She whispers the emphasis: “It’s so far from my life, you know?” Julianne Moore’s life at the moment seems like a pretty good place to be. She has her gang about her at home in the West Village; a dopey black Labrador lollops over and falls asleep under the coffee table, and her daughter kneels down on the rug next to him to draw pictures. “It’s funny,” she says. “Time spent with children and dogs ... they want to be near you, with you. It’s great.” Funny too, that she should be so associated with the opposite of all this, with what she once called “ordinary, almost domestic tragedies”, all those women, storms raging inside, unravelling exquisitely on screen. And it is family life – so far, as she says, from her own – pitched at the deathscream of Greek tragedy that unfolds in her new film, Savage Grace.

Julianne Moore is youthful, girlish even, if the word can be used to describe a smart and engaged woman in her 40s. She talks politics and liberal positions on intervention, in Iraq and Darfur (by way of David Hare’s thorny play, The Vertical Hour, in which she made her Broadway debut last year). She sizes up the climate of the independent film industry in America right now – “gambling” is how she describes investors backing small projects with their fingers crossed behind their backs for box office returns. And she talks about the spirited commitment of the handful of South and Central American directors who are working internationally (she is about to start filming with The Constant Gardener and City of God director Fernando Meirelles). Moore’s life, it would seem, is informed by her belief in communities, the families we make at work, in our homes, and our responsibility to the world around us. “I think it’s the ideal way for people to live,” she calls out from the hallway. It’s why she lives in New York, where her neighbours know her kids’ names. It explains too, perhaps, the arc of a career that has brought her back to work with particular writers and directors again and again – the late Robert Altman, Todd Haynes, Paul Thomas Anderson. And yet, she can be childlike too, giggling with her daughter, or goofing around with her husband, the director Bart Freundlich.

Responsibility, or the absence of it, Moore says as she settles on the sofa after locating some crayons from a drawer, is at the heart of the tragedy in Savage Grace. The film, which is directed by Tom Kalin, tells the true story of the American socialite Barbara Baekeland, who in 1972 was murdered in London by her 26-year-old son, with a kitchen knife to the chest. The Baekelands, Barbara, her husband Brooks and their son Tony, were fabulous, if no longer fabulously wealthy (the thousands of Chanel suits Barbara was famous for were copies knocked out by a clever dressmaker). They were dubbed the Buchanans by one acquaintance after Daisy and Tom in Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, and fluttering between the playgrounds of the privileged amid a walkon cast that included Tennessee Williams, Duchamp, Warhol and Diana Vreeland. The Baekeland murder being a New York story, and New York being her city, Moore has friends in literary circles who remembered the award-winning book published about the case in the mid-80s, on which the film is based. Others remembered siren beauty Barbara herself. It was Moore’s friend Christine Vachon – whose company Killer Films also produces Todd Haynes’s films – who sent her the script. “She was probably two or three months old,” Moore says looking over at her daughter. “We were on vacation and I was sitting in bed. I can still see her, lying next to me, this tiny little bundle. I was reading this script, and thinking, ‘Wow.’ It’s horrifying, absolutely horrifying, but at the same time fascinating.”

“Independent film is not quite independent anymore. When it started, there was this idea that you were investing very little because you weren’t expecting huge returns” – Julianne Moore

The Baekelands lived the clichés of the beautiful and the damned. The couple forced their young son to read from the Marquis de Sade at dinner parties to improve his stutter. Barbara attempted suicide four times, and Brooks ran off with the only girlfriend Tony ever brought home. The real horror, in the end though, was incest. Barbara, who was often wildly inappropriate, slept with Tony in an apparent attempt to cure him of being gay. Later, he murdered her, as many in their clique had predicted. “You’re dealing with people with so much money and so little responsibility, it’s interesting,” says Moore. “Everybody said, ‘Oh we knew he’d kill her.’ And did anyone do anything? They just watched it happen.”

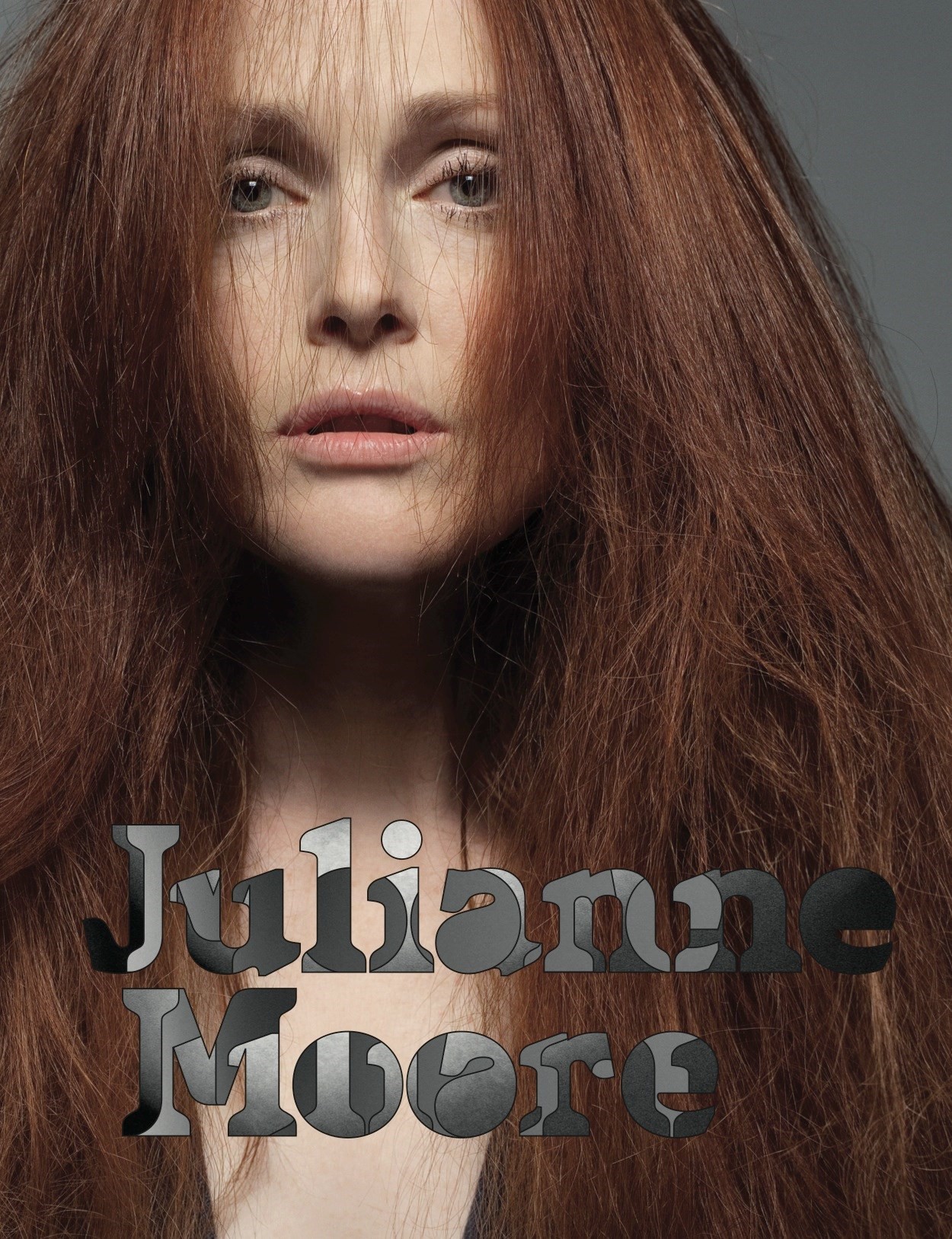

This most certainly is not the stuff of a feel-good indie film with its eyes on the box office prize. “Independent film is not quite independent anymore,” is Moore’s assessment of the industry’s new ambitions. “When it started, there was this idea that you were investing very little because you weren’t expecting huge returns. You were just trying to make your money back, and do the kind of movies that you wanted to.” Her daughter starts school next year, which goes to show the years that it has taken to pull together funding for Savage Grace. In the meantime, word of mouth attaching her to the story has brought her to the attention of some of the tragedy’s players. There was the woman who accompanied Tony from Broadmoor back to New York (friends had campaigned for his release), where he would kill again. “She came up to me at a cocktail party, saying, ‘I feel so terrible, I didn’t know.’” A strange apology, directed at who, Julianne Moore or Barbara Baekeland? “I know.” The apology makes perfect sense when you see pictures of Barbara, with her “bonfire of red hair” and “milkmaid skin” – Natalie Robins and Steven ML Aronson’s description in their book Savage Grace. One woman, whose daughter was in pre-school with Moore’s son and who had known Barbara as a child, came up to her to say how much she looked like the woman she was about to play. “And I do, I really do!”

Barbara Baekeland’s social ambition is a world away from Julianne Moore an hour ago, pounding the streets near her home in regulation blue jeans and Converse. She waves a “Hi!” to a guy across the street (“he runs the garage up there”), and stops briefly to catch up with some mothers drinking coffee outside a cafe. (Their kids, her daughter included, are meant to be at a pool party nearby, but rain has kept them away.) Moore is, she says, an urban person, and New York is a good city for her. “Bart grew up here, and I moved here right after college. It’s real community living. What did I read recently?...” she breaks off. “That’s nice honey, what’s that?” She met her husband, on the set of his first film, and she’s appeared in two more. She continues, “It was an article about children and families, saying that people were meant to live in groups of 12. So, you should try to live life as much as if you were in a group of 12. You have those people to rely on, those people to be with, to think about and to care for you.”

“I saw Three Women in college. I thought, ‘Who is that guy?’ I hadn’t seen Nashville, I hadn’t seen [Robert Altman’s] movies ... And I thought, this is what I want to do, I want to do that kind of acting” – Julianne Moore

Moore’s own childhood was less settled, her father was in the army and the family was often on the move. She moved to New York in 1983, waitressing and working in theatre before landing the part of twins on a daytime soap. Back then, she had the “Lucky Way”– a system of magical thinking – a daily ritual in which she would leave the house at the exact same time every day, adjusting her strides as she walked to make the crossings on green lights. Success would ensure a lucky performance or a good day at work, while presumably there are plenty enough setbacks for an actor to throw at fate on days the Lucky Way failed. Back then, in her 20s, it was tough, but no worse for her than anyone else, she says and struggling is, after all, what your 20s are meant to be about. “Really, if you think about it, in any profession, how do you get from A to Z, how do you do that? It seems impossible. But if you’re interested in something and you pursue it, before you realise it, you’re doing it for a living. Certainly it’s true with acting. It’s absurd.”

It was perhaps a trick of destiny – very magical thinking – that it was Robert Altman who gave Moore her first significant film role. The director spotted her in a New York production of Uncle Vanya and gave her a role in Short Cuts. For her part, Moore pinpoints watching an Altman movie as a defining moment. “I saw Three Women in college. I thought, ‘Who is that guy?’ I hadn’t seen Nashville, I hadn’t seen his movies. I went to high school in Germany and only saw whatever was on at the local movie theatre. And I thought, this is what I want to do, I want to do that kind of acting.” In Short Cuts, she plays the artist who, on the face of it, is so thoroughly modern that she is postpain, post-love, post-feeling. It’s left to a Pierrot clown’s tear painted on her face at the close of a drunken barbecue to show us what’s going on inside. Moore went on to work with Altman on Cookie’s Fortune, and spoke at the memorial service after his death last year. “I started by saying that I didn’t think any of us thought Bob would ever die. From when I first knew Bob, he was always sick.” She remembers her first day on the set of Short Cuts, standing next to his director’s chair in front of the monitor, when all of a sudden, Altman stands up, to go out to the bathroom, and crew and cast hear him being sick. Moore is laughing as she tells the story. “He comes back in, and sits on his chair, ‘Action!’ That is the kind of guy he is...” she momentarily loses her tense. “He was well and happy when he was working, and that was what kept him going. He always got better.”

It’s impossible to type Moore’s performances. Domestic tragedies, maybe. Very loosely, you could say that she often plays women on the edge, in crisis, on the verge, but that’s inadequate. And the obvious exception is her naked artist in The Big Lebowski. Perhaps it’s so difficult because you never feel she is “doing a Julianne Moore” – there’s no tic, or knack she relies on, no shorthand to get us there. In Paul Thomas Anderson’s Magnolia, self-medicated and over-medicated, she rails at a pharmacist’s assistant “shutthefuckup, shutthefuckup, shutthefuckup”. It’s funny, but it’s more than that. After all, what could be more sad than a woman who falls in love with her husband, the man she married for his money, when he is dying. “I was cursing Paul,” she jokes. “He’d just pitched her so high, I had to find a way to understand her, so that it wouldn’t be sheer comedy.” And then there is poor Amber Waves in Boogie Nights, the porn star who so badly wants to be a mother to her son, but can’t make the changes that might make it happen. It is Amber, loving and lovely as she is, who gives Mark Wahlberg’s Dirk Diggler coke for the first time. “What I love about that, what I feel about most of us is that we are responsible for our tragedies,” says Moore. “That’s the way it is in life, it’s not always clear.”

“If you think about it, in any profession, how do you get from A to Z, how do you do that? It seems impossible. But if you’re interested in something and you pursue it, before you realise it, you’re doing it for a living” – Julianne Moore

Perhaps her most extraordinary performance to date is The Hours, in which she barely speaks at all, a personality in the white-out of depression, all that pain expressed in the way Laura Brown moves on screen, or fixes a smile just a little too long. “David (Hare, who wrote the screenplay) teased me. He was always saying, ‘Do you want some more lines?’ And I was like, ‘No, no.’ So David thought I hated his writing. No! It’s just that character. And when you read the novel too, she’s silent. She’s in her head, she’s so depressed, she can barely speak.”

“I’ve always loved that James Cagney quote about acting – ‘Plant your feet, look the other guy in the eyes and tell the truth.’ Julianne conveys the kind of emotional immediacy that creates intimacy and complexity for the audience,” says Savage Grace’s director Tom Kalin.

Moore was upset when The Hours and Far From Heaven were released in quick succession and were lumped together by some, casting her as a downtrodden 50s housewife. “They couldn’t be more different. They’re completely different stories and completely different women.” Barbara Baekeland once declared that her oeuvre – meaning her salon lifestyle – was going down a storm in London. Similarly, if Cathy in Far From Heaven were to use the word, her oeuvre is terrifically successful – a 50s blonde, managing her home and husband with ease, until of course, crisis rocks both. Todd Haynes wrote the film for her, after they worked together on Safe, his extraordinary film in which she is the victim of a “20th-century illness”, an allergy to modern living.

“We are responsible for our tragedies. That’s the way it is in life, it’s not always clear” – Julianne Moore

Moore has a part – “a small part” – in Haynes’s new Dylan film, I’m Not There, playing Alice, a character loosely based on Joan Baez. “I’m really curious to see the movie,” she says of the film in which a host of actors – Richard Gere, Heath Ledger and Cate Blanchett among them – play Bob Dylan. “None of these Dylans are exactly Bob. They’re Bob at that moment, in different periods.” As part of her research, Moore – whose Bob is Christian Bale – read Positively 4th Street, David Hajdu’s brilliant account of Bob and Joan, dubbed the “Liz (Taylor) and Dick (Burton) of the self-righteous set”. “To be honest, you read it and think they are all jerks. What a bunch of jerks. And interestingly, to her credit, Joan talks about that later on. ‘You know, I was very young and I look back on some of the things I did...’ She has an awareness. But Dylan, Bob...” Moore says his names quietly, she is clearly taking sides, as well she might. To cynical eyes it always looked like Dylan ditched Baez – who brought him on stage with her at the end of every show when he was still unknown – as soon as his star began to shine more brightly. “I know people love him, but for me, it’s all very conscious manipulation. Which is okay I guess, but there never seems to be any acknowledgement of that. I’m always so surprised that people go for it.”

When she spoke to her friend, the actress Ellen Barkin for Interview magazine in 2001, the year in which she filmed The Hours and Far From Heaven, Julianne Moore said, “I don’t play the queen or any kind of grand, heroic, mythological characters.” Now, that is perhaps changing. Last year, we saw her as the leader of a band of activists in Alfonso Cuarón’s apocalyptic Children of Men, and she is currently filming Blindness, Fernando Meirelles’s adaptation of the novel by Portuguese Nobel Prize winner José Saramago (which also features Gael García Bernal and Mark Ruffalo). The novel is blistering, a familiar version of the story of what happens when the bomb drops, the flu spreads, the oil runs dry. In this case, it is “white sickness”, blindness that spreads like a contagion through an unnamed city. Moore plays the Doctor’s Wife – the characters, like the city, are not named – who is not afflicted, but allows others to believe she is so that she is taken, with her husband, to be interned in a camp for the blind. The London of the future we were shown in Children of Men was all the more terrifying because it was not so far from the city we see today. Likewise, in Blindness, the horror is on a scale we can recognise, the abuses witnessed over the last century in towns and cities we can name – Belsen, Kigali, Jenin. But while the tragedy just got bigger, these are still personal tragedies. Her freedom fighter in Children of Men was a mother who lost her son. And the doctor’s wife is a woman who makes a family of people the world would tell her are not her responsibility. Indeed, in Saramago’s novel she tells us, “I am not a queen, no, I am simply the one that was born to see this horror.” Julianne Moore looks down at her daughter. Again, it’s so far from her life. “Excellent, a fish tank on the head, that’s nice.”

Hair: Luigi Murenu for Kéérastase Paris; Make-up: Peter Philips; Manicurist: Deborah Lippmann; Photographic assistant: Shoji Van Kuzumi; Styling assistant: Delphine Danhier; Hair assistants: Akki Shirakawa and Akiko Kurizuka; Make-up assistant: Kumiko Hirose; Manicurist assistant: Rica Romain for Lippmann Collection/Salon AKS; Studio manager: Marc Kroop; Lighting technician: Jodokus Driessen; Digital technician: Manoodh Matadin; Production: Art + Commerce; Printing: Pascal Dangin at Box Ltd; Shot at Pier 59 Studios; Special thanks to Art + Commerce.

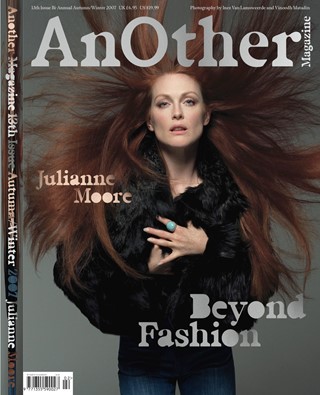

This article originally featured in the Autumn/Winter 2001 issue of AnOther Magazine.