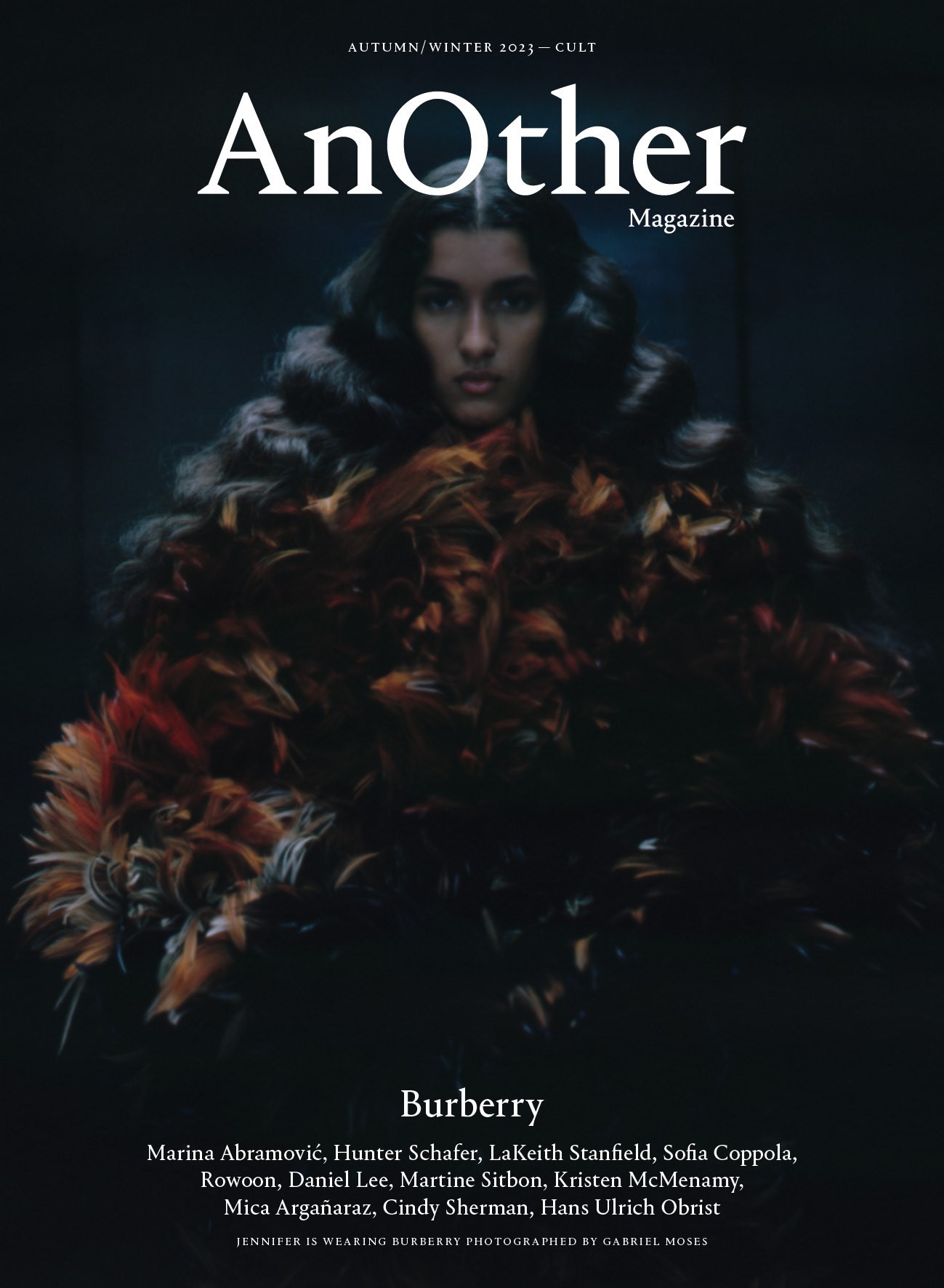

This article is taken from the Autumn/Winter 2023 issue of AnOther Magazine:

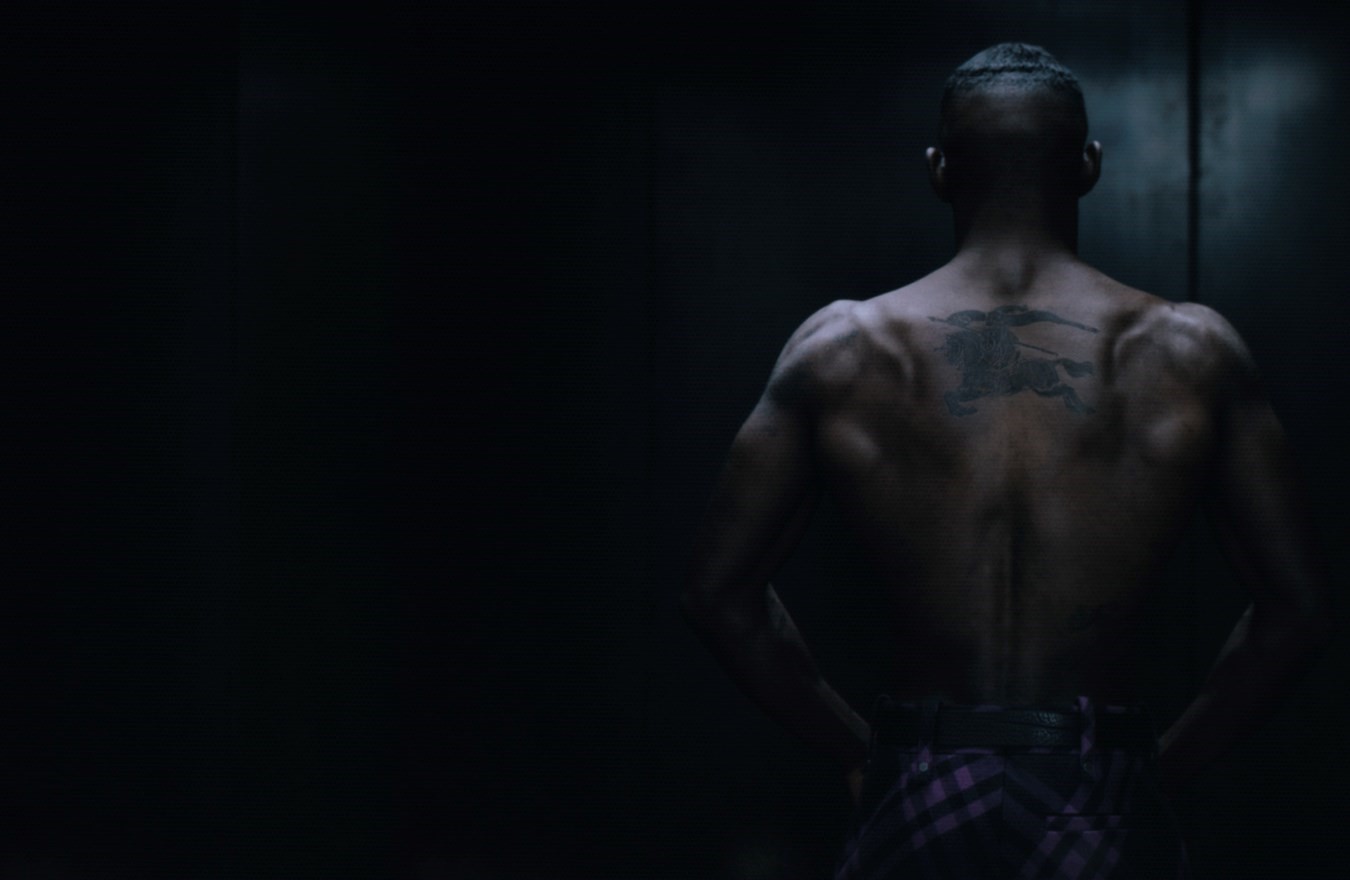

Horseferry House has been the home of Burberry since 2009: a 160,000 square foot 1930s red-brick office building, with a former life as government offices – a grand institution, in Her Majesty’s service – it rises from behind an imposing lower façade of raindrop-pocked beige sandstone. That is almost the exact same shade as the gabardine Burberry uses to craft its classic trench coat, a garment so central to the company’s repute – not to mention its country of origin’s permanently rain-soaked identity – many still colloquially call it a “Burberry”. Inside Burberry HQ, the mood switches, though: reconfigured from boxy civil service cubicles to open-plan modernity, the space is today hung with vast panels of white stamped with vibrant cobalt, a shade introduced by Burberry’s new chief creative officer, Daniel Lee, when he joined the company in October last year. He has since named it “Knight” blue – a play on royal blue, the colour was found in the archive. Almost half a century on and, today, Knight blue etches out a horse bearing a jousting figure in medieval armour, a device famous and familiar, especially to the British, from the labels of trench coats old and new hanging in wardrobes for decades. Bearing a pennant marked “Prorsum” – the Latin word for forwards – the Equestrian Knight Design (EKD) has been Burberry’s insignia since 1901. Here and now, it is not only recoloured, but its meaning is reconsidered, much as Lee is reconsidering Burberry top to bottom, seam by seam, from the outside in.

“In my first days at the brand I looked into the archive,” he says. He has much to say about Burberry in words, though more through the work he is creating. “Burberry is such an evocative name and I had my own associations with things. For me the knight was a powerful symbol of the brand. I don’t know if we consciously started with the branding. It was more of a wipe-the-slate-clean approach, more about bringing Burberry back to somewhere I felt familiar with.”

In many ways, Lee, who is 37, is the ultimate 21st-century designer. It wasn’t so very long ago that the word “branding” was frowned upon. But: “I love smart branding,” he says. In 2018 Burberry’s then powers that be got rid of any horsiness; they also renamed Burberry – traditionally, simply a company, then outfitter – a “house”. Lee, though, speaks a different language: of product, not couture (it’s true that without the haute it doesn’t have quite the same ring to it), of quality as well as luxury, of signifiers and meaning more than trends and elevation, of democracy not elitism, and, most often, of Britishness in all its incarnations: there are so many of those.

Perhaps in this context, they begin with notions of creativity: the British reputation for presiding among the world’s most respected fine art and fashion educations. Hand in hand with that goes a wildly individual sense of style that runs the gamut between ceremonial dress, hunting, shooting and fishing and the highly specific wardrobe codes of subculture – mods, rockers, skinheads, punks, new romantics, casuals. More broadly, modern Britain stands for (we make a list between us): a love of football and rugby, of the Royal Opera House and Trafalgar Square, of rolling hills and fabric mills, of club culture and Theatreland, of EastEnders and Oasis. In less than a year, Lee’s Burberry has referenced or been directly associated with most, if not all, of those things.

Fittingly, given the times we live in and the reach of his creative vision, Lee’s first communication after arriving at Burberry was a campaign featuring “classic product,” Lee says. “Obviously, a brand today has to communicate prolifically – outerwear that transcends a seasonal approach. We couldn’t wait from October, when I started, until the first show in February with nothing to say.” Having redesigned and coloured the Burberry logo and EKD, Lee employed the services of his long-time collaborator the photographer Tyrone Lebon, and shot portraits of John Glacier, Jun Ji-hyun, Lennon Gallagher, Liberty Ross, Pooja Mor, Raheem Sterling, Shygirl, Skepta and Vanessa Redgrave – quite a coup – against a backdrop of London landmarks including Albert Bridge, Nelson’s Column and the Houses of Parliament, under a dark sky and, inevitably, torrential rain. More British motifs – foxes, corgis – and water references: ducks, swans, umbrellas and, of course, the water-resistant Burberry trench coat itself. The narrative was clear, both loaded with symbolism and accessible to everyone and anyone. And that was the point.

“With a brand on this scale you can’t be niche any more,” Lee says. “You’re appealing to a wider audience and I like that very much. It is important to me that Burberry is accessible, relatable, understandable. Burberry has a history of dressing everyone from the royal family and the [late] Queen to football supporters and everyone in between.”

Founded by Thomas Burberry in 1856, Burberry is also among the oldest brands in the fashion business – it’s younger than Hermès but older than Chanel and Lanvin; younger than Louis Vuitton, but older than its monogram. Embrace Burberry’s history and, with that, the history of the United Kingdom, and move it forwards – prorsum. Welcome the cliché and take it somewhere else – somewhere new.

“Yes, the main aim is to celebrate British identity because that’s the thing that sets us apart from all the other key players,” Lee says of his work at Burberry to date. “So how to interpret and decode notions of Britishness, what it means to be British today? Among the key characteristics of Britishness are the humour and the wit, the ability to laugh at oneself – so for the first communication and the imagery we put out for that, and then for the first collection too, that’s where Tyrone and I started. Then it was about matching the celebrity of the places and the cast with the familiarity of the brand. We took the trench coat, which is Burberry’s most iconic product, the product that’s been in the store the longest, and used that as a framework. We put the coat and the check baseball cap on different British people, everyone from John Glacier to Vanessa Redgrave, from a new musician to a great actor. John Glacier kindly also made the soundtrack for the campaign. For me, everyone we cast represents a genuine and individual talent, a real substance. You could almost categorise them all as national treasures. They are people that export and communicate Britishness to the rest of the world.”

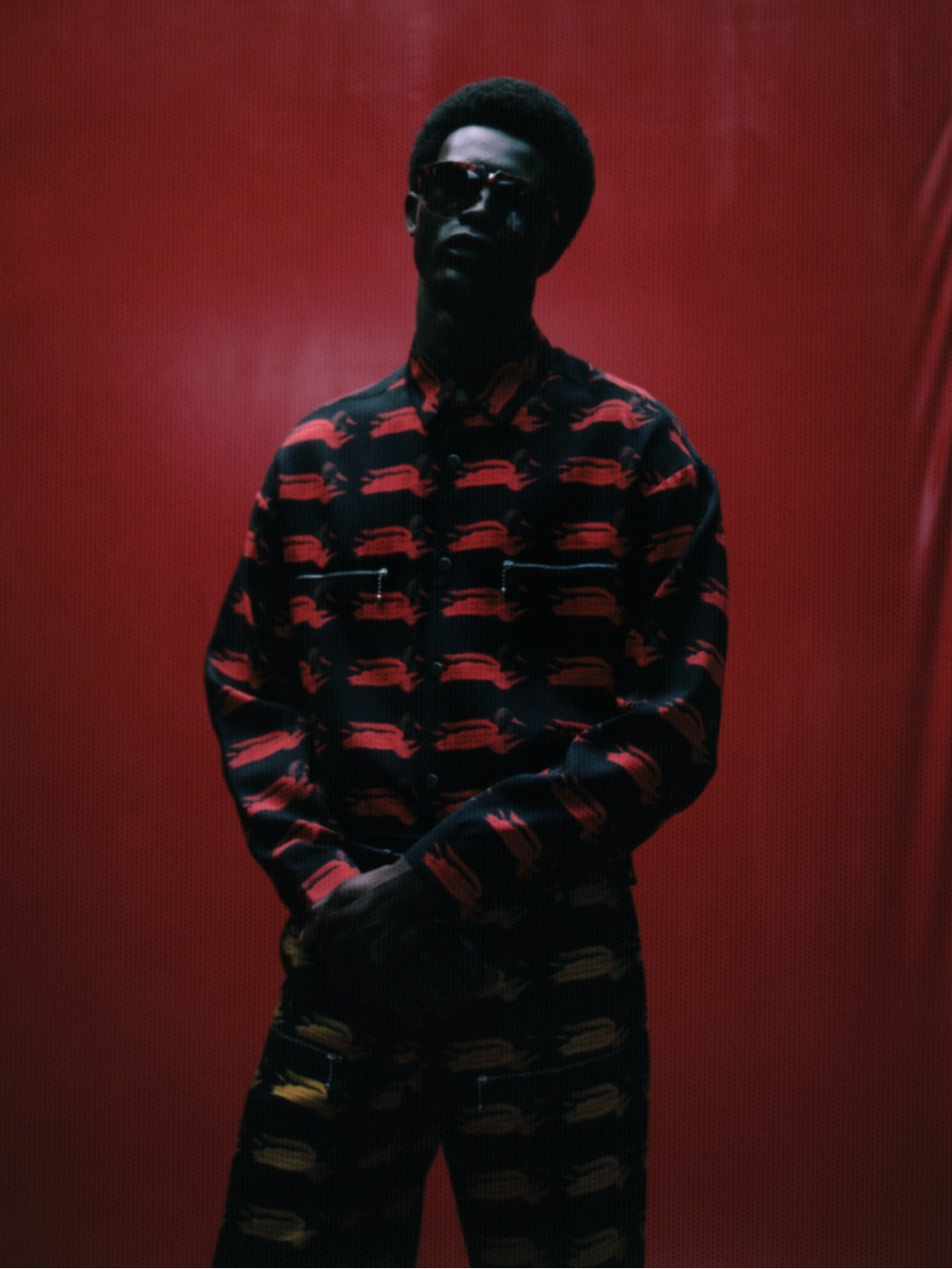

Less than a month later, the designer’s first show amplified a sense of modern Britain further still, by that point – and this time obviously – with clothes of Lee’s own design. It was staged in a cavernous tent in southeast London, with Georgia May and Bianca Jagger, Rosie Huntington-Whiteley and Jason Statham, Stormzy, Kano, Sheila Atim, Naomi Campbell, Jodie Comer and Naomi Ackie all sitting in the front row. Liam Gallagher’s children Gene Gallagher and Molly Moorish Gallagher were there too, watching their brother, Lennon, on the runway. Cool Britannia past, present and future, then. Hot water bottles clad in wool check and matching blankets were on the seats for all guests, coloured grey and black or white and Knight blue: Burberry glamping, that being a peculiarly British lifestyle concept if ever there were one. If Lee’s first campaign had the Burberry trench coat at its heart, so too did this collection – oversized with a faux-shearling trim alongside reiterations of archive designs, like the original puttee wraparound collars, found on a motoring coat from the early 1900s.

Check – it was everywhere – migrated from the inside to the outside of garments, in joyful shades, loud and proud. In 2002, Burberry famously attempted to distance itself from that pattern when the former EastEnders star Danniella Westbrook and her baby daughter were photographed in it head-to-toe, including stroller. It was “chavtastic”, The Sun said. And Burberry set about designing its way out of that with a high-end line called Prorsum, notable for the check’s absence. Times have changed: Lee is interested in the universal appeal of the check. “I think it’s beautiful,” he says. “We were also thinking about check in broader terms, celebrating the archive check, of course, but branching out from that and exploring new checks, and definitely moving on from the very beige iteration. You can take it to so many places, playing with scale, playing with colour, turning it on the bias. All of those things give it a new life. It’s familiar but new at the same time. Burberry is so big, so much a part of our culture, that the ebb and flow around it shifts alongside much broader cultural concerns.”

Lee is by no means the only designer to have appropriated and re-appropriated that check, sometimes in the most unexpected ways. In 2000, the New York-based underground designer Miguel Adrover made a garment of outstanding resonance out of a Burberry trench coat, turning it inside out so the check was visible on the surface. Back then, Burberry threatened to sue him: it’s wiser today. That trench is now part of the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

For Lee’s Burberry, the great British outdoors is a preoccupation too; the outerwear upon which Thomas Burberry built the foundations of his brand is once again positioned firmly at its core. Saddle and rain boots, field jackets and car coats were worn over them. Kilts and argyle knits, oversized rugby shirts printed with roses – for centuries England’s national flower – which in Lee’s hands are “not only red” (they are yellow and blue). Texture was rich: more roses, watery now, were spray-painted onto fluffy faux fur; dresses were all-over embroidered with tiny feathers in delicate shades. As technically accomplished as they were lovely, a reminder that alongside any iconography comes emotion – the touch of the hand. Finally that EKD was peppered through both clothes and accessories, from the insides of jackets and, magnified, rearing up across the entire front of a big white dress to the clasp of a bag called Knight (turned on one side it looks like a bridled horse). If attendees were expecting the same ice-cool fashion awareness with which Lee wowed the industry in his previous incarnation as creative director of Bottega Veneta, this was something completely different, warmer both physically and metaphorically, designed to be enjoyed by the many as opposed to the few, to uplift and entertain. Lee’s position at Burberry is among the most heavyweight in the fashion industry. In less than ten minutes his message had imprinted itself on the minds of all present, in a debut that was, conversely, youthful, optimistic, bright and brave. In a simply dressed, shadowy venue, in a London park, out of darkness into light, here was the new Burberry, shown after sundown but clear as day. And that is no small feat.

Daniel Lee was born and raised on the outskirts of Bradford, in the north of England, the eldest of three children. His parents still live there, a short drive from the factory and mill where both Burberry’s trench coats and signature gabardine are made. “The fabrics are made literally 20 minutes from where I grew up,” Lee says. “And the trench coats 20 minutes in another direction. Burberry is from that area. And the focus on outerwear for the collection goes back to that too. Being in the countryside you are so often outside. Being outside. Being in the countryside. Walking the dog in the rain. That was very much part of my life growing up.”

Susannah Frankel: I read that your aunt had a Burberry trench coat. Is there any connection to fashion in your family?

Daniel Lee: Absolutely zero [Laughing.]. I think that’s often the case though. For me there was always a desire to make things. I especially found joy in creative subjects. And fashion really was something I thought I could make a career out of. I realised that by the time I was about 18.

The city of Bradford, where Lee went to school, is unusual for its diversity – a characteristic provincial Britain is not always known for. “The outskirts are very green but the city itself is multicultural. My friends were all from completely different backgrounds, which is quite unique outside London and I’m thankful for that,” Lee says.

Certainly it smoothed the transition of landing in London, having been given a place first on the BA knitwear course, and then the prestigious MA fashion course, at Central Saint Martins. “Yeah, I was there for a long time,” Lee says. “I’d visited London as a child and I was so enamoured of the culture and the amount of people, the energy you see on the street. I think the variety and diversity of Britain, particularly London, is very special. I also really enjoy the conversations I have in this city. They’re interesting conversations because it’s such a mix of cultures. And there’s creativity and culture on so many levels. Fashion is one of them, of course, and the incredible fashion education, but also theatre, dance, literature, art, television, music. Saint Martins was a great experience, looking back. I still work with a lot of people I met there. Two of my design team at Burberry were in my class, we were all in the same year. It’s nice to have those relationships.”

DL: I grew up at a time when the designers making noise were Alexander McQueen and John Galliano, obviously graduates of Saint Martins. I think that’s how I came to it. I was really thinking, where did they go to school? I saw their work on the internet – it was at the beginning, when there was AOL dial-up – and I guess it was Vogue a little bit too. While at Saint Martins I did an internship at Margiela. That was the first job I had. Martin Margiela was still there. It was good. I arrived speaking no French, so it was challenging at the beginning. But it was a growing experience. And I worked for Nadège [Vanhee-Cybulski, now at Hermès]. After that I went to Balenciaga when it was designed by Nicolas Ghesquière. I worked with a guy who then became my boss at Céline. It was all very connected. At Donna Karan it was Louise [Wilson, then head of the Central Saint Martins fashion MA, who consulted for that brand].

“Balenciaga was a totally different experience. That was about uncompromised creativity, the joy of making things the way they have never been made before” – Daniel Lee

SF: Did you target those people for work specifically?

DL: I definitely targeted Margiela and Balenciaga.

SF: Why?

DL: Because Margiela, at that time particularly, everybody was obsessed with the work. It was 2007. The thing I responded to was really the method. And his work, it’s almost like an engineer’s. I think he worked around the same concepts time and time again to really perfect them in a way that doesn’t necessarily feel like fashion. The process didn’t necessarily feel like fashion and I think his process, certainly working there in the studio, was probably the calmest of anywhere I’ve been. It was quiet, it was very precise, there was a lot of precision, a lot of thought.

SF: And Balenciaga?

DL: Balenciaga was a totally different experience. That was about uncompromised creativity, the joy of making things the way they have never been made before. You really felt part of something working in that team. The hours were crazy, you were always in the office, but nobody cared. I enjoyed that experience so much.

SF: Someone once told me that Martin Margiela was worried that his mum and dad would be upset because he didn’t put his name on his label.

DL: Well of course they would be.

SF: Are your mum and dad proud of you?

DL: Yeah, very.

Lee watched and learnt from the best, even before he entered further education. His choices were deliberate, considered in the extreme. If any two designers symbolise the sheer creative energy of the British fashion education, so entwined with the history of the school they both went to, it is surely Galliano and McQueen. So Lee went to that school too. That Martin Margiela is among the most respected designers of the past century, a man whose aesthetic remains perhaps the most influential to this day, is taken as read. Less often cited is his branding strategy, which was equally transformative. The (non-) colour white was to Martin Margiela what black is to Comme des Garçons. Martin Margiela, the brand, started with the aforementioned labels, blank white squares roughly tacked into garments, and extended to the white coats (in French, they are called blouses blanches) those who staffed the ateliers wore, the walls and floors at its offices and all of its stores. Even the desks the employees sat at were white – they were in charge of painting and regularly re-painting those themselves. At Bottega Veneta, Lee shot to fame overnight with a collection that was almost entirely black. But it wasn’t long before he’d further defined the Italian brand using a bright emerald green, for packaging and punctuating his further predominantly black collections too. And now, at Burberry, alongside that check there’s Knight blue: for the EKD, for the written communications (the company’s press releases are sent out in that shade) and through the collections. For Lee’s second (Spring), arriving in stores in November, the taping on the inside seams of raincoats, the piping on silk pyjamas and on the new check Happy scarf are Knight blue. Labels are stitched into Burberry trench coats using thick Knight blue thread – a witty fil rouge. After completing his MA, Lee worked at Donna Karan – coincidentally, like one of Burberry’s previous chief creative officers, Christopher Bailey – before, in 2012, moving to Céline, which was then taking the fashion world by (quiet) storm under the artistic direction of Phoebe Philo.

“Céline was another experience where it was really important to push creativity,” Lee says. “What was genius about working there was the environment. Phoebe, together with Marco [Gobbetti, then Céline’s CEO] and LVMH, they built a studio and a set-up where it really was possible to have ideas, it was like a laboratory of ideas. Phoebe gave people the freedom and space to be creative, to come up with ideas that, if she liked them, she would push.” When Philo left Céline, in 2018, Lee was design director of ready-to-wear. In the short hiatus between her departure and Hedi Slimane’s arrival, Lee and the Céline studio designed a single collection, for Autumn 2018, memorable for its elegant understatement, its perfect restraint, its intense though discreet luxury. “That was good for me,” Lee says now. “It pushed me and gave me the confidence to take the job at Bottega. Otherwise I’m not sure I would have been able to do that.”

Even before he arrived at Bottega Veneta, the names on Lee’s CV read like a Who’s Who of international fashion. And that says almost as much about the scale of his talent and determination as what came next.

Lee was an out-of-left-field choice to take over as creative director of Bottega Veneta in 2018 – where he began with an off-runway pre-collection softly launched to press that December. Included in that first collection was a plump leather clutch bag with puckered edges, simply named the Pouch, that rapidly became a bestseller. Next came sharply square-toed shoes, the silhouette of which inspired a thousand imitations at every level from runway down, not to mention frenzied waiting lists for the real things. The house’s focus on artisanal craftsmanship was a gift for Lee: he supersized Bottega Veneta’s intricate Intrecciato woven leather and padded the strips to create bubbly, bulbous styles that seemed to be a cross-breed of Bottega’s traditional bags and a travel pillow, sometimes hung with a heavy gold chain, which became another runaway success, again much imitated. In his first runway show a few months later, Lee proposed complex leather coats and skirts of interlinked leather scales that resembled armour; later collections included hand-worked macramé, thick hand knits and ostrich-feather embroideries, pieces that succeeded in repositioning the hitherto sleepy if sophisticated label as a bellwether of all that is fashionable.

Ultimately, what his almost three-and-a-half-year tenure at the company proved to industry eyes was that Lee designed infinitely desirable clothing, for sure, but also had a knack for accessories – not only creating inventive industry pleasers, but products that resonate in real life. His rise was meteoric, even by famously meteoric-rise-loving fashion standards. At the Fashion Awards in London in 2019 he won no fewer than four gongs – more than any other designer has in a single year. Given his youth and relative anonymity, no one was more surprised than the designer himself.

DL: Bottega Veneta was like a blank canvas. It was a brand that people loved but they didn’t necessarily know very well. Tomas Maier [that label’s previous designer] was very discreet. It was a brand that stood for luxury. And quality. And aside from that it didn’t really mean anything. And craft. I feel that craft is innate to luxury fashion, that a customer of luxury fashion expects certain things, a level of savoir-faire, of quality, of innovation. Those are characteristics that no particular brand owns. They’re just generic to luxury fashion. The other thing about Bottega was that it was very new. It started, I think, in 1966, so it’s at the opposite end of the spectrum to Burberry. Outside woven leather there’s really nothing else that anyone knows. I saw it as a house of technique, so technique was the starting point, especially for accessories. And you can take that and use it in so many ways. It can mean so many things. It’s a bit like the check. You can work with that, with that one particular house check, or that one particular Intrecciato, and you can see it as a starting point.

SF: Were you surprised by people’s reactions to your Bottega? They were pretty extreme.

DL: I was very young. I didn’t really know what I was getting into. I remember taking the first step and thinking this will either work or it’s a huge mistake, there’s no middle ground. And, yes, I was very surprised. I still see iterations of what we did at Bottega everywhere, from the high street to other designers’ collections. And I like that, of course I do, because it makes you feel like you contributed something.

If one thing unites the five very different designers Lee worked for before arriving at Burberry it’s the fact that they remained, wilfully, behind the scenes. Unlike the superstar designers of the generation that came before them – and perhaps learning from the media circus that sprang up around that, not always with positive outcomes – they preferred that their work speak for itself. The sense is that Lee is instinctively aligned to that way of thinking. It’s not insignificant that the majority of Burberry’s Instagram posts since he arrived have simply read: #Burberry.

“The danger of this quiet-luxury thing is that it becomes ubiquitous” – Daniel Lee

DL: Yes, I’ve always been around designers who weren’t interested in having a media personality. But I definitely feel more comfortable today than I did when I started at Bottega, even though this position is vastly more visible and bigger in every sense. I was quite hidden at Bottega, because I took over from a designer who didn’t really do any press. At Burberry, though, I feel there is a responsibility to speak. Burberry has a different role in society. It is more than a fashion brand. It’s an institution. It’s a symbol of a country. There’s a huge number of employees. It’s a weightier position. And I think the success of the Christopher era was that he was very open-door.

SF: Does it annoy you that people compare you to Christopher Bailey? I suppose you do look quite similar.

DL: At this point our industry is full of comparisons.

SF: But why is that, do you think?

DL: Because it makes things easier to understand. So you’re the minimalist or you’re the maximalist, you’re the vocal designer or you’re media shy.

SF: I think people maybe imagined your Burberry would be minimal.

DL: But the kind of fashion that I like is about the things that make you think and feel, and product that you can’t necessarily find anywhere else and that ultimately you have an emotional attachment to. The danger of this quiet-luxury thing is that it becomes ubiquitous.

Having designed and shown his first collection for Burberry, and delivered the accompanying ad campaign – again with Tyrone Lebon and, again, outside but now travelling to the Giant’s Causeway in Northern Ireland and the Isle of Skye in Scotland – Lee attended the Burberry-sponsored opening party of this year’s Royal Academy Summer Exhibition (there was a Burberry brass band in the famous courtyard) and designed the costumes for a ballet at the Royal Opera House, choreographed by his friend Wayne McGregor: they were white and green. Lee also worked with McGregor in 2021, designing the costumes for the Venice Dance Biennale that same year.

“I think it’s important for Burberry to support the arts, particularly now where government cuts are affecting culture and fashion is still, let’s say, doing well,” Lee says. “The Royal Academy, again, is an institution of British society. And Wayne is someone I’ve known for quite a long time now. He’s a friend. I’ve been seriously interested in theatre since I was very young. I went to theatre school when I was a child. It never became a career because I’m working in fashion now, but I do go to the theatre a lot and I’m very happy to be a little part of that world. Dance is a particular passion for me. It’s amazing, the determination and persistence involved.”

Determination and persistence are both characteristics that might fairly be applied to Lee. “And conviction,” he says. If his debut collection for Burberry felt like an exercise in shifting and rebranding – a reset (his own words) – Spring evolves into a more developed statement, cut closer to the body, with more focus on tailoring and silhouette. Imagine hour-glass tailoring with peak lapels in traditional Savile Row fabrics – houndstooth and Prince of Wales check warped. Rubber raincoats and boots, with visible check linings showing through their transparent surface or punched with the outline of the EKD, half on one boot, half on the other. Outerwear details now migrate onto more dressed-up garments, an adjustable collar and silver metal press studs on a silk gazar dress, a hood attached to the ruffled collar of a voluminous chiffon gown.

SF: What do you do when you’re not working? Do you ever not work?

DL: Not really. But I love my work, so everything feeds into that – going to an exhibition, to the theatre, a ballet, a concert. Everything feeds in. I really enjoy the physicality of making things and the fact that you don’t have to overthink. It’s more of an instinctive process, more primal. And then I love to give what I make a context and that’s given to you by other people and the contacts you make, the people you put the product on. We’re just at the beginning and it’s an evolution – we’re becoming more comfortable, building a team, a way of working. As the custodian of a brand that has been around for so long, I feel that every chapter is important.”

“What I would love to do is write an important new chapter for Burberry,” Daniel Lee says.

Hair: Andrea Martinelli at MA+Talent. Manicure: Lauren Michelle Pires at Future Rep. Models: Arthur Del Beato, Monica Majak, Jennifer Matias and Mohammed Abubakar at Milk Management, Clementine Chalfant at Wilhelmina, Tehya Elam at Premier Model Management, Prince Gasinu at Menace Model Management, Mairyn Miller at Next Model Management, Eva, Olaolu Slawn and Beau Slawn. Casting: Mischa Notcutt at 11 Casting. Movement director: Emmanuelle Loca-Gisquet at New School. Set design: Harriet Ellis-Coward at Studio Augmenta. Lighting: Darren Karl-Smith. Styling assistants: Molly Shillingford, Honor Dangerfield and Imaan Ashraf. Tailor: Ben Dufort. Hair assistants: Tobia Bartolini, Muriel Cole and Marco Iafrate. Barber: Tariq Howes. Make-up assistants: Quelle Bester, Chantal Amari and Temi Adelekan. Manicure assistant: Abena Robinson. Set-design assistants: Asya Peker, Roisin Jenner and Toby Caldicott. Printing: Labyrinth and Artful Dodgers. Production: Liberty Dye and Toby Ramskill at Concrete Rep. Post-production: The Hand of God

This story features in the Autumn/Winter 2023 issue of AnOther Magazine, which is on sale now. Order here.