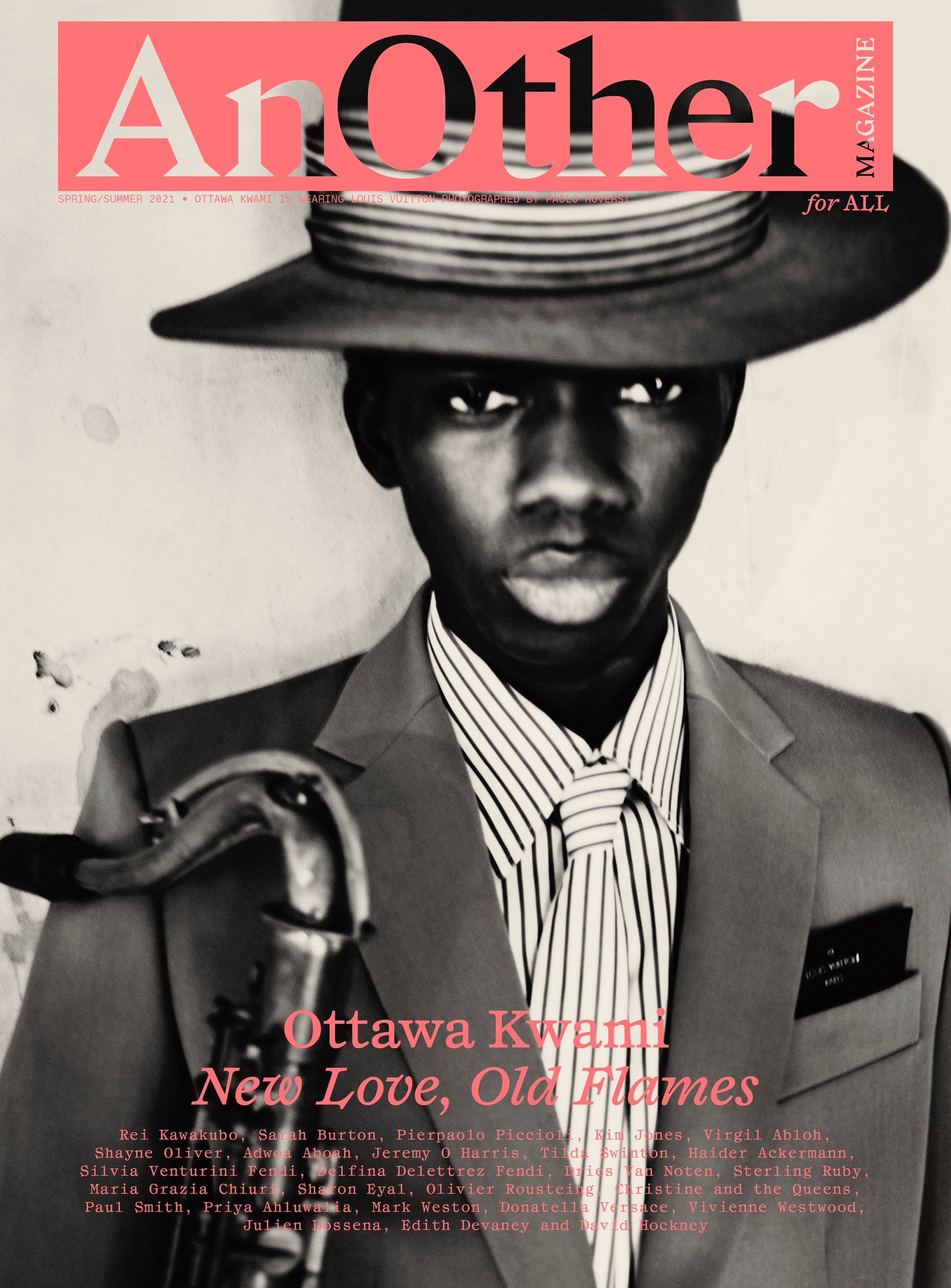

This article is taken from the Spring/Summer 2021 issue of AnOther Magazine. To celebrate our 20th anniversary, we are making the issue free and available digitally for a limited time only to all our readers wherever you are in the world. Sign up here.

It was a T-shirt that predicted fashion’s future.

That T-shirt was an off-the-cuff collaboration in 2012 between upstart New York label Hood by Air, founded in 2006 by Shayne Oliver and Raul Lopez, and Been Trill, the art and DJ collective that included Virgil Abloh (then best known for his label Pyrex Vision), Heron Preston, who launched his eponymous brand in 2017, and Matthew Williams, who founded 1017 Alyx 9SM in 2015 and, last year, became creative director of Givenchy.

Black and emblazoned both with Been Trill’s dripping Rocky Horror-font branding and HBA’s logo, it had an effect that, spurred on by still-fledgling social media and it being seen on Kanye West, soon snowballed beyond the garment’s intended audience, placing its creators firmly in the spotlight. An expression of downtown New York’s melting pot of music, culture, clothing and nightlife that was the backdrop for its creators, its hype-generating design foreshadowed what was to come in fashion, both literally and figuratively.

In a matter of years, graphic-driven ‘streetwear’ would dominate the industry, with luxury houses running to keep up. Oliver would win acclaim for HBA’s collections, showcased at New York Fashion Week, while Abloh would go on to found Off-White and lead Louis Vuitton’s menswear.

Despite establishment approval – Oliver has taken home the LVMH Special Jury Prize and a CFDA award, and Abloh’s Off-White, bolstered by partnerships with the likes of Nike, has become one of the most coveted brands of the past decade – the two designers, both Black and American, struggled to have their work taken seriously at first, let alone understood. Oliver’s output – a confrontational blend of conceptual high fashion, hip-hop, club world and ballroom culture that resulted in voguers, Pornhub logos and double-footed cowboy boots appearing on his label’s runways – was often categorised simply as disruptive. Comments directed at Abloh, meanwhile, centred on his perceived unoriginality, or snidely accused him of not being a ‘real designer’.

While Abloh has blazed a trail at Louis Vuitton, Oliver has partnered with brands including Helmut Lang and Diesel, and has just relaunched HBA, which he had put on hiatus in spring 2017. He’s also been working on Leech, a shapeshifting concept that simultaneously combines and transcends music, art, fashion and performance, and Anonymous Club, the multidisciplinary creative studio and talent incubator that develops all of HBA’s visuals and content – as well as collaborating with resident artists and other partners. But all Abloh and Oliver’s work is a continuation of the conversations they started years ago, when discussions of race and identity remained conspicuously off the fashion industry’s radar.

Through it all, they have stayed friends. And when AnOther Magazine asked Abloh who he would like to be in conversation with for this issue, he had just one suggestion.

Virgil Abloh: Legitimately, when this came through, I was like, there’s only one person I can talk to [Laughs.].

Shayne Oliver: That’s what I was thinking too. Obviously, we’ve known each other for so long.

VA: We’ve been at this exact space – let’s not call it fashion, let’s just call it people producing ideas – for the past ten years. And now there’s been value placed on ‘fashion’, placed on ‘Black’, and there’s been value placed on what we identify ourselves with, and we’ve just been outputting, consistently true to ourselves, when no one was watching, all the way until now. Any questions people would have asked us ten years ago, we would answer the same now – the only thing is now it’s recorded on Zoom.

SO: We met at a time in New York when everyone was crossing paths. Through meeting Matt [Williams], and really just being in the arena where ideas usually flourish, which is downtown. Not because of the cachet of downtown, but because of people just being open to each other’s ideas – everyone was sort of figuring out what they wanted to interact with, and what made sense for their worlds. With fashion, you enter it and it’s like, all for fashion. I think that was what was intriguing about that space – we had ideas to bring to fashion, but not specifically for fashion.

“For 2021 the pressure’s off. There’s nothing more satisfying than instead of looking for acceptance, or looking for a fairy-tale existence, all of a sudden realising there’s no gatekeeper” – Virgil Abloh

VA: When we both started, we were kind of the outsiders making noise. And then the industry started paying close attention to it. We were telling our own stories. And when people find things viable in that, they’ll call it a word, they’ll take control of it, they’ll try to make a trend.

SO: And in the beginning, everyone thought it was gimmicky because no one really understood what the reference points were. Fashion likes to have pop words and things they can grab onto, to feel like they’re building a moment. So people can link adjectives to clothing, you know what I mean?

VA: Right. Obviously, we’re both Black and American, which are characteristics that are important to our story, as that transcends time. It could be trendy in a moment, it could be at the forefront, then there could be an attempt to unravel it by calling it streetwear or whatever, and the cycle keeps on going. In a year like 2020, when the outside world was trying to say, “Hey, we want to be inclusive, we want to be diverse,” you could forget about the existence of the narratives that we were telling. These talents were coming through in the years before 2020, and we’re still here, we’re still creating.

SO: A lot of times, fashion has dealt with Black conversations only through trend conversations. But the conversation that a Black person is having is not a one-time conversation.

VA: Right.

SO: It’s like, we’re here, we’re creatives, we’re not going to be here and then go away. There are multitudes of European designers and there are multitudes of Black conversations. These conversations are valid because they’re continuous, actually, and we’ve been here for a while, trying to create that landscape for those kinds of things to be taken seriously.

VA: What you see, between you and me, is two of a multitude of approaches to bearing the weight of, “You’re the trend for the moment,” or, “You’re the outlier,” or, “We’ll let you in to occupy this space.” Or, “We’ll try and trend-ify your movement.” Or, “We won’t really count it next to the European canon, but we’ll let it live just to spice it up.” What people fail to realise is that we’re often not understood. We have a huge weight to bear for our own community and our own sets of minorities that we represent. But also, on the other hand, we are often slighted, or not given the proper space to just have the idea sit.

SO: That’s partially why I took a hiatus, because I want to be able to create a space for myself so that people can have a chance to speak about the world of what I represent in a more serious way than season by season ... I think that, now, I’ll be able to have more of a language and conversation via my work, because people will be educated on it.

VA: We could sit here all day and recap on the nuances of what the media or the critique [of our work] misses, or just its bias. The right mind can see the adjacency between myself, Kanye, Jerry [Lorenzo, of the label Fear of God], or [rising label] Bstroy, these kids in Atlanta. It’s like, we see Air Force 1s as a Tabi boot, do you know what I mean?

SO: [Laughs.] Yes!

VA: We see the barbershop, we see kids get shot, we see police, we were born with a different eye to the world. And then we each individually – Kanye to his, you to yours – packaged up our DNA of design. There’s a lineage between us that maybe a journalist just hasn’t put the categorical term on, but we can’t be preoccupied with that.

SO: What’s so funny is, even when it comes to design, it’s a physical feat, like a struggle, in a sense, where within the production routes you’re working with, no one even understands the things that you’re inspired by. So there’s this uphill battle of, “Why is this important? Why is this being made?”

VA: Arthur Jafa broke it down in a very simplistic way. He was like, Black people are born conceptual artists.

SO: Yeah. Mmm.

VA: He was like, pressure creates diamonds, right? So when you’re born, you just hop on Earth at a young age and don’t understand, you don’t know, the systemic rules of the world. You only feel those when you go to school and some kid says, “You must behave like this, you must talk like this, you’re a different human being.” And then that pressure, as you grow older, it just keeps crushing down and it creates diamonds. So when we output, we conceptually do this calculation that inherently comes through our skin and our perception of our skin. So for me, instead of being hardened or pessimistic, driving myself crazy, as a profession like this can make you, that idea just sort of reorganised my operating system.

“There are multitudes of European designers and there are multitudes of Black conversations. These conversations are valid because they’re continuous, actually, and we’ve been here for a while, trying to create that landscape for those kinds of things to be taken seriously” – Shayne Oliver

VA: Now I always want to centralise this conversation about the missing documentation of a new voice within fashion that predominantly comes from Black culture, from pop culture, that has never been documented in a profound way. I never went to school and found a book that taught me about that in the same way I know about Leonardo da Vinci, or Yves Saint Laurent, or the way I know about Margiela. In January, I started making this sort of oracle book – it’s a figurative book, not a literal one – called Black Canon, a textbook that no one has ever made, or read, to understand why Black culture is fascinating in an artistic-production sense.

SO: It’s also this idea that there is a line of people who are using the same modes of communication, and every time [one] gets broken, that research library gets erased. So we always have to redo that library and, right now, it’s about keeping that library consistent. So when kids are coming up who aren’t surrounded by those same influences, they understand that there’s...

VA: ...A bible that you can’t erase. Not an Instagram video, right? Like, shit happens and then it disappears. And then someone can say it didn’t actually happen, because it’s not there any more. When we were teenagers, we obsessed about shit on the internet, music videos, websites, and you realise if you type in those URLs now, they’re not there.

SO: Totally.

VA: If it’s not frozen on the internet for 30 years, people will just rewrite it. So that’s what really woke me up. It’s not about what’s popping today. It’s that our archives are strong, that they are built, printed, verbalised and contextualised – that they can't be erased. It’s like, shit, I’m at Louis Vuitton. I’m not gonna make it to Louis Vuitton and be like, “I’m not gonna come out at the end of the runway because I just don’t want that pressure.” I’m gonna do that because I want other people to see that we’re active and given the opportunity. There’s a responsibility that I have to my whole community.

SO Where we’re coming from, you produce so young – the diamond pressing. We get so used to that high level of producing. Because anything that we present has to be stellar, you know what I mean? What you’re saying with this book is, whether it’s physical or not, it’s very, very important.

VA: And when you zoom out, you’ll see that I was making this book this whole damn time, right? All of a sudden HBA is linked to Ye, is linked to the countless soldiers from all the parties, you know, from Total Freedom, Arca to Venus X, everything. It’s this web. People think my career might be just me, I’m just scribing in other people’s books, it’s graffiti. It’s like, we have to write graffiti on every wall. That’s the learning of a steep ten years of understanding.

SO: But if it’s not documented well, the next person will have to start over, regardless of where we’re at. Period.

VA: I talked to Dapper Dan and it disheartened me. This man is still alive and there’s a 14-year-old in Chicago who doesn’t know who he is. I go to Instagram, and I say, “How many kids have read this Willi Smith book [Willi Smith: Street Couture]?” They’ll be like, “What are you talking about? Show me the Raf book!”

SO: In this hiatus, I was like, I need to make this moment work for me. What do I need to know about myself? Back in the day, I would be like, “Oh, it would be great if I can work with this artist.” Now, with this new phase I’m moving into, I can’t wait on that person to exist – I have to be that artist, I have to be that musician. Those years [at HBA] were my youth. People didn’t understand that that was actually my twenties. And I didn’t realise that I was the artist at the time. It took me until this year to understand that.

VA: When you don’t have access to production, everything is a ready-made. I know the canon of HBA, so I know that there’s a platform Air Force 1. I’ve said it 30 times but the Air Force 1 is a Duchamp urinal. It’s a loaded object and we know what it means. We know what it means in Harlem, we know what it means downtown, we know what it means all white, we know what it means all black. We know what it means. What we’re saying is that streetwear, as a collective consciousness of production, has already run its course – it’s on its hero’s journey. I said streetwear was dead for a reason. To give me space. But also to give space to those of us who are sitting in our studios, seeing a scene that we partook in ten years ago now evolving into a multibillion-dollar business – seeing fashion houses that were trying to say that we weren’t fashion adopting our DNA. Now we’re slipping into our 2.0 mode of production.

SO: Mmm.

VA: Now we realise that we can tap into the furthest extremities of our creative brains. It doesn’t need the wow factor of 2020, which is, “Oh shit, he collaborated with, you know, ‘legend brand’, or something we didn’t think of,” because that shit is tired.

SO: [Laughs.] Yes!

VA: That came from when we had no access and needed those ready-made modes of production. That’s passé now. And what I’m excited for is Leech, seeing what that is, because I have no reference for it. Or Anonymous Club, which is like mutual aid, it’s community service to the highest degree. So that younger kids don’t feel like they have to go through the gauntlet to express themselves.

“I want to see this as a renaissance. I want to see some non-genre-defining amazingness, because I believe that our generation has that. I can’t wait to see what the pressure from 2020 built” – Virgil Abloh

SO: What I’m hoping for with Anonymous – and speaking openly about that process – is that the kids can become more comfortable with making mistakes. I think that, right now, with Instagram, it’s just about perfection. Meanwhile, the people they look up to have flip-flopped all over the place throughout their careers. Me doing fashion concepts and all that stuff in the club world allowed me to learn about myself and learn my practice, so that I could then formalise it and do it in more of a fashion context.

VA And in our ecosystem, there is no sort of discipline, and that’s what makes it unique. As long as there’s space for these ideas to exist – your music project, whatever I do – I’m happy and confident, you know? For 2021 the pressure’s off. There’s nothing more satisfying than instead of looking for acceptance, or looking for a fairy-tale existence, all of a sudden realising there’s no gatekeeper. I know what I need to create with my time.

SO: It sounds so backwards to say, but you have to break a lot of disciplines in order to create a new version of a discipline.

VA: Like if you have a modern car, you don’t put the key in to turn the engine on. You just push a button. Fashion is still trying to start the car with a key.

SO: To me, that wonky old key is taste, right? And it’s this idea of, “Oh, no, that couldn’t work because it doesn’t look like this key that’s in our hands, so it couldn’t be the way to turn it on!” But fashion needs to make what might be considered ‘distasteful’ moves. When conglomerates first began to invite younger designers in, it was very, “Whoa, what is that decision?”

VA: What fashion before this era had was real renegades, whether that’s Gaultier or Alaïa, Galliano or Marc Jacobs, who is the forefather for me – they’re exuberant, plus, “Hey, I can do the conglomerate thing.” Those young talents are here today. You are one of them.

SO: Take Margiela at Hermès. For me, that’s what started these conversations that are now so mainstay, you know, and no one’s taking those risks.

VA: I think if fashion becomes a hotbed for the conversation, rather than the consumer and the trend centres dictating what’s cool, it can make those risky moves and find avant-garde, true talent that’s in the shadows. You know, there are amazing kids coming out of London, I’m sure – RCA, Central Saint Martins. But there are also kids coming from Atlanta. There are kids coming from New York, Brooklyn, the Bronx, who are Black kids, maybe with no formal training.

SO: When things are running amuck, people tend to go traditional, and it’s weird to see when people take that route. We have to reflect the times. We have to create that renaissance.

VA: What I’m excited about is the non-judgmental space. I don’t believe in genres, or disciplines of creativity, I like when they blur. I want to see this as a renaissance. I want to see some non-genre-defining amazingness, because I believe that our generation has that. I can’t wait to see what the pressure from 2020 built.

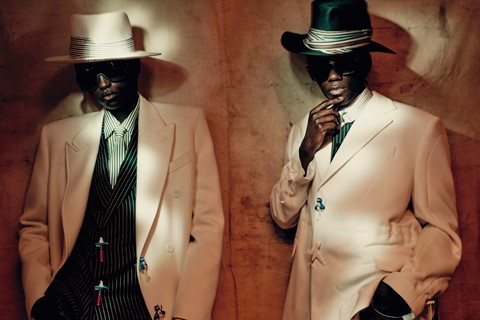

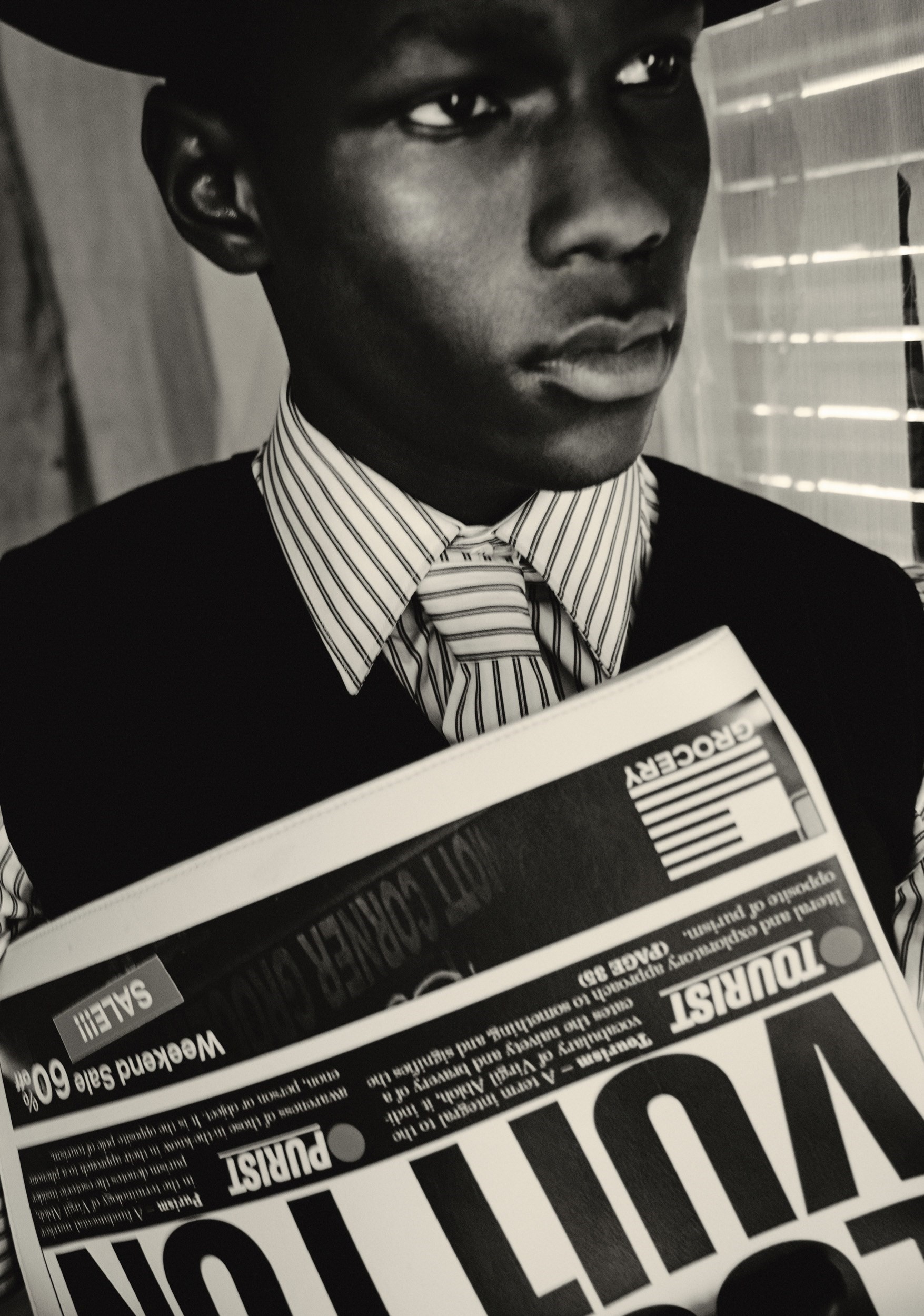

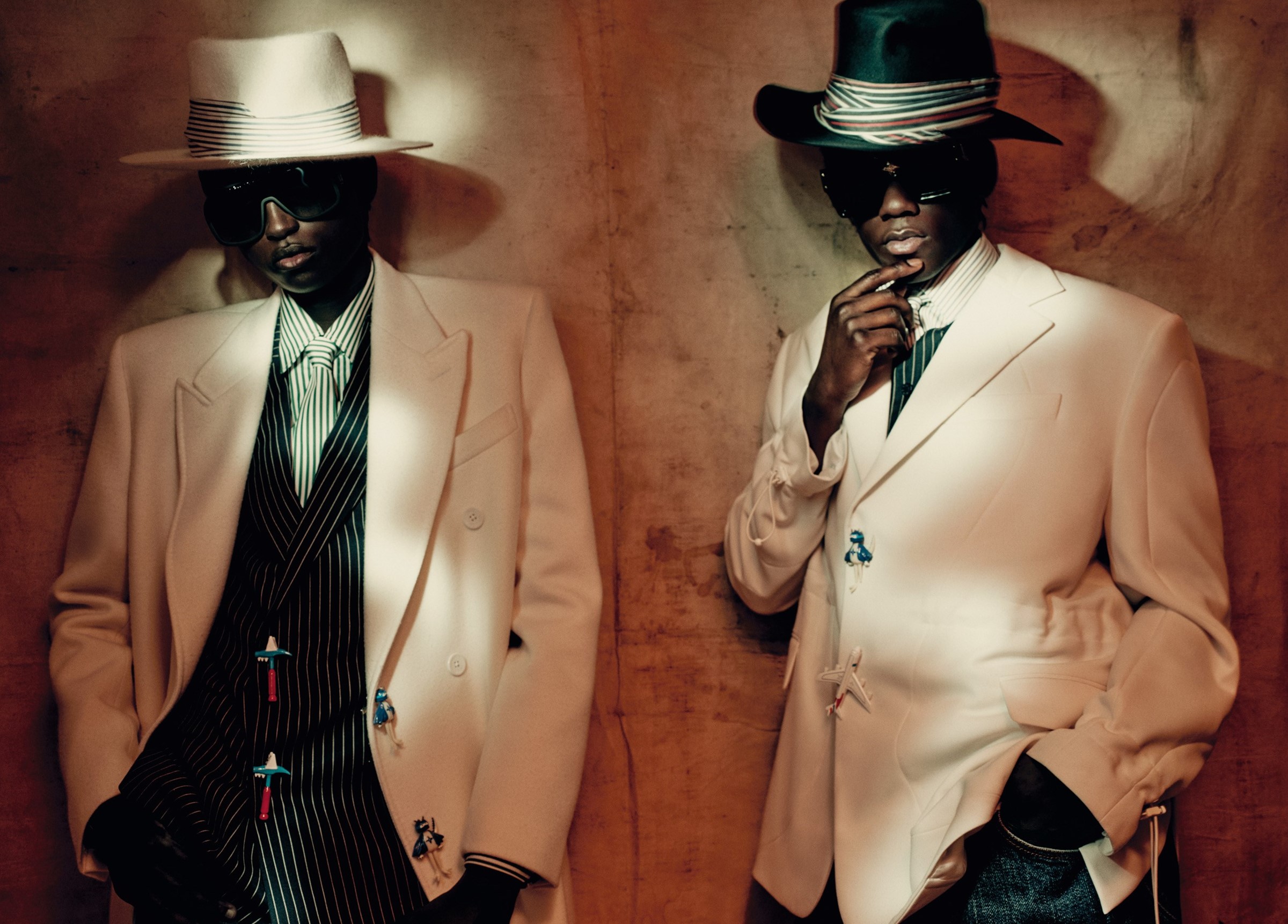

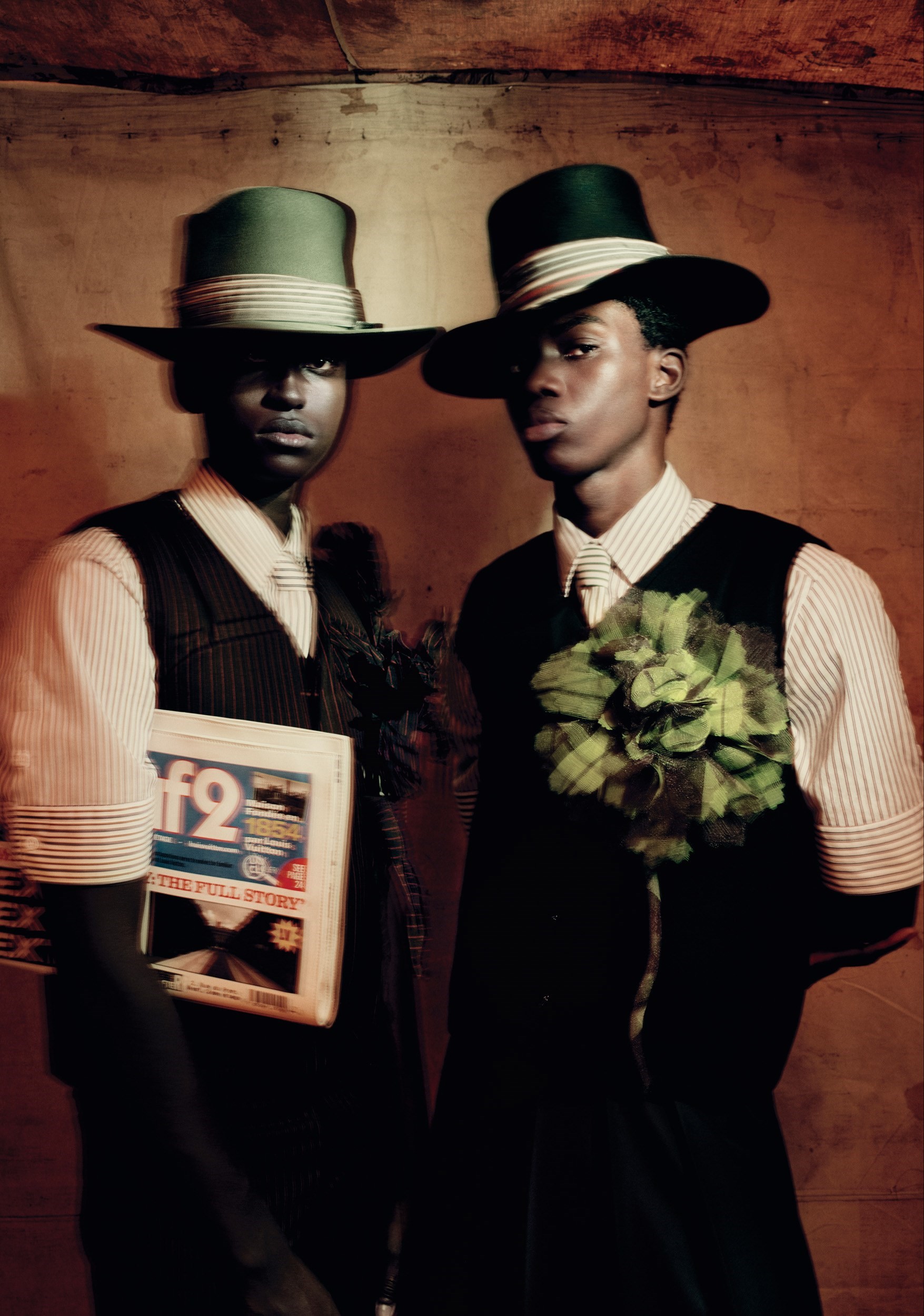

Hair: Odile Gilbert at Atelier68. Make-up: Hiromi Ueda at Art and Commerce. Models: Cheikh Dia at Models 1, Djily Kamara at Bananas Models, Ottawa Kwami at Premium Models, Rayan Lazac and Ismael Savane at 16Men, and Kestelmann Toussaint at Success. Casting: Mischa Notcutt at 11c Casting. Set design: Jean-Hugues de Chatillon. Manicure: Alexandra Janowski at Artlist. Digital tech: Matteo Miani at Dtouch. Photographic assistants: Clara Belleville, Chiara Vittorini and Carolina Beccari. Styling assistants: Felix Paradza and Mark Mutyambizi. Hair assistants: Taan Pham and Hugo Raiah. Make-up assistants: Miki Mastunaga and Camille Basson. Production: Studio Demi. Post-production: Dtouch

This article originally featured in the Spring/Summer 2021 issue of AnOther Magazine which will be on sale from 8 April, 2021. Pre-order a copy here and sign up for free access to the issue here.