A new exhibition celebrates the Polaroids of “master of light” Robby Müller, who worked as a cinematographer alongside Wim Wenders, Jim Jarmusch and Steve McQueen

The late Dutch cinematographer Robby Müller was one of the greatest pioneers of his medium. Frequently referred to as a “master of light”, he was a daring proponent of experimental camerawork who demonstrated the immense power of cinematography to contribute to the mood and meaning of a story. He is best known for his collaborations with Wim Wenders on such visionary films as Alice in the Cities (1974), The American Friend (1977) and Paris, Texas (1984); Jim Jarmusch, for the exquisitely rendered Down by Law (1986) Mystery Train (1989) and Dead Man (1995), among others; and Lars von Trier on Breaking the Waves (1996) and Dancer in the Dark (2000). Müller only took on scripts that he felt offered honest insight into the human experience and he in turn would lend his acute aesthetic sensitivity to conjuring up the worlds they depicted. “There’s a certain kind of magic... to whatever he shoots,” British director and Müller collaborator Steve McQueen told The New York Times. “I compare him to a blues musician in a way. He plays just a few chords and he conveys what he needs to convey.”

This was also true of the many photographs Müller captured throughout his life – an important, albeit lesser-known facet of his work. Next month, a new exhibition of his Polaroid works will open in Arles, to coincide with the 50th anniversary of the famed Les Rencontres D’Arles photography festival, allowing a deeper understanding of the inimitable imagemaker’s practice one year after his death. “Robby was always taking pictures,” Andrea Müller-Schirmer, the cinematographer’s wife and curator of the exhibition, tells AnOther. “When we went on vacation he’d have about seven different cameras to hand – a film camera, a Polaroid camera, a widescreen camera, and then he’d always carry a small Minolta in his jeans pocket. With Polaroid I think he liked the square format, the emulsion finish, and the fact they were instant.”

For Müller-Schirmer, it was this factor that made the Polaroids the most logical starting point in the exhibiting of her husband’s photographic output. “And because they’re incredibly beautiful,” she says. “Often Polaroids fade and go a greenish colour over time, but the colours in Robby’s pictures have stayed so strong. I think it’s because he kept them in the dark, like drawings – but only for himself. I think he made these little artworks just for him; the films were what he intended to be published. He never thought of himself as an artist or a photographer. But later, when we published the Robby Müller: Polaroid book, he liked it – he liked that other people liked it!”

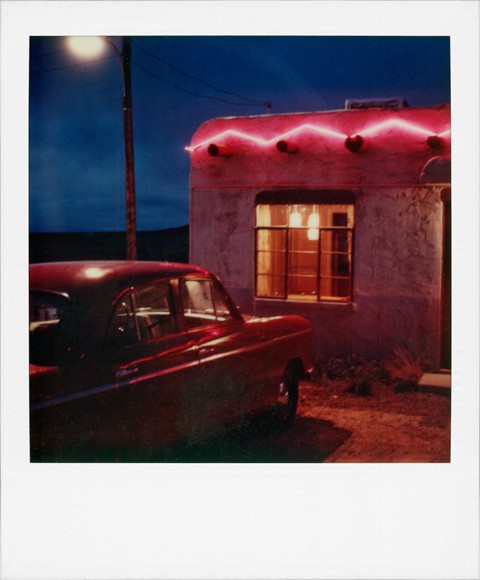

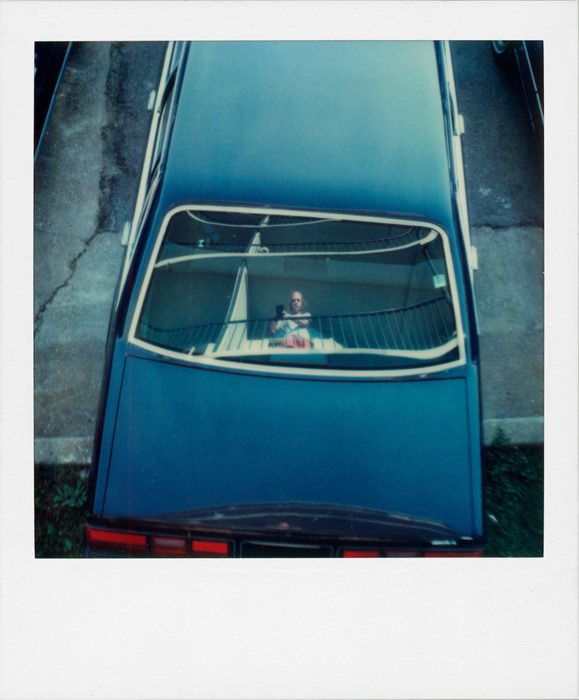

The show will comprise of over 100 works, taken between the 1970s and 1990s, and presented according to theme. The painterly quality of the Polaroids is just as stirring as that which defines Müller’s cinematic oeuvre – proof, if any was needed, of his total command of tonality, lighting and staging. Many of Müller’s most characteristic traits are identifiable within the works. His interest in reflection, for instance, is demonstrated by a stirring snapshot of a sea of yellow New York taxis, their distorted mirror image revealed in the shiny architecture of an adjacent building, as well as various, playful self-portraits captured in the reflection of a round silver lamp or car windscreen. Much of Müller’s working life was spent on the road while on location for shoots, and many of the show’s most arresting pieces were taken in the United States – in an artificially lit Greyhound station or an atmospheric motel room – offering the uniquely European take on Americana that Müller and Wenders were celebrated for.

Elsewhere, still lifes of such mundane objects as a pink shirt or simple stove kettle are imbued with an otherworldly charm by the light which infuses them. As Jim Jarmusch says of Müller in Living the Light, Claire Pijman’s 2018 documentary homage to the DoP, “it’s about the variations of daily details and Robby’s incredible brilliance as a person is appreciating the details”. This likewise applies to the myriad photographs of nature included in the show, most of which have not been seen before. “Nature was something very personal and beautiful to Robby,” explains Müller-Schirmer of the visually sumptuous shots of trees, plants and flowers. “Flower imagery can be quite kitsch; it often resembles botanical books from the 70s. But Robby had this eye for a silent type of beauty, whatever he was shooting. It’s not something loud – ‘I’m here, look here!’ – it has a poetic quality.” And indeed, it is this profound appreciation for life’s inherent lyricism – which Müller so gently invites us to share in and meditate upon – that makes his work so moving to view, whether encapsulated in motion picture or instant snapshot.

Robby Müller: Like Sunlight Coming Through The Clouds is presented by Polaroid at the Place de la République 12, Arles, France, from July 1 – 31, 2019.