The life of the world's most famous ballet dancer is recalled through his personal collection shot exclusively for the latest issue of Another Man

He was the world’s greatest dancer, a legend of late night revelry and an obsessive collector of antiquities but behind all the opulence and hedonism hid a solitary figure. With exclusive access to his personal objects, Another Man piece together the real Rudolf Nureyev, as it is memorialised in these exquisite still lifes shot by Julia Hetta.

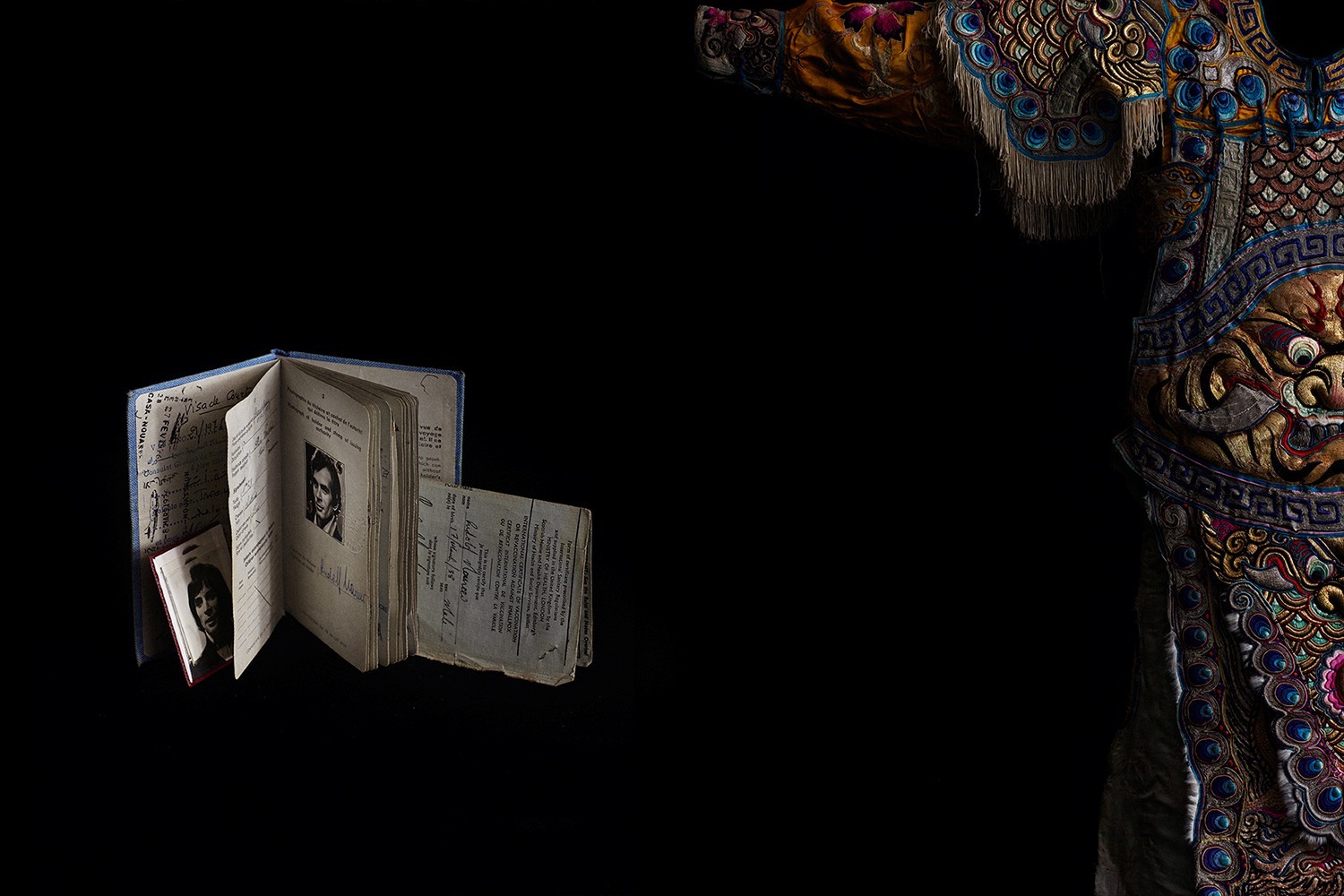

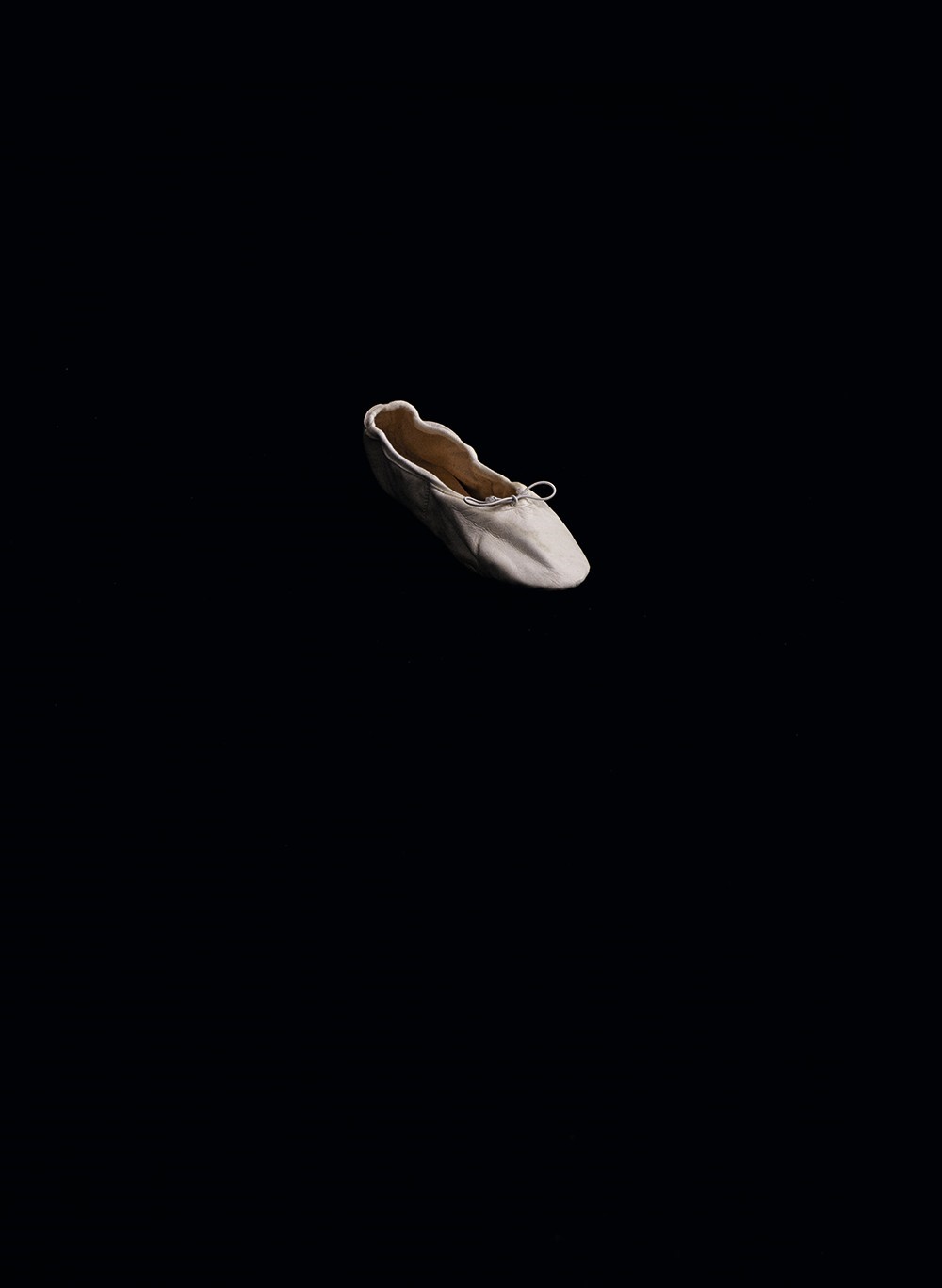

When Rudolf Nureyev broke free from his KGB shadowers, dashing across a Paris airport lounge to request asylum in 1961, he started his new life in the West with just the clothes on his back and a pair of ballet slippers. By the time of his death in 1993, he had amassed a fortune of $21 million, including seven lavish properties: a mansion near Richmond Park, an apartment in the Dakota, an airy villa overlooking the bay of Monaco, a 415 acre Virginian farm, a trio of rocky islands off the Amalfi coast, a house on St Barth (where he’d wander the beach nude except for a waterproof Walkman), and a sumptuous apartment on Quai de Voltaire with views of the Seine and the Louvre. “Everything I have,” he declared, “the legs have danced for.”

An insatiable collector with a magpie eye and extravagant tastes, the Russian dancer filled his houses with rare, exotic purchases culled from his travels through Istanbul, Venice, the Greek Islands and beyond. A spectacular auction at Christie’s disposed of thousands of his possessions in 1995, but 300 talismanic pieces were preserved as the Rudolf Nureyev Collection, finding a permanent home recently at the Centre National du Costume de Scène in Moulins, an elegant town of honey-coloured stone and crumbling art deco cafés on the banks of the Allier river. Three hours south of Paris, it’s an incongruously quiet place for Nureyev’s unrestrained taste in decor: his decadent Parisien lair at 23 Quai de Voltaire is lovingly recreated inside the museum with Kerelian birchwood furniture, ornate clocks, Renaissance tapestries and dark Cordovan leather walls forming the backdrop for the dancer’s penchant for 19th century male nudes. Clad in one of many brocaded Japanese kimonos, Nureyev would lounge amid his finery like an animal in his natural habitat, his feet steeped in layers of Turkish kilim rugs (distrustful of banks, he kept wads of cash under them).

If he was notorious for never picking up a restaurant bill, the dancer was infinitely generous with himself: objet d’art, costumes, furniture and paintings were all bought with a favourite phrase, “from me to me”. Following an evening’s performance at the Paris Opera Ballet, he’d take nocturnal strolls around the Left Bank’s antique shops – dealers wised up to his nightly routine and would place objects that might appeal in their windows before locking up. Every new purchase intoxicated him: “I would fondle them for hours, smooth them and smell them. There is no other word to describe it – I was like a dope addict.”

His addiction might have been revenge on a childhood of crippling poverty, of “constant, gnawing hunger”. It was sheer force of personality as much as profligate talent that drove the Tatar boy step-by-step from a single-room apartment shared with three families in a backwater Bashkir province, to St Petersburg, the Kirov Ballet, and eventually, to freedom and fame in the West. The exuberant, wild-eyed dancer became a celebrity within hours of his defection and he was never reluctant to claim the limelight. He had written his memoirs by 23, could command 40 curtain calls a night at the height of “Rudimania”, and if critics occasionally complained his technique wasn’t faultless, audiences didn’t care: he was a natural, maddening, untameable star, the tempestuous “Brando of ballet”. At his New York debut, future friend Jackie Onassis described applauding until her hands were “black-and-blue pulp”.

Onstage, Nureyev made sure to outshine his ballerinas in elaborate costumes of his own design, thick with embroideries, braids and gems, and, in thighhigh boots and snakeskin coats, he was no wallflower offstage. The gold leather jacket seen here was purchased at Mr Fish in Mayfair, and seems likely to have done time at Annabel’s. His stamina was inexhaustible: in 1965, Time magazine recorded plying Nureyev with caviar at London’s Connaught until the hotel’s supply ran out, before nightclubbing till 4:30am. But whether he’d been dancing at Regine’s with Bardot, downing Stolichnaya or satisfying a ravenous sexual appetite cruising Manhattan’s meatpacking district, he saved his best for ballet: however late the night, he was pirouetting at the barre early the next morning. Nothing could drag him from the stage: he once danced in Paris with pneumonia and a temperature of 103, flew straight to LA to perform again, before being rushed to hospital by a doctor waiting in the wings. Even his petulant tantrums had theatrical flair: costumes that displeased him were torn to shreds or thrown out of windows, ballerinas who’d put on weight would be simply dropped in mid-air. During a disagreement at the Paris Opera Ballet he broke one teacher’s jaw, and was sued for 2,500 Francs. “If I’d known it would be that little, I’d have hit him a second time,” he shrugged.

But for all the glorious excess, the most intriguing pieces in Nureyev’s collection are the least flashy. They hint at the psychological pressures of exile, and reveal a strange mass of contradictions within the volatile dancer. Despite his material wealth, he travelled the world with the simple battered leather bag seen here – all he really needed were ballet shoes, a woollen sweater and leotard. A lifelong nomad who was famously born on the Trans-Siberian express, Nureyev never settled anywhere long; his houses were more like stage sets than real homes. And while the international jet set – Liza Minnelli, Andy Warhol, Yves Saint Laurent – are scribbled into the pages of his address book, he suffered the deep loneliness of a stateless soul. Retreating to his isolated Amalfi coast islands, Li Galli, he’d spend days watching old Fred Astaire movies, jumping on his Kawasaki jet-ski and driving full-tilt at tourist boats if they sailed too close.

“I have only one dream. Always the same,” he said in Paris. “That one day I can receive my mother here. It’s her I am waiting for.” He paid a high price for grabbing his freedom: Farida Nureyev was never granted permission to leave Russia. By the time he was allowed to visit her in 1987, she was gravely ill, unable to open her eyes or speak; she died soon afterwards.

All but erased from Soviet culture for the “betrayal” of his native country, Nureyev was typically unrepentant – his well-worn, all-American NASA baseball cap suggests a streak of black humour at his status as one of the most famous cultural figures to defect at the height of the Cold War. And yet, he never quite shook the Russian soil from his roots. He created a mini Bashkirian idyll surrounded by silver birches at his farm in Virginia, and in his final years, HIV-positive and suffering increasing ill health, the dancer with a seemingly unquenchable appetite for applause, luxury and sex, began to sleep on his kilims as though he were camping on the Steppes. Nureyev lost his fierce battle with AIDS in 1993. Electing to be buried in Russian Orthodox cemetery Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois rather than choosing the company of Wilde, Proust and Morrison at Paris’s Pere Lachaise, his grave is an eloquent epitaph for the selfconfessed “vagabond soul”. Built by set designer Ezio Frigerio, an exquisite oriental kilim made of thousands of colourful mosaic tiles drapes itself over his coffin: the eternal nomad, ever ready to fold up his belongings, and move on. Ultimately, it’s his footwear – a pair of scuffed naval shoes, a crumpled ballet slipper – that are the most poignant artefacts among Nureyev’s surviving possessions. His utter dedication to dance was the single unifying factor of his extraordinary life, and it was onstage that he found his true home.

Special thanks to the Centre National du Costume de Scène. This story first appeared in Another Man S/S15, out now.