It is widely assumed that class is a purely British obsession. Riccardo Tisci, appointed chief creative officer of Burberry in March last year, disagrees.

“It exists everywhere, baby,” he laughs. As a young boy of southern-Italian heritage, raised in the north of that country, it’s fair to say he has a deeper understanding of such things than many. At school, he and his siblings were labelled “terrone”, a term used by prosperous northerners to describe those from the less-affluent south, literally translating as ‘people of the earth’. Such distinctions, couched geographically in Britain’s own north-south divide, are in Italy simply reversed.

Still, “here, people see it more”, Tisci concedes. “It’s a look. You have punks, you have skinheads, you have the aristocracy, you have the Queen, who I love. It’s my dream to meet her. Did you see she wore the scarf?” He means a Burberry scarf, and she did indeed, stepping off the train for her annual Christmas break at Sandringham in December sporting that very accessory – checked no less – and looking especially fine. “Class is everywhere,” Tisci argues. “It’s in India, in China...”

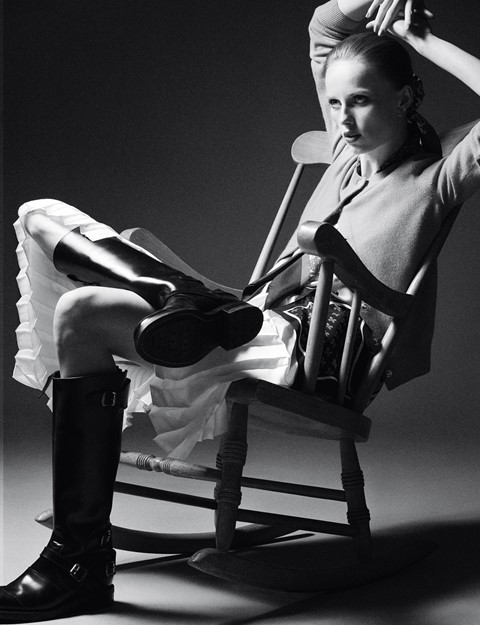

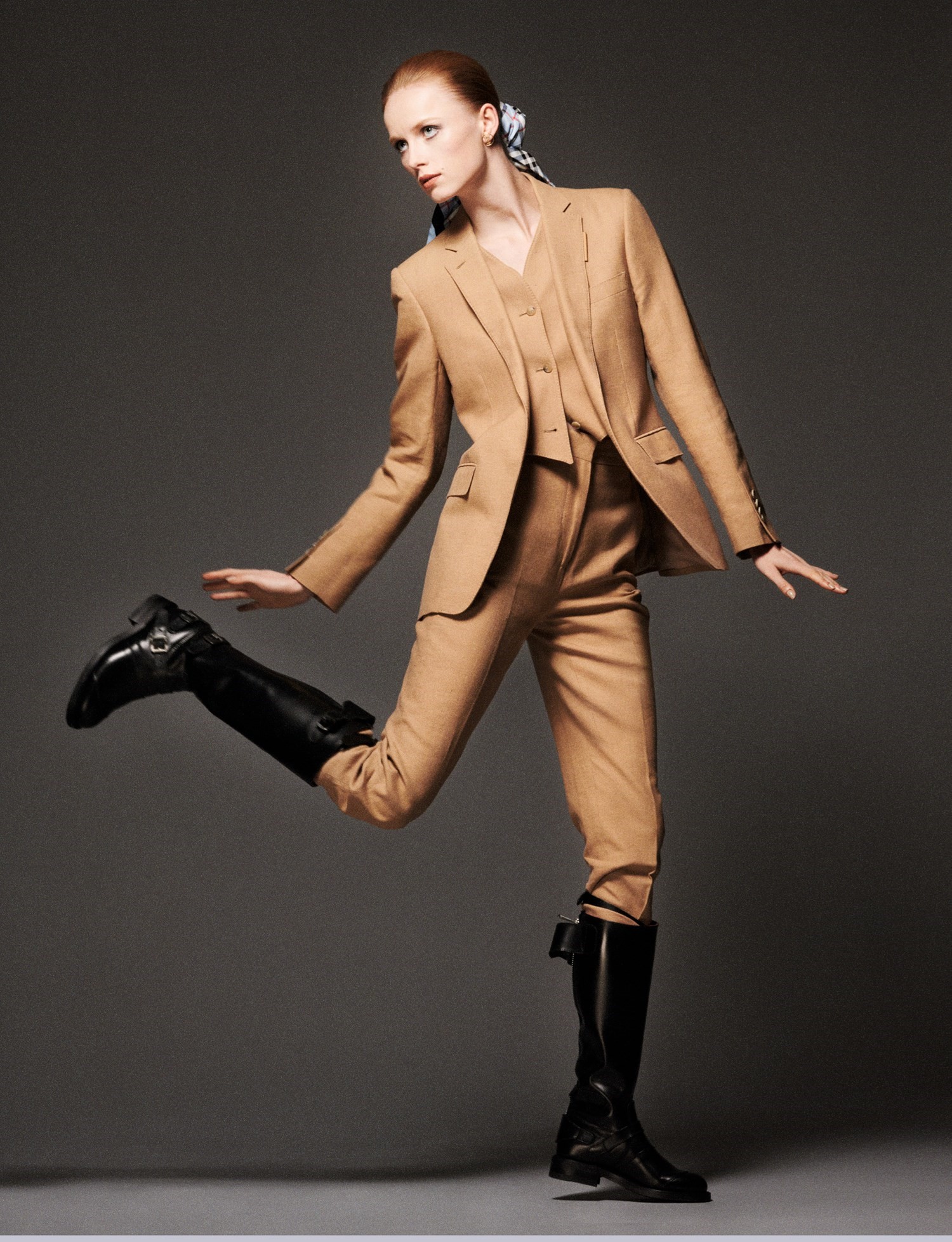

In England, though, class is especially pervasive: encompassing language, schooling, food, social mores – and, of course, clothes. That message was therefore not so much pivotal as unavoidable for the designer’s first runway collection for this label, shown in a Royal Mail depot in south London last September – it’s hard to imagine a location more distinctly British than that. Over and above any other luxury brand, Burberry is a name synonymous with England, with democracy on the one hand but acknowledged – worn and warranted – by royalty on the other. With that as a reference and with an Italianate sense of bravado, not to mention the thoroughly engaging idealism of an outsider looking in, Tisci neatly cleaved his ambitiously scaled 134-look presentation into an equally ambitious microcosm of English social strata. He dressed the princess at one end of the spectrum and the aforementioned punk at the other, addressing an Anglophile formality all while embracing anarchy. He called it Kingdom – unlike our own, Tisci’s was united.

For the sake of clarity, the show notes divided the collection into sections: “Refined: representing the formal, the refined, defining the more sartorial house codes reimagined through a contemporary lens... Relaxed: representing the more rebellious spirit of the UK inspired by the idea of journeys and freedom.” The final sequence was labelled ‘Evening’ – black gala dresses trimmed with bold bullion fringe. There is nothing more British than pomp and circumstance, after all.

And so, the opening was neat, even regal. Upscale separates, pussy-bow blouses and knee-length silk dresses were modelled by, among others, the blue-blooded Stella Tennant. Soon followed crepe-soled Mary Janes and slashed and sloganeering garments aimed squarely at the young and irreverent at heart. There were shades of the Eighties, casual in sporty outerwear for boys – Tisci, it is well known, understands this – and of City boys in sharp, manly suiting with its roots in Savile Row. In the end, referencing migrated: metal rings edged a classic trench coat, and bra and bondage details featured in further iterations of that same country-living garment. The idea of underwear as outerwear was notoriously championed by Dame Vivienne Westwood, a designer beloved by Tisci, as it turns out. And Tisci testifies to the fact that the trench forms at least part of the narrative around which the Burberry name was built. “It has its story in every country now, but its roots are here, in England, at Burberry – Burberry started that,” he says. Personally, however, he is a Montgomery man. He bought one years ago in Paris and has recently replaced it with a second. A duffle coat, more schoolboy that military in essence, “It’s just more me,” he says.

The designer moved from his home near Como in Italy as a teenager and studied fashion at Central Saint Martins, but his process in gathering inspiration for the show was still that of the tourist, albeit the enlightened tourist. “It was like collecting different things that represent England,” he explains. “I sent my team out into the street and asked them to take pictures of things, pictures of typically English things. It was nice. Then we made a list – the history of England, the evolution of the Victorian times, the street tribes. So it was all these strong images of England, pulled together to make an homage. Then we thought of typical words, like, sorry for the vulgarity, but one of the first phrases that I learnt when I came here was ‘fucking cow’.” Tisci smiles, wide. “That is really English. So is the word God – ‘Oh, God!’” As far as the latter is concerned, he was an early adopter. He uses the phrase often.

Surely enough, these elements, forensically collated, found their way onto clothing. Portraits of Victorian ladies and gentlemen were printed across silks and tailored trousers, fishnet veiled a polo shirt, the words SOCIETY and WONDERFUL were stamped on scarves. WHY DID THEY KILL BAMBI? was a direct nod to the Sex Pistols, I WEEP FOR JOY TO STAND UPON MY KINGDOM ONCE AGAIN, to Shakespeare’s Richard II. Blink and you might have missed these painstakingly sourced motifs, although COW writ large on a T-shirt work with a cow-print skirt made for quite some entrance. Then there were tabloid-newspaper headlines, passports worn as necklaces, Polaroids of airline departure boards, vintage cars, a unicorn... The list goes on.

“Putting all of this together, it is not a moment, it is a lifestyle, a history,” Tisci says. “And England has one of the greatest histories in the world. The English probably don’t want to talk about it, but you guys, right from the beginning to now, you revolutionised, you did so much. A British person can’t talk about that.” An Italian person apparently can. And Tisci did so with intelligence, respect and affection.

We meet at Horseferry House, Burberry’s headquarters and formerly a government building, next door to MI5 in Westminster, the day that Tisci returns from his Christmas break. At seven storeys, the space the company immediately moved into following the 2008 stock market crash is nothing if not impressive. It’s proof, if ever any were needed, of the sheer scale of the brand: Burberry remains the only British luxury label listed on the FTSE 100. In fact, there are only limited signifiers that there is a different creative at the helm today: the new – and great – TB monogram, designed by Peter Saville only months after Tisci’s arrival, is printed on panels on the walls; there is marginally more beige soft furnishing than there once was. “Beige is the colour of Burberry,” Tisci says. “I’m bringing it back.”

It’s early January, and he bounds in with coltish enthusiasm, even though, straight off a plane, he has a heavy cold. Riccardo Tisci is tall, handsome, very much in the Italian manner. Yet he is now a Londoner – after having lived here through his student years, and revisited often in between, the 44-year-old has been based here since shortly after his appointment was announced.

Tisci and I have known each other almost since the start of his career, and have met many times, both formally and informally. The conversation begins personally. “I had a fantastic Christmas with my family,” he says. They spent the holidays together in Paris, where he still has a home. “It was one of the most special of my life. This year was very tough for my mum. I nearly lost her in January. One of my sisters [he famously has eight] had some physical problems. The year before, another of my sister’s husband died. It’s been difficult. My family was like – how can I explain? – unstable.”

Prior to accepting the position at Burberry, Tisci took a sabbatical – something almost unprecedented, given the increasingly pressurised world he is part of. In February 2017, it was reported that he was leaving the French fashion house of Givenchy after a 12-year tenure. While the news was surprising, the split was clearly amicable. Bernard Arnault, CEO of LVMH (Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton), the luxury-goods conglomerate that owns the maison, had to say: “The chapter Riccardo Tisci has written with the house of Givenchy represents an incredible vision to sustain its continuous success, and I would like to warmly thank him for his core contribution.”

For his part, Tisci said: “I have a very special affection for the house of Givenchy and its beautiful teams. I want to thank the LVMH group and Monsieur Bernard Arnault for giving me the platform to express my creativity over the years. I now wish to focus on my personal interests and passions.”

It is true that Tisci had reversed the fortunes of Givenchy, bringing it back to both profitability and a position of key importance in global fashion. He left on a professional high; personally, though, things were more fraught.

“I took my sabbatical because, when I came to London when I was 17, I completely changed my life and the lives of another nine people, my mum and my sisters,” Tisci says. “I come from a very poor family. Everything went so fast and they were so proud of me, but the year before I left Givenchy, as I said, my sister’s husband died. I was at work in Paris, it was just before the haute couture, I took the flight to Como, I arrived at the funeral and saw everybody. I was late. I arrived the moment the body came into the church. I sat down and just looked around me. I saw my mum next to me looking frail, small, the kids growing, all my friends and everybody in the family, and I was just like, ‘No, that’s that.’ I went back to Paris and told them that I didn’t want to work anymore, that I wanted to stay with my family.

In an industry hardly famed for its humanity, this was an open display of just that. “And I’m so glad,” Tisci continues. “I think I gave my mum another ten years. Touch wood. Because I spent one year with her, doing normal things. Before that, I made my family happy financially, tried to go to Italy every Christmas and birthday, but to spend a real healthy 20 days together was not something I had done for a long time. So that was amazing.”

Riccardo Tisci was born in 1974 in Cermenate, a small town in the province of Como, in northern Italy, about 30km from Milan. “But my blood is from the south,” he says. His parents, Elmerinda and Francesco, met and married in Taranto, in Puglia, a city that the designer once described to me as “very dark, religious, processions, veils. There was a legend that mermaids are found swimming there”. The couple moved to and settled in the North and set about building a home for their family, which grew quickly. Tisci’s father made a decent living selling fruit imported from the south until, in 1978, he died suddenly, leaving his wife and children financially adrift. Riccardo was four years old.

While his schoolmates wore Emporio Armani, Tisci went to school in his sisters’ hand-me-downs. Often, they were pink. “Funny, though, because I never really suffered. My home was heaven. My mother was incredible. She never made us feel different, and I used to come home from school, play with my sisters, watch them getting dressed to go out. I was safe at home… happy.”

Studying by day, all the Tisci children worked after school to contribute to a household presided over by the matriarch who took care of them. Aged 12, Riccardo worked for his uncle, who was a plasterer. Typically, when not working, he shut himself in his room and listened to music. He loved The Cure. He paints a gothic figure: pale faced with long dark hair, absorbed in making collages, half-human half-animal, demonstrating creative talent that led to at least one of his teachers encouraging him to take on different work – at a florist, in a boutique – to earn more money to go to art college. It was the late Eighties and the Italian designer ready-to-wear industry was booming. Gianni Versace and Giorgio Armani were front-page news and the young man was captivated. Soon after, and encouraged by family and friends, he made his move. “Italy isn’t a country that helps young people. I had to go.”

He arrived in London, and studied first at the London College of Fashion and then Central Saint Martins. “I lived the life of England, which was fantastic for me,” he says today. “You know, income support, my apartment paid for. This country gave me the opportunity, even though my English was bad.” He still took on casual work – as a doorman at former high-street chain Mark One and as a shop assistant at Monsoon – and worked in the London studio of fellow Italian Antonio Berardi, all while making the most of the British capital’s burgeoning club scene. “It was craziness, you remember, insane. And you could be anything – anyone – that you wanted. If you wanted to go out in flip-flops, with a huge hat, with big hair, people just didn’t care.” He called his mother once a week – collect.

I point out that such assistance would not be offered to a fledgling designer of his background, however talented, now. “That’s true. Oh god, you’re giving me goosebumps – it wouldn’t happen now,” he says. “But still, it’s thanks to England that I am who I am. I never dreamt I could come here to study. The British love of freedom of expression brought me here. And I never for one second thought I would become what I have today.”

He makes it sound like plain sailing. That wasn’t the case. By the end of the Nineties, he was back in Italy, living in Milan, working for Puma, Coccapani and then the pioneering leather-goods brand Ruffo Research, but just as he was completing his first collection for that company, in the summer of 2004, it closed. And so the Riccardo Tisci label, darkly romantic, delicately gothic, was born, made by the designer at home, with the help of his mother and sisters, and shown off-schedule. It was a slow burn. Some press paid attention – few. Those who did are still ferociously loyal to Tisci, and vice versa. Gradually, orders came in. Riccardo Tisci was featured in French and British Vogue, in Dazed & Confused. Björk was his first famous client. His second collection, shown in a disused factory in the suburbs and based on the Lenten parades of Catholicism, was a breakthrough. Presented against a backdrop of a monolithic crucifix and modelled by Mariacarla Boscono – a dear friend whose face also appeared on the illustration for Tisci’s graduate collection invitation – and her contemporaries for free, it caused a sensation. The day after, Tisci says, aged just 30, he received a call from Marco Gobbetti, CEO of Givenchy, followed by Céline, and now Burberry, neatly enough. “Marco is the person who, when I was a little kid from Milan, brought me to Paris and gave me the chance. He gave me Givenchy, he was the one who fought with everybody to get me there. He’s like a father to me.”

The announcement that Tisci would take the helm of Givenchy was made on 28 February, less than a week after the show in question took place. Comparing his appointment to the Vittorio De Sica film Miracle in Milan – a fantasy tale about an orphan retrieved from a cabbage-patch – Cathy Horyn, fashion critic of The New York Times, described him as “the latest cabbage-patch discovery” in that paper. It was more the stuff of miracles than foundlings, however – an unknown designer had been handed the reins of a fashion house familiar to the world for billions of perfume bottles, and the legacy and incomparable chic of Audrey Hepburn. Many misspelled his first name (the easily missed double c), or were unable to pronounce his surname (it’s tee-shee). In July 2005, the designer showed his debut haute couture collection for the house, presented via a series of tableaux vivants in the hôtel particulier where the clothes were then made. With its strong interplay of black and white, masculine and feminine, leather and lace, Tisci’s signature juxtaposition of contrasting elements, of different ‘classes’ of clothes – then for Givenchy, and now beyond – was already laid out. “It’s so modern,” declared Carine Roitfeld, editor-in-chief of French Vogue, at the time. Looking back on it, it was – and still is.

At Givenchy, Tisci combined his own aesthetic with a certain French classicism that appealed to a new – modern and fashion savvy – customer. Just over five years after his arrival, the company broke even, and not long after that, moved into profit. Tisci’s menswear, in particular – comprising clothes more familiar to the street and to sportswear than to prêt-à-porter, including, most memorably, money-spinning sweatshirts emblazoned with rottweilers – sold. Staff tripled. Sales grew to a robust €500m per year. Tisci’s famous friends helped him on his way. Among them were Madonna, Marina Abramović, Courtney Love, Kim Kardashian West, Kanye West and Beyoncé Knowles.

Significantly, and perhaps as a result of his less-than-conventional upbringing, Tisci embraced otherness from the start, at Givenchy casting his childhood friend Lea T both on the runway and for a Givenchy Autumn/Winter 2010 print advertising campaign. He commissioned Antony Hegarty – now Anohni – to create a live soundtrack for his blockbuster Autumn/Winter 2013 womenswear show. This was long before such things were celebrated in fashion circles – and bourgeois French fashion circles in particular – or indeed outside of them, for that matter.

“Transgender for me has always been something normal,” Tisci says. “Lea used to be my assistant. Sometimes she used to go to the cemetery with my mum. She was a transsexual, taking my mum to the cemetery in a little village. People said nothing. Italian people may criticise but they never judge in a strong way. What I did – and I’m not saying it is good or bad or right or wrong – is maybe what society was missing at the time. That’s done now. That was my story, that was the past.”

Anyone expecting an all-singing, all-dancing, star-studded debut by Riccardo Tisci for Burberry – or indeed any trace of what might have once been perceived as subversion, or the ‘darkness’ he has often described – was taken by surprise. Instead, daylight flooded into an interior clad from floor to ceiling in, yes, beige. Silk scarves printed with the new logo were placed on every seat. Abramović crept in barely noticed, and elsewhere there was not a celebrity in sight. Tisci’s family was in attendance, for sure – his mother has never missed any of his shows. “For me the fact that it was so different was very modern,” he says by way of explanation. “I wanted to show respect for the house, for the work. Today, for Burberry, I am building a new language.”

And, of course, that language must be heard way beyond the runway, a fact well understood by this designer. In less than a year, Tisci has revamped Burberry’s flagship store on London’s Regent Street: an ultra-luxe, neutral interior is the order of the day, which will be rolled out gradually across the board. He persuaded none other than Westwood herself to design a capsule collection for the brand. Saville has masterminded the logo, Nick Knight’s lovely roses have made their way onto the walls of the store on Bond Street; Knight is also one of six photographers to shoot the new-season Burberry Campaign. The others include Danko Steiner, Hugo Comte, Colin Dodgson and Peter Langer. The mix of establishment and new names needs no explaining.

It is a measure of both Tisci’s open-mindedness and his confidence as a designer that he feels comfortable collaborating with young talent and, perhaps more so, names bigger than his own. “Vivienne is like a god to me,” he says, “and to so many people. She represents so much to so many people. When I first saw her work I was this young, gay boy in Italy looking at magazines. Femininity in a man is no problem, she taught me that. The elder designer was, he says, marginally thrown when he first approached her. “She said, ‘You are like the king of England now, why do you want to celebrate me?’ I answered, ‘I’m only here because of you, you were the one who opened my eyes.’” He is equally effusive when speaking of Messrs Saville and Knight. “The thread between them all is this country, my respect for this country,” he explains. “You remember the first time we met I said that to you. My respect for this country comes from my heart, my guts. And these people were the ones who opened all the doors for us. Today everything is fast – fast food, fast internet, fast everything – and we forget the amount of time spent building what now is the key to our success. These people wrote everything, the history of fashion, culture, style, politics. I thought, ‘I’m going to Burberry, Burberry is a British house, so why not celebrate all these amazingly talented British people?” And Burberry, too, is incredible, also very open, not scared of trying new things.”

The Burberry story begins with one Thomas Burberry, who in 1856, at the age of 21, set up as an outfitter in Basingstoke. He was joined by his sons – Thomas Newman Burberry and Arthur Michael Burberry in the late 1880s. In 1888, Burberry’s – as it was originally known – patented a method of processing yarn to ensure it was water repellent. It had actually been introduced by the company almost a decade before, but at this point it declared authorship, safe in the knowledge that this was a significant innovation, although perhaps unaware quite how significant. Around 1901, the company ran an open competition to create its logo: the result was the famous crest featuring an equestrian knight inspired by 13th- and 14th- century armour housed in the Wallace Collection in London (this collection, coincidentally, has also provided inspiration for Vivienne Westwood in the past); it was registered as a worldwide trademark in 1909. To cater to increased demand, Burberry, which already had a presence in London, opened a store on Haymarket in 1913. It would remain its flagship for almost a century. Today it is home to Dover Street Market. The famous trench coat, with its epaulettes, back vent, storm flaps and D-rings, dates back to the first world war and was developed for the British Army. Ernest Shackleton wore the design when he crossed the Antarctic. In 1920, Burberry became a Limited Liability Company, with its ordinary and preference stock quoted on the London Stock Exchange. The check came in during the 1920s, lining winter-weight overcoats. The company remained family-run until 1955, when Great Universal Stores Limited (GUS) took over. That same year, HM Queen Elizabeth II granted Burberry a royal warrant as a weatherproofer. By the mid-Sixties, its website claims, one in five coats exported from the UK carried its tag. In 1990, HRH the Prince of Wales awarded Burberry a further royal warrant, this time as an outfitter.

That Burberry’s rise has not been without setbacks is well known. By the mid-Seventies, and however popular, its name was primarily associated with tourists in search of a souvenir of unreconstructed – arguably, archaic – Englishness. The label was soon appropriated, by a rather different customer though – the dandified casual who, in a brilliant up-yours to the British class system, adopted Burberry, and the check in particular. By the turn of the millennium, over-licensing led to a flooded market: the check was ubiquitous. More damaging than that, it had become associated – not always fairly – with football hooliganism. In 2004 BBC news was among sources reporting that Burberry was on a list of labels banned from the premises in two pubs in Leicester – Stone Island, Aquascutum and Henri Lloyd were also cited.

In the meantime, when, in 1997, Rose Marie Bravo, the American-born former president of department store Saks, was appointed Burberry CEO, she immediately set about reining the Burberry check in. It was also Bravo who was the first to install a named designer – Roberto Menichetti, also Italian, incidentally – and who introduced the progressive, fashion-led Prorsum line. The name was derived from wording on the aforementioned knight’s crest. Prorsum is Latin, meaning ‘forward’ (the moniker was later dropped, but that spirit lives on). In 1999, Bravo employed Fabien Baron to redesign the logo, Mario Testino to enhance the brand’s image through print advertising and even changed the company name: Burberry’s became the rather less parochial Burberry. In 2001, Christopher Bailey, a softly spoken Yorkshire man, inspired by English style – from the spirit of Bloomsbury to Sixties London, and from David Hockney to Clarice Cliff – was named design director and, in 2002, Burberry was de-merged and became a public company, floated on the London Stock Exchange. In 2006, Angela Ahrendts, American-born and formerly executive vice president of Liz Claiborne and president of Donna Karan International, where she met Bailey, took over from Bravo as Burberry CEO. The Bailey-Ahrendts partnership was magical: they continued to expand the great British brand to the point where it positively dwarfed any potential rivals.

In its long history, Burberry has been responsible for many firsts. In 1934 it introduced a same-day delivery service and London’s streets witnessed the arrival of the Burberry’s vans. Under Bailey and Ahrendts, in 2010, Burberry became the first global brand to livestream a fashion show and, in 2016, the ‘see now buy now’ strategy had its roots here. Today, only select pieces are available under this initiative, exclusively on Instagram, WeChat and at London’s Regent Street store, and only for 24 hours following the show. It’s a smart move, one that serves to elevate any appeal.

For its legendary September issue, in 2012, American Vogue ran a feature celebrating under-45-year-old fashion designers, models and more, who were breathing new life into fashion. Bailey took centre stage; so, too, did Tisci. It is perhaps worth noting that the timeline of Bailey’s trajectory at Burberry was mirrored by Tisci’s at Givenchy. “That was great,” says Tisci, remembering the experience now. “That’s when I met him. Like me, he was very shy. He did an incredible job here, built this incredible empire.”

It is true that Bailey’s Burberry saw a transformation from tired status label beloved by tourists to massively lucrative fashion innovator and desirable designer name. After the spectacular decade of growth that followed its public listing in 2002, however, the success story became less certain. By the time Ahrendts moved to Apple in 2014, and Bailey was named Burberry CEO as well as creative director, the company’s losses became news. In 2017 Gobbetti arrived and Bailey was made president. He departed the company at the beginning of that year.

For his part, Tisci is looking back to long before his predecessor’s tenure to move the company forward.

“I’m very curious,” he says, “which I believe is important for any creative. So, when I arrived I became very good friends with this lady who works in the archive. I’m very into archive.” He doesn’t have a huge one of his own, he says, but does own a small selection of much-prized garments by a handful of designers. “I’ve got Versace, I’ve got Helmut, I’ve got Margiela, Rei Kawakubo, Yohji, some pieces of Armani. Armani was major – Armani is major. Anyway, this lady at Burberry, tall, blonde, beautiful, she was, like, ‘You can go inside – but we have to wear the gloves.’” Suitably garbed, Tisci sifted through the company’s lovingly amassed archives – material history; a king’s ransom of fashion treasures. “I found all these things and thought, ‘Oh, my god.’ Thomas Burberry was this man who was very well known in England, a powerful man, a man who dressed all these very strong men and women. There was the famous equestrian logo, this man fighting on a horse. For his family, and only for them, he designed ceramics and silverware engraved with that logo, nobody else knew about it. I think that’s so chic. We looked at that and then I found all these beautiful trenches, these scarf prints, classic jackets, black and white, with a big lapel, always very upscale. So I was thinking, OK, the gentlemen and the lady, I have to redefine the sophistication of really beautiful clothes made well. A lot of people have forgotten the importance of good quality, good cut. Of course, I also want Burberry to be immediate, inclusive and approachable.”

While Tisci’s vision of Burberry is certainly an optimistic one, he is aware of the difficulties facing both himself and Gobbetti and, indeed, Britain more broadly. “Of course we feel the pressure,” he says, “but we are together to fight for Burberry, to make it bigger, to understand its needs. Knowing how to fix it is our job. OK, everybody is talking about Brexit but what about America, what about France? What about Italy and Spain? There is a lot happening at the moment. And, yes, for the young generation especially, that scares me a little.”

Any fear aside, there’s no question that Burberry still wields considerable clout. Back to Christmas 2018 and 24 members of the Tisci family arrived in Paris for five days. “I felt like this year was really lucky for me,” he says. “I just joined Burberry, so I gave this big present to my sisters and their husbands, the kids, my mum. I brought them to Paris, you know, they left their problems at home. Burberry were super-nice, they organised for us to be at Notre Dame for midnight mass. I’m Catholic but I’m not practising. I pray but I don’t go to church much. But my mum does. It was beyond.”

In return, his family gave him a postbag stuffed with 44 letters from family and friends, one for each year of his life to date. The one he chooses to talk about, it almost goes without saying, is the letter from his mother. “My mum wrote to me that I am the prince of her life,” he says, “and that what makes her a queen, and happy forever, is that I am always going to be the child that she made – that, whatever happens, I will never change.”

In 2012, for an interview for this magazine, Tisci told me he felt that, although his father died when he was so young he cannot remember him, his father’s ghost has always been behind him – if anything, like that knight on that horse, driving him forward. Now he says: “I worked on that for a while. I wish there was another world where you could meet the people you didn’t have a chance to meet here. I wish I could meet my father just for one day, this man who everybody describes. The love that I was supposed to give to this man I gave to my mum and to my sisters. But he is not the ghost that sits behind me anymore. He sits next to me now. I’ve grown up. When I saw my mum at Christmas, I was so glad. I don’t know what’s going to happen tomorrow, and that is very hard, but in the end that is the beauty and the reality of life.”

I ask Riccardo Tisci what he would like his Burberry to represent. “Democracy, elegance, beauty and reality,” he says.

Hair: Gary Gill at Streeters. Make-up: Niamh Quinn at LGA Management using MAC. Model: Rianne Van Rompaey at Viva London. Casting: Noah Shelley at Streeters. Set design: Alice Kirkpatrick at Streeters. Digital tech: Simon Wellington. Photographic assistants: Peter Carter and Albi Gualtieri. Styling assistants: Laura Vartiainen and Hugo Lavin. Hair assistant: Tom Wright. Make-up assistant: Izzy Kennedy. Producers: Ciara Smith and Claire Green at Rep. Post-production: Hempstead May

This full story originally featured in the Spring/Summer 2019 issue of AnOther Magazine which will be on sale internationally from 14 February, 2019.