Today, the jockstrap is a seminal garment in contemporary gay culture. On the face of things, this shouldn’t be much of a surprise: it typically features a pouch at the front, simultaneously concealing and revealing the crotch, while two straps push up the butt cheeks. Nowadays, it’s hard not to see a jockstrap as a very, very gay item of clothing, but it might seem strange to some, given its origins. The design first emerged in the late 19th century, when it went by the name “bicycle jockey”, created to give cyclists extra support when pedalling over cobblestoned streets. After that, the garment became popular among players of rugby and American football, before being adopted for gay men.

Until recently, brands like Aussiebum and Andrew Christian were the go-to places to buy jockstraps in a variety of colours and fabrics. Nike has a popular design too, in a classic black. But fashion labels have started releasing their own designs: Calvin Klein released a Pride collection of multi-coloured jockstraps, explicitly referencing its popularity among queer men. This year, Rihanna’s Savage X Fenty released jockstraps for Pride, too. The mainstream visibility of jockstraps as a gay signifier reached a crescendo in 2020 when Lady Gaga released a limited-edition Chromatica jockstrap, in an intergalactic shade of pink, to promote her new album. Gaga’s legion of queer fans were given the option of purchasing the jockstrap and album together, and social media was duly flooded with photos and memes alike.

Jockstraps are an item steeped in functionality, both in terms of its original use in sports and now in sex, but designs are quickly becoming more decorative. French designer Ludovic de Saint Sernin created a range of luxury jockstraps in lambskin leather, which feature additional lacing at the front too, adding another layer of suggestibility. He tells AnOther that his jockstraps have been one of the most requested items by the brand’s followers on social media, and that they might even be ushering in a new era of sex positivity in fashion. “The underwear we do is heavily inspired by Robert Mapplethorpe’s photography and the NYC scene at that time,” he says. “Fashion loves to take inspiration from subcultures and there’s definitely a growing movement of sex-positive fashion rising and shining light on sexual freedom and acceptance which I think is really inspiring. It’s still very niche obviously for the moment, but it’s great to see that it’s making progress and gaining visibility.”

To De Saint Sernin, the appeal of the jockstrap to gay men is rooted in both functionality and its old-school athletic connotations. “What guys love about it is the fact that it’s underwear, sure, but it’s also something you can keep on while you are in action,” he says. “It’s revealing yet protective at the same time. And it’s got this whole sports aspect of it which makes it even hotter.”

It seems clear that that there is a link between sports and the gay infatuation with jockstraps. Sports are perhaps the most visible expression of the ideals of masculinity in our society, and have traditionally acted as a training ground on which boys are taught what it means to ‘be a man’. Brian Pronger explores the homoerotic undercurrent subliminally present in the masculine “struggle of sports” in the book The Arena of Masculinity: Sports, Homosexuality, and the Meaning of Sex. Pronger argues that athletics have become both a “metaphor and reality” of American masculinity in particular, but that it’s also a space where gender norms are being contested and transformed.

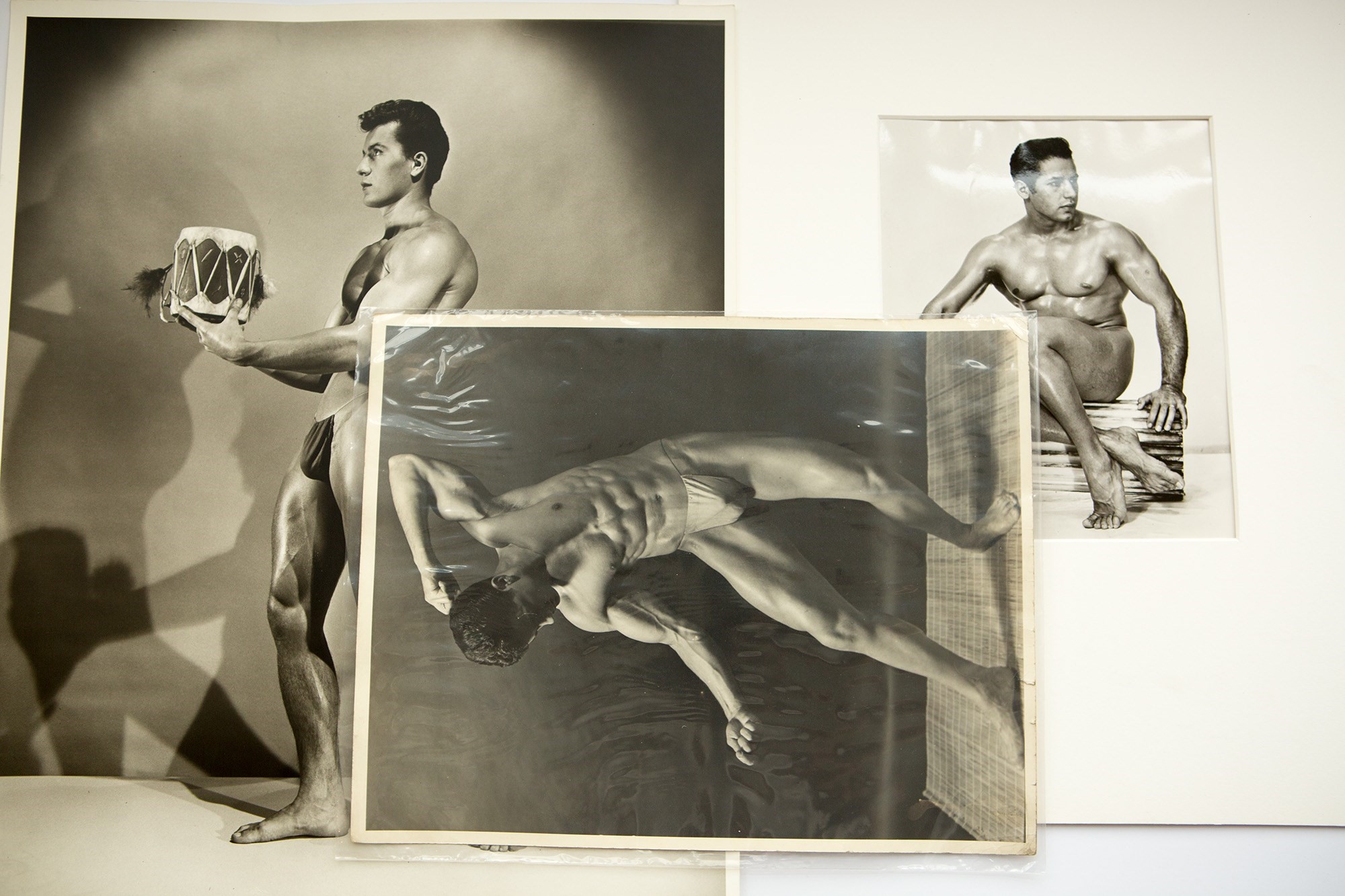

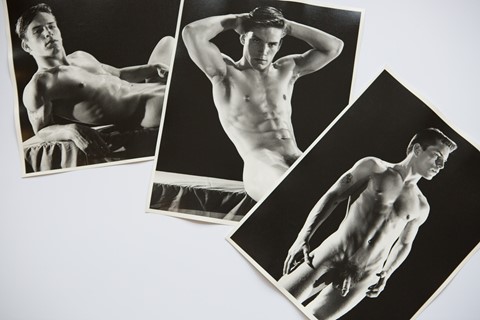

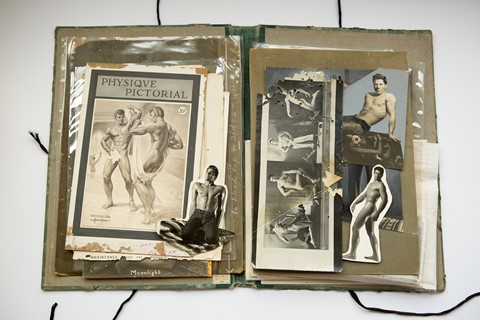

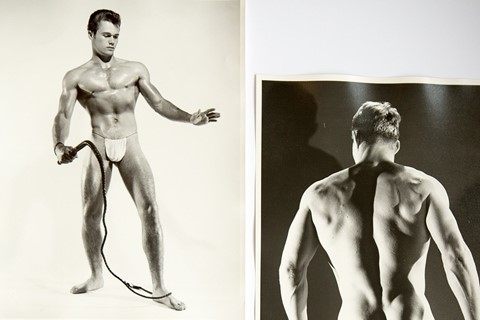

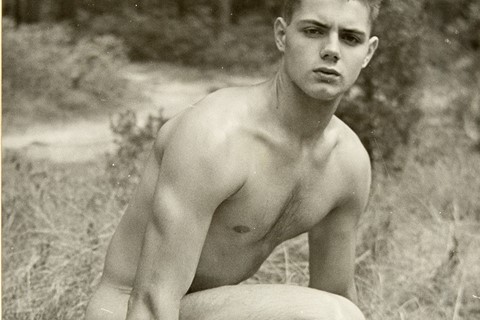

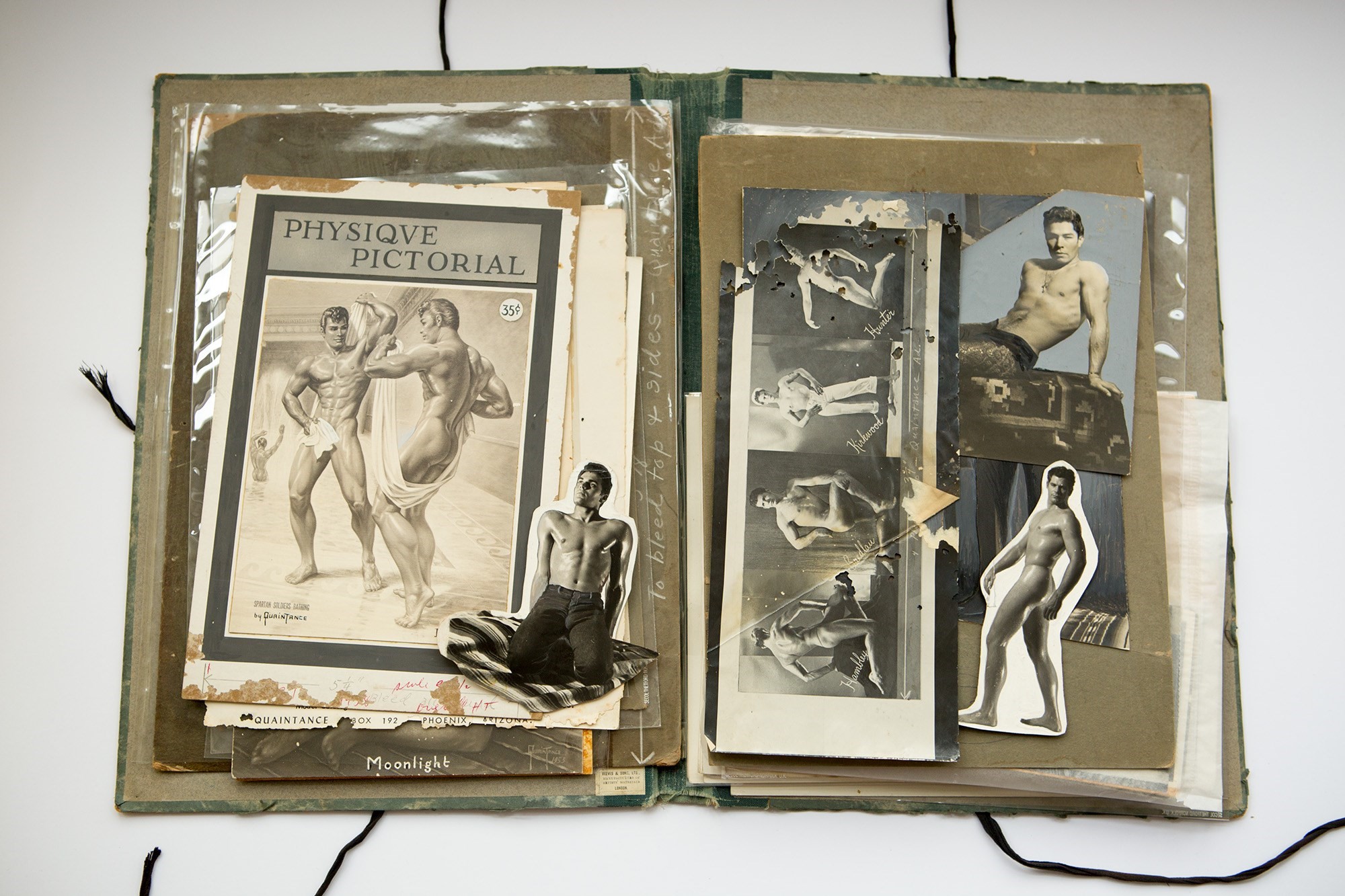

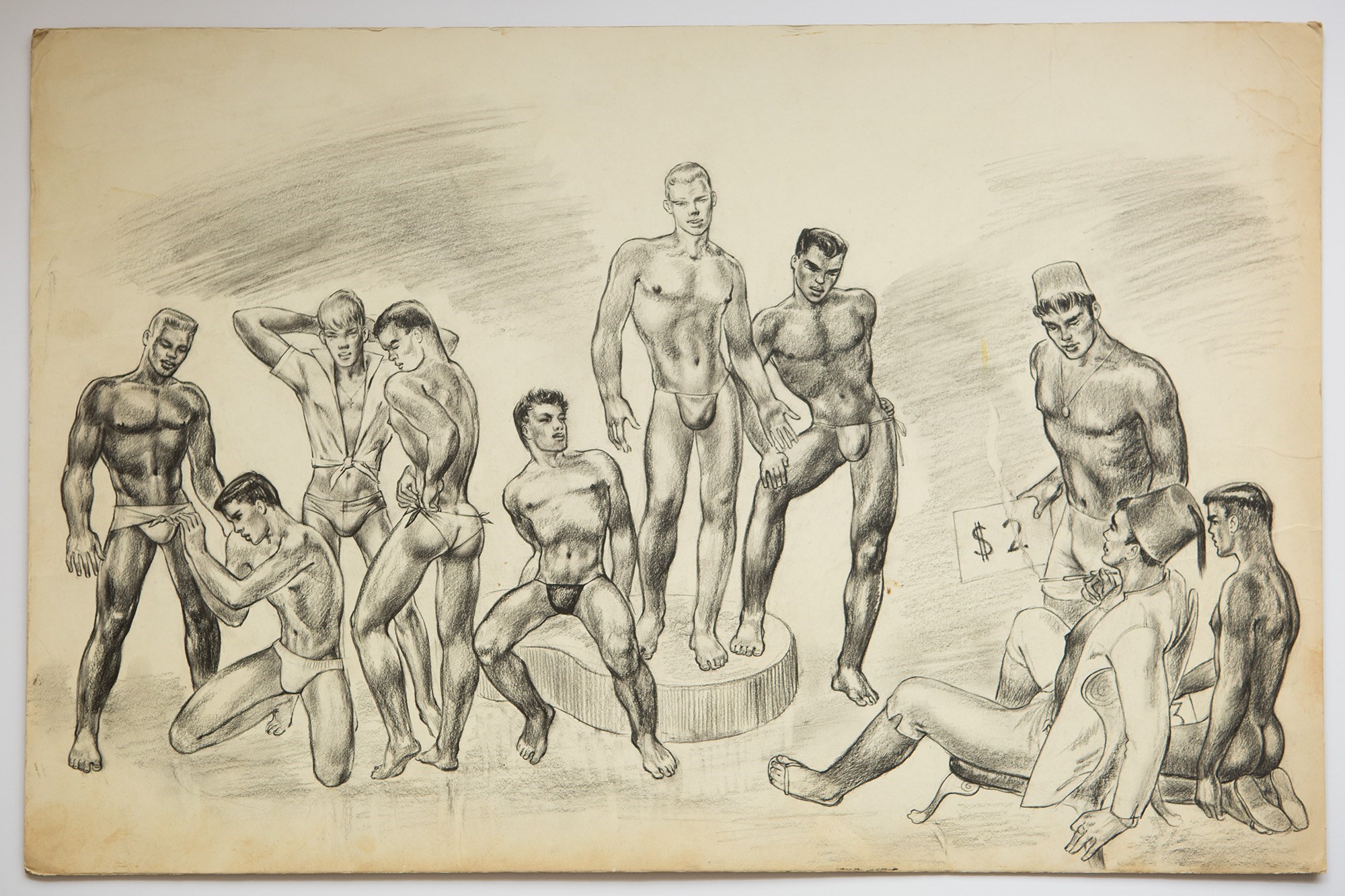

An example of this duality is the athletic masculinity that was often used for queer coding in previous eras. Physique Pictorial is an American magazine that first emerged in the conservative 1950s. To the heterosexual majority, the publication appeared to be a bodybuilding magazine which advertised various sporting products. But in reality it is a prime example of how bodybuilding culture and catalogue-style poses were used as a thinly veiled cover for homoerotic imagery. In each magazine, oiled up men would pose in very little clothing – including jockstraps, normally in classic white – and evade the charges of obscenity which came with distributing gay porn at the time. Even now, male sporting spaces like the gym locker room are highly fetishised in gay porn. In 2019, Vice UK investigated why so many gay men still go cruising at the gym, after a Virgin Active health club emailed its members saying it would be sending in undercover police to check for “inappropriate behaviour”.

When it comes to men’s underwear, developments in fit and design have often been paired with, or influenced by, particular sports and physical activities. Susanna Cordner, archive manager at London College of Fashion and assistant curator on the 2016 V&A exhibition Undressed: A Brief History of Underwear, tells me this is partly because of the close relationship between sport and underwear design, where high-tech cuts and materials are developed to aid physical activity. But it’s not just that: “I also think it’s about what’s considered acceptably aspirational in terms of men’s relationships with their bodies and with those of other men,” she says. “Sportsmen have been ready-made role models and underwear models alike – footballers like David Beckham are obviously famous for modelling underwear today, but they were predated by baseball players in the 1930s.”

The gay popularity of jockstraps in particular feeds into a tradition of queer men borrowing and reappropriating items from a mainstream masculine culture – something many have felt excluded from in the past. João Florêncio, a senior lecturer in masculinities and visual culture at the University of Exeter, tells AnOther that there are similarities between how LGBTQ+ people have reclaimed words like “queer”, which were once used as insults, and how garments like jockstraps have been reclaimed from the dominant straight culture. “It’s quite empowering because the culture that you are drawing from is oppressive – if we’re thinking about sports, for a queer person sports at school and in changing rooms were often scary,” he says. “So it’s empowering that you can find yourself able to take those very same signifiers and make them gay as hell.”

The process of gay men adopting from straight culture was famously documented in photographer Hal Fischer’s 1977 book Gay Semiotics: A Photographic Study of Visual Coding Among Homosexual Men. The book unpacks the gay archetypes of the Castro district in 1970s San Francisco in the era of civil rights icon Harvey Milk. Some of the archetypes – which included “cowboys”, “leather daddies”, “jocks”, and “basic gays” – could be traced back to classic Hollywood representations of masculinity, like Marlon Brando’s 1953 film The Wild One and Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. Fischer observed that these archetypes were often dependent on context. “Your ‘basic gay’ look, was really adopting certain masculine signifiers, like flannel shirts and jeans,” he said. “Out of context, maybe if you wore that in Billings, Montana, it wouldn’t necessarily have read as gay. That’s because these things were all adopted from mainstream culture.”

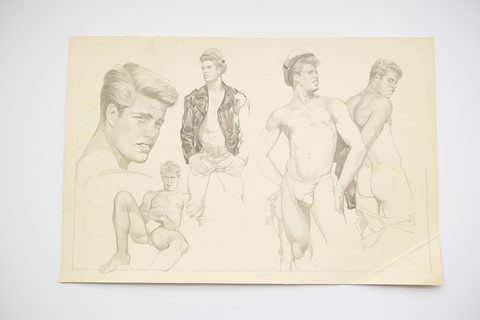

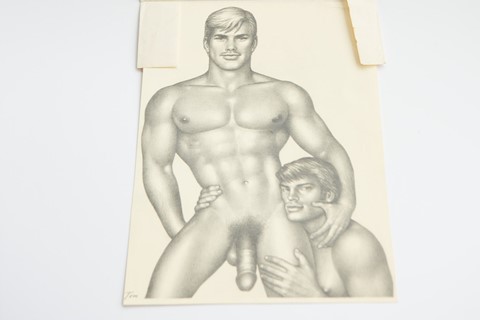

The gay leather scene is another example of this adoption process. Here, a costumic form of exaggerated masculinity – depicted in the artwork of Tom of Finland – was adopted by men who were tired of their queerness being rejected or branded feminine by mainstream male culture. Florêncio thinks that there’s something costume-like going on here. “American culture and masculinity began turning into almost like a form of drag, which could be read as gay by the people who were able to understand it,” he says. “So apparel that first came from a straight and often suppressive culture is appropriated and read as gay those who are ‘in the joke’.”

Being ‘in on the joke’, whether it’s tweeting a precise pop culture reference or re-appropriating something from straight culture that only other LGBTQ+ people will perceive as queer, feels like a highly-valued trait within metropolitan gay culture. And there’s a decades-old tradition of fashion being used this winking way, whether it’s in the pages of Physique Pictorial or the infamous “hanky code”, which was used for secretly communicating an interest in sexual activities and fetishes.

When it comes to sex, jockstraps are generally associated with bottoming, the receptive form of gay sex. This is probably because, while the front pouch accentuates the crotch, the butt is left fully exposed. There has traditionally been a stigma attached to bottoming, both from inside and outside the LGBTQ+ community. Bottoms have been stereotyped as feminine, and then subjected to femmephobia because of that perception. But there’s now a growing awareness that bottom-shaming isn’t acceptable. There’s even a genre of memes dedicated to celebrating a Very Online idea of “bottom culture” in a self-deprecating, humorous way.

The shift in attitudes towards bottoming – and the embrace of garments like jockstraps which have become associated with it – might also be connected to sexual health advancements. Men who bottom regularly are statistically more likely to contract HIV and other STIs, but the introduction of HIV prevention drugs like PrEP, and a wider awareness of facts surrounding transmission, has lessened the association between bottoming, illness and death. “In the 1970s, gay men almost flaunted it [bottoming] because it was seen as kind of manly to get fucked,” says Florêncio. “Then that went away during the Aids crisis, but now I think so many gays are just flying the bottom flag once again.”

The jockstrap seems to be having a moment right now because it’s existing at the point where several norms are being questioned. Cordner tells me that the history of underwear is littered with both subversion and conformity, particularly when it comes to gender roles. This makes underwear “ripe ground” for subversion, particularly because “our expectations about who wears what styles and categories of underwear are so set, that they have also always been there to rebel from, whether in public or privately.”

Emancipation and restriction is stitched into the very fabric of the jockstrap: in the most basic sense, it is designed to both hide and show off. But also, Cordner notes that men’s underwear has tended to be framed as more practical or functional than women’s designs. The more decorative and legibly gay designs that we are seeing now are subverting this functional norm, but also conforming to it in a situation where sex is on the cards. Similarly, the pattern of gay men adopting garments from mainstream masculine culture, such as the jockstrap, can be read as both subversive and conformist, to varying extents, depending on the context and time period. The same can be said for the flaunting of a male sexuality that places gay sex front and centre, while attaching various gendered traits to a so-called “culture” which surrounds it.