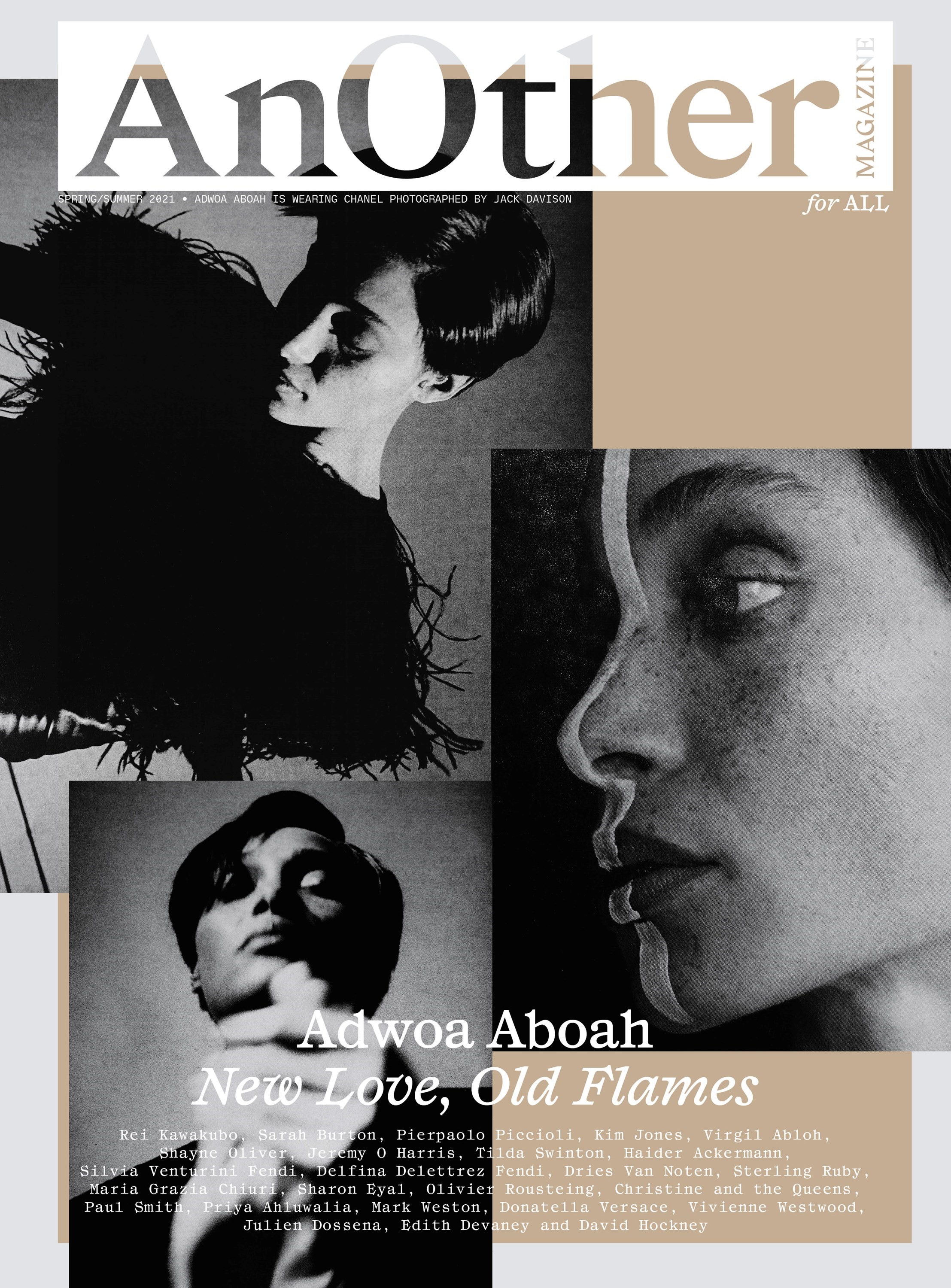

This article is taken from the Spring/Summer 2021 issue of AnOther Magazine. To celebrate our 20th anniversary, we are making the issue free and available digitally for a limited time only to all our readers wherever you are in the world. Sign up here.

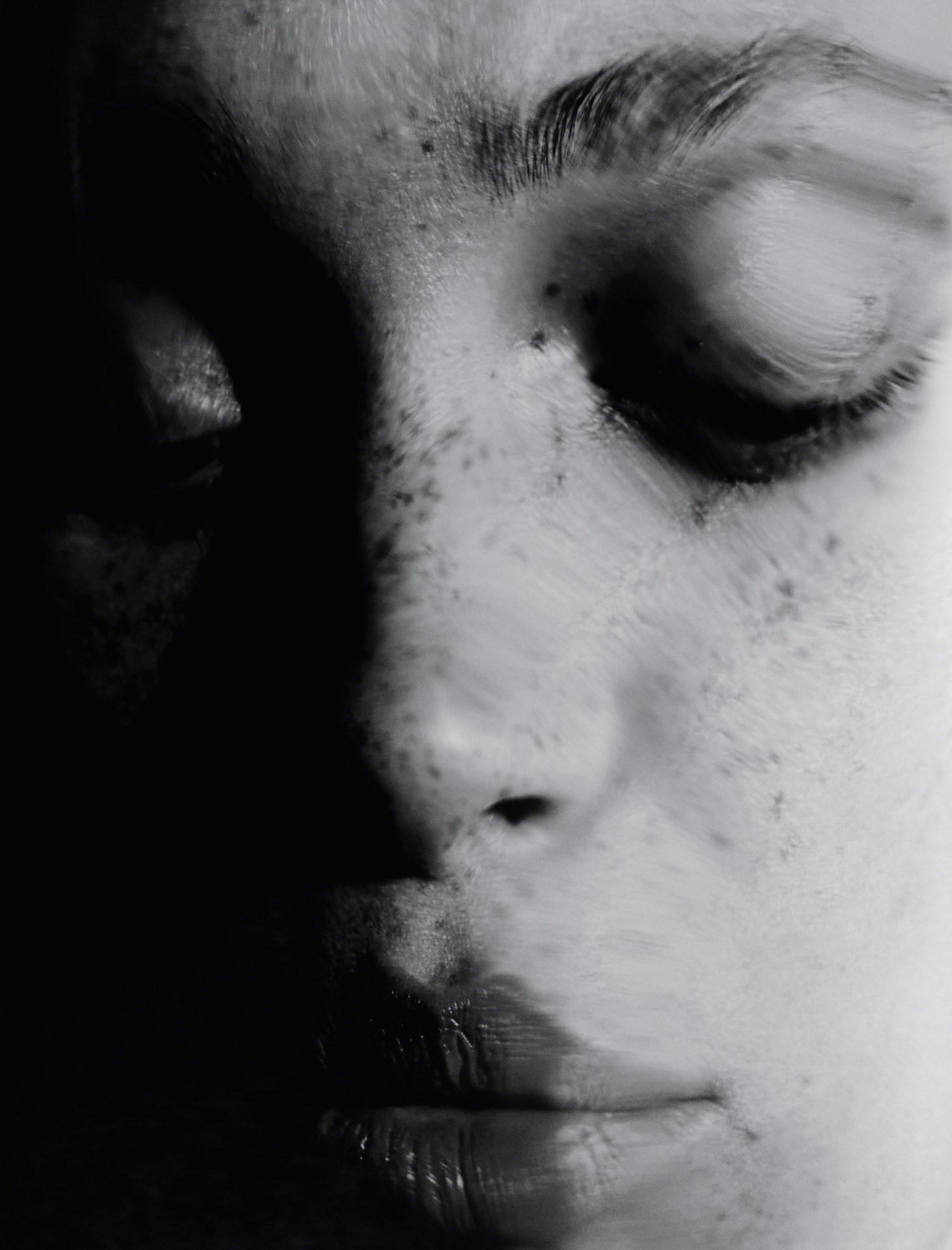

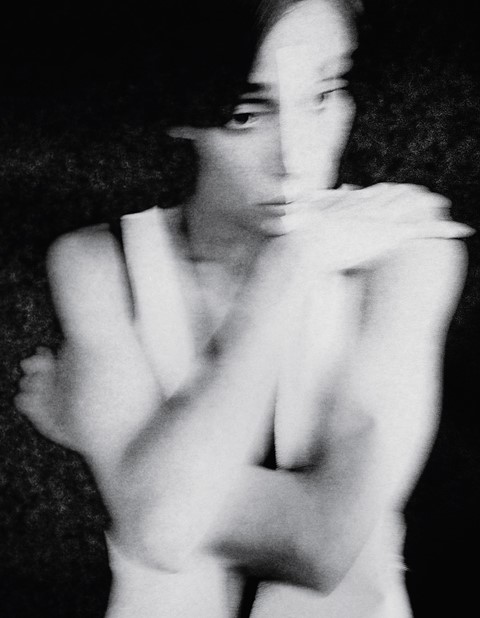

As her one million Instagram followers know, there are few subjects Adwoa Aboah won’t talk about. Her candour and willingness to be openly fragile have fuelled an outpouring of overdue conversations – about mental health, social justice, sexuality and more. Her platform, Gurls Talk, founded in 2016 following Aboah’s own struggles with depression and drug addiction, is a taboo-busting, judgment-free space for young people to grapple honestly with issues large and small, both online and – pre-pandemic – in the all-welcome forums she has held around the world.

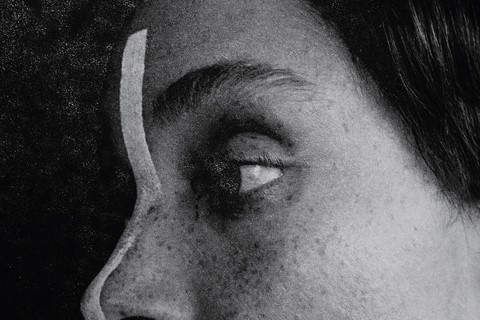

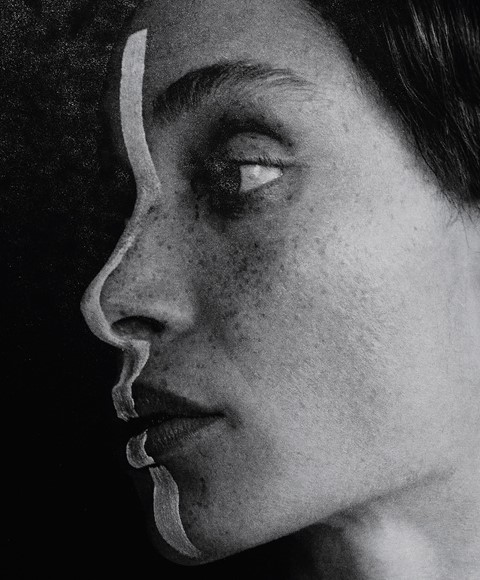

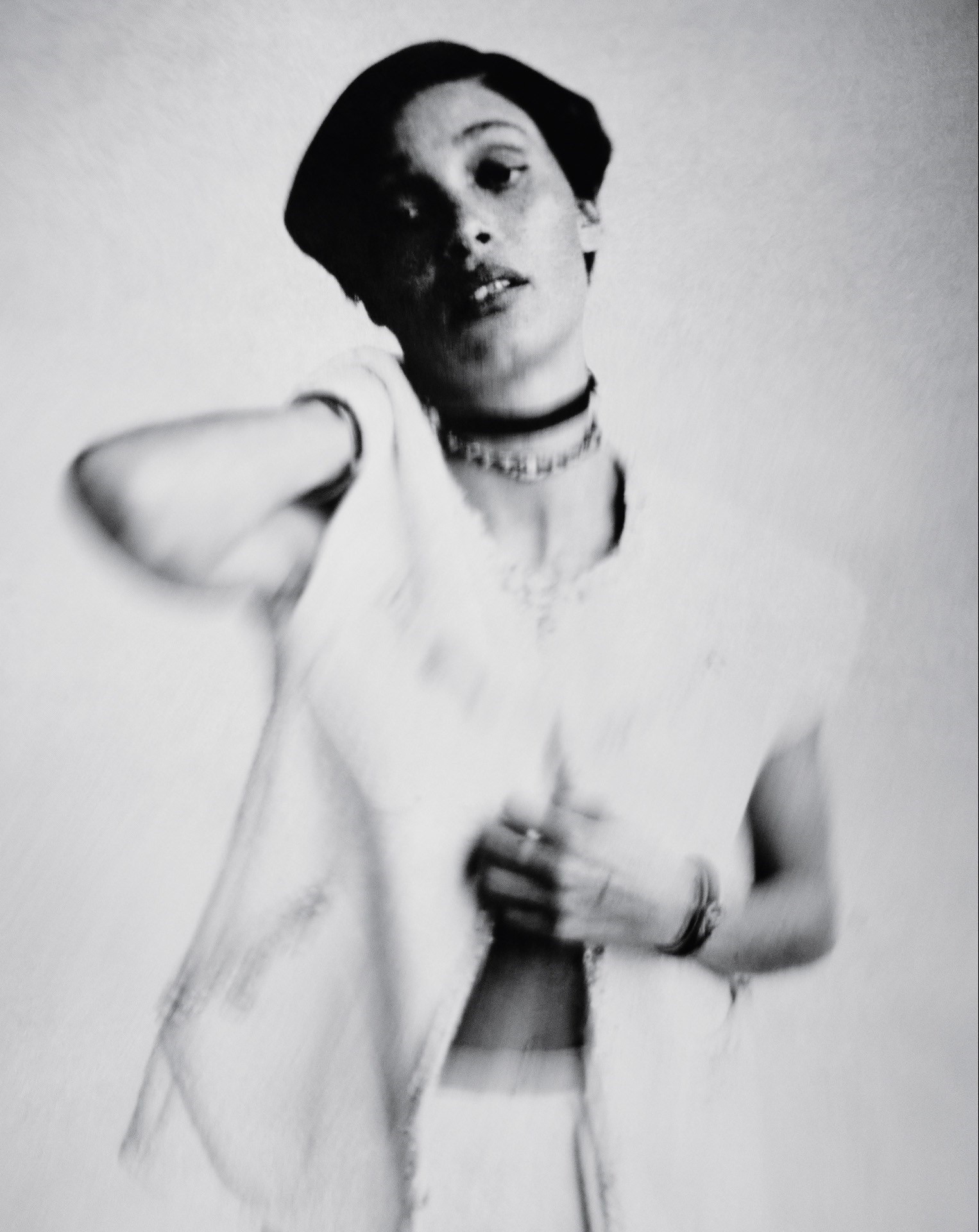

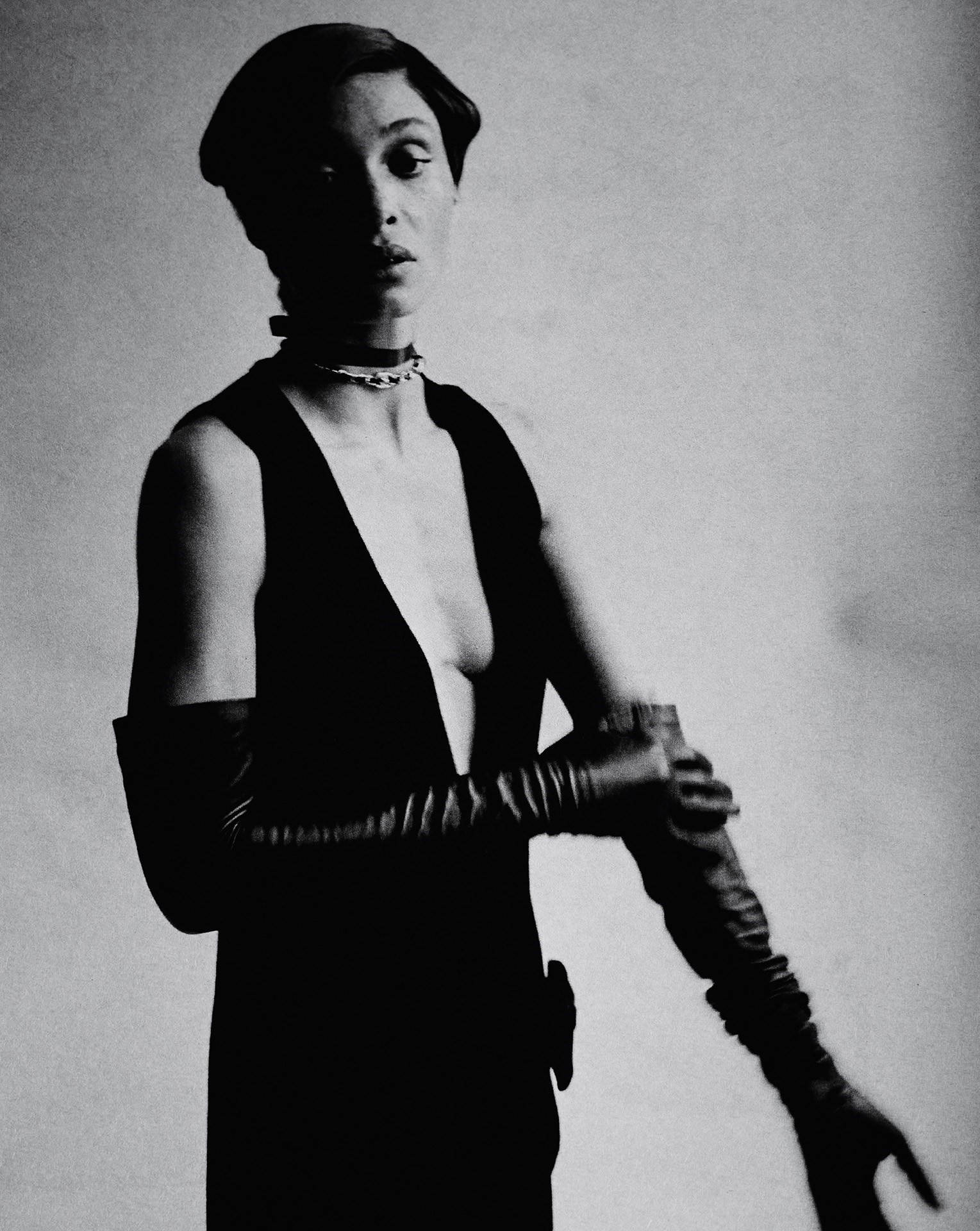

It’s a sign of Aboah’s increasing reach with her Gurls Talk mission that, these days, mention of her phenomenally successful modelling career sometimes runs a close second to her activism. A born and bred west-Londoner (albeit with an unhappy stretch spent at a Somerset boarding school), Aboah grew up around fashion – both her parents work in the industry. She signed to a model agency at the age of 16 and, a decade later, was immortalised in plastic as a Barbie, complete with her now-unmistakable freckled skin, tattoos and shaved head. It was partly that liberating buzz cut – a rebellion against the looks-driven world she was working in, and a venting of frustration after years of feeling she had to tame her ginger Afro for the camera – that catapulted Aboah onto magazine covers and into campaigns for the likes of Chanel, Calvin Klein, Marc Jacobs and Dior. She has used her position in the public eye to hold her industry to account, campaigning for safer spaces, greater inclusivity and body positivity. (She will happily swerve the filter and post a bad-skin day.) But there’s an equally important flipside to Aboah’s vocal advocacy: her ability to listen. That skill is frequently put to use in her raw and intimate Gurls Talk podcasts, during which she guides guests such as the Booker Prize-winning author Bernardine Evaristo and Black Lives Matter international ambassador Janaya Future Khan through a kaleidoscope of topics with empathy and humour.

Aboah finds an unguarded, kindred spirit in Virginia-raised, New York-based playwright Jeremy O Harris. Around the same time the seeds of Gurls Talk were planted in London, Harris was writing Slave Play while still a student on Yale School of Drama’s MFA playwriting programme. The ferocious, funny and profoundly uncomfortable interrogation of the ghosts of white supremacy that resulted from his fevered late-night writing sessions found its way well beyond Harris’s classroom and even the intellectual circles of the New York theatre world – towards the end of its sold-out run off-Broadway, the likes of Rihanna, Madonna, Anna Wintour and Jake Gyllenhaal could be spotted in the audience. A few months later, his play Daddy – an exploration of the relationship between a young Black artist and an older white collector that unfolds beside a Bel Air infinity pool – also opened off-Broadway, while Harris commuted back to Yale for classes. In 2020, Slave Play caused a small cultural earthquake when it transferred to Broadway and was nominated for 12 Tonys, the most received by a non-musical play in the awards’ 74-year history.

Much like Aboah, Harris immediately set about sharing the spotlight, using his success (including a handsome deal with HBO) to support grants for young Black playwrights and donating works by Black writers to libraries across the US. He has an indefatigable way of persuading others to support his causes – he once challenged the talk-show host Seth Meyers in front of a live audience to buy and distribute 20 tickets to Slave Play; Meyers duly coughed up.

Aboah and Harris had never met in person before AnOther Magazine brought them together over Zoom, but Aboah had already identified a like-minded soul. “What I’m always wanting in a conversation is someone completely unfiltered and unafraid, and I see that not just in Jeremy’s work, but also his Instagram and the way he presents himself,” says Aboah. “I just knew our conversation would flow in a different direction.”

Jeremy O Harris: I’m so excited you asked me to do this, because I try to do things where I’m following pleasure, and from everything I know about you, you also seem to be a pleasure-seeker. It’s also wild, because I’ve been on two shoots with your sister. What is it like to be in a family that is celebrated for its beauty? That feels like an interesting family to grow up in. Did you guys always know?

Adwoa Aboah: That’s such a good question. I think you do know, because you hear grown-ups say things like, “Your daughters are so pretty.” But the way I looked at myself was so blurred and confusing I didn’t link that to, “I feel pretty and beautiful.” So I was aware that was a conversation going on around me, but it wasn’t how I felt at all.

JOH: Also, growing up anywhere in the west, it’s going to be difficult for a Black person to feel completely beautiful all the time.

AA: It was when I moved to boarding school that I felt, “I need to start dressing like that,” or, “I need to relax my hair.” Before that I don’t remember caring. But this idea of beauty has taken me a long time. Now I’m like, “Yeah, I’m fit!” It’s not even the modelling, it’s a feeling now.

JOH: You’re about the same age as me – late twenties, early thirties?

AA: I’ll be 29 this year.

JOH: I think that’s the moment you start to feel, “This is the face I have and either I’m going to love it or not.” And choosing to love it is the thing that took me into my thirties.

AA: You’re so right, it’s a choice. I have an acceptance there’s never going to be a week where, every day, I feel gassed about myself. But more often, as I’ve got older, I’m happier to be myself. Don’t get me wrong, I can be trailing through my phone and say, “Fuck, I wish I looked like that.” But there’s something reassuring about deciding that this is what I have to work with.

“The most important thing for young artists is to stay sensitive and open and vulnerable, even in a dark time. It can be very alluring to be closed off right now” – Jeremy O Harris

JOH: I’ve started collecting photographs of writers I’m obsessed with at the same age as I am now, and other pictures of them older. And I’m getting excited about leaning into the fact of being a writer, and less into the worlds I’ve also been a part of, like acting or modelling. I’m really starting to appreciate the idea of ageing gracefully as an artist. My biggest insecurity is the bags under my eyes, which are evidence of the fact that I live a life where I stay up for close to 18 hours a day. If I got rid of those, the evidence would be gone, I wouldn’t look like a writer any more!

AA: I love that idea. It’s the same with smile lines. When I see them on other people, I think it’s so sexy – I think they’re a happy, fulfilled, expressive person.

JOH: So what have you been doing during quarantine to keep up? I know this is the question everyone asks, but I’ve become obsessed with my friends who got new hobbies or really engaged with reading again. What did you do?

AA: I’ve gone through different phases. I tried to paint by numbers. I tried arts and crafts, but I didn’t like it at school and I don’t like it now. Reading, I’ve always been obsessed with, so I’ve thrown myself into that. I’m such a night owl, I’d much prefer to stay up all night and sleep half the day. Having three-hour phone calls with friends has been nice, because I never had the time to do that before. And cooking – I cooked an amazing curried crab soup the other day.

JOH: I feel like a 1950s housewife when I go food shopping. I’ll be in the aisle and get overwhelmed by all the choices and my heart will start beating really quickly – I feel like I’m in a Todd Haynes movie with a camera coming down the aisle at me. I’d rather go to a restaurant and have someone do that for me. I spent the first lockdown in London, so I got to imagine I was some writer with agoraphobia in a new city. But I had a secret, small birthday party where someone came and cooked for me. That was the ideal gift in the pandemic because I hadn’t eaten food I hadn’t made in seven months.

AA: I’ve been spending a lot of the day dancing, from the moment I get up to the moment I go to sleep, with really, really loud music.

JOH: That’s something I miss the most – being in a nightclub, cooped up in the corner, drinking and gossiping, but having that energy of being around other people dancing.

AA: I hope we can do that soon. I also rewatched Game of Thrones for the second time.

JOH: I watched the first season begrudgingly. Then I got hit by a car walking through West Hollywood –

AA: What?!

JOH: Yeah, someone hit me, left me for dead and kept driving. This was how I found out my body rejects OxyContin – I’m really allergic to opioids. So I had to take ridiculous amounts of weed gummies instead. And being as high as I was, in a cast from my knee down, the Game of Thrones universe made sense to me all of a sudden. But I don’t think I could watch that final season again. Speaking of weird endings, how are you feeling about the fact that, this year, everything in your job – the filmmaking, the modelling – has slowed down? Have you started to think, “Maybe this could be a graceful exit for me. I could say goodbye to that and do something else when the world picks back up.”

AA: In the beginning, I needed the break. I felt quite poisonous in my body, and I had no sense of reality because I’d been on a plane and hadn’t stopped for so long. So it was a moment of calm and clarity. But it was quite uncomfortable because I haven’t known me without work for a long time. I had to start rethinking who I was without being busy. And now it’s not necessarily an exit, it’s more that I know what parts of my job I enjoy and I know I need to give space to other things. If I want to pursue acting, I have to say no to more modelling jobs and not let my ego get in the way by thinking I won’t be ‘relevant’ any more. It’s a compromise I’m willing to make. I don’t want my life to only be work any more. I need to have room for my personal life.

JOH: You mentioned ‘relevance’ – I wonder what relevance means to you? Because I had to have a big confrontation with that in the midst of Covid-19. The pandemic started right when I was supposed to have the London premiere of Daddy, which was going to lead into me announcing that Slave Play was coming to London. Then I was going to do a brand new, experimental play in New York that I thought was going to continue elevating some sense of me being ‘the voice of new, exciting theatre’. And in lockdown I was forced to think about myself and my work, and I started to realise that all the ideas I was having weren’t coming from that same, free place that Slave Play or Daddy came from. They were coming from a place of, “What else can I do to freak everyone out? Or stay in front of the conversation?” I realised relevance was the thing I was actually addicted to. What does relevance, or a lack of relevance, look like for you?

AA: In the fashion industry, and definitely being a model, relevance is quite warped and a bit poisonous. The moment when you get your break happens so fast, you’re straight on that hamster wheel. And because it’s so quick, you’re completely terrified that if you don’t say yes every single time, you’re going to lose it. Relevance to me is definitely associated with ego. Recently I’ve said no to things so I can do my acting classes, or my American-accent classes, or things related to Gurls Talk. But then ego gets in the way. I go online and watch a show I’ve said no to and think, “I should have been in that! People will think I’m not relevant any more!” I think relevance is also related to having an opinion. But it got to a point in lockdown where I didn’t necessarily have anything to say. With the resurgence of Black Lives Matter, I felt I should speak, but I was processing so much I didn’t even know how to articulate it all from a personal position.

JOH: My ears pricked up when you talked about your personal life. This year my partner moved in with me, so this relationship that could have fallen apart during Covid-19 got really close, really quickly. But because I was an ocean away from my family, my personal life as a son, as a brother, as an uncle, took a hit. And I felt that even deeper with Black Lives Matter. I felt, if Black lives really mattered, why the hell am I not living in Virginia with my family and my cousins and helping them build their lives differently? Do you think taking a moment to make sense of these questions around Black Lives Matter also brought you to thinking about your family in different ways?

AA: Oh, 100 per cent. It was definitely a much-needed conversation with myself, and one I have a lot with my sister and my dad. But it was really uncomfortable. I had let a lot of things slide for too long and I felt my soul had been chipped away. I had to look at people around me, and it was like the blinkers had been taken off. I was looking at what it meant to be both Black and white, and I was feeling quite alien. There were days when I felt, “I have no idea who I am.” Situations came up where I didn’t feel Black enough and I didn’t feel white enough. Having to look at my identity in that way was really painful and uncomfortable. But it was good, actually, because I took a step back. And going back to relevance, I think relevance is the thing that keeps you trapped. So when life slowed down, I had the time to say, “I don’t need to test myself.” I’m quite an overachiever and I love a challenge, but I thought, “We’re all in fragile states and I don’t need to test myself right now.”

“Keep that empathy. I think we’re allowed to feel what we feel right now. There is so much uncertainty for all of us and it comes in many different shapes, so sit with that and don’t push it away. Be frank with yourself and don’t feel like you’re not justified in feeling whatever emotions you’re feeling” – Adwoa Aboah

JOH: I’m trying to shift gears and figure out how I can make this year different for myself. I have this space where I come every day for five hours straight to journal, read and write whatever the fuck I want to write. Do you have any plans?

AA: That thought didn’t even cross my mind until February. January was dire – I was binge-watching, not sleeping, I overdid the exercise and fucked my knee. I was not in a great place, isolated and living by myself. But now I feel more willing to figure it out. I have daily talks with myself – I say, “It’s OK if today wasn’t good, tomorrow will be better.” There are little things I can do – I’ve been mood-boarding projects, going on Pinterest and creating a jewellery collection or a made-up fashion brand or a documentary idea, just putting things together. Because what I’ve found hard is I always felt like I had lots to talk about. But in January I felt I didn’t have anything to offer – “Today I stared out the window, I have nothing to report back on.” So now I’m just trying to be curious.

JOH: I was so negative at the top of this year. I could go into deep detail about how everything anyone liked had no worth. But I thought, “Jeremy, you were gifted with a critical mind, don’t waste that criticality on negativity.” I realised so much of that was about me feeling upset about the work I wasn’t doing or wasn’t able to do. And shifting those paradigms in my mind helped me feel better. My chest lifted, but it was really dark for a while. And it’s a darkness I was seeing a lot on Twitter.

AA: Really? What were the conversations about?

JOH: Every week it was, “The worst film ever came out and these actors should know better.” And a lot of it was about Black work, which really enraged me. Because I want us to feel excited about people being able to fail publicly again. The most important thing for young artists is to stay sensitive and open and vulnerable, even in a dark time. It can be very alluring to be closed off right now. Finding those people in your community who can be an extra arm to lift you up, and you can be that for them, is the most important thing. That’s what Gurls Talk is about too, right? One of the things that social media and the search for relevance does to a young artist is make it feel like this is a one-sum game, and a game you can only win by yourself. But I know that if I hadn’t had the committed friendships I’ve had for the past decade, none of the stuff that’s happened with me would have happened. It seems so lame to say, but make good friends, cut out the ones who don’t matter.

AA: I think so. Keep that empathy. I think we’re allowed to feel what we feel right now. There is so much uncertainty for all of us and it comes in many different shapes, so sit with that and don’t push it away. Be frank with yourself and don’t feel like you’re not justified in feeling whatever emotions you’re feeling.

JOH: Adwoa, I could Zoom with you all day.

AA: I could with you too. This is exactly what I thought would happen – we went nowhere and everywhere.

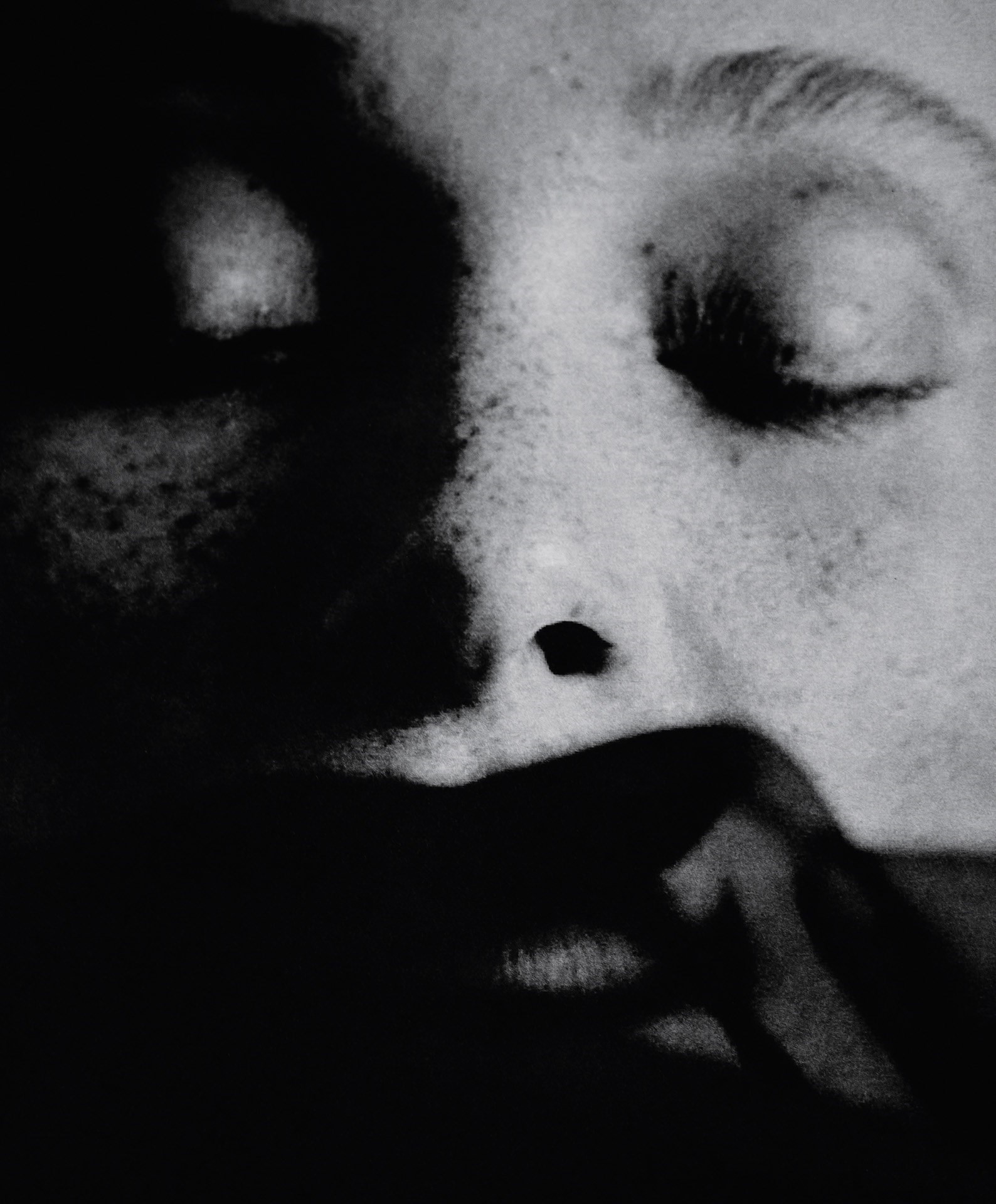

Hair: Virginie Moreira at Management Artists. Make-up: Celia Burton at JAQ Management using Rouge Allure Laque and Le Lift Lotion by CHANEL. Model: Adwoa Aboah at Tess Management. Casting: Noah Shelley at Streeters. Set design: Alice Kirkpatrick at Streeters. Styling assistant: Rebecca Perlmutar. Production: Mini Title

This article originally featured in the Spring/Summer 2021 issue of AnOther Magazine which will be on sale from 8 April, 2021. Pre-order a copy here and sign up for free access to the issue here.