This article is published as part of our #CultureIsNotCancelled campaign:

In the winter of 2015, the art magazine Frieze asked British writer and critic Olivia Laing to write a regular column. She chose the title ‘Funny Weather’. “I was imagining weather reports sent from the road, my primary address at the time, and because I had a feeling that the political weather, already erratic, was only going to get weirder,” she recalls in the foreword of her new book, Funny Weather: Art in an Emergency, which collates these columns alongside essays written by Laing during the 2010s. “Though I by no means predicted the particular storms ahead.”

Storms, indeed. In the latter half of that decade, the world churned in an endless news cycle: Britain voted to exit the European Union, Donald Trump was elected as President of the United States, there were terrorist attacks and wars, the latter leaving streams of refugees seeking new homes where theirs had been destroyed. Atop all this, the vicious energies of nationalism percolated: Laing writes in Funny Weather of one image she can’t quite shake, “Nigel Farage with his sad beery smile, posing next to a truck displaying a photograph of young men in hoods and hats, walking across a damp green landscape. BREAKING POINT, the caption said.”

How does art fit within this frenetic narrative? Can it? Art – in a broad sense – is Laing’s subject matter. She started by writing about books, reviewing other people’s for The Observer; then, after losing her job in the 2008 financial crisis, Laing wrote her own. Titled To the River: A Journey Beneath the Surface, the book documents her walk along the length of the Ouse river in Sussex, in which Virginia Woolf weighed her body down with rocks, taking her life. Part-memoir, part-meditation on nature, what rises to the surface is the continuing power of Woolf’s words – her art – to illuminate and transform. It hardly matters Laing was writing nearly a century on.

In The Lonely City: Adventures in the Art of Being Alone – her third, and breakout, book – art has lessons to teach, too. Possessed by loneliness after moving to New York, Laing writes of the artists who turned this detachment from the world into art, among them Edward Hopper, Andy Warhol, Henry Darger and David Wojnarowicz. Here, art proves consoling, a way to help puzzle over how to live when we aren’t connected to other human beings. Wojnarowicz – an American artist who created polemical works during the Aids epidemic in New York to which he would eventually succumb – she writes, “did more than anything to release me from the burden of feeling that in my solitude I was shamefully alone”.

Like these, Funny Weather – which spans columns, essays, reviews and interviews, encompassing artists, performers and writers – is an assertion that art is necessary. “We’re so often told that art can’t really change anything. But I think it can,” Laing writes. “It shapes our ethical landscapes; it opens us to the interior lives of others. It is a training ground for possibility. It makes plain inequalities, and it offers other ways of living. Don’t you want it, to be impregnate with all that light? And what will happen if you are?”

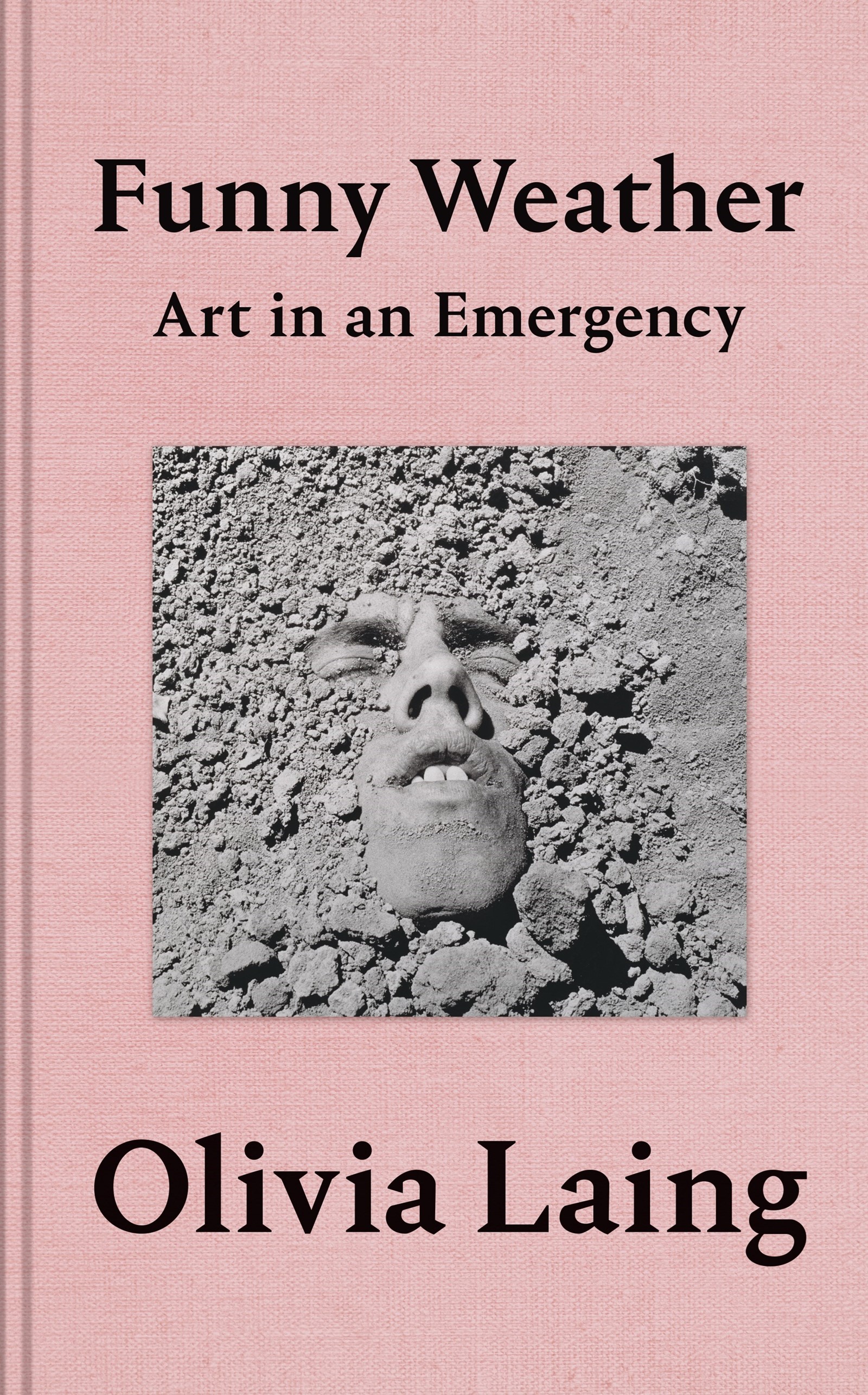

Wojnarowicz – a talisman of sorts for Laing, revisited once again in Funny Weather – appears on the cover of the book, his face half-buried in the Mojave desert dirt of Death Valley, California. It was taken just a year prior to his death and printed posthumously. His body was already suffering; travelling from New York, he called it his “last trip”. A month or so later, facing death, he writes in his diary that he “was trying to understand everything in the world”. Why make art in an emergency? Wojnarowicz, for Laing, makes it abundantly clear. This is “an image of defiance in the face of extinction,” she writes in Funny Weather. “If silence equals death, he taught us, then art equals language equals life.” This could well be the motto for any of the artists who appear in the pages of Funny Weather.

Here, as part of our #CultureIsNotCancelled campaign, which celebrates culture in an age of social distancing – and on the day of Funny Weather’s release – I talk to Laing about isolation, loneliness, and why art remains crucial to the way we see the world.

Jack Moss: I wonder if you could begin by telling me about how this book first came about? Why did it feel like the right time to collate these columns and essays?

Olivia Laing: I had the idea over the Christmas holidays in 2018. I was thinking about the theme of art in an emergency in the columns, and then it struck me that it ran through many of the essays I’d written in the last decade. It felt like it was a frightening time – though not as frightening as now – and I wanted to put together stories of art as a source of power, resistance, inspiration, waywardness, as a kind of antidote to anxiety and despair. I’d just published Crudo, which felt like a portrait of terror and instability, and I wanted to put together something that felt more sustaining, too.

JM: The sub-title of Funny Weather is ‘Art in an Emergency’ – the various artists, writers and musicians you discuss in the book have often faced personal crises, or operate at the margins. Why do you think this idea of crisis – and the creative potential that can entail – has become such a prescient theme within your work?

OL: I guess I’m quite drawn to artists from traumatic backgrounds, and interested in art as a way of responding to trauma. I grew up in a queer, alcoholic family, and I’m also really interested in how trauma is political. As to prescience, I say in the introduction to Funny Weather that I felt strongly when I started writing the columns that the times were changing for the worse, but that I had no idea of the events ahead, meaning Brexit and Trump. I also had no notion that the book would be coming out in a global emergency of this magnitude. That said, in my twenties I was an environmental activist, and the looming, oncoming catastrophe of climate change has always felt vivid to me. I think in a way I’m always writing into that feeling of limited time.

JM: There are some artists that have proved definitive and appear often in your writing, I’m thinking particularly of David Wojnarowicz – whose image, and face, appears on the cover – and Derek Jarman, whose Modern Nature you’ve said is one of your favourite books. How important is a personal connection to an artist’s work when you are writing? And why do you think certain artists resonate with you?

OL: I’ve definitely written about artists I don’t much like as people, including Hemingway and Hopper, but I prefer to write about people I love. Excitement and attraction are stimulating forces, and some artists – Wojnarowicz, Jarman and also Woolf – feel almost talismanic in their richness. I can return to them in any situation and discover something new.

“I think in a way I’m always writing into that feeling of limited time” – Olivia Laing

JM: In terms of the selection process, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s essay about paranoid/reparative reading is outlined as a kind of guiding principle for Funny Weather. It’s not an easy theory to summarise – but I wonder if you could just say a bit about what drew you to it, and how it plays into your own writing?

OL: Sedgwick! She’s so brilliant, and that essay is so apposite right now. It was written during the Aids crisis and it’s about how there are two ways of reading the world. One is paranoia, which means being concerned by and defended against the bad surprises of the future. It’s very much the dominant mode of the present moment, and especially of Twitter. But what Sedgwick points out is that paranoia doesn’t actually protect you. Knowing everything about No Deal Brexit, say, didn’t help anyone to prepare for the crisis we’re actually in. The other mode of being is reparative, which means creating something new and more sustaining out of the conditions of the present. What’s so powerful is that she points out there is always a choice, even in very grave or bleak times. The best example of the reparative I can think of is Derek Jarman’s garden. He made it during the Aids era, shortly after he’d received what was then an almost-certain death sentence, as his friends and community were dying around him. The garden is an expression of hope, a flamboyant manifestation of fertility and love in the midst of grief and despair. It’s not a substitute for activism, or a way of evading reality. It’s an act of survival in its own right.

JM: There is a really powerful bit at end of the chapter on Philip Guston, in which he talks about the small group of people who escaped Treblinka: “Imagine what a process it was to unnumb yourself to see it totally and to bear witness ... that’s the only reason to be an artist: to escape, to bear witness to this” – and you write, “He didn’t mean escape as in run away from reality. He meant act. He meant unspring the trap. He meant cut through the wire.” This feels in some way to be at the heart of all the artists you cover in the book. Why do you think art, and the artist, remains crucial to the way we see and witness the world?

OL: That’s a really good question. Art is about paying attention to reality. I don’t mean realism, or that art has to reproduce reality is a recognisable form. I mean it’s a technology that humans have developed over centuries – millennia even – for thinking through the conditions of their lives, for handling painful materials and for generating new ideas and new ways of being.

JM: You write in the John Berger chapter of his writing: “art criticism is rarely this plain, this fruitful, or this adamant that what happens on a canvas has a bearing on our human lives”. Is this a kind of principle of your own criticism too?

OL: Absolutely 100 per cent yes.

JM: Is there an essay in the book that’s particularly resonant, or important, to you?

OL: I really like the essay about women alcoholics, Jean Rhys and Patricia Highsmith and so on. I sort of wish I’d written that book instead of The Trip to Echo Spring, which was about men. These brilliant, extraordinary women, working in such punishing conditions. It’s a completely different story, much more political and much more interesting.

JM: There is a thread of isolation in the book, too – Agnes Martin and Georgia O’Keeffe both escaping to the desert, and yourself too, in the essay about living alone. Obviously isolation is a word that everybody is talking about at the moment. Is there something to learn from isolation?

OL: Yes, I think isolation, loneliness can be a very special place, as Dennis Wilson once sang. It’s painful, but it’s often a spur for creativity too. One of the things I really wanted to get to grips with in The Lonely City was how loneliness occurs because of marginalisation or stigma. We’re really seeing now that anyone can be lonely, that it’s circumstantial. It can be very frightening, but one of the remarkable things about loneliness is that feeling and sensation become almost painfully sharp. The world impresses itself on us in a very intense way.

“I think isolation, loneliness can be a very special place, as Dennis Wilson once sang. It’s painful, but it’s often a spur for creativity too” – Olivia Laing

JM: What are some of the ways you are getting through self-isolation now? Are you still writing? How are you staying calm?

OL: I wouldn’t say I’m totally calm, but I’m on a tight deadline to hand in edits on my new book, so I’m writing a lot, and doing a lot of interviews about how to survive loneliness, especially for Spanish papers. In the spaces in between I’m prowling around in my garden, tending tomato seeds and watching newts lay eggs. My husband is over 70, so it’s an anxious time, but it could be far, far worse.

JM: Is there a particular book you might recommend people read, or an artist they seek out?

OL: I always bang on about Modern Nature, but it’s literally about surviving a plague, so it feels more timely than ever. I also very much recommend the trans performance artist Mx Justin Vivian Bond, who has been putting on fantastic isolation performances via Instagram and YouTube. Please don’t miss Thursday happy hour at 10pm with Auntie Glam.

JM: On a positive note, the fund to save Derek Jarman’s cottage was raised – as someone who has become so entwined with his work and the campaign to save the cottage, how did that feel?

OL: Fucking amazing! Good news, thank God. I bit my nails all through the last day, when Alice at the Art Fund emailed to say they’d made it I burst into tears.

JM: Finally, what are you working on next?

OL: I’m in the final stages of a book about bodies and freedom that I’ve been working on for the last five years. Everybody will be out next year. It’s about the forces that can make embodiment a prison – violence, illness, discrimination – and it’s also about the body as a force that can change the world. The cast is very exciting: Ana Mendieta, Nina Simone, Malcolm X, Andrea Dworkin, Susan Sontag, Kathy Acker.

Funny Weather: Art in an Emergency by Olivia Laing, published by Picador, is out now.