Delving into her vast found photography collection, the artist considers how instructional images can – beyond teaching us practical, life-building skills – proffer ontological truths about our bodies and world

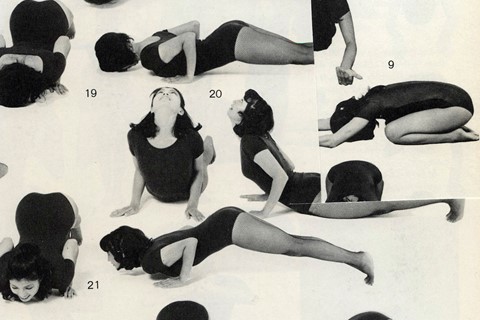

Carmen Winant says that Julio Cortázar’s Cronopios and Famas (1962) – a book that opens with a series of stories providing instructions on how to sing, cry and be afraid – is often in mind. It is also the point of reference for her ambitious new book, Instructional Photography: Learning How to Live Now. Unfolding like a call-and-response poem, it weaves Winant’s pithy texts with images showing hypnobirthing, dog training, rock climbing, braiding, triple axels, self-defence methods, home pap smears, tai chi and the sitting Shiva. The knowledge these images bestow undoubtedly has a utilitarian function, but the brilliance of Winant’s book is in demonstrating how the transient can become transformational. “In a moment ... of heightened anxiety and re-imagination,” she writes, “I want, on these pages and together, to investigate the potential of photography to teach us how to live.”

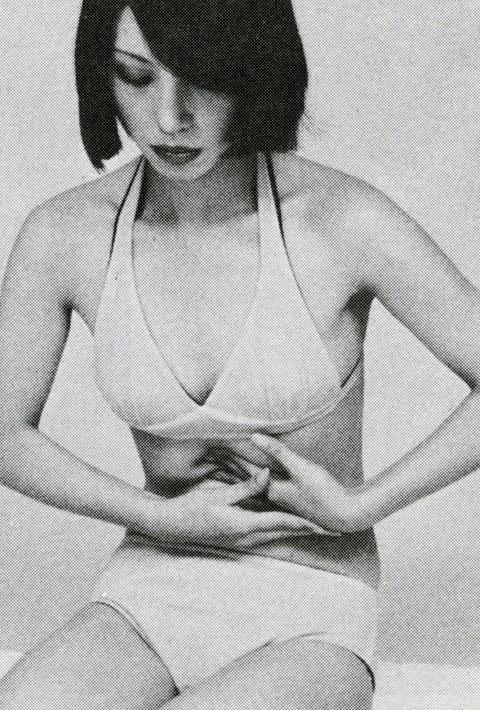

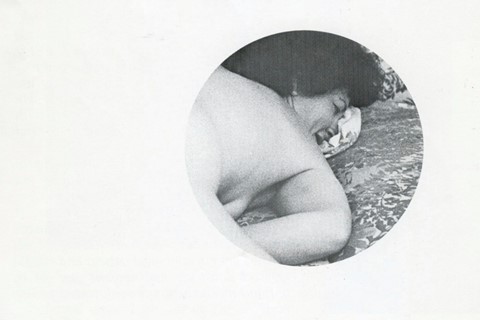

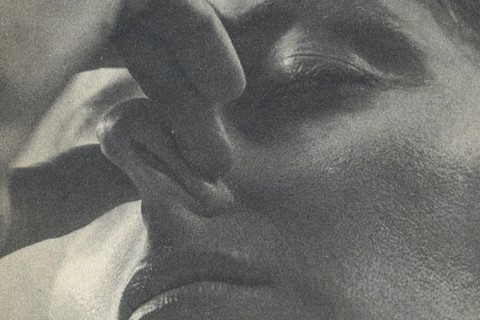

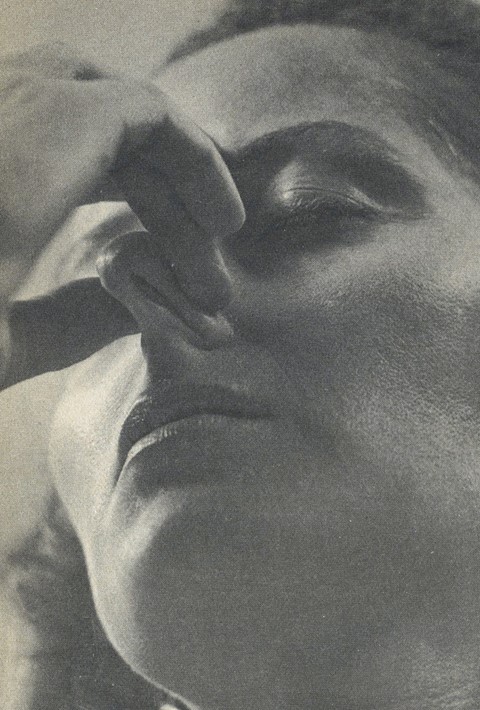

Although the images Winant compiles are untethered from the chilly confines of the gallery wall – a context Winant associates with an “orgiastic capitalism” – this isn’t to say they don’t bear affinities with what we call “fine art photography”. A dog’s leap through a flaming hoop is caught with textbook precision, while the close-crop of a woman’s self-breast examination is abstract like a seashell. As always for Winant, the aesthetic idiosyncrasies of printed matter only deepen the beauty and intrigue. On her copy of I Am My Lover (1978) by Joani Blank and Honey Lee Cottrell – a book about vulva types and masturbation – Winant writes: “[It] came with a faded, yellow stain on its cover. It seeps across the closely cropped face of the topless model on the cover … I’ve since become obsessed with the stain – uneven and soft, like a birthmark, like a piss cloud – and its possible origins.”

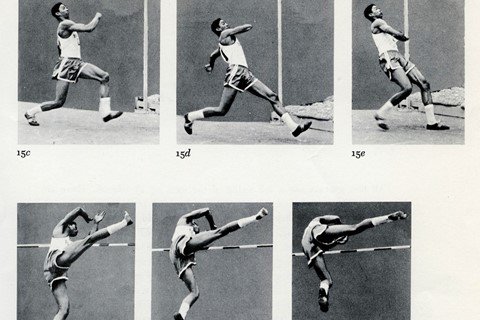

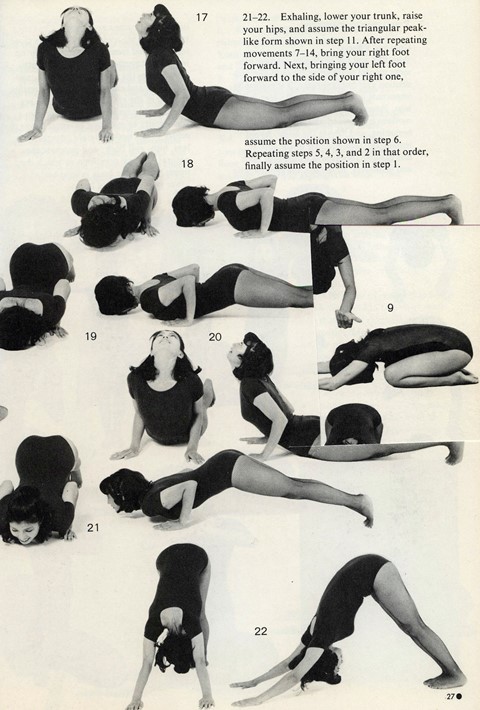

Winant’s book attests to compositional continuities, too. Following after Edward Muybridge, many instructional images are sequenced across a single plane in fragmented movements, becoming what Winant calls a “decentralised image”. And even when Winant dices them up, she doesn’t see them as stand-alone, “hero” images, but rather as constituents of a larger body. “My eyes pass and pause over my studio wall as I write, revisiting instructional images removed from books,” she reflects. “Because they are not – on their face – about the subject on the page as much as conveying information to the subject beyond it, I am met, anew, with the challenge to dissolve (or at least decouple) my ego from my artwork.”

Speaking last year at an online MoMA forum entitled What Does the World Look Like in 2020?, Winant observed: “There is, of course, an implicit power structure built into instructions. Who proffers the knowledge and who receives it?” While instructional images might indeed be a window dressing for elites to monetise the “right way” of doing things, Winant is interested in the ways that social movements – from the women’s liberation to Occupy and Black Lives Matter – have “necessarily destabilised this implicit hierarchy, decentralising the authority figure and restaging instructions as something mutual; something that reflects a reciprocal exchange of resources about our bodies and systems that they hold up.”

Cutting and pasting – which has long been a political tool in the feminist inventory, from Hannah Hoch’s androgenous figurines to Justine Kurland’s women-only utopias – is perhaps, then, an ideal vehicle for decentralising, re-learning and resisting. In Winant’s monumental My Birth (2018), she collated hundreds of photographs of women – including herself – in labour. Origins are, though less overt, an equally profound theme in Winant’s book, which ultimately probes the ways the “world of images” can facilitate a return to that which we have in common: our own selves. “It is all there, laid out for me on the page across dozens of photographs and staged by a body double,” Winant writes. “This is part of their charge. These pictures look outward – toward us, their incipient readers – and expect their gaze to be met, if remade, in return.”

There is no emblem more fitting than the mirror, which recurs over and over again in Winant’s book. “Wasn’t it Tolstoy who wrote that the mirror could also be a portal?” she asks rhetorically. “Wasn’t it Sylvia Plath who wrote that mirrors see us back?” In the penultimate passage, Winant recalls how, in one image, she found a woman who caused her to double-take: “Is this me?” she pondered. Even Winant’s children misrecognised the woman as their mother. We never see the image, for Winant lost it. However, she writes that her pain is lessened by the knowledge that she can always meet her double by looking into the mirror. Perhaps this is the ultimate instruction: trusting the image. After all, seeing – as the cliché goes – is believing. But believing is also seeing.

Instructional Photography: Learning How to Live Now by Carmen Winant is available via SPBH Editions.