The photographer purges her bookshelves to piece together new works currently on display at Higher Pictures Generation in New York City

In June 1968, Valerie Solanas, radical feminist and self-professed thrill-seeker, walked into Andy Warhol’s Factory with a gun and a recipe for retribution (it was alleged that he had misplaced a manuscript of her play, Up Your Ass). She fired at the artist three times, leaving him declared dead at one point. While a wounded Warhol slowly recovered in hospital, public attention quickly gravitated towards Solanas’ writings, most notably her notorious SCUM Manifesto, which she had sold the previous year on the streets of Greenwich Village: $1 for women, $2 for men. In it, she declared her one-woman club, SCUM (Society for Cutting Up Men), would “bring about a complete female take-over, eliminate the male sex and begin to create a swinging, groovy, out-of-sight female world.”

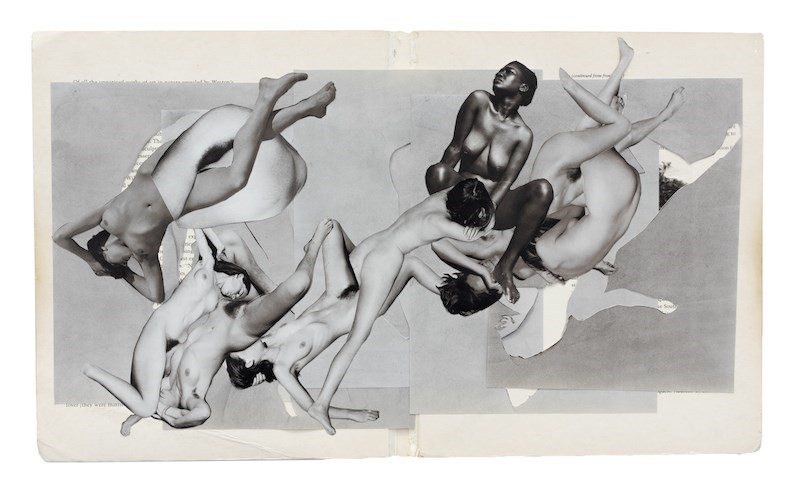

Over half-a-century later, Justine Kurland dared to inhabit Solanas’ rebel spirit and channel it towards her cherished collection of photobooks, 99 per cent of which was authored by white men. Working alphabetically – from Atget and all the way through to Weston – she slashed it up. “This is what the canon looks like,” says Kurland. “It’s subtle and insidious … a set of aesthetic and moral values, consciously or unconsciously held, that institutionalises white male power. Cutting my books literally freed space on my bookshelves but also in my brain.” The remains, pasted back onto their respective endpapers, currently hang on the walls at Higher Pictures Generation in New York City.

Kurland’s collages are less about rewriting history (she adds a “B” for “Books” to Solanas’ society name), and more about cannibalising it. “I learned the language of photography through these photographers. But, at the same time, my love for their work annihilates any possibility of me making work,” Kurland explains. “I felt like I was collaborating with what I wanted to see from these books; what was already inherent. I remember reading an article about these ants in South America who ate the brains of other ants so that they could know what that ant knows. I felt like I was marching into these books like ants.”

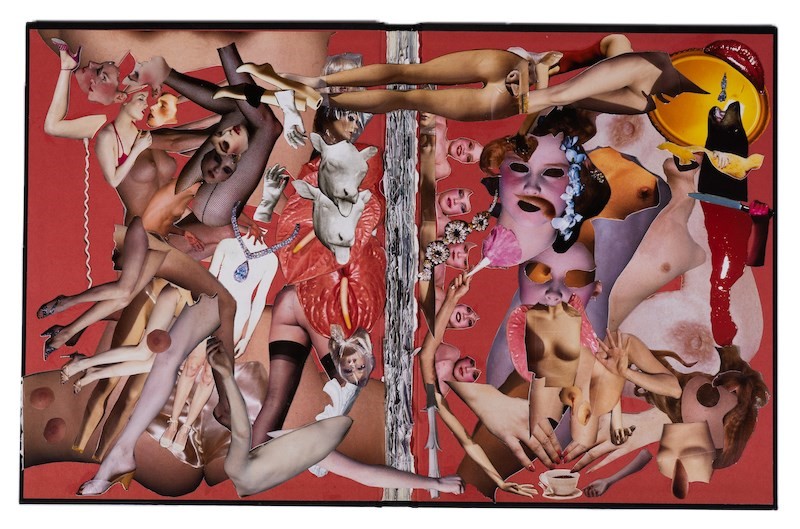

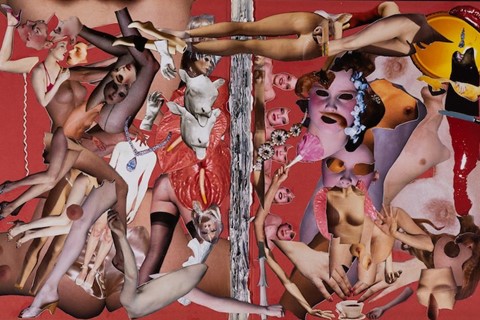

Ever since Dadaist Hannah Höch took her kitchen knife to the glass ceiling, photomontage has oft been employed as a feminist tactic to dismember patriarchal codes and domestic trappings: think Martha Rosler’s anti-war satires or Linder’s erotica-furniture mash-ups. What we find in Kurland’s cyborg creations is something brutal but also benign. Female bodies – freed at last from the constraints of the old century – are thrown into woozy, wayward choreographies, rhyming and colliding across the endpapers. Bare legs leap, lunge and sing hosanna to their newfound worlds; worlds in which female sexuality is expressed on female terms – and not for male consumption.

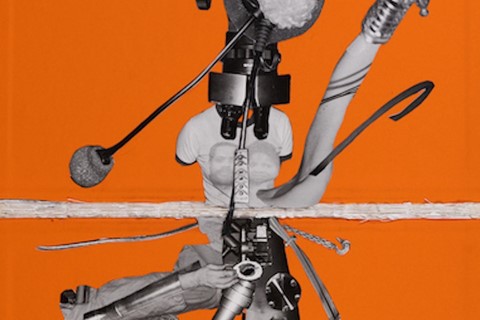

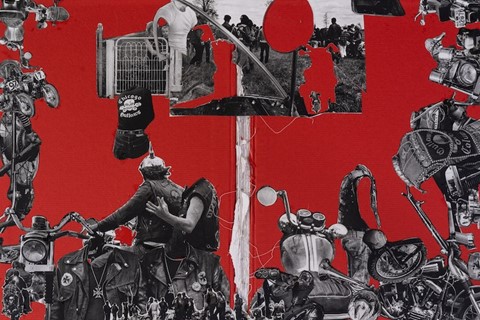

Yet, for all their illicit thrill, there is also a searing political discontent that has amassed through the ages. Lee Friedlander’s photographs of statues commemorating historical generals, statesmen and patriarchs have been melded into one almightily botched mess, while Stephen Shore’s shots of the American road – since time immemorial a “men-only zone” – crackle with kitsch and quirk courtesy of Kurland’s rejigs. As for Danny Lyon’s 1968 book chronicling the Chicago Outlaws Motorcycle Club, what happens when the red-blooded gazes, libidinous cues and slicked quiffs are ousted, and all that’s left is a heap of pipes, wheels and moto jackets? Indeed, biking has never looked so utilitarian.

Perhaps Kurland cuts to the chase, fast-tracking us to the all-female future which Solanas made the case for in the 60s. Yet, in “foregrounding women’s experience as something primary and irrefutable,” as she puts it, the collages ultimately serve as an extension of her life-long pursuit of matriarchal utopia. In one collage, tree trunks form the word: “Valerie”. In another, “Justine” is made via abscised limbs (and a breast to dot the “i”). “The political is personal, and the personal is political,” says Kurland. “Though it does make me laugh. Spelling out my name hasn’t become less funny or delightful, that’s for sure.”

Justine Kurland, SCUMB Manifesto is at Higher Pictures Generation until 1 May 2021.