New York is notoriously oblivious to its celebrities, but even here, Sigourney Weaver changes the weather of a room when she enters. Tall, slender, with the bone structure of one of Truman Capote’s society “swans”, she has none of the icicle chill; she’s warm, funny and disarmingly curious when we meet on an ash-coloured, wintry afternoon in the days before Christmas. Untying a scarlet scarf, she chooses the corner table of a mirrored dining room tucked in the back of a fancy Upper East Side patisserie displaying towers of pastel-coloured macaroons in its windows. This blue-blooded, upscale neighbourhood – home to the mansions of Vanderbilt, Carnegie and Whitney – is etched into Weaver’s past: she may be Hollywood royalty but she’s a New Yorker born and bred, coming into the world just blocks from here in 1949, and growing up in a series of homes scattered across the Upper East Side. “And I’m still here!” she says, looking a decade younger than her 65 years, despite a career that has sent her hurtling into the outer reaches of the universe; onscreen, she’s faced demonic ghosts, serial killers, 400-pound gorillas, extra-terrestrials and transformed into a blue, chain-smoking 22nd-century botanist as Avatar’s Grace Augustine.

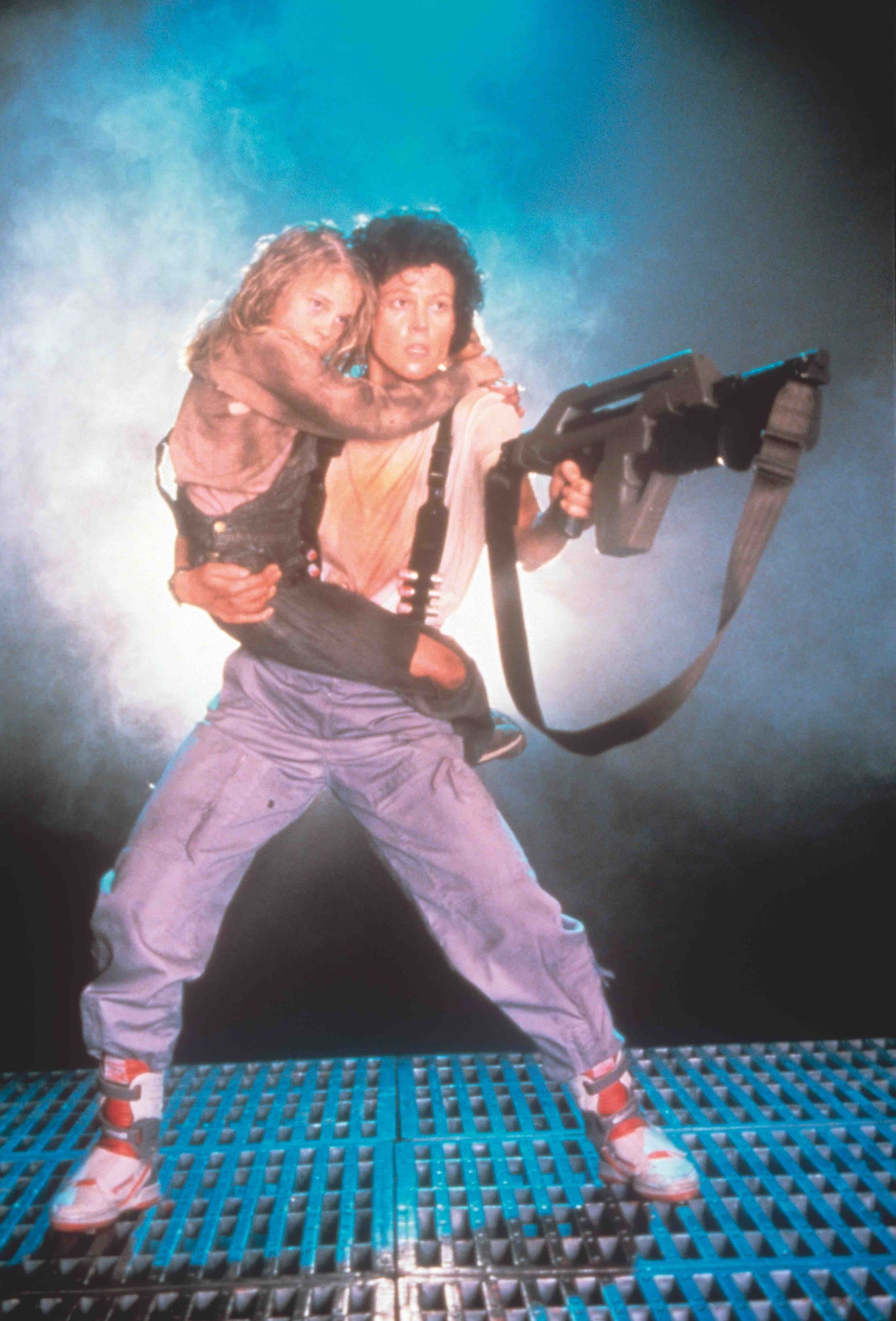

It all began, famously, in a fight to the death with an acid-blooded Xenomorph in Ridley Scott’s 1979 sci-fi Alien. As the sole survivor aboard the Nostromo space-tug, she lived to make three sequels and revolutionised action movies in the process. The taciturn, no-nonsense toughness Weaver brought to Warrant Officer Ellen Ripley gave cinema its first feminist in space, a flame-wielding intergalactic warrior – no shrieking or cute outfits or romantic interest – who paved the way for Terminator’s Sarah Connor, Buffy and beyond. Hollywood conventions have rarely applied to Weaver: an action hero with degrees from Stanford and Yale, she out-muscled Schwarzenegger at the box office at the same time as focusing her light-bulb intellect on arthouse fare with the likes of Roman Polanski, Peter Weir and Ang Lee. She’s as likely to show up in an experimental off-off Broadway play as a summer blockbuster. And if there’s a lack of rom-com in her filmography, you can forgive directors for rarely casting her in “ordinary” roles; it’s hard to imagine Weaver as anything but extraordinary, and no surprise Helmut Newton delighted in photographing the statuesque beauty, shooting the camera a maniacal grin atop a mountain of unspooled celluloid, clad in PVC gloves up to her elbows. Queens, astronauts, political leaders, trailblazing zoologists ... “Well, anyone who works with me knows that I’m totally up for anything,” Weaver laughs. “Just about ... ”

The actress’s early years whisper of privilege, spent between a series of Manhattan abodes and old-moneyed Sands Point, on Long Island’s north shore. She attended the elite Chapin School on the Upper East Side, a private girl’s school with an alumni of America’s most illustrious surnames: a Hearst, a Trump, a Pulitzer and Jacqueline Bouvier all passed through its doors. But aged 12, Weaver might have seemed an unlikely candidate for the Walk of Fame. At that time she was still Susan Weaver (christened after adventurer and family friend Susan Pretzlik), a self-confessed misfit kid, already an awkward 5’11” with unruly hair and her nose in a book. “I was this tall, which was tough,” she remembers. “People would assume I was much older, and expect me to be mature – which is something that still hasn’t quite happened for me!”

“Ripley is not a sexy space babe. I never worried about how I looked, I worried about getting down the corridors fast enough to escape the explosions!” – Sigourney Weaver

Perhaps the turning point began with a name; at 14, she plucked the more flamboyant Sigourney from a minor character in The Great Gatsby, deciding someone of her height demanded a more sinuous sobriquet – her parents opted to call her “S” in case it was a passing phase. Her mother and father were something of an intoxicating double-act: Sylvester Weaver was California-born to a wealthy roofing contractor, and he hung out with the likes of Carole Lombard and Loretta Young before becoming president of NBC in 1953, during the formative days of television. Responsible for inventing both the Today and Tonight shows, he was fêted for his intelligent approach to programming. Weaver’s mother, Elizabeth Inglis, was English – a Colchester-born actress who trained at RADA with Vivien Leigh and became part of the Liverpool Repertory Company before heading for the West End. She’d had a fleeting part in The 39 Steps and co-starred with Bette Davis in The Letter when she set foot in New York just as war broke out. “They met at a party – there were so many parties in those days!” begins Weaver, tucking into a lunchtime croque monsieur. “She was in a play with Jessica Tandy at the time.” Weaver wed Inglis soon after, despite competition from a swashbuckling thespian: “She went out with Errol Flynn for a number of years and he was desperate to marry her,” Weaver remembers. “In fact, I have a telegram dated right after my parents got married. It says, ‘Dear Liz, you’re still the most beautiful girl in the world to me, Errol.’” Inglis sounds like a character Weaver might play onscreen: a beautiful actress who could also kick ass on the tennis court: “My mother was amazing, she could have done anything,” Weaver nods. “She got into Wimbledon at 16, but her father wouldn’t let her play. She was a great athlete, she had such determination, discipline ... she was a force!” But this was the 50s; after her marriage, she retired to raise Sigourney and her brother, Trajan, becoming hostess to a shifting circle of Manhattanites: “Not so much actors – my father was always making fun of actors! But a lot of writers and funny people came by. We had a lot of laughs.”

The teenage Weaver originally planned to become a journalist. An English degree at Stanford tumbled her headlong into 1969 California at its most political, volatile and exhilarating: “You couldn’t not get involved,” she remembers. “Reagan was governor, everyone was being called up with the draft ... I was part of a guerrilla theatre group called The Company, taking Shakespeare in a covered wagon around the Bay Area. We were anti-establishment, commedia dell’arte, ‘bring it to the people’.” Is it true in those years she lived in a tree house and dressed as an elf? “Yes, I did do that,” Weaver laughs. “Sometimes I dressed as a tiger, though.”

Acting, however, was still just a hobby: “I backed into this totally,” she says. “I was driven, but I don’t know that I was driven to become an actress. I thought, I’ll just run around and audition for these drama schools, I’m sure they’ll turn me down.” Instead they all accepted, and she headed back east to Yale – Meryl Streep was a fellow student. But while Streep trod the boards in a number of leading roles, the venerable establishment didn’t believe they had a future star on their hands in Weaver. “They didn’t know where to put me. I was funny, and Yale was not a very funny place,” she says. “I think there was some cruelty going on there. At the end of the first year, half my class were thrown out, and we were put on probation.” Did their obvious lack of faith give her the determination to continue? “Determination is a nice word for it. I hung in there out of spite!” she laughs. After Yale, Weaver returned to New York, rented a basement flat and began to immerse herself in the city’s buoyant theatrical scene, taking to the stage in her friends’ plays: “Unpaid, but fun! To be frank, my parents thought, she’ll do this for a bit and then get a job at Bloomingdale’s.”

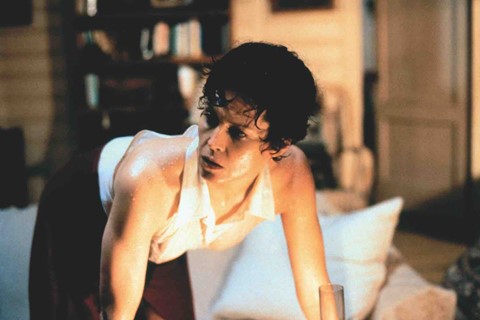

Onscreen, Weaver’s credits hadn’t stretched far beyond a Budweiser ad and a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it cameo in Annie Hall, before she auditioned (in thigh-high “hooker boots”) for a young director named Ridley Scott. When he unleashed the dark, grimy space thriller that sent her stratospheric, she was so new to the camera that Scott had to remind her not to look into it. Alien shot her straight from unknown, too-tall, off-Broadway actress to Hollywood superstar overnight. “When I got Alien, I wasn’t looking to have a film career. I wanted to be a ‘legitimate’ actress, do repertory like my mother had. I remember thinking, don’t worry, it’s a small film, it’s cool and edgy, kind of like an off-off Broadway movie.” (Being Weaver, she put herself into character by imagining she was playing Henry V on Mars, and drew inspiration from the female warriors of classic Chinese literature.) Her character was famously written as a man originally until a last-minute switch was made to wrong-foot the audience. “They thought, no one will ever think the girl’s going to survive! But I was very comfortable with a strong female role, that’s my time, it was all about women’s lib. I’d been put in a baby blue space costume and Ridley took one look at me and said, ‘You look like fucking Jackie O in space!’ We went into this room filled with NASA flight suits and I just pulled this old one out. Ripley is not a sexy space babe. I never worried how I looked, I worried about getting down the corridors fast enough to escape the explosions!” Still, the crumpled grey flight suit didn’t prevent Weaver from becoming sci-fi’s ultimate and most enduring pin-up, and when that suit is removed in the penultimate scenes, a certain section of her audience was forever hooked: “You don’t want to know!” she smiles, when asked about the fan mail she gets. “People do write really crazy things. Science fiction has very ... passionate fans. I tend not to read it any more. It’s a very, very weird thing.”

“The only thing Ripley kept me from doing was love stories. I was a little too intimidating for a lot of producers who wanted a tiny, blonde, blue-eyed girl” – Sigourney Weaver

Aged 30, her sudden A-list status seemed to make no difference to Weaver’s plans; she journeyed straight from outer space to perform in a cult Bertolt Brecht-Kurt Weill cabaret that opened at 11pm off Broadway, co-written with Yale buddy, playwright Christopher Durang. “It’s actually a great asset to go into the business if you’ve been around it,” she says of her insouciance in the face of Hollywood. “You know that it’s not the answer. That fame is not a good thing, necessarily.” But the film offers began to stack up; soon she was flying to the Philippines to play a chic British attaché opposite newcomer Mel Gibson’s hungry foreign correspondent in Peter Weir’s tale of political intrigue in the tropics, The Year of Living Dangerously. Her comic ability got its first showcasing in William Friedkin’s goofy Deal of the Century with Chevy Chase, before slime and marshmallow goo delivered Weaver another mega-hit in Ghostbusters. The role of Dana Barrett was secured with a particularly enthusiastic stab at auditioning: “Coming from the theatre, I didn’t realise that when Dana turns into the terror dog, they were going to do it with special effects. So I became a dog in the audition, jumping around the couch, gnawing at the cushions and howling. Ivan Reitman turned the tape off and went, ‘Don’t ever do that again! It’s so grotesque, an editor might want to use it.’”

Comedy, Weaver says, is what she relishes most – and she’s proved herself a good sport when it comes to satirising her own sci-fi work on the likes of Saturday Night Live. (“Beautiful and willing to be sublimely silly,” as Durang described her.) The comic gene she traces back to her uncle, “Doodles” Weaver, a rubber-faced 50s comedian. “Comedy was king in my family,” she says. At school, towering over her fellow pupils, Weaver had transformed herself into class clown (she was crowned “Freshman Fink” one year). In the film business, her height ensured Weaver took the path less travelled, avoiding the more conventional corners of the business and working instead with many of its risk-takers. “I think the only thing Ripley kept me from doing, was being in love stories,” she muses. “I was a little too intimidating for a lot of normal producers who wanted a tiny, blonde, blue-eyed girl.”

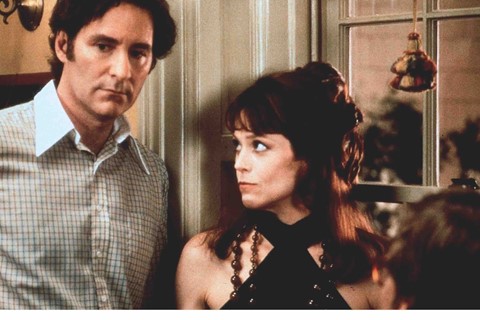

Her range was crystallised in 1989 when Weaver found herself Oscar-nominated in both best actress and best supporting actress categories: the former for the fiery real-life zoologist Dian Fossey in Michael Apted’s Gorillas in the Mist – isolated in a dilapidated cabin 12,000ft up a Rwandan mountain – and the latter as the hair-sprayed, cut-throat corporate climber Katherine Parker in Mike Nichols’s effervescent Wall Street fable Working Girl. She won for both at the Golden Globes: “This is one for the bad girls,” she joked, picking up her award in a fire-engine-red gown. The pattern of balancing big budget (James Cameron’s Aliens had scooped her a previous Oscar nomination), with arthouse and theatre continued: a traumatised torture victim seeking revenge in Roman Polanski’s darkly claustrophobic Death and the Maiden was swiftly followed by a sardonic 70s Connecticut housewife – all jangly earrings, chain-link belts and sheer pink lipstick – in Ang Lee’s The Ice Storm. “I am all over the place!” she agrees. “Well a long time ago, I thought, I’m not going to go after the part, I’ll look for the story. It doesn’t matter how big or small my part is, or the genre, or anything else, I’ll just be involved.”

It’s a strategy that has led to a choppy, fascinating career: during the course of the afternoon, she relates stories that range from the lesson Bill Murray taught her: “I’d try and seriously prepare for a scene and Bill would come over and start tickling me. You had to give up all pretence of being an actor,” to a defining moment in the Virunga mountain range when she first met the wild creatures that would become her co-stars in Gorillas in the Mist: “I guess the producers wanted to find out if I’d go screaming down the mountain. I was so lucky. I had gorillas all over me, jumping up and down, urinating on me. Even when I was charged and hit by a silverback, I knew it wasn’t personal. He was just in a bad mood ... ”

“I was so lucky. I had gorillas jumping and urinating all over me. When I was charged and hit by a silverback it wasn’t personal. He was just in a bad mood” – Sigourney Weaver

These days, Weaver is family to the likes of Ridley Scott and James Cameron: posters for Scott’s latest, Exodus, starring Weaver as an Egyptian queen, plaster Manhattan when we meet, evidence of their continued collaboration 35 years on. The back-to-back shooting of Avatars 2, 3 and 4 is also hovering somewhere on the horizon. Meanwhile a new generation of filmmakers is seeking her out. Last year she flew to South Africa for Neill Blomkamp’s new feature Chappie after admiring District 9, his powerful study of xenophobia and social segregation masquerading as sci-fi. Playing the ruthless head of a weapons company she joins a cast that includes bombastic South African rap-rave duo Die Antwoord. “I was dying to work with Neill, probably more than anyone I could think of,” she says. “To use this medium and genre for less adventure and more social comment is wonderful. We shot in Johannesburg and it’s rough and tumble.” Blomkamp has confessed that watching Alien as a kid was a formative moment – Ripley casts a long shadow. But Weaver seems to have nothing but affection for the character today – she’s kept all of Ripley’s costumes, as well as a baby alien or two. “Old costumes can be like ghosts’ clothing – but I like having Ripley’s,” she says. “The great thing about the big movies I’ve done is they’ve allowed me to do lots of small movies. And they still do.”

They’ve also allowed Weaver to champion her abiding love of the stage. 19 years ago, her husband of 30 years, theatre director Jim Simpson, founded lively Tribeca theatre The Flea (motto: raising “a joyful hell in a small space”). It has attracted a handful of big stars to its minute stage – Tim Robbins, Bill Murray, Weaver herself – but its real remit is to act as a kind of experimental greenhouse allowing new work to germinate. “The Flea is one of the things I’m proudest of. My husband picks all these brilliant young people in New York. It’s wild,” she says, picking up her phone and arranging tickets for the night’s show: “Ten dollars and you get a free beer!”

Later that evening, despite a thunderous downpour of rain, The Flea is a cosy beacon of activity. Drinks are dispensed in the small reception area before an audience spanning young and old are beckoned through a curtain into a tiny theatre. Watching the play that night, a mesmerising two-hander, is like completing the circle: a visceral glimpse into the intense camaraderie, adrenaline and creativity that fired the youthful Sigourney. For the 150 or so young actors here, she’s built the artistic home she wished she’d had in those early years bouncing from one theatre to another, cutting her teeth on the New York scene. Her championing of a new generation also contains a ripple from the past; a reminder of her mother’s days amongst the players at Liverpool rep, and the path Weaver had imagined following before an extra-terrestrial sent her career spinning into a different orbit.

This article originally appeared in the Spring/Summer 2015 issue of AnOther Magazine.