Much like her singular approach to filmmaking, Sofia Coppola’s first book feels incredibly personal. The weighty, 480-page Mack-published tome blends the considered storytelling of a memoir with the DIY collaging of a teenage girl’s scrapbook, mapping a path from The Virgin Suicides through to her upcoming biopic on Elvis Presley’s ex-wife, Priscilla. Delving into a dense archive of photographs, annotated scripts and artistic references, it provides a rare insight into the making of Coppola’s unmistakable worlds and the complex female narratives which they sensitively parse out. “Across all my films, there is a common quality: there is always a world and there is always a girl trying to navigate it,” she tells journalist Lynn Hirschberg in Archive’s introduction. “That’s the story that will always intrigue me.”

Those who love Coppola’s films will know that a great number of influences have shaped her specific visual language, one which tells entrancing stories of transformation, privilege, youth and selfhood. Beyond being born into a family of influence in film, as the daughter of The Godfather director Francis Ford Coppola, a background in fashion and photography has equipped Coppola with an artillery of references which she has consistently drawn upon to create the visual splendour of her bittersweet films. These are artists who have stirred something in her personally over the years, from Hiromix to William Eggleston, Guy Bourdin and Jo Ann Callis.

Here, as Archive is released, we unpack the artistic works which have inspired Coppola’s dreamy cinematic universe.

The Virgin Suicides, 1999

Based on the 1993 novel by Jeffrey Eugenides, Coppola’s debut film is arguably her most visually gorgeous. Scored by a woozy soundtrack from French electronic band Air, it tells a tale of girlhood joy and sadness in 1970s suburbia through the lives of the five mysterious Lisbon sisters. Coppola drew upon several artistic references to bring its pastel-shaded world to life, but two photographers were particularly pivotal in its making: the first is prolific image-maker Tina Barney, who spent four decades capturing the domestic rituals of family life in America; and the second is photojournalist Bill Owens, whose book Suburbia Coppola returned to throughout the film’s production.

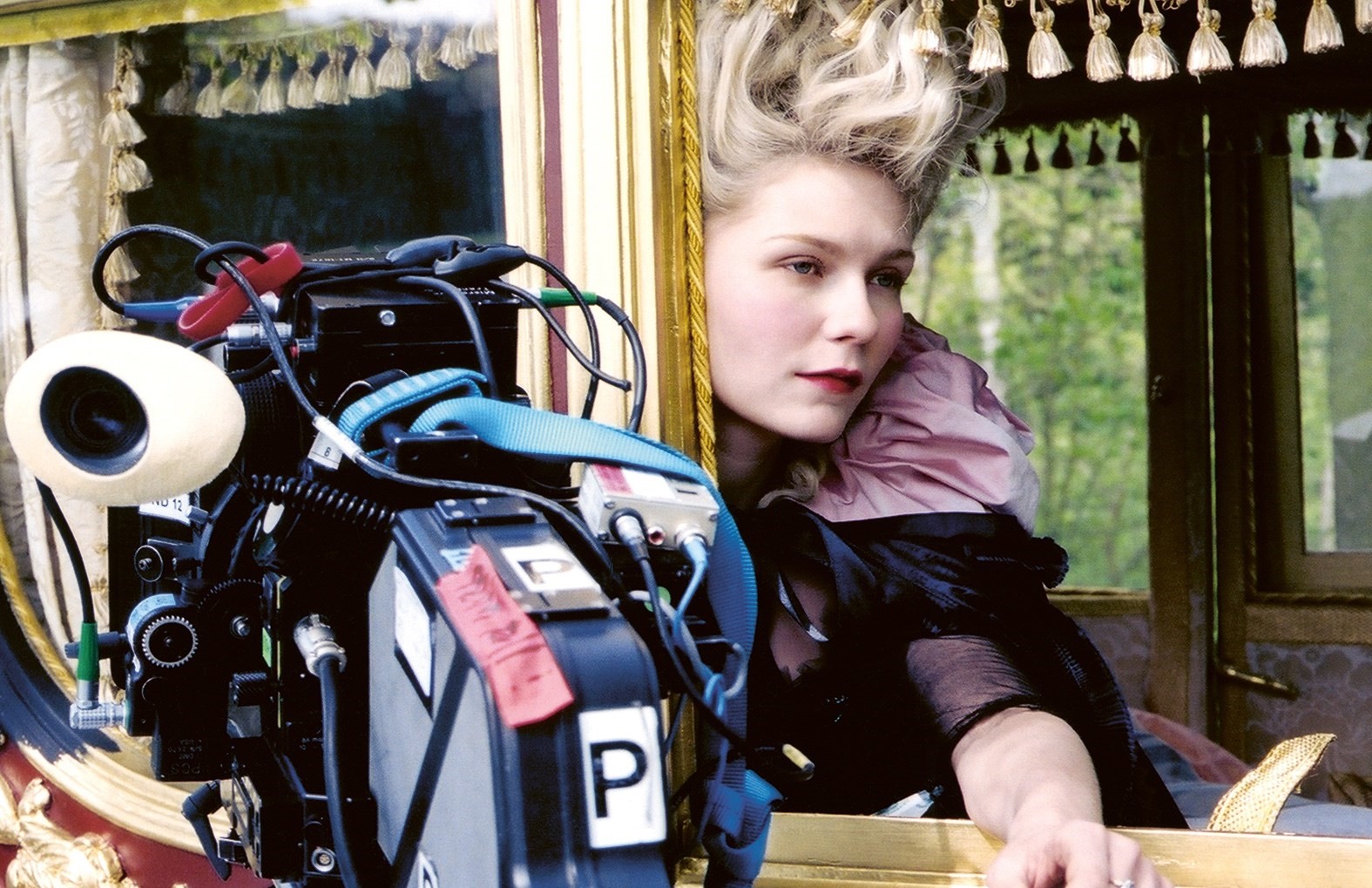

Coppola first encountered Owens’ work at an art fair she visited with her mum, who bought her a 1973 photographic print of two teens slow dancing at prom, titled Eighth Grade Dance. Capturing the headiness of young romance, it’s spirit is felt in the glittery, peach schnapps-fuelled scenes of the film’s fateful homecoming dance, before Lux (Kirsten Dunst) and Trip Fontane (Josh Hartnett)’s relationship inexplicably falls apart. Superfans will know that Coppola also invited legendary British photographer Corinne Day to take pictures on set; the resulting images still circulate the internet today. “It’s about the private world of girls,” Coppola says of the film in Archive. “I didn’t know I wanted to be a director until I read The Virgin Suicides and saw so clearly how it had to be done.”

Lost in Translation, 2003

Next, Coppola went about making her first original screenplay, Lost in Translation, a feature which would attract Academy recognition and cement her status as a gifted filmmaker in her own right. Set in Tokyo, the story of unlikely friendship between two lonely Americans – fading filmstar (Bill Murray) and an equally lost 20-something college grad (Scarlett Johansson) – was shaped by Coppola’s own searching trips to the Japanese city in her twenties. It’s a place where she observed that “girl culture was dominant”, and where she befriended Hysteric Glamour designer Nobu Kitamura, worked with Kim Gordon and Daisy Von Furth on projects for X-Girl, and met trailblazing photographer Hiromix, whose irreverent portraits of young womanhood in Japan would make a huge impression on the filmmaker.

With these inspirations swirling in Coppola’s mind, Lost in Translation was written while listening to Japanese dream pop and My Bloody Valentine’s angsty album Loveless, all the while daydreaming about meeting Bill Murray at Tokyo’s Park Hyatt hotel and confiding her own life struggles to him. But perhaps the most famous artistic reference in the film is seen in its divisive opening shot, which captures protagonist Charlotte in her underwear in bed turned away from the camera. Misjudged by some critics as objectifying, it directly references the sultry paintings of John Kacere, whose photorealistic works depict the midsection of the female body, usually dressed in lace underwear and silk bedclothes.

Marie Antoinette, 2006

Off the back of the blazing success of Lost in Translation, Coppola seized the opportunity to go big. Presenting a sorbet-hued spectacle of period opulence – shot in the Palace of Versailles with a crew of 100 people – Marie Antoinette traces the last queen of France’s teenage years in the lead up to the French Revolution. The story is, however, chiefly about a young woman making her own way in a family of prominence, and in many ways Coppola quietly saw it as a kind of self-portrait, having always felt like she had to step out of the shadow of her father. She drew upon many personal references to bring the feature to life, from the pomp and panniers of John Galliano to the stylings of the New Romantics, who soundtracked her own teenage years.

The film’s opening, set to the thrashing energy of Natural’s Not in It by Gang of Four, was inspired by a photograph of a woman lying on a silken chair with a maid at her feet, shot by legendary French fashion photographer Guy Bourdin. The decadent film, much like Bourdin’s provocative work, divided audiences when it was first released, but has since gained canon status. “It’s good to remember that sometimes things don’t land well at first,” Coppola says in Archive. “I always think it’s good to follow your heart.”

The Bling Ring, 2013

The least beautiful or romantic of all of her films, The Bling Ring in many ways marked a departure from Coppola’s earlier works. Set in the 2010s at the start of the social media boom, it saw Coppola shoot digital instead of analogue as it suited the story more: a greedy tale of teens robbing the homes of celebrities, inspired by real-life events which she first read about in an article in Vanity Fair. Shot in dark nightclubs and the real wardrobes of celebrities like Paris Hilton – one victim of the robberies – the look, Coppola remembers, had to be “lurid and oppressive for the story to work.”

Ironically, one image which inspired the film is a beautiful black and white photograph of Marilyn Monroe getting ready to go to the theatre, shot by Ed Feingersh in 1955. Holding a bottle of Chanel No.5, the image possesses an untouchable sort of glamour, status and celebrity – elusive qualities which the teen robbers in the film are trying desperately to get a piece of. “I always like a story about a kid trying to fit in with a glamorous crowd,” says Coppola. “To me, The Bling Ring was a cautionary tale … There was something changing and it was interesting to look at that: it seemed so different to what we grew up with.”

The Beguiled, 2017

Following The Bling Ring, Coppola said she needed to “cleanse” herself from “such a tacky, ugly world”. Her antidote to this was The Beguiled, a dark psychosexual thriller set in the American south during the Civil War, starring Colin Farrell as a wounded soldier who is taken in by a school of women – Nicole Kidman, Kirsten Dunst and Elle Fanning – and violence unfolds. Chilling and beautifully staged, it’s based on Thomas P Cullinan’s 1996 book but instead told through the perspectives of the female characters. Coppola “wanted the film to represent an exaggerated version of all the ways women were traditionally raised there just to be lovely and cater to men … and how they change when the men go away”.

Film stills from Gone with the Wind and Picnic at Hanging Rock populated the corseted, frilly moodboards which Coppola kept on set for the film’s cast and crew to look at, but the unsettling work of visual artist Jo Ann Callis was a direct inspiration for the film’s tense psychological world. In particular, a strange portrait of a girl in a lacy top with her head thrown back, so only her neck and shoulders are visible, was a key reference. “I feel like I always go back to this photo,” Coppola writes in Archive. “It fits the feeling in The Beguiled of frustration and being trapped in ultra-femininity.”

Priscilla, 2023

Set to hit box offices in October, Archive also provides a fascinating sneak peek into the making of Coppola’s latest story, Priscilla. Based on the 1985 memoir Elvis and Me by the ex-wife of the legendary musician, Priscilla Presley, the film is set to star Cailee Spaeny and Jacob Elordi. Like Coppola’s other features, it centres around themes of womanhood in extraordinary circumstances and the shape-shifting years of adolescence. Coppola describes it as Marie Antoinette set in Graceland.

Alongside incredible images of the couple from Presley’s archive – a flurry of beehived hair, eyeliner and bedazzled leather – Coppola looked to the photographs of William Eggleston for inspiration, whose rich and cinematic shots of the American south earned him the moniker of ‘the father of colour photography.’ In researching the film, Coppola unearthed a vivid series of images he shot of Graceland commissioned for a brochure in the 1980s. “I am always fascinated by transformation, and Elvis gave Priscilla a complete makeover,” Coppola writes of the film. “A Catholic schoolgirl by day and his beautiful creation at night.”

Archive by Sofia Coppola is published by Mack and is out now.