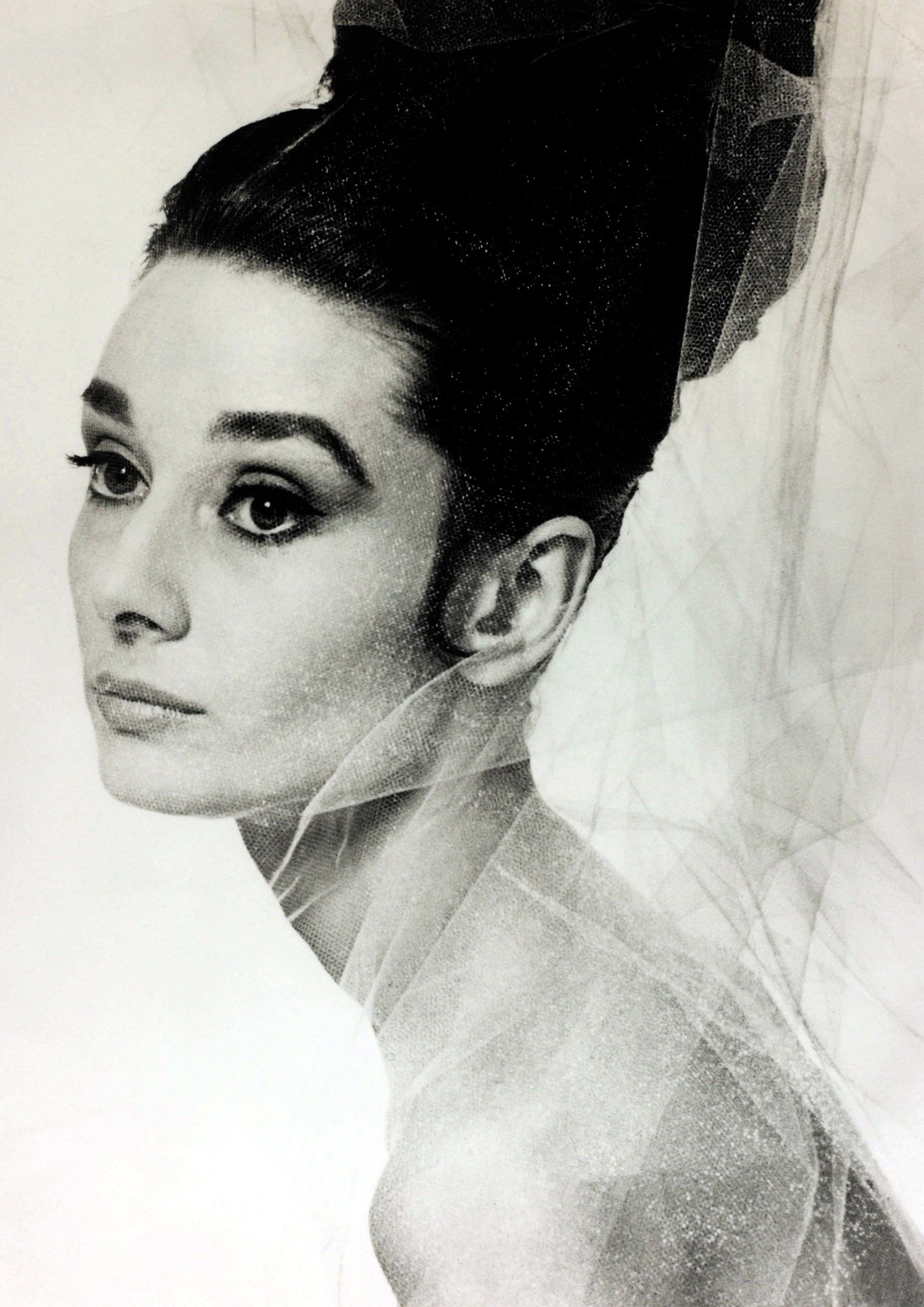

As Truman Capote noted, muses are heard. They are heard every time a poet writes, an artist draws, or a designer drapes. Homer invoked this ethereal sorority at the opening of The Odyssey, and Dante summoned them before plunging into his Inferno: “O Muses... aid me now!” In fashion, Paul Poiret’s career did not long outlast his marriage to his obliging muse Denise, whom the fabled designer at one point literally locked up in a gilded cage. Christian Dior was enraptured by the excessive, exaggerated beauty of Mitzah Bricard, a human panthera wrapped in pearls. Yves Saint Laurent, for his part, assembled around him a formidable entourage of exotic personalities, each personifying a distinct facet of his taste. This week, an exhibition opens at the Gemeentemuseum in The Hague that explores the eternal love affair between the world’s favourite designer-muse duo, Hubert de Givenchy and Audrey Hepburn. Givenchy never saw Hepburn as a pet-like source of inspiration, but rather a lifelong companion who was just as much an emblem of the golden age as he was – they became so close that he was a mediator of her will and a pallbearer at her funeral. Their relationship is one that has sent millions of hearts aflutter, because, well, who doesn’t love Audrey Hepburn? She was the gamine symbol of post-war youth and doe-eyed femininity, and he, de Givenchy, the man who cut exquisitely fuss-free clothes that echoed her elegant sensibility on her slender silhouette.

It is no secret that Hepburn was outfitted for life by the couturier, always faithful and unwavering in her support. The concept of lifelong loyalty to just one designer may seem anathema to the modern condition, but then it is an inconceivable luxury to cast off the shackles of shopping and go to Paris for a tailor-made couture wardrobe. This is the stuff of fashion dreams; it is what underpins the fantasy of haute couture and allows us to dream of a life in which we are dressed as the best versions of ourselves.

We can all but dream of sauntering into a couture salon and finding our style’s soulmate, just like Audrey did in 1953 when she sought out de Givenchy to create her costumes for Sabrina, the story of a simple girl who goes to Paris and returns as the embodiment of sophistication. Their relationship is one that transcends paid-for appearances and the wear-it-once culture of Hollywood ‘muses’ today, yet it is also a relationship that informs it. The Hepburn-Givenchy romance is symptomatic of a time when the couture houses weren’t selling sweatshirts and sneakers to account for their bottom line, and style was more about the life that one lives in the clothes, not the clothes themselves.

“She invited me for dinner, which was unusual for a woman to do back then, and it was at dinner that I realised she was an angel.” Hubert de Givenchy

“I was expecting Katharine Hepburn,” recalled de Givenchy at the opening of the exhibition last week. “I was quite astonished when this young, small, sparkly girl showed up.” As the story goes, Hepburn was then a much lesser-known starlet and wanted the young couturier, who had only set up his own maison the prior year, to design her costumes for Sabrina. “I don’t think she had ever seen a piece of haute couture before. She came in a striped T-shirt and trousers and tried on a couple of the samples,” he continued. “I was busy preparing my next collection so I told her I wouldn’t be able to do it, but she was very persistent. She invited me for dinner, which was unusual for a woman to do back then, and it was at dinner that I realised she was an angel.” The two became close and it marked the start of a marriage that would originate some of the most iconic on-screen fashion moments. “Because of her, I was able to change the look of the Hollywood icons and she would request that it be written into her contracts that I would design her clothes, which were the first contracts of this kind.”

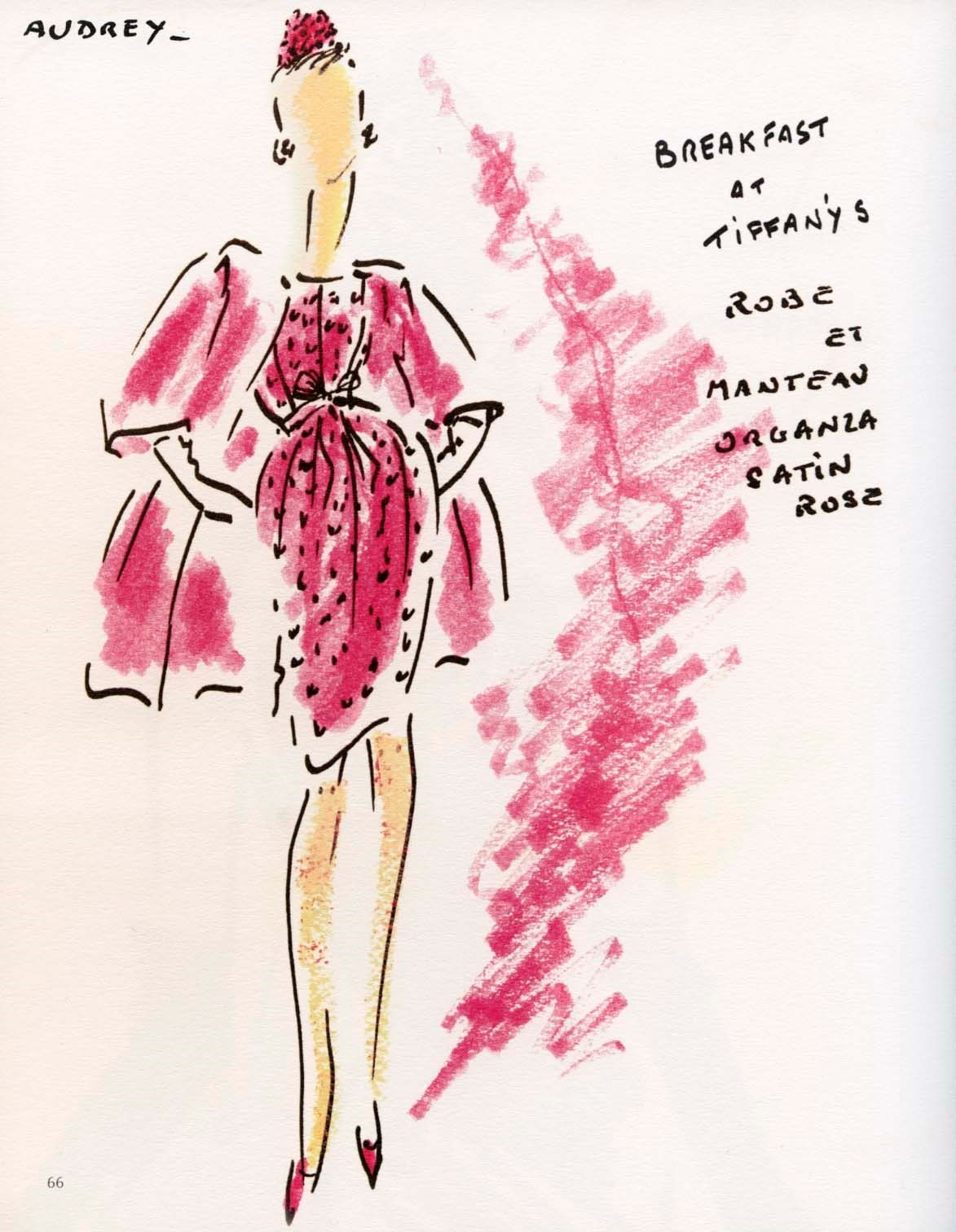

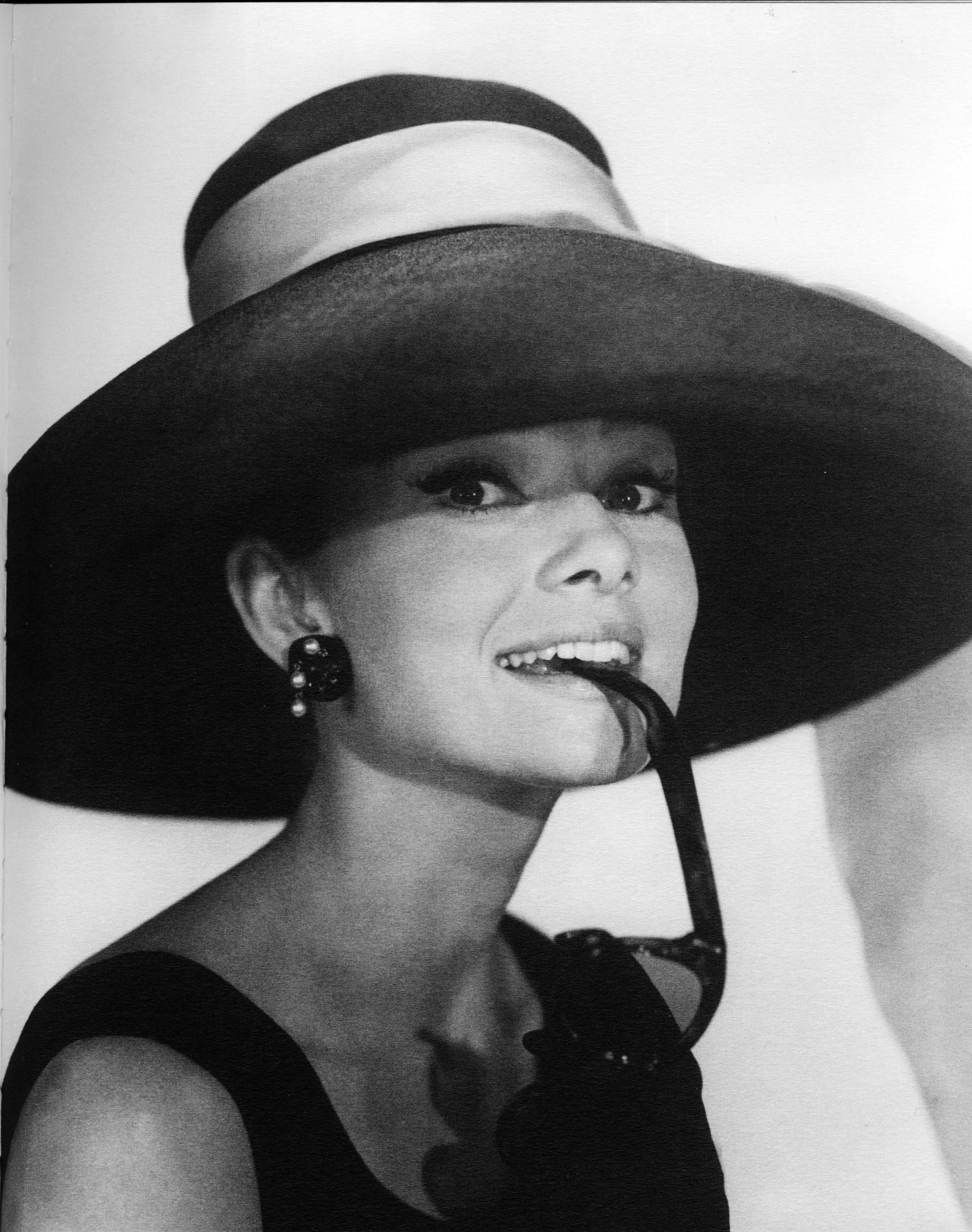

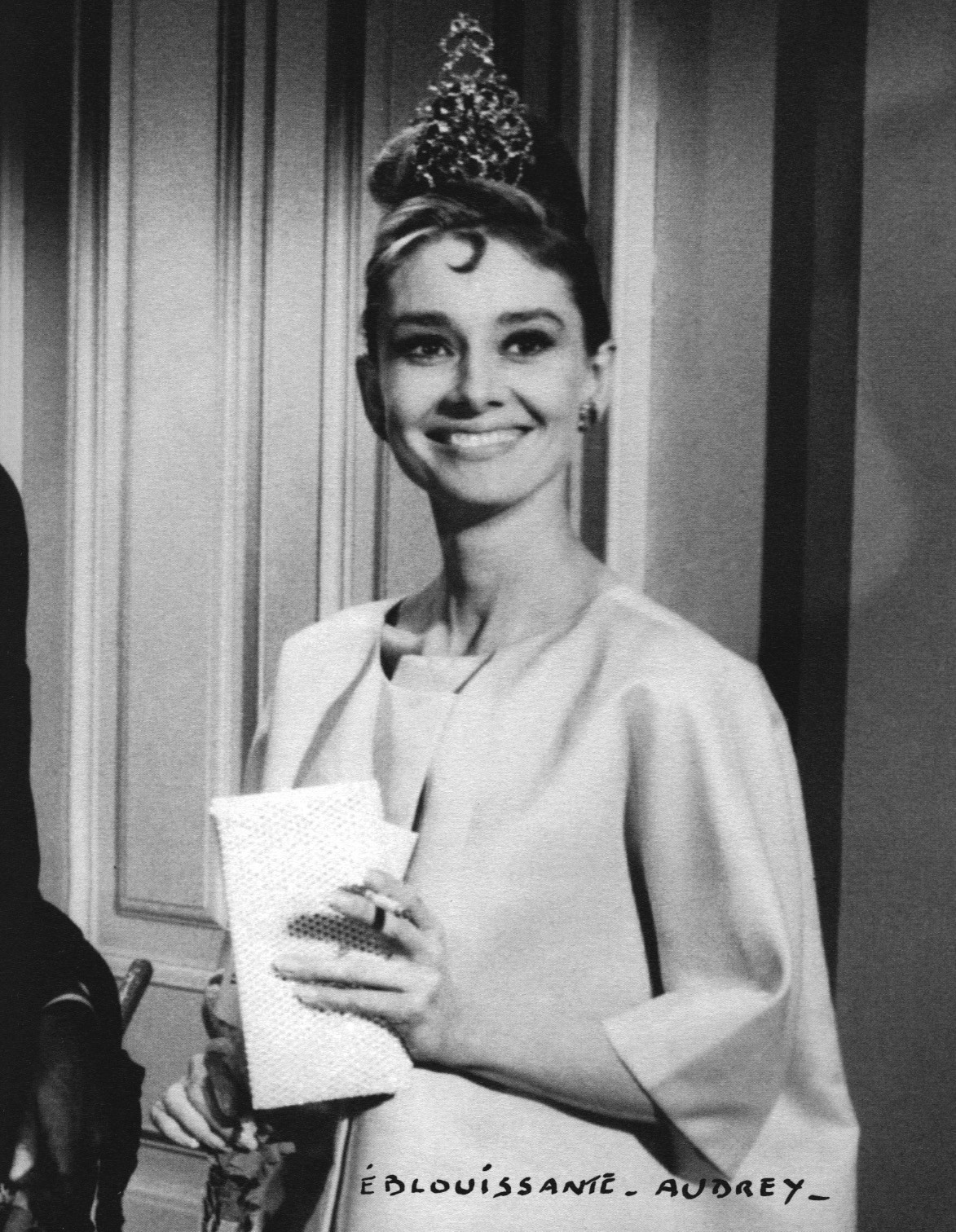

On display are a spellbinding assortment of Hepburn’s finest Hollywood costumes, set against screens showing her wearing them in scenes. Of course, there is that long black silk dress, complete with the strands of globular pearls, which we see Holly Golightly gaze through the windows of Tiffany’s in. There’s also the columnar strapless scarlet satin dress that Hepburn models with the grace of a ballerina on the Louvre’s Daru staircase in Funny Face, as well as the intricate black lace number and matching face mask from How to Steal a Million and a shocking pink cocktail dress and satin capelet that Golightly furiously trashes her apartment in.

There are these, and many more, as well as wider highlights from Givenchy’s long career, and some of his other contributions to pop culture – such as the black wool and leather coat with matching veil that he whipped up in a single evening for the Duchess of Windsor when she was let back into England to attend her husband’s funeral and dramatically reunite with her unimpressed in-laws. Or the floral embroidered satin gown he made for Jackie Kennedy for her and her husband’s 1961 state visit to France, which caused President de Gaulle to comment, “Tonight Madame, you are looking like a Watteau”.

“Clothes are positively a passion with me,” Hepburn confided to a journalist on the set of Sabrina. “I love them to the point where it is practically a vice.” Though she was always loyal to her dear friend, by no means was she a clotheshorse. Some of her most charming Givenchy pieces are the boat-neck (to cover her exaggerated collarbone) satin T-shirts that she wore with jeans, and the two-piece trouser suits that she sported out and about. As the newspaper La Croix conceded upon the release of Sabrina, Hepburn “had become a Parisienne down to the tips of her fingernails.” She described de Givenchy as “a creator of personality” and acknowledged how important his work was in her career. “It was often an enormous help to know that I looked the part,” she once explained. “Then the rest wasn’t so tough anymore. Givenchy’s lovely simple clothes [gave me] the feeling of being whoever I played.”

The exhibition, which is staged in Holland partly because Hepburn grew up there during wartime, is a glimpse into a relationship that seems so utterly missing in today’s fashion landscape. Perhaps the impact of the muse has waned as we have entered a prevailing era of magpie consumerism. Who, after all, lives their life wearing one or two devoted designers nowadays? And why is nobody making films with fabulously extravagant costumes anymore? Today, we feel empowered and overwhelmed by the cornucopia of consumer choices that haunt our timelines and sneakily find a way into our subconscious.

Observing Audrey Hepburn’s wardrobe of perfectly tailored Givenchy, one may be forgiven for wondering whether eliminating the bother of wading through a plethora of products, a cornerstone of capitalist freedom, is in fact the most empowering choice to have – especially for an actress or public figure expected to make endless appearances. Then again, Audrey Hepburn wasn’t just any actress and Hubert de Givenchy wasn’t just any designer. This is a story about Hollywood and haute couture – and it doesn’t get dreamier than that.

Hubert de Givenchy: To Audrey with Love is open at the Gemeentemuseum in The Hague, Holland from November 26, 2016 to March 26, 2017.