This article is taken from the Spring/Summer 2022 issue of AnOther Magazine:

Pieter Mulier seems at home at the house of Alaïa. It’s an early winter evening, dark by six, almost a year since he began as creative director. We are in the backstage area for his January 2022 show, normally the Alaïa boutique at 7 rue de Moussy, with its panels of glass and bare brick walls, gargantuan artworks just leaning against them. As you walk in from the street, you ascend a small flight of stairs, directly facing a monolithic colour-daubed canvas by the artist Christoph von Weyhe, Azzedine Alaïa’s partner. In the cabine to the left there’s a Julian Schnabel smashed-plate portrait of Alaïa that, thanks to the angle of the shattered porcelain around the mouth, appears to be staring beatifically. When the light shifts the face seems animated, alive.

Mulier is sitting at a glass-topped table between two rails of the clothes that he’s about to show. I ask him what the collection is about, a hackneyed question. “The beginning of the collection was a sense of family,” Mulier says, softly. “It’s a love song, for Azzedine. And it’s everything I find important for Azzedine. Everything he loved.” As he says this he’s flanked by body-conscious dresses, their bombastic shapes squiggling even on their hangers. There’s a bit of animal print behind him, and a full skirt in featherweight poplin, the kind Alaïa adored, but here attached to leather thigh-high boots. He’s playing with a pair of sandals that have brackets of red metal bolted on as their heels. They’re based on the work of Jean Prouvé: Alaïa was a passionate collector, a statement that understates his fervour entirely. He slept in a glass petrol station Prouvé designed in 1953, one of only three remaining. I often feared leaning back on a chair chez Alaïa, because most of them should have been in museums. Behind Mulier are shelves stacked with bangles. “Techno Nancy Cunard,” Mulier says, picking one up. It’s a polished-brass, small-scale recreation of the Alaïa Diabolo waist-cincher belt from Spring/Summer 1992. In leather aerated with punched designs resembling broderie anglaise and with serrated edges, it’s a favourite archival piece of Mulier’s. It’s one of the first he reissued, full-size, in different leather finishes, including one that resembled blown glass. In miniature, in metal, that belt-bangle looks almost industrial, a small cog for a big machine.

Mulier was an unexpected appointment to Alaïa, announced about three and a half years after the founder’s death in November 2017. He was a relative unknown outside tight-knit fashion circles, having worked as right-hand man to Raf Simons from 2002 – when he began as an intern in that designer’s company – until 2018. By that point, Mulier had been appointed creative director of Calvin Klein, alongside Simons’s chief creative officer role, but was still a low-key figure even though he took a bow with Simons at their debut Calvin Klein 205W39NYC show for Autumn/Winter 2017, and regardless of his role in Frédéric Tcheng's 2015 feature documentary Dior and I, which charted his work alongside Simons on their debut haute couture collection for the label.

That did raise Mulier’s profile, granted – and gives something of an insight into both his working processes and the inestimable importance of his innate ability to enthuse and engage a team of highly trained and, perhaps, slightly jaded technicians to make his dreams a reality, to excite the same passion in them that he feels himself. You observe Mulier working with Simons to manipulate pieces from the Dior archive, dusting off cobwebs to try to give a new relevance to the house’s storied but sometimes staid history. And you see the delicate pas de deux between Mulier’s mind and the ateliers’ hands. “Pieter, j’adore,” said Florence Chehet, the formidable première of Dior’s flou atelier, to camera. She’s blushing. And eliciting that kind of emotional reaction – joy, loyalty, devotion – is arguably more Alaïa than any curvy leather jacket or spiral-zipped knit dress.

When I first speak to Mulier, four months after he was appointed to Alaïa and two and a half weeks before his debut show for the label, he’s excited, enthused. He lights up when talking about Alaïa’s ateliers, and understandably so. They are known as some of the best in fashion – as other houses closed their haute couture operations, Azzedine Alaïa employed the best of the best, with impeccable pedigrees. His retinue of staff included seamstresses trained by Cristóbal Balenciaga and 15 former members of Yves Saint Laurent’s couture workrooms, employed after the cessation of that line in 2002. Many are still with the company today – including Alaïa’s first assistant, a shaven-headed Hiroshima-born artist and designer named Hideki Seo. Mulier only brought one collaborator with him – Frenchwoman Clémande Burgevin Blachman, who headed Calvin Klein’s home division and who is an Alaïa obsessive herself.

In June 2021, over one of those glitchy Zoom connections that have become the defining audio of our time, Mulier’s reverence for the craft of the Alaïa ateliers – and their point of view – is paramount. “I ask the two heads of the atelier, when we see pieces, ‘Is it Alaïa?’ Always. At the beginning they didn’t answer me. I said, ‘I really respect you, I really want to know. Is it Alaïa?’ In three weeks they started to answer.” He smiles. “They’ve been here 25 years, they know.” And the outcome? “Last week, when we did the selection for the runway and the showroom, they were both crying. That’s even more important than the collection.” He takes a breath. “The ateliers are alive again. It’s a human thing.” It’s clear why he was chosen.

Jump forward to this year, back inside the bare brick walls of the Alaïa backstage-boutique space. The January 2022 show marked Mulier’s second catwalk collection for Alaïa, but his fourth overall. There was a swim capsule but, first of all, a pre-emptive series of pieces, unveiled in a digital campaign photographed by Paolo Roversi, an old friend of Alaïa’s and a new collaborator for Mulier, as a kind of preview before his first show in July 2021. They consist of what the house calls archetypes but what Mulier, privately, calls Alaïa icons – and they’re the rare fashion pieces today that truly deserve that often-hyperbolic moniker. There’s that Diabolo belt, alongside leggings and a coeur croisé halter top, a flared skirt, and another laced tight down the thigh and constructed of horizontal strips of fabric, from Alaïa’s famous 1986 Bandelette collection. “I remade each icon in a reflective yarn from Japan,” Mulier says. “It’s all the shapes that I think are diehard. It sets the tone.” As shot by Roversi, they became silhouettes of pure light, almost ethereal. Maybe spiritual.

It’s difficult not to feel the spirit of Alaïa in the house he built, because it isn’t just a house in that fashion sense. Azzedine Alaïa’s idiosyncratic bedroom is perched on top of the building; von Weyhe, whose relationship began with the designer in 1959, still sleeps a few hundred feet from where Mulier and I are talking, in an apartment in the warren-like complex. Monsieur Alaïa famously hosted friends in the space, with multiple bedrooms for them to stay in, and held dinner parties and lunches around his kitchen table for an eye-popping mix of his atelier workers, artists, writers and general devotees. I once failed to recognise Monica Bellucci, seated opposite me. Because who has Monica Bellucci in their kitchen?

Maison Alaïa was always more home than house – Alaïa’s first fashion shows, in the early 1980s, were held in his own tiny flat on rue de Bellechasse on Paris’s Rive Gauche, audiences crammed into the living room, some sitting on the floor, Alaïa pressing clothes in the kitchen. The house in the Marais is much bigger – 750,000 square feet, or thereabouts. Alaïa moved there in about 1988, and began showing his collections there the following year. Yet the man himself always seemed omnipresent – startled shoppers often caught a glimpse of him crossing the boutique floor, as his studio was just overhead. Physical then, his presence is ideological now, almost five years after he died.

Mulier doesn’t shy away from the legacy of Alaïa, one many would find overwhelming or overpowering. Indeed he seemed giddy at the thought of it when we first met at the house last year, bubbling over with references to Alaïa’s greatest hits – which were also present, all around. Burgevin Blachman was darting about wearing a leopard intarsia skirt, from Alaïa’s Autumn/Winter 1991 collection. It would be tempting to say that Mulier’s collection featured a checklist of Alaïa-isms – but that would be lazy, which Mulier isn’t. What it felt like was an instinctive, even gut reaction to the potential sucker punch of taking up one of the most formidable mantles in modern fashion. Mulier went with what he loved. “I played around with what I thought was Alaïa,” he told me, just before that first catwalk collection was presented. “The base was in the Eighties, that’s when he began to build. The sense, the essence.” It was as direct as the curvy corset-belts, body-defining knits and leopard prints, and as subtle as a meandering fagoted seam defining the erogenous zones of the bust and waist on brief dresses and bodysuits.

“Full-on” is how Mulier described that first collection, a recalibration of those Alaïa greatest hits, reimagined for a new audience. “I want to bring a sexuality back,” he added. “Alaïa is the only house that can do sexuality without being vulgar. Here in the atelier, from the moment they do something sensual – nearly explicitly sexual – it’s just beauty. That’s the strength of this house.” He even switched the labels back – in the 1980s and 1990s they were bold black on white typeface. “It’s a small thing, but it’s an important thing,” he says. “You know, most of them were stitched all the way around. So you could never take it out.” He laughs. “Very Azzedine.” Mulier also chose to make his debut outside the boutique on the aforementioned rue de Moussy, a doubly loaded act. Firstly, it recalled a famous Arthur Elgort image of statuesque Alaïa models in the street after one of his shows in 1986, and an Ellen von Unwerth film that includes scenes of Linda Evangelista and Christy Turlington cavorting around the Marais after another in 1990. Those images loaned a reality to Alaïa’s fantasies – and the same to Mulier’s. It was also, Mulier says, about humility and respect. “You must respect Alaïa,” he says. Mulier smiles a great deal, but he isn’t smiling now.

If that first collection was something of a mark of that respect, it was also a communiqué of Mulier’s intent as well as a palimpsest demonstrating his knowledge of Alaïa’s past. Mulier – like Azzedine Alaïa – is a passionate collector of vintage clothing. He and his partner, the designer Matthieu Blazy, who is now creative director of Bottega Veneta, have a vast archive of vintage pieces at their home in Antwerp, spanning from Twenties Lanvin through more obscure names such as Norman Norell to modern masters like Martin Margiela. Since his appointment last year, Mulier has – understandably – been buying vintage Alaïa pieces in a frenzy, turning them inside out, examining their cut and construction. He’s especially drawn, he says, to early Eighties pieces, which are the rarest.

There’s a magic in objects that images often cannot convey – especially in work like that of Alaïa, devised as three-dimensional pieces with a sculptural quality. Moreover, many contain tricks and traits that can only really be appreciated in the physical handling – skirts tugged into position by belts, dresses whose surfaces are composed of a multitude of interlocked pattern pieces, giving them a unique physical tension, like stroking your hands over a living body, feeling the give and take of muscle and skin. Alaïa once described one of those dresses, intricately seamed in wool jersey, as like a racehorse. And he certainly believed in the magic of objects – his quietly amassed archive, held by the foundation established after his death, is now regarded as probably the most significant private collection of fashion in the world. It includes pieces by Balenciaga and Charles James, Madeleine Vionnet and the Hollywood costume designer Gilbert Adrian, all of which influenced his own designs. The archive holds more than 22,000 examples of those, too.

Many designers accumulate fashion collections – vintage pieces are valuable reference points, after all. But the manner in which both Mulier and Alaïa collected has a certain kinship – a value given to pieces from the past, an innate appreciation of fashion, a love of and fixation with craft, and an urge to protect. It’s miles from the slavish copying of archival pieces, and luckily light years from the hopefully apocryphal tales of fashion designers torching vintage garments to hide just how closely they were ‘inspired’. Alaïa once told me a story of a rich family he knew, former clients of Vionnet. They lived next door to a convent and, at the end of every season, gave their cast-off couture to the nuns to chop up and sew into habits. Alaïa looked aghast when relaying that story. That idea of cherishing fashion, the value of its history, isn’t something everyone has.

There are other connections between the two. How about the fact they’re both kind of outsiders in Paris? Alaïa was born in Tunisia, coming to Paris in 1957, Mulier is Belgian, although his accent is soft. Both began quietly, in the shadows – and, actually, worked in some of the same ateliers. Alaïa’s career began at Christian Dior – although he was only employed for four days because of issues with immigration papers. Mulier was there for three years, from 2012 to 2015, alongside Raf Simons, who was then the artistic director of womenswear. Alaïa, incidentally, attended that first couture show, and all the ones that followed. It was Simons who first encouraged Mulier, as a student, to pursue fashion instead of his intended vocation of architecture, in which he originally trained at the Institut Saint-Luc in Brussels after a brief foray into law. Another parallel: Alaïa studied sculpture, not fashion, yet he referred to himself as a bâtisseur, a builder, although his clothes were neither stiff nor heavy. Indeed, Alaïa’s breakthrough in 1980 was to create a collection entirely in leather, studded with eyelets. He gave the hitherto unyielding material a new softness and suppleness, pulling it tight around the body. The clothing collection was originally designed for the shoe manufacturer Charles Jourdan in 1979 – the company freaked out at the strident, powerful sexuality of his garments and nixed the collection, but Alaïa presented it under his own name, his first ready-to-wear collection.

Sex is something Mulier is interested in – who isn’t? And sex was Alaïa’s leitmotif. “The iconic part, for me, was from 1980 to 1994 – the heyday,” Mulier says. “It wasn’t lady – although I do love that aspect. But that is when the Alaïa revolution really happens. Timeless simplicity, sensuality and sexuality. That’s the most important.” His first collection showed both sides of sexuality: a python top and skirt, composed of snakeskin, were laced tight, gaps showing the flesh underneath. Another floor-length dress covered a model entirely, a hood smothering her scalp, gloves her hands, but the dress clinging close, which reminded me of those violated Vionnet nun’s habits. In his second collection, there were vestal virgin shirt dresses that were cocooned in the back, drawn in at the knee and kicked out into a pooling mermaid skirt.

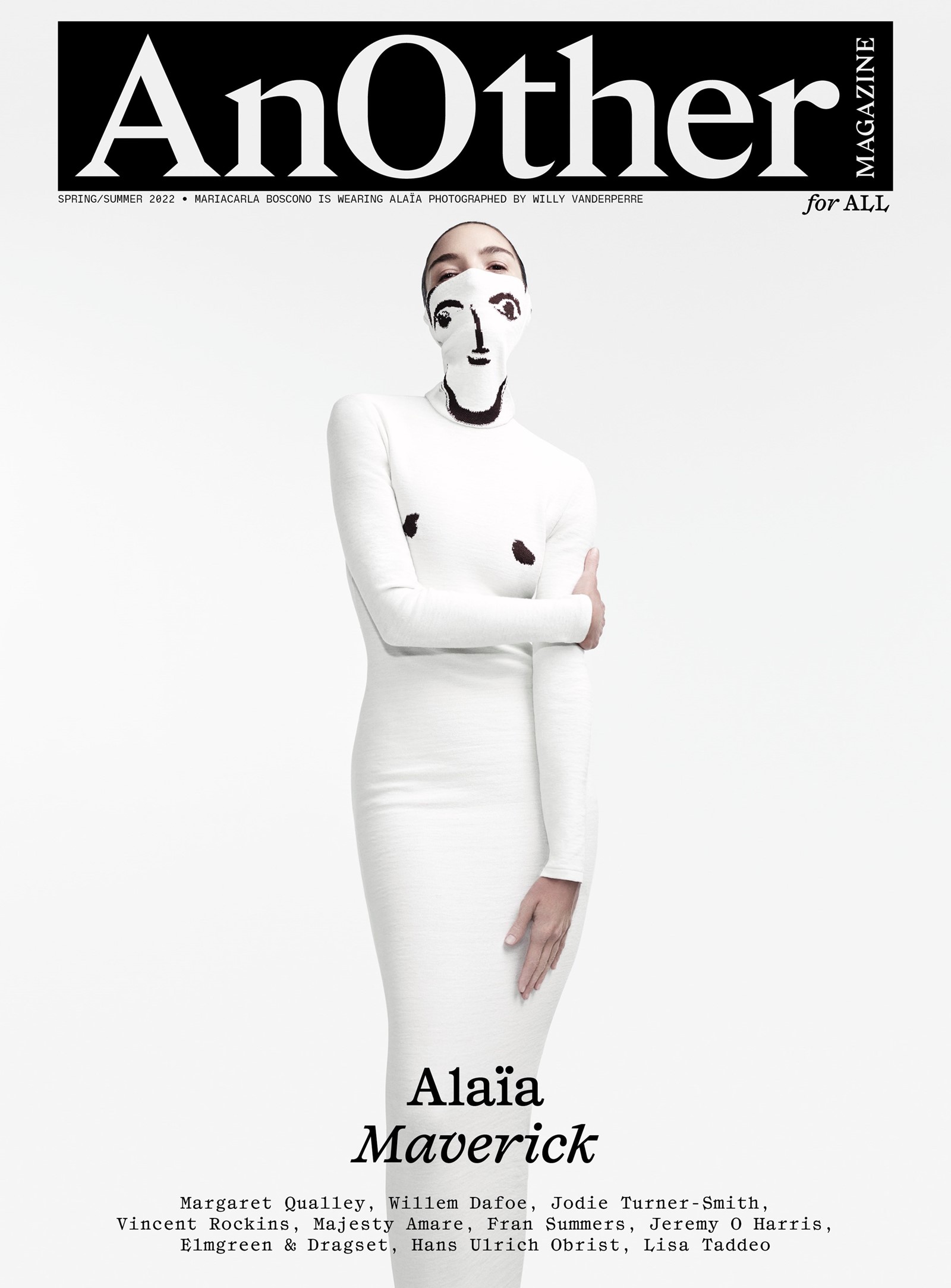

If the first show was, by necessity, demonstrating Mulier’s agility with and understanding of Alaïa’s codes and, indeed, his respect – “A beautiful word,” he says – the second seemed like he was relaxing, stretching a little. “Clients are coming. Couture is working extremely well. I feel confident,” he says. While Mulier doesn’t want to impose his vision on Alaïa, he hastens to add that Alaïa cannot be purely referential. “Don’t change it, but push it,” he says. “Bit by bit.” It embraced more of Mulier’s own loves. The soundtrack was classical music – “I was raised with classical music,” Mulier says, commenting that it reminded him of his mother. There is a sequence of dresses created in close collaboration with the Picasso Administration that marry Alaïa’s body-clinging knit with motifs drawn from Pablo Picasso’s sculptural porcelain female figurines of the late 1940s, called tanagras after their reference to antecedents from the Hellenistic period. “An ode to Azzedine, who was the greatest sculptor of fashion,” Mulier says. “The idea behind it is to put Azzedine – as the greatest sculptor of fashion – with the greatest sculptor in the world.” He smiles. “And also, everybody talks about collaboration … but you cannot go higher than Picasso.” He shrugs.

There’s also history there: Mulier was able to call Claude Ruiz-Picasso, son of the artist and the painter Françoise Gilot, and one of the heads of the Picasso Administration, to ask for permission. “We worked together at Jil,” he says. That is of course Jil Sander, where Raf Simons and Mulier collaborated with the administration in 2011 on a series of knits inspired by ceramics. “There’s some Raf in there too,” Mulier allows, of these dresses. “It’s a nod to Raf, what he means in my career.” Simons is, of course, part of Mulier’s community – his family, even. After more than 15 years working side by side, the two are still close – they speak constantly, and Simons was a prominent front-row presence at Mulier’s debut. For this second show, he was referenced in a letter addressed to Azzedine that Mulier placed on each seat: “Raf, who taught me the love of art and how to mix it within my creations.”

“The idea behind it is to put Azzedine – as the greatest sculptor of fashion – with the greatest sculptor in the world … everybody talks about collaboration … but you cannot go higher than Picasso” – Pieter Mulier

Their continued synergy is interesting: Mulier shows me a dress where fullness is created by nylon crin (or horsehair) knitted into the structure itself. “They normally apply it after,” Mulier says. “This is the first time.” A week before, Simons had enthused to me about sweaters in the Autumn/Winter 2022 men’s collection he had created alongside Miuccia Prada. Their swaggering shape was created by nylon thread similarly knitted into the shoulder line. “It’s actually all people, on a personal level, that gave me a chance,” Mulier continues. “It’s the house of Alaïa, I cannot talk of Azzedine like that” – he and Mulier never met. “But still, yes – it’s his house. It’s Raf, who still plays such an important role in my life. And sculpting and fashion and architecture is the concept. It’s about how to sculpt beauty.” He stops again, smiles. “Sounds very pretentious, and I don’t mean it pretentiously at all.”

It is interesting that instinct leads Mulier back, somehow, to Azzedine Alaïa, who referenced ancient Greece also, in his artfully draped and bound dresses; he adored the Musée Picasso, which opened in the Marais a few years before Alaïa moved to the rue de Moussy. And the Picasso family were intimates. “He was very close to Claude Picasso,” Mulier says. “We called him, and he said yes to the collaboration in a minute.” Then his voice rises. “Because he used to come here and sit next to Azzedine when he was pattern-making.” The Picasso Administration was included in every step – the resulting dresses, a half-dozen, combine intarsia knit with hand embroidery, and will be limited edition. “They’re very involved, and that’s what I like,” Mulier says. “It’s this sense of community – almost like a Bauhaus.”

Mulier jumps up. He wants to show me the space where the show will be held, an enormous double-height atrium with a vaulted glass roof. “We are showing in Azzedine’s heart,” he says. “I always call it the cathedral.” The Alaïa complex is so big, it straddles an entire city block, and technically the entrance to this space is at 18 rue de la Verrerie, through a pretty courtyard with a giant hammered-bronze female breast incongruously plonked in the centre. It’s a 1966 sculpture by the French artist César – a friend of Alaïa’s, of course – and its full title is Le Sein d’Hélène Rochas, modelled after the embonpoint of that fixture of French high society, a doyenne of haute couture and artist’s muse.

The cathedral betrays the origins of the Alaïa building – built in the 19th century, it was latterly a warehouse for the Bazar de l’Hôtel de Ville department store around the corner on the rue de Rivoli, and formerly a factory that, during its time, created clocks and mattresses. That feels ironic: Alaïa was rarely on time – during the 1980s, his shows not only famously ran hours late, but were presented weeks after the rest of the fashion industry had wrapped up their seasonal presentations – and given his passion for his work, he didn’t really sleep much. Alaïa himself presented collections here from 1989 onwards – unless, perhaps, he decided to cancel a show because the clothes weren’t up to his exacting standards, or because he didn’t want to force his beloved dogs out of the space. “In its present, unfinished state, a chill rain dripped through the cracks, showering press and buyers during the 1½-hour wait,” wrote the Los Angeles Times, of Alaïa’s first show at rue de la Verrerie in May 1989. “The models got wet, too.” The models at Mulier’s debut got a little wet also – Paris decided July 2021 was a time for rain.

It brings a wry smile to my face that, to many eyes, the Alaïa headquarters still doesn’t seem finished: when I walk through in January, that exposition hall is a building site. Although, credit where due, that was because the space is also used by the Fondation Azzedine Alaïa to stage exhibitions. They were taking one down, juxtaposing Azzedine Alaïa’s clothes with those of Cristóbal Balenciaga, to allow Mulier to use the place for his sophomore show. Showing there “was my dream, in the beginning”, he says. “But I’m happy I didn’t do it the first time.” Mulier enthuses about a wrought-iron staircase off to one side, normally boxed in and rarely revealed to public view, and by a series of enormous maps painted onto raw plaster walls, again usually hidden. The vaulted ceiling had also been shrouded in cloth that blocked out the sky, Mulier said, for almost 20 years. Stripping Alaïa back to its bones – its foundations – excites him.

What do those constitute? This collection, it seems – it’s the unexpected, the extreme. “It’s big fashion this time,” Mulier says. “It’s about shoulders, about volume. It’s about proportion and sculpting. It’s very simple, really.” There are knitted bodysuits in wool, in black or nude – Alaïa offering nine shades of ‘nude’, reflecting the inclusivity that was one hallmark of its namesake. “You’ll buy it in a box – and it looks like a Sarah Lucas!” Mulier laughs. Sculpture again, I guess. “But on the body it’s sublime.” He sounds just like Simons when he says that word. As with Azzedine Alaïa’s own collections, conventional seasons are eschewed – Alaïa has named them Winter/Spring and Summer/Autumn, reflecting when clothes will actually arrive in stores, and chooses to show them just outside the official haute couture weeks. The collections themselves include a mix of couture pieces and ready-to-wear, which Alaïa himself initiated. “The beauty here is that even ready-to-wear has a couture feeling, the construction, the finishing,” Mulier says. “It’s not important to put it in a category.” The finale of the show, entirely haute couture, features ball gowns made in calfskin and Japanese velvets – all the fabrics, Mulier says, are made especially for Alaïa, including specially treated leathers.

Some details are more esoteric: several dresses, and those aforementioned bodysuits, are held in place with moulded metal frames around a deep, undulating décolletage. Reflecting Mulier’s love of community spirit, they were shaped by the husband of one of Alaïa’s premières. “He makes staircases,” Mulier says. “She’d go home in the evening and send videos of him manipulating it.” That neckline is an echo of a dress Alaïa called the Carla, after Carla Sozzani. It wasn’t because she wore it: in 1987 she put the dress on the cover of Italian Elle – she was then its editor – shot by Roversi. The publication was devoted to championing Italian fashion only, and Sozzani was promptly fired. I love that story.

Azzedine Alaïa was a storyteller, a raconteur par excellence. Those stories have outlived him. Mulier is delighted by one account of him spending an exorbitant amount on a coat by Paul Poiret – an inspiration for bloused backs on dresses and coats, with a 1911 feel, caught in low around the thigh. They’re influenced by a coat from 1985, which not only shapes the gently curved tailoring but also appears in the show. It nods to another famous story, of Alaïa creating a coat for the actor Greta Garbo in the 1970s. By then Garbo had become a reclusive figure. “They told me she was waiting outside with Cécile de Rothschild. I said, ‘Sure, who else?’” Alaïa recalled, with his typical humour, in 1990. He made her a dark blue cashmere coat – “Big, bigger, biggest! And a huge collar to hide.” He kept the patterns until the day he died.

The Garbo collar inspired Mulier to pull turtlenecks over the mouths of his models, an echo of her mystique. Edie Campbell, daughter of Sophie Hicks, had a Picasso pulled over hers – Hicks was a friend of Alaïa, and is currently redesigning the brand’s boutiques (new ones are set to open in New York and Shanghai). “I think he loved Garbo because cinema in Egypt and in Tunisia when Azzedine was growing up was a copy of that. He was obsessed with Hollywood, and the Egyptian copies,” Mulier says. “I asked Christoph [von Weyhe] and he agreed. Christoph told me the stories of Garbo, because he was there. He fitted the coat and everything. He said it was such a big moment because Azzedine was obsessed with her. Obsessed.” He seems obsessed too. “Can you imagine,” he knocks loudly on the glass table. “Garbo?!” Mulier’s infectious obsession, it seems, is with Azzedine Alaïa – the man, his myths.

Mulier’s Alaïa show takes place in the “cathedral”, atop a polished black lacquer floor that reflects the night sky. The moulded metal necklines make dresses appear suspended, magically, around the body; the skirts buttoned to boots seem to be hovering; and the models, walking on platform shoes with Plexiglas heels, look like they’re floating a few inches above the ground. Four days later the space has been transformed to all white, for an exhibition of archival Alaïa clothing. Fittingly, after the second show of Alaïa after Alaïa, this is titled Alaïa Afore Alaïa, and looks at the made-to-measure clothes created for his private clientele. There’s another Garbo coat – she was a repeat customer – but it isn’t navy blue. An exhibition-goer said the space looked “heavenly”, and it did.

Mulier is calm after the storm. I ask him what he wants to convey with his work for Alaïa, and he takes a moment. “Emotion,” he says, and his voice cracks a little. “I hope that comes through, that emotion. And I hope that emotion will be the same in the people who see it. It’s driven by emotion. It needs to make the heart beat. If it doesn’t make your heart beat … ” He pauses. “I mean, we’re at Alaïa.”

Hair: Duffy at Streeters. Make-up: Karin Westerlund at Artlist using DR BARBARA STURM. Model: Mariacarla Boscono at Women Management. Casting: Ashley Brokaw. Manicure: Eden Tonda. Digital tech: Henri Coutant. Lighting: Romain Dubus. Photographic assistant: Corentin Thévenet. Styling assistants: Niccolo Torelli, Ewa Kluczenko and Kevin Grosjean. Hair assistant: Lukas Tralmer. Make-up assistant: Noa Yehonatan. Producer to Willy Vanderperre: Lieze Rubbrecht. Production: One Thirty-Eight Productions. Producer: Ashleigh Hayward. Production assistants: Arthur Debriffe, Félix Biton and Julien Fernandes. On-set retoucher: Stéphane Virlogeux

This article appears in the Spring/Summer 2022 issue of AnOther Magazine, which is on sale here.