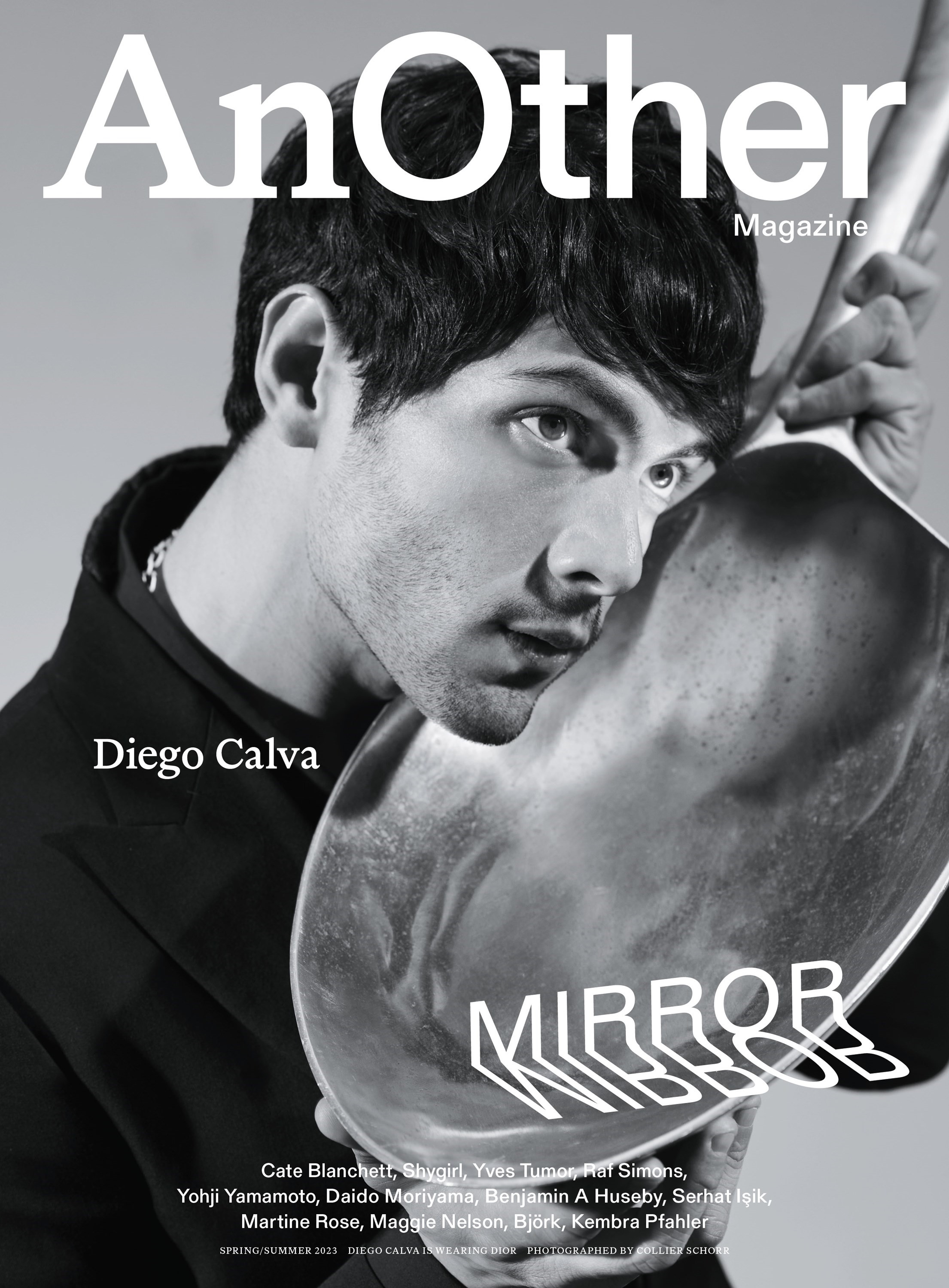

This article is taken from the Spring/Summer 2023 issue of AnOther Magazine:

Before the advent of sound swung a wrecking ball through the silent-movie era, actors relied on their eyes: Greta Garbo’s secretly amused gaze or Buster Keaton’s thundercloud stare could fill a page of dialogue.

La La Land director Damien Chazelle wanted a face with similarly deep waters for Babylon, his fable of success, excess and slippery morals in 1920s Hollywood. Shuffling through a stack of headshots one day, he found what he was looking for: a pair of eyes as eloquent as any from that halcyon age of movie-making. At the time, Diego Calva was living in an apartment in downtown Mexico City with no inkling he was on the verge of Hollywood stardom.

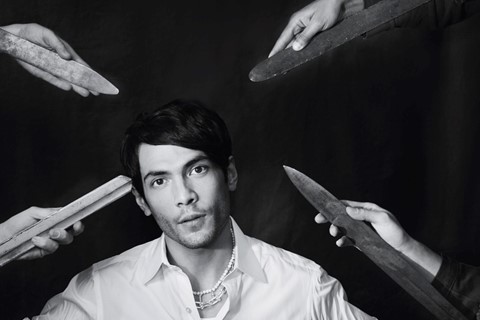

Calva had never shot an American film, never acted in English and definitely never been chased by 300 extras across the Californian desert with co-stars including llamas, camels, Brad Pitt and Margot Robbie. That scene from Chazelle’s $80 million extravaganza – the filming of a historical epic for which Calva’s character has to corral hundreds of Skid Row junkies into medieval battle gear before the magic-hour light seeps away – was his first day on a Hollywood set. Prior to that madcap initiation, Calva had self-taped more than 30 auditions, Zoomed with the director multiple times and finally delivered an explosive read-through with Robbie in Chazelle’s back garden that clinched the deal; the director compared their chemistry to Faye Dunaway and Warren Beatty’s. The morning we meet – Calva in a pale-green sweater, his lucky chain around his neck – the 31-year-old has just been nominated for a Golden Globe for his portrayal of Manuel “Manny” Torres, an immigrant dreamer hoping to break into Hollywood. Listed in a category with Daniel Craig, Ralph Fiennes, Adam Driver and Colin Farrell, Calva has done just that.

“This is one of those stories you never think will happen,” he begins, installed in the still-novel habitat of a five-star Manhattan hotel suite, a perk of his recently upended life that hasn’t lessened his humility and easy-going charm. “All the shock and surprise you see on my character’s face in those first takes is real. I was literally freaking out.” Babylon straddles the seismic transition to talkies that shifted the ground beneath the silent era. Los Angeles is still rising out of the orange groves, Bel Air is a patch of dusty bean fields and Hollywood a decadent, ramshackle colony populated by actors, gangsters, bootleggers and occultists. As Kenneth Anger wrote in his embroidered tale of scandal, suicide and soul-selling, Hollywood Babylon: “It was a time when Joseph Urban boudoirs were soaked in Shalimar, when $3,000 Parisian beaded gowns lasted the life of one party”. The salacious anecdotes and doomed stars of Anger’s Babylon wind their way through Chazelle’s. Its mammoth cast includes Pitt as a fading, John Gilbert-esque matinee idol teetering towards oblivion with a gin rickey in hand; Robbie as a Clara Bow-inspired ingenue running from a grim childhood into drug and gambling addictions; and a galaxy of supporting players that encompasses a poisonous gossip columnist, an ether-drinking mobster with a sex dungeon, and a parasitic on-set drug dealer (“Reds chill her out, blues keep her skinny”). There is rattlesnake wrestling, alligator wrangling and one hard-to-forget cameo from an elephant.

But amid the cinematic fireworks – and despite initial publicity that focused on Pitt – it’s Calva who occupies the film’s heart, as he rises up the Hollywood food chain from fixer in an ill-fitting tux to shellacked studio executive. The unravelling mayhem unfolds through his articulate eyes, most memorably at a Boschian orgy in a hilltop mansion where his duties include ejecting an uninvited chicken and getting an overdosing starlet to hospital without spoiling the celebratory mood. For the wide-eyed actor, who had never been to Los Angeles before, let alone hung out with some of the industry’s most glittering names, the lines between fiction and reality, himself and his character, were muddied beyond recognition: “When I started trying to be part of the movie business, I went in so many different directions,” he says. “I tried to be a boom operator, I worked in catering, I worked as a PA, I worked in the camera department ... So playing a character who is trying to get into movies, who’s going to a Hollywood party for the first time, like me, meeting Brad Pitt for the first time, like me – it was so metafictional I feel weird talking about it.” Although he and his character were born a century apart, Calva still has what he calls “Manny moments” that short-circuit his day, for better and worse. “Like, I’ll be walking in Beverly Hills and somebody will confuse me with the valet-parking attendant. Or at a restaurant somebody will try to order a drink from me and I think, ‘This is such a Manny moment.’ Then 20 minutes later I’m on the phone to Margot Robbie saying, ‘See you on the jet.’ I think, ‘What the fuck did you just say, Diego?’ The difference between the conversations I was having two years ago and now ... ” He gives his head a shake of disbelief.

There’s a coke-fuelled scene in Babylon in which a speed-talking Manny eulogises the movies in words that could easily be Calva’s own – since boyhood he has been equally in love with film. The only child of a publisher mother, he was raised in a book-filled apartment in Mexico City. “I grew up with only my mother for many years – my father is not my blood father,” he says. “My first years I just remember my mother working – I learnt how to walk in her office. Movies were my first babysitters. She showed me how to rewind and play the Disney films we had on VHS.” It was the wolf, all glowing eyes and dripping fangs, in the animation Peter and the Wolf that first captivated his nascent imagination. “I remember being so scared, but wanting to relive that feeling again and again,” he says. “That was the moment I discovered that this weird screen could make me feel so many emotions.” His apartment became the site of impromptu plays, staged by Calva and his best friend Bruno for neighbours in their building – five pesos a head. At school he signed up to improvisation workshops and at weekends his grandparents took him to the cinema, whispering the salient plot points in his ear before he learnt to read subtitles. As he got older, the rest of his free time was spent skating the sprawling metropolis with a bunch of like-minded friends – he once broke a leg doing it. “I remember watching Kids, written by Harmony Korine, and thinking that was my life documentary,” he says with a laugh. “I’m from that generation before social media, so I spent most of my days on the street.”

He saw his home turf with new eyes after discovering Luis Buñuel’s 1950 masterpiece Los Olvidados, an unflinching portrait of teen delinquents scratching a living on the rackety edges of Mexico City: “I remember falling in love with my city again, you know? I just wanted to be on these streets and record everything.” Taken by his mother to Cineteca Nacional, a jewel of an art cinema in the capital’s Xoco district, the visions of cinema’s original thinkers came as a jolt. “The first time I watched 8½, something changed. The first time I watched Jean-Paul Belmondo smoking and then wiping his lip in Breathless, something got into me,” he says. “Jonas Mekas, too, made me want to be a filmmaker, make video art, installations – anything.” Already writing stories and poetry (he and Bruno made a poetry zine together, selling it in carnicerias and dentist’s offices), he began making his own short films while volunteering on the sets of older friends and local filmmakers. Operating the boom for a short one day, a miniature star-is-born moment happened: an actor failed to show and Calva was asked to step in. It led to roles in a handful of other shorts, until in 2014 he heard about an audition for a feature that needed two leads who could skate. “The reference was something like ‘Los Olvidados on wheels’, so I was interested,” Calva remembers of Julio Hernández Cordón’s dark indie drama Te prometo anarquía (I Promise You Anarchy). “Then something very weird happened at the audition. I was waiting for my turn and started talking with the guy who had already been cast in the other role. We realised we both knew a good friend who got killed by the narcos. We started crying, because it was literally a month after his death. The director said, ‘Do you two know each other?’ We said, no, but we have a friend in common. He said, ‘OK, you don’t need to audition – Diego, if you want the role, you have it.’ And that’s how I got into movies. So sometimes it’s not about being in the right place at the right time. Maybe your bad moments, like spending a lot of time on the streets with sometimes sketchy people – it can lead to the most beautiful thing that can ever happen.”

With this first starring role, it was clear Calva could draw eyes towards him like iron filings to a magnet. Playing a gay skater running a black-market scam for a cartel, the actor pitched his character precariously between youth and adulthood, negotiating his burgeoning sexuality amid the machismo of the criminal underworld. His wheels grind along the freeways, fluorescent-lit back alleys and wide-open plazas of Mexico City, from strip clubs to skateparks to the insides of an abandoned propane tank slung with hammocks that doubles as a crash pad. The film was a festival hit, nominated for the Golden Leopard at Locarno and winning Calva the best actor award at the Havana Film Festival. It also brought the then 23-year-old his first bonafide pay cheque: “I was living in a small apartment with no windows at the time. I never had any idea if it was day or night,” he says. “I didn’t have a job, no money, I was in a tricky situation. Then I earned maybe $2,000 for that film, and I was like, ‘Mom, we’ve made it!’”

“Playing a character who is trying to get into movies, who’s going to a Hollywood party for the first time, like me, meeting Brad Pitt for the first time, like me – it was so metafictional I feel weird talking about it” – Diego Calva

Still, his focus remained behind the camera: he enrolled in the scriptwriting and directing course at Centro de Capacitación Cinematográfica (CCC) in Coyoacán, the bohemian district that was Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera’s old stomping ground. A film school proud of its avant-garde instincts, the CCC named Buñuel its honorary president when it was founded in 1975. “I already knew many people there, because before that I was the guy who wasn’t at the school but was hanging in the back all day anyway,” he says. Calva juggled his studies with parts in small but memorable arthouse Mexican and Argentinian films until the role of Sinaloa-born drug lord Arturo Beltrán Leyva in Narcos: Mexico put him in front of an international audience – he remembers noticing budgets had improved when the fake bullets in his gun were no longer rationed. Initially a lieutenant in El Chapo’s cartel, Beltrán Leyva was later one of the bloodier players in Mexico’s gory turf wars. But as infamous as he was, his backstory was so murky only a few blurry snaps of Beltrán Leyva exist, one from the grisly scene of his death in a shoot-out. “There’s no information about him at all, only police reports,” Calva says. “But in Mexico they have corridos, songs people write for these drug lords. I found out about his attitude from those songs – that he dressed in black, with chains. He had an SUV called El Satanica – Satan. There’s even a song about the white cowboy boots he always wore.” The lyrics, together with a slightly spooky anonymous tip, allowed Calva to jigsaw together an image he could build on. “Someone created a fake Instagram account and sent me a photo of a photo of Arturo when he was young, in a vest and boxers,” he says. “It’s the only photo we have of him when he was young. And then whoever he or she was deleted the account. That was fun ... A little dangerous, but whoever it was, thank you.”

The series’ brutally violent depiction of his country didn’t always sit well with the actor. Post-Narcos, he was mainly hoping for jobs that required fewer bullets. Instead he was blindsided by a call from the Oscar-winning director of La La Land and eventually landed in La La Land himself. Although the city is notorious for casually bulldozing its history – Rudolph Valentino’s Falcon Lair and the Pickford-Fairbanks studio included – when Calva touched down at LAX for the first time, he went in search of Babylon’s lost era of giant megaphones and sizzling klieg lights: Musso & Frank Grill, the Spanish-gothic United Artists movie palace downtown, Gloria Swanson’s one-time residence the Beverly Hills Hotel, and the Mack Sennett studio in Silver Lake, where Charlie Chaplin penguin-walked through his early comedies. “Those first days in LA, I could feel that idea of Babylon everywhere,” he says. “Just putting this city in the middle of a desert – you have to be a little crazy. There’s this story that when Buster Keaton told his dad he wanted to be an actor, his dad disowned him. Acting was considered such a low art, so vulgar then. I love the idea that they were all misfits.” Sifting through Tinseltown lore, he searched for true-life examples of his own character. “I tried to find a successful Mexican guy from the 1920s – it was hard,” he says. “There was the actor Ramon Novarro. But someone like Manuel, it’s one of those untold stories, I guess. So instead I focused on the Mexican communities during the 1920s and 1930s in Chavez Ravine. Now it’s Dodger Stadium, but 100 years ago there was a Mexican community there, until the police took them out with violence in the 1950s – it’s not a good story. But this guy, Don Normark, spent time photographing the people there, and that helped me imagine where Manuel was from.”

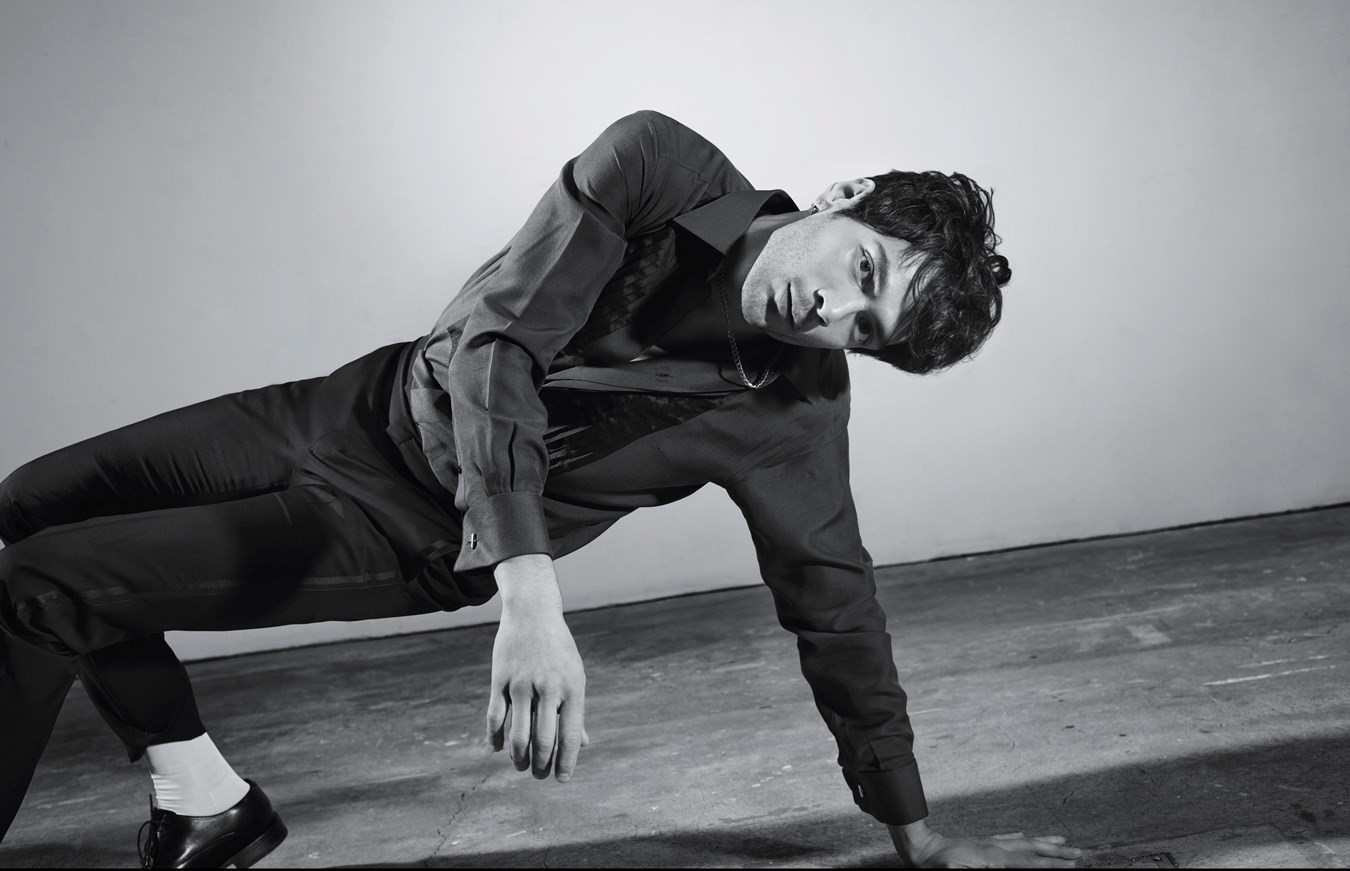

There were more practical preparations too: dialogue and acting coaches, a crash course to bolster Calva’s English (mostly gleaned from Pokémon video games and film subtitles until that point) and daily horse-riding and gun-range lessons in Griffith Park. In the evenings he studied the magic of Old Hollywood, above all Chaplin’s body language in the likes of City Lights and The Kid. Chazelle also pointed him to Al Pacino’s bravura performance in The Godfather – in Babylon, Calva’s character undergoes a Michael Corleone-style transformation from naive idealist to ruthless shark. “Manny’s an observer, always thinking, trying to solve situations, so you need to see the machinery,” Calva says. “Pacino can go from 0 to 100 in a second, but also he works with his eyes. The first time I arrived at Damien’s house, he had a suit for me, a groomer did my hair like the 1920s, and his wife, Olivia Hamilton, started circling around me playing The Godfather soundtrack.” Calva moved in with Chazelle for ten days while they enacted a lo-fi version of Babylon several times, Hamilton playing every other character while Chazelle filmed them on his mobile phone. “Damien wanted to see if I could be tough enough to act opposite Margot Robbie,” he says, “because if you back up a little, Margot is going to eat you, in the best way possible. She’s so committed to the character.” Chazelle needn’t have worried; the actors forged an instant connection, offscreen and on. “Diego would surprise me endlessly,” Robbie wrote to me. “The fact that he could improvise and be so funny or scary or heartbreaking was just remarkable. About 60 per cent of the movie plays on a close-up of Diego’s face. That’s for a reason: he can emote so much, just with his eyes. I’ve never seen anything like that.”

When Robbie realised the newcomer was spending evenings watching films alone in his hotel room, she invited Calva to stay with her, her husband Tom Ackerley and their menagerie of pets, including pit bull Belle. They played cards and walked the dog, defusing the high-octane adrenaline of the shoot with a comically prosaic domesticity. Pitt was supportive too, stepping in one day when the actor was struggling with a take. He encouraged Calva to tune out the noise and focus on what mattered: “He told me we actors have to protect our craft because everything else is an illusion. Fame, what is that? But your craft, what you’ve experienced and what you’ve learnt on the way, that’s yours and that’s the real treasure.”

By the time the three-hour-nine-minute opus wrapped, Calva had been living in its meticulously created universe for almost a year. “Even Damien and Brad and Margot say, ‘This is one of the hardest movies we’ve ever done.’ And I’m thinking, ‘This is my first Hollywood movie? Wow, I’m happy I survived.’” But unplugging had its own complications – he struggled to leave behind the character he had inhabited down to the 1920s-style suspenders on his socks. He still calls Manny his best friend. “Damien told me, travel the world while nobody recognises your face,” Calva says. “But I flew to Mexico for one day and went straight to Barcelona to shoot another film. I think I was afraid to have that empty-nest feeling.”

In the final moments of Babylon, Calva’s character, a little older, returns to Los Angeles, buys a cinema ticket and enters a darkened auditorium to watch an old movie starring the beloved ghosts of his past. The camera holds on his face as he watches the screen with a tangled rush of emotions. Months later, when Calva himself returned to the city to see Babylon in its entirety for the first time, he had a woozy moment of art mimicking life that drew a line under his surreal first chapter in Hollywood. “I watched it by myself in an empty studio in LA,” he says. “It was a rollercoaster. I cried. And in the final scene of the movie, it was like a mirror in a mirror in a mirror – me watching a movie of me watching a movie, and it was a beautiful end to the circle. That’s a memory I’m going to keep forever.”

On New Year’s Eve in Mexico, there’s a tradition of eating 12 grapes: 12 wishes for the 12 months ahead. This year, so many of Calva’s most improbable dreams had become reality that he found himself uncharacteristically wish-less. “Real life is like a movie!” he says. “I just want to be present right now.” Even the formidable schedule of morning newscasts and late-night talk shows, red carpet appearances and red-eye flights are yet to tire him. “It’s my first time and everything is so new,” he says, gesturing towards his view of downtown Manhattan. “I never stayed in five-star hotels before. I am still not bored with hotel food. I love minibars. I can get used to this.”

The Golden Globe was eventually won by Colin Farrell. But Calva’s critically feted performance is sure to bring him some previously unimaginable opportunities. His fantasy future collaborators are a cinephile’s list of auteurs, from Ruben Östlund and Leos Carax to Greta Gerwig and Noah Baumbach. At the same time, his roots in Mexico remain firmly tethered, despite the tornado of recent months. “Honestly, there are directors I studied with who are going to be incredible new voices,” he says. “I want to come back with this thing called ‘fame’ and try to support some of those projects. Mexico’s movie industry is growing every day and I love it.” And so for now, Calva will continue to live in and be inspired by the streets of the megalopolis he grew up in. It’s a grounding that chimes with a philosophy his mother instilled in him, along with her love of the arts. “My mother, she’s so wise,” he says. “She told me, it’s not about trying not to get crazy or get lost, because that is going to happen at some moments. But we have this phrase we say a lot during these days – just remember the way back home.”

Hair: Tamas Tuzes at L’Atelier NYC using R+CO. Skin: Jessica Ortiz at Kalpana using LA MER. Movement director: Angel Zinovieff. Set design: Javier Irigoyen at Lalaland Artists. Digital tech: Jarrod Turner. Lighting: Ari Sadok. Photographic assistants: Bernardo Gasparini and Romek Rasenas. Styling assistants: Bella Kavanagh, Jordan Duddy, Alexa Levine and Charlotte Ghesquiere. Set-design assistant: Jordan Mixon. Production: DAY INT. Post-production: TwoThreeTwo

This story features in the Spring/Summer 2023 issue of AnOther Magazine, which goes on sale internationally on 23 March 2023. Pre-order here.