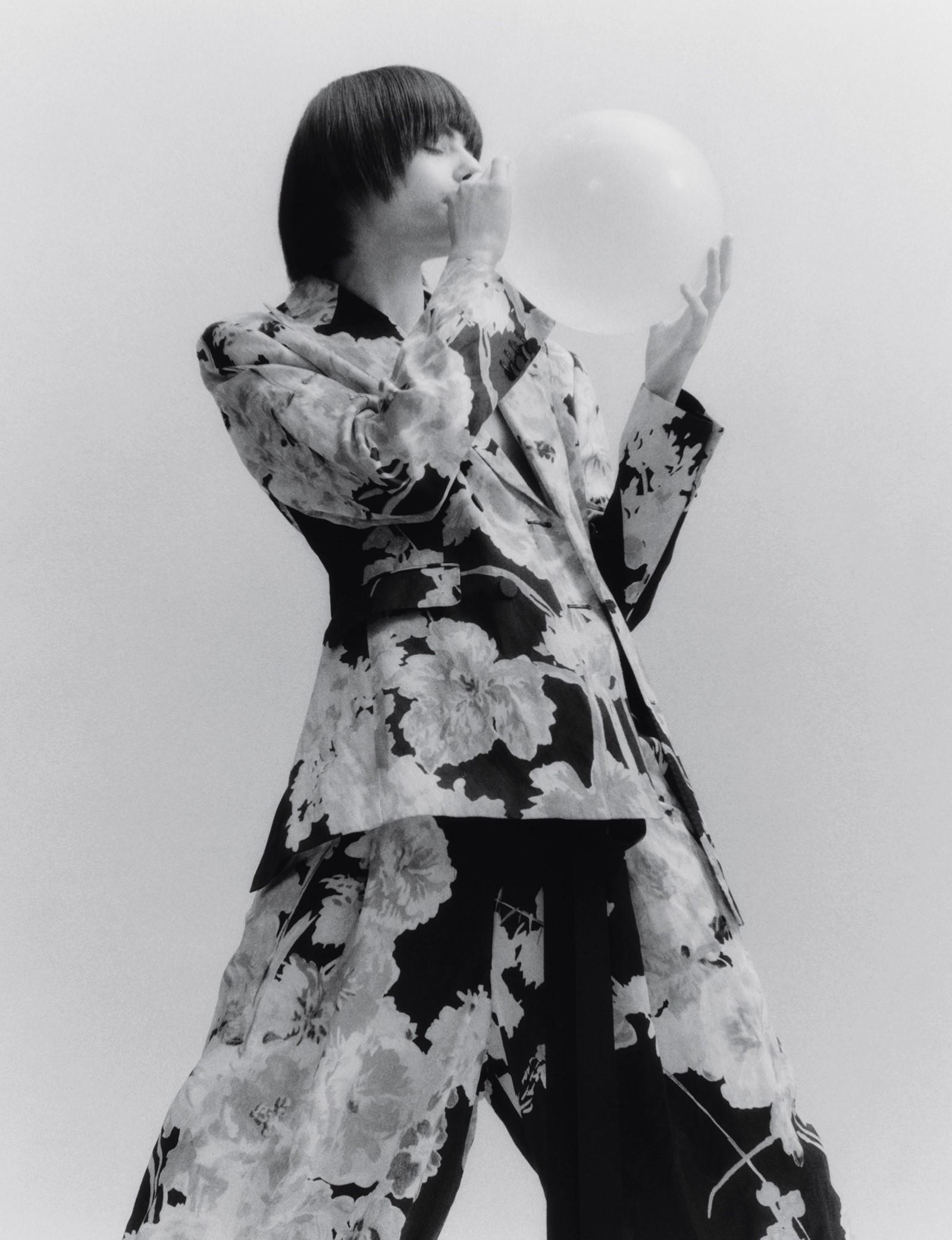

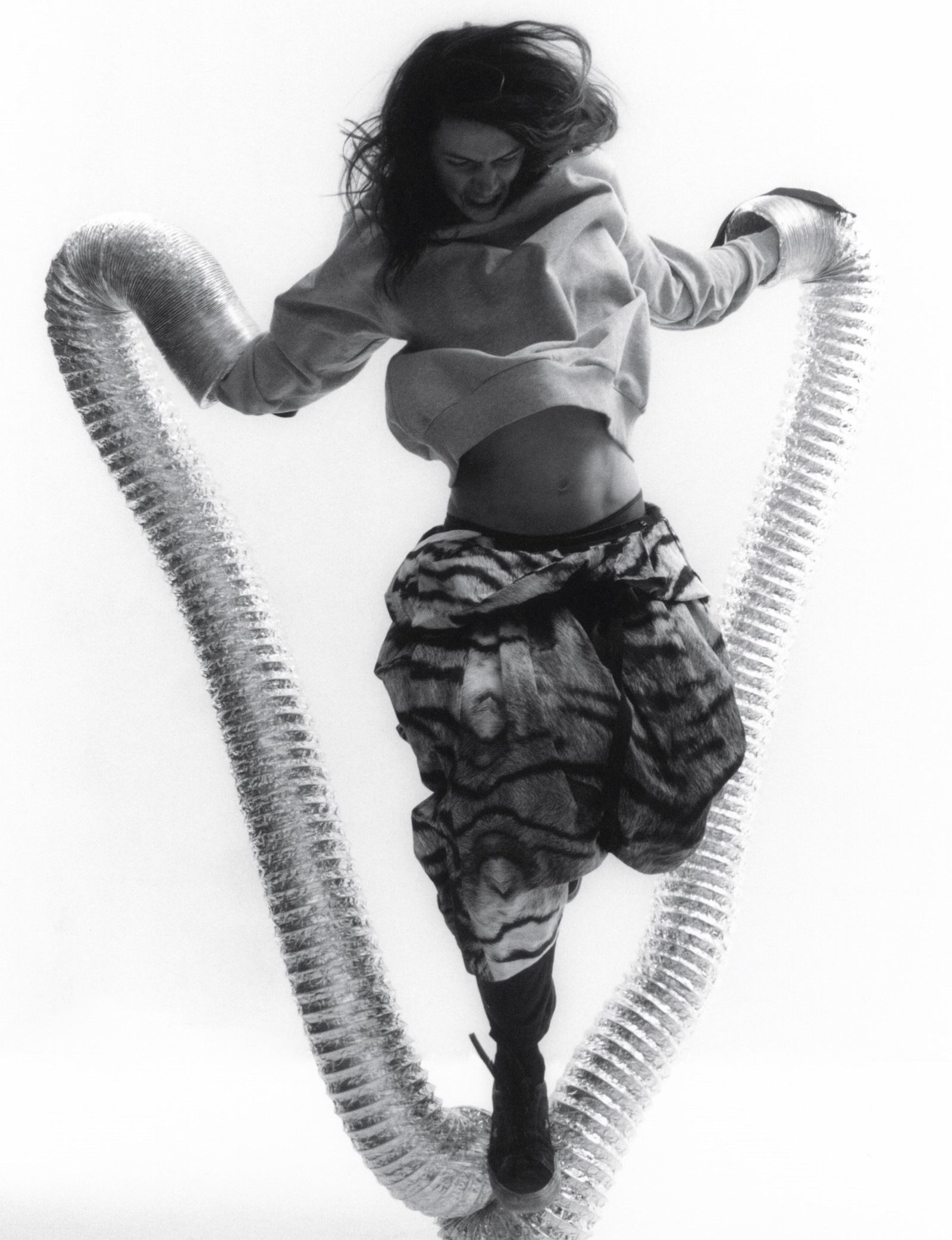

The collection that Dries Van Noten will show in Paris in a little over two weeks’ time sings on rails all around. It boasts more exuberant florals than might be expected, even from this most green-fingered designer. They are huge – roses, of course, in colours bolder and brighter than nature ever intended, as well as garlands of more exotic blooms, printed, embroidered and over-embroidered in fine silk and metal threads, then jewelled. There are flamenco frills, polka dots, a predominance of scarlet, fuchsia, tiger stripes and leopard spots – maximalism, no holds barred. In retrospect, the provenance of the garments in question has been labelled this season’s “best-kept secret” but, for the purposes of our meeting, Van Noten explains: “At the start, when I began looking for inspiration, I was constantly drawn to the 1980s and 90s, to a love of dressing up, to couture, to beauty, to audacity – to joy,” he says. “And I realised that I was most insistently drawn to the work – to the universe – of Christian Lacroix. So I thought why not just phone him, why not phone Christian and ask whether he would enjoy working with me on a collection? He immediately said yes.”

Such a meeting of minds was never intended, Van Noten is quick to affirm now, as an homage. Lacroix is among fashion’s most referenced designers: it is almost as if, because he himself no longer shows, it’s fair game to plunder his archive. As an aside, that’s debatable – as Lacroix later puts it: “In the end, I’m still here.” But for Van Noten, “it’s not an homage, it’s not that. It is a collection for now and I really wanted to make a perfect blend of our two worlds. Christian was much more than a living mood board. He was really there. Because of course this collection is a little out of our comfort zone. It’s an evolution of what we normally do. We joked sometimes, sitting around a table, and when Christian wasn’t there, we’d say, ‘Christian, talk to us, how would you do it?’”

“I admire Dries and was sometimes jealous of him because he has a kind of modernity. I was very excited when I was invited to work with him on this collection and am very happy now to be closer to him, to have seen how he works” – Christian Lacroix

Today, Christian is here, working with Van Noten on the finishing touches to the collection in question. And, bang on cue, he enters the space, dressed in beige linen chinos and shirt – Van Noten is similarly attired in black and navy. “I feel like a tourist,” Lacroix says – this experience has brought him back into the heart of fashion for the first time in a decade. Coffee and biscuits are served – delicious coffee in delicate cups, delicious biscuits, perfectly oval; Van Noten is an immaculate host. We three sit down to talk. To be in the presence of either man is quite something. To listen to them tell their stories in sync, discuss their viewpoints on fashion and the world beyond, looking back over two long and grand creative careers that span more than three decades, is, even from the perspective of the more seasoned fashion follower, nothing short of awe-inspiring. Above all, in a world where any self-deprecation is likely as faux as the fur on most contemporary runways, their heartfelt respect for one another’s talents and ability to suspend their egos in an environment hardly famous for that is remarkable.

With that in mind: “I’m not here to tell my story,” says Lacroix. “I admire Dries and was sometimes jealous of him because he has a kind of modernity. I was very excited when I was invited to work with him on this collection and am very happy now to be closer to him, to have seen how he works. I am not an admirer of many people but I am a customer, I wear Dries a lot. I don’t want to be back in fashion but I always thought that Dries’ company was different from the others, because of the freedom, because of the distinctions. Very, very often I noticed that we have the same colours, the same love of print, of mixing, so it was interesting ... ”

Van Noten’s company has indeed always been run on different terms from others. Until 2018, when the designer sold a majority stake to the family-run Spanish fragrance and fashion conglomerate Puig, which also owns Nina Ricci, Carolina Herrera, Paco Rabanne and Jean Paul Gaultier, it was completely independent. Dries Van Noten doesn’t advertise – he doesn’t need to, customers queue around the block at his Antwerp store every time a new collection drops – and there are no pre-collections, just two women’s and men’s collections, albeit huge ones, each year. Sales are driven by ready-to-wear as opposed to accessories or perfume – though he has those, too. Long term, the designer will continue as chief creative officer and chairman, owning a significant minority stake in the business he founded. He told Women’s Wear Daily at the time news of the deal broke: “I have been searching for a strong partner for the company which I have built for more than 30 years. I am especially happy that Antwerp and my team will remain at the company’s heart and centre. Our relationship with our customers is a cherished one and it will only benefit from this enhanced vision.” And now: “I am still an independent soul,” he says, “not completely independent any more, but my soul and vision are still free, and Christian has really made me feel that. Everything today is so branded, so focused, so edited that it was nice for me to see whether one designer could work with another on a collection. It’s so different to how people look at a house now, to a name, and for me that wasn’t important this time. What was important was the opportunity to work with Christian. And wow, that has been fantastic.”

Lacroix has visited and worked with Van Noten on this collection on a regular basis since the project was conceived. When they first began fittings, it was, says Van Noten, “like the game you play as children where you all draw one part. I put two pieces together and Christian would be, ‘Hmmm,’ and he would add maybe a piece of embroidery, a feather, something like that.” The project is, both men insist, a one-off. “It happened in a very spontaneous, natural way and we appreciated each other’s creativity,” says Van Noten. “It’s not that it was like, ‘It’s my name on it, you can suggest, but I do.’ No, it was a very open thing. And for me, knowing that Christian was there, the fact that we could have the help of Christian to make this collection, was so inspiring for us.”

“I am still an independent soul, not completely independent any more, but my soul and vision are still free, and Christian has really made me feel that” – Dries Van Noten

“Each time we have met he has amazed me,” Lacroix chimes in. “As a Latin I am fascinated by creativity in the north. I don’t know Belgium very well but there is an elegance that is restrained but discreetly generous. Dries has that. I also love him because I always failed at the ready-to-wear. I didn’t know how to find the balance between theatre and couture, perhaps because people were always expecting something beyond. I don’t remember whether it was Baudelaire, but a poet once said the real artist, the real designer, the real painter, was the one who knows when to stop. I never knew when to stop.” He’s laughing. “I am jealous of Dries because he succeeded in that, and because what he does still often looks like couture.”

This season, more than ever, that is certainly the case.

But: “In every collection you have to find a balance. I’m not designing haute couture, it’s prêt-à-porter, so you have to consider that,” Van Noten says. “OK, you can dream and make only dresses with thousands of metres of fabric and ribbon – we did a few of those. Then Christian comes in and says, ‘Why don’t you add a drawstring in the back because the back is now a little flat compared to the front, so ... ’ Things like that happened quite often. Ultimately, though, the collection has to reflect reality, people have to be able to wear it today, in the street. That was possibly the most challenging part, not to lose myself in the fun but not to forget the fun. That to me was very important, it was important to bring that back.”

Among fashion’s most potent forces is its ability to make people dream, to inject optimism, fantasy and wit into their lives. Very few have ever understood that power as profoundly as Christian Lacroix, who emerged on the scene in the 1980s and whose name immediately became synonymous with excess, with dressing to impress, with gaiety and abandon. “It’s Lacroix, sweetie,” as they say in Ab Fab heaven. We all know the story. Lacroix’s work was nothing if not a welcome antidote to the power-driven, strong-shouldered, Amazonian looks that dominated that decade. And women loved him for that, for allowing them to be women, ultra-feminine dreamers, dressed in extravagant and whimsical designs. This was fashion folly at its most elevated – a sight for sore eyes.

Today the designer, who is 68, works under the moniker XCLX. Lacroix used an ‘X’ as his signature as a teenager and has now revived it because he no longer owns the commercial rights to his name. He sold it back in 1987, when Bernard Arnault, then president of Financière Agache, parent company of both Christian Dior and Boussac, initially invested $8 million to open his haute couture house. Lacroix was then on the crest of a wave: in the six years prior, the designer had single-handedly reversed the fortunes of the dusty French couture house of Jean Patou, giving the moneyed customer blithe puffball skirts, ruffled petticoats, jewel-coloured minks and saying, as reported by Georgina Howell in The Sunday Times Magazine following his signature debut: “Everyone had forgotten Patou, so I had to shout for attention.” And that he did, to rapturous response. He was credited with revitalising interest in couture as an art form, selling clothes to young aristocrats and celebrities and lowering the average age of the couture clientele by a decade. At Lacroix’s own shows, legend has it, fashion editors sobbed and even passed out, such was the impact of it all (we’re fragile souls, easily moved, perhaps). In print, superlatives flowed in a way they hadn’t since, in 1958, the morning after Yves Saint Laurent’s haute couture debut for Dior (neatly enough), when Le Figaro declared: “Saint Laurent has saved France.” The 1987 counterpart? “For Lacroix a triumph; for couture, a future,” as trumpeted in The New York Times following Lacroix’s first own-label show.

“I don’t remember whether it was Baudelaire, but a poet once said the real artist, the real designer, the real painter, was the one who knows when to stop. I never knew when to stop. I am jealous of Dries because he succeeded in that, and because what he does still often looks like couture” – Christian Lacroix

That future proved short-lived. Fewer than 25 years after that most auspicious of beginnings – in July 2009 – Lacroix stepped down, the most high-profile fashion casualty of the 2007-2008 financial crisis. In 2005, his house and the name behind it had become the property of Falic Fashion Group; four years later, they placed it into administration. Over 22 years, the house of Lacroix never turned a profit: the designer is the first to admit that he struggled to translate the fantasy and grandeur of his collections into a financially viable reality. There was ready-to-wear, there was a second line, Bazar, and a perfume named C’est la vie!, which came in a bottle with a stopper shaped like a coral branch (pink). None of it worked, although the couture runway it sprang from continued to mesmerise right until the bitter end. A Christian Lacroix haute couture show was a thing of exquisite beauty – anachronistic beauty, perhaps, from the brides with their towering mantillas to the overblown flounces of duchesse satin and even the single carnations, scarlet, magenta or orange maybe, placed on seats. Those in attendance would hurl these at their fashion hero as he came out to take his bows, like a matador feted in the ring. His final couture show, executed in straitened circumstances from deadstock fabric and sewn by petites mains who stitched for love, not money, was as magnificent as Lacroix’s extravagant debut and, as with that first show, it ended with a standing ovation. Christian Lacroix’s haute couture house, on the Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, opposite the Bristol hotel, was then shuttered. Its former salons now sell high-end luggage, quite possibly to the guests of that hotel who used to buy his clothes, and to their sons and daughters.

M Lacroix recently started an Instagram feed, tagged @fkachristianlacroix, as in ‘formerly known as’. He is, by his own account, amazed by the number of young people who are following him, people neither lucky – nor, in many instances, old – enough to have witnessed the aforementioned presentations first-hand. Lacroix’s output, during his career often divisive, seems now universally loved – revered. In person, the man is as warm, open, funny and flamboyant as his work might suggest: here is a designer who has indeed brought happiness and, yes, joy to every socialite worth her haute couture credentials, just as he does still to students and young designers looking for a vision of fashion in its purest form – for hyper fashion, if you will. If Lacroix’s move away from the industry is mourned by the many, let’s not forget that designing costume for theatre was always his first love, and today he enjoys the luxury of focusing on that.

“Christian does amazing things for theatre,” says Van Noten, who has also designed for the stage – notably for the New York City Ballet in 2016. “I have always followed that. The theatre creates the possibility of a more open way of dreaming, it allows you to dream and to look back, gives you much more freedom. That’s what I think went wrong for fashion for me, it’s such a strange time – maybe freedom is what we were looking for again. Can we do this? No, we cannot. We hesitated. The world is so grim and fashion became so flat that you start to question yourself. And knowing that Christian was there and the fact that we could have the help of Christian to make this was so inspiring for us. OK, do we have big colours? OK, let’s have big colours. Maybe a little more bright, OK more bright.”

“I always thought that we are all actors of our lives and, like the theatre, we have our presidents and prime ministers who are actors – or clowns – it’s a show,” Lacroix says. “And we have to be dressed for this show. I never made any distinction between a costume for an opera singer, a dancer or a couture customer. It’s one dress for one occasion, one of a kind, for Phaedra or for A Midsummer Night’s Dream.”

“I don’t want to be seen as an ostrich putting his head in the sand. You can see this collection more perhaps as a remedy for a grim world than as a hiding place. I’m too much of a realist for that. I wanted to do something full of skills, full of materials, full of emotion” – Dries Van Noten

If that sounds rarefied, that was never the point. Lacroix doesn’t live in a gilded cage, though his head, it is probably fair to say, is in the clouds. “I sketch and I decorate everyday life,” is how he puts it. “I just try to do something which might make people happier. Even when I was doing couture, I was also doing TGV trains.” He revamped their carriages in 2005 – purple and scarlet for second class; more chartreuse than might be expected in such a milieu in first. In 2012, he designed the livery for the new Citadis trams in Montpellier and, given that city’s proximity to the Mediterranean, drew on an aquatic theme. “I’m happy to work on everything connected to life,” he confirms, “on buses, trains, trams, but with a touch that is not just grey steel. The trams in Montpellier were decorated with the sea, with fish, so when at 6am you have to go to work, perhaps it would uplift you a bit.”

Back in the moment – and in fashion – and here’s how the collaboration to end all collaborations (or the “fantastical bromance”, as Vogue Runway put it quite brilliantly) began. In March 2019, Dries Van Noten and Christian Lacroix sat down for a first meeting on the Champs-Elysées in Paris. The location for their rendezvous was halfway between Antwerp and Arles, where, in 1951, the latter was born and raised. Van Noten took with him fabric swatches, reference imagery, embroidery samples. In Lacroix’s opinion: “It was all done, he didn’t need me.” Van Noten begged to differ. The creative surge and sheer joy of working alongside this fashion deity was worth fighting for. And so followed a meeting of minds, an expression of dual intention and respect, a romance for sure between two designers and, in turn, between both of them and fashion. And Van Noten is right. In a world where corporate politics – and just politics – appear more complex and pressurised than ever, more grey, in fact, and creativity is often compromised by commerce, not always to the best effect, such an openly idealistic mindset is welcome: the licence to indulge in pure expression through clothing is, increasingly, rare.

Of course, fashion is vitally tied to the moment in which it is created. The timing of the launch of Lacroix’s own haute couture house remains significant. In October 1987, a week after Black Monday, he presented his debut, first unveiled in Paris three months earlier, in the winter garden of the World Financial Centre in New York; it was swiftly labelled “Crash Chic”. It seemed a bizarre setting in which to promote poufs, bustles, Spanish frills, extravagant embroideries, acres of jewel-coloured duchesse satin and miles of grosgrain. Despite that, women adored it – because of that, women adored it.

It is impossible not to see parallels in the fact that the windows of the building that houses Puig, where Lacroix and Van Noten began their talks last spring, more than 30 years on, had fallen prey to a crash of a rather different kind: they had been smashed only hours earlier by the gilets jaunes who continued to wreak havoc over the months that followed and still do. Now especially, Van Noten argues, is the time to uphold fashion’s spirit-lifting qualities, to be bold, brave, extreme. “I don’t want to be seen as an ostrich putting his head in the sand,” he argues. “You can see this collection more perhaps as a remedy for a grim world than as a hiding place. I’m too much of a realist for that. I wanted to do something full of skills, full of materials, full of emotion.”

***

From the very start of his career, Dries Van Noten, now 61 (both men are Taurean), has enriched the lives of both women and men with his expansive imagination and artful eye, evoking a sense of the celebration of humanity through his early experimental and inspirational shows – guests lounging on bolsters and mattresses, sipping mint tea, or eating from bowls piled high with fruit as models walked – and increasingly sophisticated clothes. He graduated from the fashion school of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp in 1981, started his business in 1986 and his first fashion show (men’s) took place in 1991, for the Spring/Summer 1992 season. Van Noten’s work, too, was initially a riposte to the Montanas, Armanis and Muglers that dominated the 1980s when he emerged; it was gentler, more considerate of the body within the clothes. As part of the Antwerp Six – the others were Walter Van Beirendonck, Marina Yee, Ann Demeulemeester, Dirk Van Saene and Dirk Bikkembergs – Van Noten, like Lacroix, positioned himself very much against the mainstream, going against the flow: determined, uncompromising.

“I was aware of the Antwerp Six, of course,” Lacroix remembers. The designer also attended Van Noten’s 50th show (women’s Spring/Summer 2005), staged on a huge banqueting table – following a huge banquet – in a disused factory (in La Courneuve) on the outskirts of Paris. “You very kindly invited me for the weekend,” Lacroix says to Van Noten. “So we met – I was very shy. You are quite shy. So we couldn’t, at such a party, talk about fashion. But it was amazing.” And so it was: 500 guests watching the world’s most celebrated models make their way down a tabletop 140 feet long in clothing inspired by Eastern European folklore – full skirts in black and ecru stripes, rich gold bullion embroideries, and crystal embellishment that echoed the 130 chandeliers lighting the clothes. Ethnic jacquards were woven in silk on age-old looms in Como. To undercut an often-decorative aesthetic, many looks were worn with oversized white cotton shirts, grounding it all, as is Van Noten’s wont.

“I was totally afraid of life, of the present. Escapism was everything – now and then” – Christian Lacroix

Lacroix’s fashion is clearly more explicit a foil to the dour things in life than Van Noten’s. As a child growing up in Provence, “I was totally afraid of life, of the present. Escapism was everything – now and then,” he says. And so he lost himself, watching his mother and her friends transforming old petticoats found in attics into the latest styles as seen in Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar (“I loved seeing them standing on the table to do the hemline, but I was not cutting. I was not interested at all”) and in endlessly sketching women (“pin-ups”) in dresses. He found magic, too, in antique etchings and photographs, in the films of Luchino Visconti (later he says it was his original ambition to be the Italian director’s assistant), in the bright colours of the Arlésienne and bullfighting (“Where I grew up, we played at being gladiators and bullfighters, not cowboys”) and in the grandeur of antiquity, so present in that part of the world. “It wasn’t that I wanted to meet Napoleon or Cleopatra,” he says. “But I wanted to be able to hear their accents, to ask them what they were eating, doing, watch their gestures, everyday things. I love Alice in Wonderland, when she goes through the mirror, and as a child, one of my favourite things was to look at an old picture until I fell inside it. The past – I was obsessed by the history of costume. The first money I ever had was spent at the flea market, aged eight. Old pictures, old magazines, everything. I still have them.”

Van Noten is equally sensitive to his environment – to that highly particular mix of Dutch Protestant austerity and Burgundian opulence that makes the country where he was born and lives to this day so uniquely layered. Like his garden, his clothes combine colour and shape, texture and proportion, with exuberant and unexpected eclecticism, opulence, humour and warmth. His background, however, is very different, steeped in the culture of Antwerp and the very real tradition of sourcing, manufacturing and retailing clothes. His grandfather was a tourneur, an expert at taking apart, cleaning, then remaking second-hand clothes to sell on, who later opened a store specialising in men’s clothing. By the 1950s, he had a factory dedicated to fabric production and, with ready-to-wear still in its nascency, sold off-the-peg tailoring alongside made-to-measure designs. Van Noten’s father joined the business at the height of its prosperity, starting his own, Nutson, an upscale boutique in Essen, selling womenswear, menswear and childrenswear and drawing on the American concept of shopping as lifestyle – entertainment – ahead of his time. A second store, Van Noten Couture, opened its doors in the city centre not long after, stocking Ungaro, Ferragamo and Zegna, among others, and there young Dries was more than happy to help out. It was his mother who took care of the home, meanwhile, displaying just the extreme attention to her environment, as her son soon would, too. “My mother loved lace and embroideries,” Van Noten once told me. “On special occasions she always dressed the table beautifully, each time putting on different linen and placing lace in the middle of it.” Between the ages of 6 and 16, Van Noten was taught by Jesuit priests intent on turning bright young boys into doctors and such like, but he was more enamoured by joining his parents on buying trips in Europe during the long summers. “I was 12 years old, immersed in my parents’ store,” he says. Small wonder he ended up studying fashion not law, say, and obsessing over Bowie and the dawn of the punk movement while continuing to work for his father and design clothes for various companies on a freelance basis. “I never did it just for the money, though,” he says. “I did it because I loved it.”

How important is fashion?

DVN: Fashion is important.

CL: For me I never knew if fashion was a way to be like your neighbour or a way of being yourself, expressing yourself as different from your neighbour.

DVN: I think people who want to look like their neighbours use fashion like that and people who want to use fashion to stand out use fashion to stand out. It can go both ways and, in the end, you have people who want to stand out and shine, glimmer or be very sober – it’s not always with excess that you stand out. When anyone who gets up in the morning stands in front of a mirror and takes out a shirt, a pair of trousers or whatever, it’s an act of fashion. Either you want to blend in, or you want to stand out. Fashion is a fake system. At the time of Poiret, no one was thinking about fashion. They wanted beautiful clothes, they wanted to dream, that type of thing. Of course that was a different world from now.

CL: But when you say fashion is for a girl who wants to stand out or who wants to be like her neighbour, I was able to provide the stuff to be different but I never succeeded in providing a way to be in the mood, on trend. My fashion was always elsewhere.

***

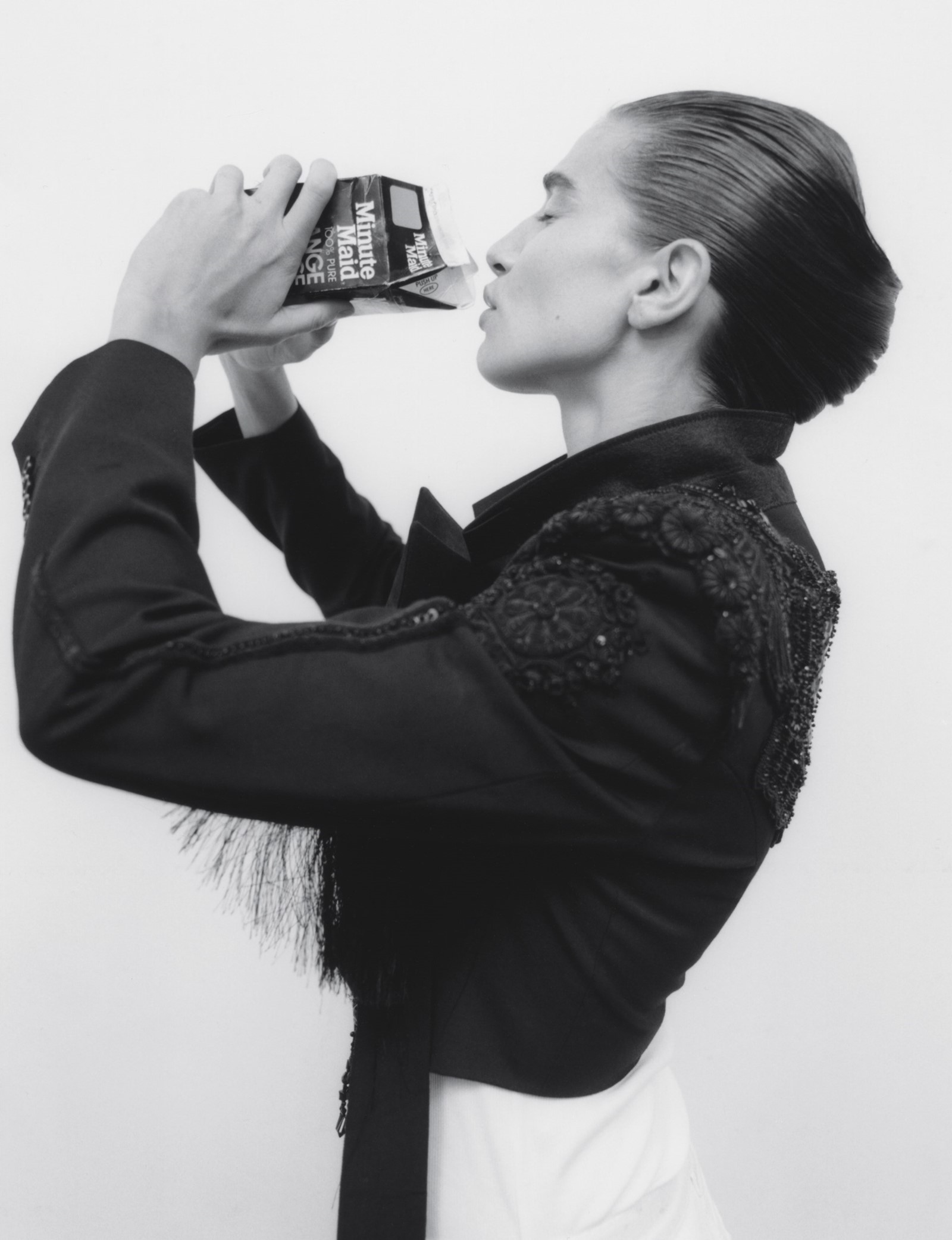

Following a splendid three-course lunch served outside on the terrace in the sunshine, Van Noten and Lacroix go back to the job in hand. Lacroix approaches a cerulean blue duster coat, pulls it off the rails and exclaims, “I could eat it.” He is almost dancing. Elsewhere, all his signatures are in place, filtered through Van Noten’s celebrated, cerebral and sensitive sensibility: waltzing polka dots, broad stripes, ruffles, matador jackets, gigot sleeves, silks woven with the aforementioned flowers, pouf skirts, duchesse satins – embroidered, printed and flouncing from neck- and waistlines, collars and cuffs.

Van Noten explains that the acid floral jacquards are, in fact, more muted than the 18th- and early-19th-century designs that inspired them. The fading of the precious originals is deceptive, but before age dimmed their intense colouration, they were anything but shy; the purple, for example, the designer says, has been taken down a little under his watchful eye, subduing the violence of its effect. “I was also thinking of Lady Honoria Lyndon [Marisa Berenson’s character in Kubrick’s masterpiece Barry Lyndon] for the collection,” he says. “Normally, we would have maybe one or two Lyon jacquards in a collection. This time we have more special pieces than ever before.” The garments in question were woven on looms that stretch back to the period in which that film was set and clearly reference Berenson’s spectacular wardrobe. “I think couture is relevant in the way that it feeds fashion, keeps tradition and skills alive,” the designer continues. “It’s theoretical fashion, pure creativity, far away from reality, and that’s a good thing. I considered using pattern cutters from Paris because this collection is more couture than anything I have done before, but Christian said, ‘Your pattern cutters are fantastic.’ So we used our own team. Up until now we have created a stage which is really quite believable, where the audience can connect and see themselves and think, OK, this is how I want to be next season. That’s what we try to obtain – is it believable? So, for one season now, we go to a dream, not to something believable. And how do we balance that? Are we not even in couture now but in theatre? Is this too much, too over the top? Is it fashionable? I hope we achieved the right balance between ready-to-wear and couture.”

“So, for one season now, we go to a dream, not to something believable. And how do we balance that? Are we not even in couture now but in theatre? Is this too much, too over the top? Is it fashionable? I hope we achieved the right balance between ready-to-wear and couture” – Dries Van Noten

Balance is a key notion. With that in mind, the vocabulary of Dries Van Noten is fused immaculately with that of Christian Lacroix: said jacquards have been scanned and appear as prints across cotton and organza; lightweight polyesters, made out of recycled plastic bottles and coated papers rustle alongside precious French silks; billowing trains grace nothing more haute than a parka, albeit gold. Basic white singlets are decorated with a single overblown embroidered sleeve here, jeans with an appliquéd feather or feather print on one leg there. If Lacroix was among the most feted couturiers of the latter part of the 20th century, known and revered for the extravagance of his designs, Van Noten sublimates daywear and is, above all, a ready-to-wear designer, justifiably acclaimed as one of the world’s most masterful. In the end, then, theirs is a heavenly match and, with that, the received notion that the fashion designer is driven by vanity and as such unlikely ever to want to share the spotlight, is blown out of the water.

“For me the most challenging moment was arriving with the team, a team who were used to working together,” says Lacroix. “I was like an alien, arriving like a new baby in the family with my southern Catholic bad taste in a very elegant, northern-European company. I was afraid of that because I didn’t know them. Wondering, ‘What do they think?’ At the very beginning I didn’t dare to be myself. I was very, very shy, I didn’t say one word. Step by step, though, I saw we had the same process, and I became part of that team. I was not expecting something so familiar as a way of being, or a way of working. I was also reassured by their choices, by the French silks, which might have been my own choice, and the idea of the ribbon – printed onto basics from sweat- and T-shirts to jeans – was genius and something I never got. I love that this was not just capturing me in details, it’s the spirit of what I did.”

In the end, that is not so very surprising. The work of both Van Noten and Lacroix is indebted to culture, drawing upon fine art in particular. Before starting out as a couturier, Lacroix studied history of art at the École du Louvre and the Sorbonne from 1973 to 1977 – but, in his words, “unsuccessfully”. Van Noten has created collections inspired by Dalí, Bacon and Rothko, among others, and is as comfortable drawing on high culture as he is referencing contemporary music or film, or all three at the same time. Both men love collage, tensions, apparent contrasts – disparate references combined in a single look or even a garment. They favour colour, in apparently jarring but somehow harmonious juxtapositions, and are masters of mixing print to the point where, in lesser hands, it might disturb the eye, consistently walking that fine line between good and bad taste.

When is something too much, and when is it not enough?

DVN: When it’s too evident, that’s not enough. For me ‘too much’ is not something I arrive at quickly. I prefer to add more and more layers, which afterwards you can dissect, peel away, like an onion. If you’re working with a jacquard, OK, you can still have an embroidery, you can still put some rings on it, some jewels, maybe a little feather here or there. That is something Christian is a master of. And perhaps in our trying to be very contemporary and modern and fashionable, we lost sight of that a little. And now, with the help of Christian, I am very happy to find that again and to be pushed even more – not excessively, because excess may be negative, but enough to find the right dose.

CL: Excess is easy. When I was young, my motto was too much is never enough. Mixing and matching is what Dries knows how to do. I truly admire the way he mixes and matches fabric and print. Even if you have four different prints on one girl, once she arrives, it’s coherent, it’s not disturbing, it’s a kind of alchemy. I remember once the philosopher François Dagognet came to one of my shows and he said, “Your coherence is coming from your incoherence.” I was so proud.

DVN: For me there has to be contrast, a tension, all those things that, at first glimpse, are intriguing but you don’t know if they’re nice or ugly. Is the balance between beauty and ugliness right? Something purely beautiful is boring for me. And that is something really central, especially in this collection. Christian clearly loves women, you feel that. You want to give women the tools to enjoy, to be beautiful, to sparkle.

“I love Dries’ clothes,” says Lacroix, “but also, and without knowing him, you can read a lot into the ambience that surrounds them, into the set, into everything around the collection. It’s part of his mind, it’s part of his sensibility and what he’s trying to bring to people.” From the moment he first showed on the runway, everything from the location to the soundtrack has been part of a richly coherent narrative for Van Noten.

The location moves to Paris at the end of September, and the powers that be at Dries Van Noten’s office in that city, giving nothing much away, go so far as to communicate that Dries Van Noten’s forthcoming womenswear collection is likely to be a special one. Demonstrating that it’s perhaps best not to give up one’s day job and to leave detection, well, to detectives, the fashion rumour mill goes into overdrive, suggesting the designer may be about to retire. Those who had ever received a note from Lacroix would have perceived something rather different when the Dries Van Noten show invitation, written in the former’s flamboyant hand, arrived. The location is the Opéra Bastille because, Van Noten says, the opera is home to Christian’s work today.” (Ever playful, Lacroix is quick to point out that his office is just down the road – also advantageous.) “It was important that this was the habitat of Christian,” Van Noten explains. “On the other hand, it’s a space that nobody knows and it’s concrete, not a traditional opera. I love the fact that people think they’re going to the opera but in fact it’s more of a bunker. Also, to show such an opulent collection we needed a place that was very spare – pared down.”

As guests filed into the venue they found a single red rose – Van Noten’s favourite flower but a reference to the Lacroix carnation, of course – placed on each seat, marked with a label reading simply DVN x CLX. The secret is well and truly out and the atmosphere of elation that fills this monolithic auditorium is genuinely heart-warming, as befits the magnanimous gesture, not to mention magnificent work of the brains behind it. From the first look out – a black canvas jacket cut to a vaguely 18th-century line paired with white jeans printed, yes, with a huge black feather – to the sweetest of all brides, in a white singlet and jeans again but surrounded by a fluttering veil, this time of real feathers, and a jewel-encrusted cloche sprouting two more, the show is a triumph. Dries Van Noten and Christian Lacroix step out to take their bows on either side of her, holding her hands, and notwithstanding the fact that the majority of the audience has been on the road for a month now, it erupts. Van Noten is famously a reserved character, but he is smiling – broadly.

When asked what he would like people to take from this collection, he says: “Everybody can take something different. I think there is the fun of looking at and wearing beautiful things, of course. It’s really a step back from fashion as a business and very liberating in that way. Also Christian is such a fun person. He’s never very serious. So you sit and you look at a silhouette and you say, ‘OK, walk, walk again. Hmmm, hmmm. Should we put a feather, maybe we should put a feather?’ There’s humour but nothing is ever ridiculous, it’s just on the edge. It’s a discussion. Can you do a full skirt with 50 metres of polka-dot ruffles on the skirt? Er, yes. Why not? Moiré. Woven jacquard, perhaps with tiger stripes, leopard spots. OK, let’s have big shapes, let’s have big colours, big prints. A little bigger, a little brighter? Why not? Why not?”

The Loch Lomond- and Glasgow-Based Post-Punk Band Walt Disco Comprises James Potter on Vocals, Dave Morgan on Keys, Finlay Mccarthy on Bass, Jack Martin on Drums and Lewis Carmichael on Guitar. Anna Acquroff Is the Enigmatic Lead Vocalist of Five-Person Scottish Band Medicine Cabinet, Which Also Comprises Eilidh O’Brien and Joshua Cakir on Guitar, Cahal Menzies on Bass and Thomas Lawrence on Drums. Part Band, Part Artist Collective, the Group’s Theatrical Live Sets Tell Enchanting Stories.

Hair: Ryan Mitchell at Streeters using Bumble and Bumble. Make-up: Hiromi Ueda at Art and Commerce using Desert Dream and Le Lift by Chanel. Models: Anahi Puntin at Select Models, Florence at Tess Management, Kieran at Tomorrow Is Another Day, Lola Nicon at Rebel Management, Sihana Shalaj at IMG and Zso at Premium Models. Talent: Anna from Medicine Cabinet, Dave, James, Jack and Finlay from Walt Disco. Casting: Jess Hallett at Streeters. Set design: Jabez Bartlett at Streeters. Manicure: Adam Slee at Streeters using Le Vernis in Rouge Noir and La Crème Main by Chanel. Digital tech: John Heyes. Photographic assistants: Darren Gwynn and Ivano Pagnussat. Styling assistants: Lydia Simpson, Angus Mcevoy and Meja Taserud. Seamstress: Tina Kalivas. Hair assistants: Mike Mahoney and Akua Gyamfi. Make-up assistants: Chloe Holt and Sunao Takahashi. Set-design assistants: Ellen Wilson, Louis Simenon and Alister Osbourne. Production: Holmes Production

This story originally appeared in AnOther Magazine Spring/Summer 2020, which is on sale internationally now.